Mon 23 Mar 2009

Archived Review: ELIZABETH GUNN – Crazy Eights.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Reviews[2] Comments

ELIZABETH GUNN – Crazy Eights.

Worldwide, paperback reprint; March 2006. Hardcover edition: Forge, February 2005.

This isn’t the first appearance of Jake Hines, whose case this is, by any means — and I’ll get back to that in a minute — but this is the first one that he’s has been involved in that I’ve happened to read. So before starting the review itself, I’ll begin with some small bits (or bytes) of information.

Hines, who tells the story, is the chief of detectives in Rutherford, Minnesota, and the woman who’s living with him is Trudy Hanson, a forensic scientist at the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension in St. Paul, about eighty miles away. They must have gotten together earlier in the series, since the story begins with them well-ensconced on their farm, located halfway between their two jobs.

They get along well, and as you probably have realized without my telling you, a certain amount of shop talk takes place at home – or in other words, all the crime news in the area seemingly filters one way or another through one of them. FOOTNOTE 1.

Here’s a long quote to help further this introduction along, from page 10, which is about where the story itself begins, as the reader finds Jake being woken up at four in the morning:

And as I promised, here are the earlier entries in the series:

Triple Play. Walker, hc, September 1997. Dell, pb, November 1998.

Par Four. Walker, hc, December 1998. Dell, pb, December 2000.

Five Card Stud. Walker, hc, May 2000. Worldwide, pb, July 2001.

Six-Pound Walleye. Walker, hc, June 2001. Worldwide, pb, July 2002.

Seventh-Inning Stretch. Walker, hc, June 2002. Worldwide, pb, June 2003.

“Too Many Santas” A short novel (or long novella) contained in How Still We See Thee Lie, no editor stated, Worldwide, November 2002.

Crazy Eights. Forge, hc, February 2005. Worldwide, pb, March 2006.

Some questions remain to be answered. For example, what happened to the “first two” books in the series? Will they ever be told?

Also notice the short gap in continuity and the save by Forge Books when Walker canceled all of their genre fiction categories, I believe, including mysteries, or is there more of a story there? Gunn’s paperback publisher at the time, Worldwide, an imprint of Harlequin, must have helped the cause in the interim, publishing a non-numerical shorter entry in the series as they did.

But in any case, there is some history behind the characters, and when you come in late, you have to get used to dealing with it really quickly. But the author does it right, and the paragraph quoted above is a good part of what does it.

What is unusual –- I can’t think of another instance –- is that the story that follows –- the one about the case that Jake is called out on (at four in the morning) –- jumps right from Chapter One and into Chapter Two, which begins with the courtroom trial of the second of two small-time hoodlums who kidnapped and killed Shelley Gleason in Chapter One. Time elapsed: a year and a half later.

What happened in the meantime? In a very interesting way of telling the story, Gunn lets the reader sort it all out through the ensuing testimony. This is not all that is unique. When the trial is over and the defendant is found –- well, no, I can’t tell you that, but what I can tell you that there is a confrontation between the accused Benny Niemeyer and one of the prosecuting attorneys that has never happened in a work of fiction before, ever. FOOTNOTE 2.

This is on page 102, and *whew* there are over 160 pages to go. Perhaps it suffices to say that medium-sized towns like Rutherford MN have a lot of secrets on both sides of the track, and on occasion there are oodles of opportunity for crossover. Most of the rest of the book plays itself out with relatively straight-forward plotting and story-telling. Unless, of course, you consider a relatively innocent skateboard as (also) being a relatively uncommon clue in the annals of detective fiction, as I do.

FOOTNOTE 1. I was curious about Rutherford, so I looked up the town on Google. No such place. The first two references to Rutherford MN were directly related to Elizabeth Gunn’s series of books, which may give Ms. Gunn her own two moments of fame right then and there (or here and now).

FOOTNOTE 2. What I said I couldn’t tell you is the first thing out of the mouth of the blurb-writer who’s responsible for describing the book on the back cover. Do I feel dumb, or what?

[UPDATE] 03-20-09. Since this review was written, there has been one more book in the Jake Hines series, perhaps the last?

McCafferty’s Nine. Severn House, hc, 2007; trade pb, 2008.

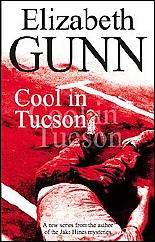

And the author has started a new series, one with Tucson police detective Sarah Burke as the primary protagonist:

Cool in Tucson. Severn House, hc & trade pb, 2008.

New River Blues. Severn House, hc & trade pb, 2009.