Mon 22 Jun 2009

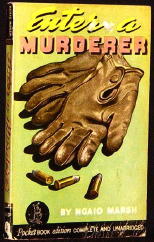

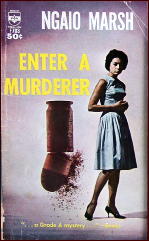

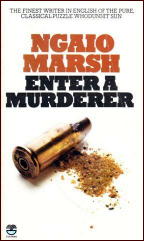

NGAIO MARSH – Enter a Murderer. Pocket 113, paperback reprint; 1st US printing, July 1941. Previously published in the UK by Geoffrey Bles, 1935. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and soft, including (and shown): Berkley F703, US, 1963; Fontana, UK, pb, 1968, 1983; St.Martin’s, US, pb, 1998.

I’m far from being an expert on Ngaio Marsh, so I can’t tell you what the circumstances were that Enter a Murderer was published for the first time in the US as a Pocket Book paperback, and not as a hardcover. But I imagine the story’s known, and perhaps someone reading this who can fill in the details will do so. (I’ve found nothing on the Internet so far that’s relevant.)

Enter a Murderer was only her second novel, which may be part of the explanation, and the first of five detective novels Marsh wrote which took place in the world of the theater, one of the loves of her own long life. (She was born in 1895, most reference sources say, and passed away in 1982.)

Dead is an actor, shot to death onstage, with dummy bullets having been replaced with live ones in the gun another actor used as part of the play, with the two directly facing each other.

That the dead man was a blackmailer (as it is soon discovered), a womanizer and a thwarted lover (as was well known), plus various and sundry other flaws, gives a motive to everyone on or near the stage. A blackout to open the final act gave everyone an opportunity.

The investigation that results, carried out by Chief-Det. Inspector Alleyn (primarily) and his assistant on the case, Inspector Fox (secondarily), is both aided and abetted by news journalist Nigel Bathgate, a friend of Alleyn whom he invited to the play, which they watched together to its final and deadly conclusion.

It’s not always an easy relationship. Bathgate is willing to let Alleyn censor his reporting, but he’s not always inclined to ask potentially embarrassing questions of friends who happen to be under suspicion.

Sometimes the investigation (from the reader’s point of view) is told with Alleyn as the protagonist, and sometimes it’s from Bathgate’s point of view. It’s a combination that Marsh may have thought she needed to present the story more efficiently from several angles, but it’s not as smoothly done as I thought it might have.

The action in and around the stage is clearly delineated, though, many times over, even to a final reconstruction of the crime at the end – always a welcome touch in classical detective fiction, resembling as it does the “isolated country house” theme in certainly the most essential way.

But the business of the blackmail never seems to be addressed directly. It’s as if it were shunted to the side, not abruptly, but Marsh never seems to tackle it head on, leaving the motive for the killing murky, while a full spotlight is shed upon the setting. (At times you can all but smell the greasepaint.)

Upon finishing the book I was more than satisfied with the solution – nicely done – but I’m still uneasy about there being some loose ends that I didn’t (and still don’t) feel as though they were wrapped up properly enough.

This has nothing to do with the actual solution, mind you. I like the ending well enough that I haven’t felt the need to poke around into that pile of red herrings stacked over there in the corner (figuratively speaking). It’s just the sense that I ought to, in order to give you an honest report.

But I’ve decided not to – go back through the book and poke around, that is – and what you’ve just read is as honest as it’s going to get.

Do I recommend the book? Yes, I do, but I assume you’ve already read and recognized all of the caveats (both major and minor) for what they’re worth as well.