A Review by MICHAEL GROST:

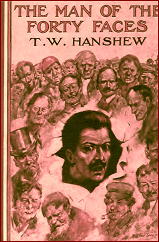

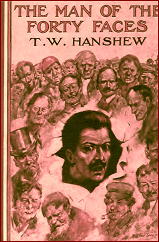

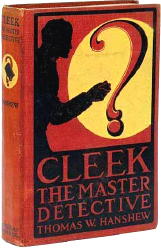

THOMAS W. HANSHEW – The Man of the Forty Faces. Cassell, UK, hardcover, 1910. US title: Cleek, the Master Detective. Doubleday Page, 1918.

Sleuth Hamilton Cleek made his debut in the short story collection, The Man of the Forty Faces. The Cleek mysteries by the Hanshews [Mary E. Hanshew later collaborated with her husband in writing them], which often feature impossible crimes, were favorite childhood reading of John Dickson Carr.

Ellery Queen‘s somewhat satiric comments on the tales focused on the campier aspects of the Cleek saga, with the detective Hamilton Cleek being a Balkan Prince caught up in Ruritanian romance.

One that I have read for the first time, “The Riddle of the 5:28”, I find far more of a straightforward mystery tale than I had imagined. It is not at all campy in tone, the Prince works closely and normally with Scotland Yard, and a fair play impossible crime story is spun out, entertainingly if somewhat implausibly in solution.

There are signs of trying to appeal to a (male) juvenile audience in the stories: the Prince employs a Cockney lad (19 years old) as an assistant, he being a character with whom boys might identify; the prose tries to create a thrilling tone, complete with dramatic climaxes; and there is a great deal of attention paid to trains, automobiles and other machinery, something that boys of all ages love. By contrast there is a great deal of grown up romance, including a villainous character who engages in adulterous affairs.

The tone of the story over all matches that of Arthur B. Reeve‘s Craig Kennedy stories to come, with its stalwart, highly intelligent hero; a cast of characters involved in the corrupter aspects of the era’s high life and all under suspicion, with the characters all assembled at the end for the revelation of the guilty party by the detective; the emphasis on dramatic writing; the focus on technology and machinery; and a setting more of public life than of pure domesticity.

The Man of the Forty Faces appeared in book form in 1910, however, the year before Reeve started writing his Craig Kennedy tales in 1911.

Some of the other tales in The Man of the Forty Faces also involve scientific mysteries. “The Riddle of the Ninth Finger”, “The Lion’s Smile”, and “The Divided House” are all about mysterious illnesses or afflictions, that seem to have no known cause. Cleek eventually provides medical, science-based explanations for the afflictions.

“The Divided House” is the best of these, the one where the solution is cleverest, and also most plausible. “The Riddle of the Ninth Finger” is the poorest, with the circus melodrama “The Lion’s Smile” somewhere in the middle. These stories perhaps influenced Agatha Christie, for example, in “The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb” and “The Tragedy at Marsden Manor”, in Poirot Investigates.

“The Riddle of the Rainbow Pearl” has a full-fledged background of Ruritanian romance. It is well done and entertaining escapist storytelling. It combines this with a mystery plot about a search for a hidden object, in the tradition of Edgar Allan Poe‘s “The Purloined Letter” (1845). Some of the intrigue also reminds one of Doyle’s “A Scandal in Bohemia” (1891). The mystery solution is more science-oriented than either Poe or Doyle, however, in keeping with the scientific detection aspect of Hanshew.

Other of the tales also look for hidden objects: “The Riddle of the Sacred Son”, “The Riddle of the Siva Stones”. “The Riddle of the Sacred Son” has some good storytelling, as well as a clever solution. Just as “The Riddle of the Rainbow Pearl” has a delirious melodrama in a Balkan kingdom, so does “The Riddle of the Sacred Son” invoke an Oriental extravaganza.

Unfortunately, the tale’s complete lack of realism about Asian countries, and its nonsensical depiction of Asian religion, are in a mode that has become dated, and are now likely to offend. Hanshew went to great efforts to depict the Asian priest in the tale as a man of dignity, intelligence and high moral character.

He was clearly trying to write a story that would be non-racist, and which would form a contrast to the racist tales of Oriental villains that were then so popular. This is all to his credit. However, non-realism about Balkan kingdoms, as in “The Riddle of the Rainbow Pearl”, is now just considered campy fun. Non-realism about Asia, a place with an ugly history of being exploited by European Colonialism, is still a matter of concern.

Two tales involve disappearances. Such a vanishing inevitably brings up that favorite question of R. Austin Freeman: the disposal of the body. Both “The Caliph’s Daughter” and “The Wizard’s Belt” have some original ideas on the subject, in their solutions.

Unfortunately, neither is really gripping as a work of storytelling. Considering their early date, one wonders if Freeman influenced Hanshew, or Hanshew influenced Freeman, or whether their common interest in the disposal of the body was merely part of the zeitgeist. Elements of “The Caliph’s Daughter” anticipate such Freeman novels as The Eye of Osiris (1911) and The Jacob Street Mystery (1941).

“The Problem of the Red Crawl” is a thriller, without real elements of mystery. It exploits Cleek’s ability to impersonate seemingly any other person. Cleek anticipates later heroes with similar gifts, such as Ellery Queen’s detective Drury Lane (1932-1933), and 1940’s comic book characters such as The King and The Chameleon.

The real mystery stories in The Man of the Forty Faces do not use this ability. Instead, when Cleek disguises himself in these tales, it is as an imaginary person, a new made-up persona. “The Problem of the Red Crawl” is a fairly entertaining melodrama. The red crawl of the title is vivid.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. This review has been reprinted from Mike’s website, A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection, which is exactly what the title says. I was prompted in doing so because of David Vineyard’s recent post which also mentioned both Hanshew and Freeman.

The links in the review above point back to Mike’s commentary on each of the authors so designated. Go visit his site at your own risk. If you’re a fan of traditional detective stories, you may stay a while.