Reviewed by Mike Tooney

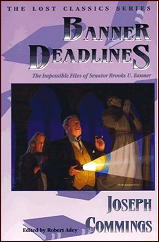

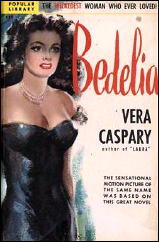

JOSEPH COMMINGS – Banner Deadlines: The Impossible Files of Senator Brooks U. Banner. Crippen & Landru: The Lost Classics Series, 2004. Short story collection; hardcover/trade paperback. Edited and introduced by Robert Adey; memoir by Edward D. Hoch.

Banner Deadlines is a fine collection of impossible crime short stories by one of the largely neglected masters of the form.

The back cover blurb explains further:

“Joseph Commings created one of the greatest investigators of locked rooms, impossible disappearances and other impossible crimes — the gargantuan, harrumphing Senator Brooks U. Banner. During his long career (Banner first appeared in the pulps in 1947), he investigated such crimes as murder at a seance where everyone is straight-jacketed together and linked by touching feet, a strange spectre causing death in the middle of a lake, a killing in a sealed glass case, and a murder by a sword which must have been wielded by a giant. The most extraordinary story of all is “The X Street Murders,” in which the victim is shot in a guarded room and the smoking-gun is delivered, a few seconds later, in a sealed envelope next door.”

The bibliography lists thirty-two stories featuring B.U.B., so fewer than half are here: 14/32 = 43.8 percent. One hopes that Crippen & Landru can get more published in the future.

An aside here about character credibility: In the days before ubiquitous television coverage, it seems possible that a person with Banner’s eccentricities of speech, dress, and behavior — not to mention that he does seem to spend an inordinate amount of time in pool halls handily defeating his opponents rather than working on the nation’s business — might indeed have enjoyed a long political career … but, then again, we are talking New York politics, right?

In his introduction, Robert Adey informs us: “In the early Banner adventures the cases brought to him, or over which he often seemed to stumble with an almost audible crash, were of the classic impossible crime variety, stuffed to the gills with locked room lore and traditional golden age ambiance.”

Furthermore, Commings’s “middle period stories contain puzzles which are just as ingenious as those Joe wrote for the pulps, and Banner is as keen in the chase and as stunning in his solutions as ever he’d been.”

Adey concludes, “If your tastes in detective fiction run to ingenious puzzles, locked room murders and atmospheric settings, then look no further. Allow us the pleasure of introducing a writer (one of the very few) whose flair and inventiveness in the construction of impossible crime problems place him fairly and squarely alongside those Golden Age maestros John Dickson Carr, Clayton Rawson and Hake Talbot, and a detective who, by virtue of his personality, eccentricity and ingenuity, stands comparison with Dr. Fell, Sir Henry Merrivale and the Great Merlini.”

Mike Grost also discusses Commings’s stories on his website here.

The Stories:

1. “Murder Under Glass” (1947). “I suppose you’ll tell me that you know a way that a murderer can go through solid glass without leaving a scratch on it.”

I’m working on it,” said Banner.

Comment: A rich man is murdered in a locked room made of glass (yes, you read that correctly). Characters speak in forties-style slang. The story is flecked with many short but effective descriptive passages that limn the characters’ personalities.

2. “Fingerprint Ghost” (1947). “If you wanna solve these murders, Archie, you gotta grab every opportunity.”

Comment: Murder right in the middle of a seance. Without wearing gloves, the killer uses the same knife that killed someone else and leaves no fingerprints. Like “Murder Under Glass,” the motive for the second killing is deeply embedded in the first crime.

3. “The Spectre on the Lake” (1947). “The way you tell it a phantom killer with a phantom gun crossed all that water without making a splash, got into the boat, shot both men dead, then went off the same way it came.”

Comment: Banner is an eyewitness to murder, but even he can’t positively identify the killer — and where did the weapon go? Perception — and the speed of sound — are everything.

4. “The Black Friar Murders” (1948). “As a general rule, wimmin ain’t the stabbing kind; they prefer poison and other mild things that corrode a fella’s carcass by small degrees. That’s why we call ’em the gentler sex.”

Comment: Banner gets invited to Thanksgiving dinner and is embroiled in a double murder. Quite atmospheric, and the story moves at a good clip.

5. “Ghost in the Gallery” (1949). Seeing the hanging corpse, Coyne crossed himself religiously and exclaimed, “Tis the divvil hisself!”

Banner scowled. “No. Just a poor sap with buck teeth.”

Comment: How do you kill Satan? Asians devised a method long ago, and it’s employed here. Banner’s solution is, well, elementary: “Every schoolboy knows that the angle of reflection is equal to the angle of incidence.”

6. “Death by Black Magic” (1948). “He was strangled,” repeated Banner grimly. “While I sat there watching….”

Comment: Murder in a haunted theater, but the “ghost” is real enough. This is a clever re-working of Othello, right down to the motives. Call it a “locked-theater problem.”

7. “Murderer’s Progress” (1960). “The bullet found in Wheaton’s head was fired from the gun left behind at the club. Then Wheaton was murdered with the gun while it was in my pocket!”

Lutz said wryly: “Have you got an aspirin?”

Comment: A game that goes fatally wrong, but Banner is up to the task. Envy and chess do not mix. As sometimes happens with Commings, two murders intertwine.

8. “Castanets, Canaries and Murder” (1962). “Not as much as a fly could have crawled across that space without being seen! How did a normal-sized murderer do it?”

Comment: The Invisible Man commits a murder, and dead canaries, a volatile movie star, carrier pigeons, and a lens all figure in it. Banner’s simple technical solution reveals hidden motives.

9. “The X Street Murders” (1962). McKitrick sighed. “Times are getting brutal for us investigators when all a murderer has to do is send his victim a gun by mail and it does the killing for him.”

Comment: Probably Commings’s most famous story. International espionage leads to two murders, the first one a marvel of intricacy and timing. An interesting variation on Christie’s “The Dream.” The author expands his catalogue of Banner descriptions, giving him “the physique of a performing bear” and comparing Banner to “an overgrown Huck Finn. Physically he was more than one man — he was a gang.”

10. “Hangman’s House” (1962). “If it’s suicide,” he said, “how did he cross thirty feet of floor without leaving any marks in the dust? How did he get the rope tied to that high chandelier when there’s nothing in the house to stand on? And if he jumped from the chandelier, he wouldn’t have been strangled — his neck would have been broken!”

“Brother,” said Banner, scowling, “you said a mouthful.”

Comment: Death, wearing a mask, vows revenge, and eleven years later exacts it. Banner is trapped with several others, one of them a murderer, who “will never forget the battering rain, the broken Mississippi levee, the thousand dancing candles, and the fifteen feet of rope.”

11. “The Giant’s Sword” (1963). Banner understood her. He understood people and he understood murder. Those were tears of frustration and anger. Whatever the reason for her grief, she wasn’t sorry to find Mark dead.

Comment: A most unusual murder method. One might say the victim was involved up to the hilt … and who knew that how much mileage a Volkswagen gets could prove so crucial to the solution of any crime?

12. “Stairway to Nowhere” (1979; with Edward D. Hoch). “Whuzzat? Oh, you mean a letter laying out in plain sight is overlooked.” Banner made clucking noises. “Nope. I never believed that theory. It’s a lotta bunk. If you’re hunting for a letter, you’ll examine every one you see. As for hidden bodies…”

Comment: A young woman disappears, as does a precious stone, and of course the two events dovetail. The crime here is something of a departure for Commings, as is the narrative viewpoint. The point-of-view character is not Banner but a young man emotionally involved with the missing lady. We are privy to his thoughts, not the senator’s.

13. “The Vampire in the Iron Mask” (1984). Banner paused… “I’ ll confess that this’s the first time I’ve found the solution to a murder by reading it in a magazine. Hah!”

Comment: This one, with its sepulchral atmosphere and intricate jiggery-pokery, is ALMOST as good as John Dickson Carr on one of his off days. Nevertheless, the plotting is first-rate and the setting, essential to character motivations, is well employed.

14. “The Whispering Gallery” (2004). “The weapon wasn’t held in the normal position at all. The guy with the gun must have been nine feet off the floor — and upside-down!”

“Police headquarters!… Send some boys over to Cagliostro Court to hunt for a man who’s missing in his own house.”

Comment: When a spiritualist debunker vanishes, a few people hovering around are highly motivated to see him stay vanished. A 3,000-year-old papyrus, a portrait with a bullet hole, a pack of tarot cards, a suave magician, an under-age bride, an albino policeman, and a body frozen in ice all figure in the mix.

Banner sorts it all out while practicing his own peculiar brand of magic. This is “the first publication — ever — of this story, one of only two previously unpublished Banner short stories of impossible crime.”