FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

During the late Sixties and early Seventies I seem to have developed the habit of reading, and writing up for my eyes only, a number of first mystery novels (either for an author or a byline) that for the most part I admired. Restricting myself to books by dead Americans that were first published under pseudonyms never seen before, I venture to cobble together my end-of-year column out of this ancient raw material.

The year before Davis Dresser (1904-1977) began using the name of Brett Halliday for his endlessly running Michael Shayne private eye series, he created a byline all but unknown today to chronicle the cases — all two of them — of Jerry Burke, an El Paso police administrator who favors brainwork over PI tactics.

In MUM’S THE WORD FOR MURDER, as by Asa Baker (Stokes, 1938), his adversary is a serial-killer who advertises in the local paper, daring Burke to stop him. After three apparently unconnected murders our hero comes up with a neat solution which is also found in at least three later crime novels much more familiar to readers than this one. (I’d be a toad if I revealed their titles or authors.)

Occasional realistic insights into poverty, anti-Mexican racism and literary amateurs make up for the ill-informed excursions into law and psychoanalysis. That the book Burke’s Watson is trying to write turns out to be the book we’re reading adds a Pirandelloesque fillip to a fine fast-moving unpretentious novel, which of course was reprinted as by Brett Halliday after that name had become a staple item in the genre.

Aaron Marc Stein (1906-1985) had been writing whodunits since 1935, first as George Bagby and then also under his own name. After wartime service as an Army cryptographer he launched a second pseudonym and a third series. THE CORPSE IN THE CORNER SALOON, as by Hampton Stone (Simon & Schuster, 1948), introduces Gibson and Mac, two investigators from the New York District Attorney’s office who get assigned to a case of apparent murder and suicide with grotesque sexual overtones.

Along with a raft of suspects and some deftly juggled criminal possibilities we are offered knowing evocations of the postwar clothing business, the old-style saloon milieu, and the postwar apartment shortage. The solution is so nobly complicated that I shrugged off the few loose strands of plot and the sniggering tone of the sex passages as minor annoyances.

Elizabeth Linington (1921-1988) wrote whodunits under her own name and several pseudonyms, each book being written in about two weeks. In CASE PENDING, as by Dell Shannon (Harper, 1960), she introduced Lt. Luis Mendoza, an arrogant, amorous, brilliantly intuitive LAPD Homicide detective who senses, and almost succeeds in tracking down, the link between two unconnected female corpses each with one eye mutilated.

Shannon interweaves the murder case with counterplots involving illegal adoption, the planned disposal of a blackmailer, a narcotics drop, and Mendoza’s pursuit of a bemused charm school instructor, but in every part of the book she irritates us by recording characters’ thoughts in the same monotonous ungrammatical shorthand they use when they speak.

On the plus side she has a gift for probing agonized minds (a 13-year-old boy who knows too much, a petty civil servant plotting the perfect murder), for adopting at least some of the values of the strict detective novel, and for presenting an explicit atheistic viewpoint without pretentiousness or propagandizing.

Emma Lathen, the joint pseudonym of Mary Jane Latsis (1927-1997) and Martha Henissart (1929- ), first appeared on the spine of BANKING ON DEATH (Macmillan, 1961), in which John Putnam Thatcher, vice-president of a prestigious Wall Street bank, has to elucidate a murder problem with ramifications in New York City, Buffalo, Boston and Washington.

The bank’s search for a missing trust fund beneficiary ends with the discovery that he’s been bludgeoned to death in the middle of a blizzard, and its duties as trustee require Thatcher to take a hand in the investigation.

The characters and writing are nothing special but there are fine evocations of Wall Street, Brahmin elitism, and the curious behavior of airports during snowstorms, and the deductive puzzle is neatly constructed.

It certainly wasn’t his first novel, but KINDS OF LOVE, KINDS OF DEATH, as by Tucker Coe (Random House, 1966), introduced a new byline and a new series character for prolific Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008).

A Syndicate boss who for obvious reasons can’t go to the police hires disgraced ex-cop Mitch Tobin to take a break from building a high wall around his house and find out who inside the “corporation†first seduced his lover and then murdered her.

The trail to the truth is basically psychological and unmarked by incidents of violence. Tobin guesses right far too often and the killer turns out to be a walk-on part, but Coe deals skillfully with a variety of failed relationships and unsentimentally with the insight that professional criminals are no different from other successful American businessmen.

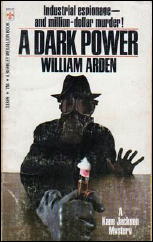

A DARK POWER, as by William Arden (Dodd Mead, 1968), was also not a debut novel except in the sense that, like KINDS OF LOVE, KINDS OF DEATH, it introduced a new byline and a new series character for its author, the equally prolific Dennis Lynds (1924-2005).

Industrial spy Kane Jackson, who seems to have been modeled on Lee Marvin’s screen persona, is hired by a New Jersey pharmaceutical combine to recover a missing sample of a drug potentially worth millions. The trail leads through mazes of inter-office love affairs and power struggles and several bodies, some naked and others dead, come into view along the way.

Arden meshes his counterplots with precision, draws several vivid characters trapped by their own ambitions in the jungle of high-level capitalism, and caps the story with a double surprise climax. The plot is resolved by clever guesswork but that’s the only weakness in this admirably tough-minded whodunit.

I’ve just discovered on the Web that half of Emma Lathen seems to be still alive, which means that I haven’t completely restricted myself to the dead. But I also discovered, while combing through comments I first typed up on my trusty Olympia Portable almost half a century ago, that I have enough material for January 2014 if the seasonal blahs continue to get me down.

Next time the subject will be American debut novels published under their authors’ own names. Meanwhile, until I cobble together my first column of the new year, happy holidays to all who may see this one.