Part One of this ongoing discussion appeared

here. This comment left by David Vineyard earlier today was #17 for that post, and I’ve deemed it substantial enough to appear on its own.

I’ll continue to be occupied with a host of other matters this week and next, so images will be added later, as I can get to them. For now it’s the text that matters, and from this point on, David has the floor. — Steve

I’m going to go out on a limb here and say why I don’t think some films embraced as noir really belong there, then saw it off behind me by trying to define what noir is. But first the films that I don’t think really are noir despite having noir elements.

I’ve already explained why I don’t think The Maltese Falcon is noir — Spade is hardly alienated, doomed, obsessed or the victim of mysterious forces. He’s in control of himself and the situation, and the closest he comes to a touch of noir is a pang of regret at sending Brigid up the river for killing Archer. The only bad nights Spade is going to have is getting Miles Archer’s widow off his neck.

Laura is a bit more problematic, because the sleuth is briefly obsessed, but in the end he isn’t a noir protagonist either. Clifton Webb’s villain is alienated and obsessed, but in noir it’s the hero and not the villain that counts.

I Wake Up Screaming would be noir if Laird Cregar’s cop was the hero, but the hero and heroine are PR man Victor Mature and showgirl Betty Grable, and if you remove the murder plot, the two would be perfectly served in a musical (in fact, they were).

Johnny Eager is a slick MGM take on a Warner’s gangster movie, but again the hero, Robert Taylor isn’t a noir hero (his buddy Van Heflin is though, but that doesn’t count). There is nothing in Johnny Eager’s character different than the general run of gangsters in a hundred similar films.

All of these films use the shadows and high contrast lighting of noir, but then so does the swashbuckler The Sea Hawk. They all have noir elements, but they lack the core elements that define noir. For that matter I would put Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt as only borderline noir (Teresa Wright is neither alienated, obsessed, nor beset by mysterious forces — she’s Nancy Drew caught in an adult mystery).

Shanghai Gesture is an old fashioned German Expressionist melodrama, and not a noir though a contributor to the genre. An argument can be made however for You Only Live Once, Street of Chance, Mask of Dimitrios, The Stranger on the Third Floor, and Journey Into Fear.

I’ll give them their points, and only point out that two of them are spy films and by that nature share elements with noir, and the two spy films are directed by Noir director Jean Negulesco and Orson Welles (though credited to Norman Foster). The elements of distrust, paranoia, and betrayal common to most spy films are noirish to begin with.

But then what is noir? We’ve beat around the noir bush and come up with some general ideas — as Walker Martin points out it is a style — but it isn’t just a style, or every moody horror film would be noir, so I’m going to try to break down some key elements that I think define noir.

First of all noir is defined by the protagonist, and the noir protagonist has some distinct characteristics. As often as not he’s a veteran who is having a tough time adjusting to the peace time world, but veteran or not he is always alienated in some way.

In noir this means he is lost in a darkness he carries inside of him, but which is expressed by the world outside of him. He is inevitably an urban figure, usually in an urban setting (but even in a rural setting — On Dangerous Ground, Un roi sans divertissement — the hero is an urban figure).

Above all he is opposed by a “mysterious force,” a situation or antagonist beyond his control which leaves him with a sense of fear, powerlessness, and isolation. He is faced with forces of chaos he can’t control and sometimes is even attracted to. The noir hero is at the mercy of forces he can’t control and can only hope to survive.

The second factor key to most — but not all — noir is obsession. The noir protagonist is invariably obsessed — with the truth, revenge, a woman, power, money, or an impossible dream. He carries that obsession to the point it nearly (or does) destroy him (these definitions all define the female protagonists of noir as well).

He is set apart by the obsession, and though he recognises the power it has over him he can’t escape. That inability to escape from one’s fate is another key element of noir. You can run from everything but yourself.

Noir style is also important. High contrast lighting gives objects a certain sinister feel. Traffic lights, street lights, rain-soaked streets, narrow alleys, dark stairwells in cheap apartments, abandoned buildings, fire escapes, the sewers beneath the city, darkened warehouses — all these places and things take on a character of their own.

The freighter where the final scene of Anthony Mann’s T-Men takes place, the bridge girders Arturo De Cordova flees onto in The Naked City, the tunnels beneath Union Station, the sewers of LA in He Walked by Night, the refineries in White Heat and Follow Me Quietly, the merry-go-round in Strangers on a Train, the office stairwell in Mirage‘s blackout, the bleak snowbound countryside in On Dangerous Ground and Murder Is My Beat, the baseball stadium in Experiment in Terror, the inner works of the Big Clock, the elaborate garden in Night Has 1000 Eyes, the claustrophobic corridors of the train in Narrow Margin, and the carnival fireworks of The Bribe are all as much characters in the film as any human. They are familiar and alien at the same time.

In their book Film Noir (Overlook Press, 1979), Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward write that Noir “consistently evokes the dark side of the American persona … a stylised vision of itself, a true cultural reflection of the mental dysfunction of a nation uncertain of transition.” They put the classical noir period between the end of WWII and the end of the Korean Conflict when the country is in transition from the war and the influx of returning veterans adjusting to civilian life — and setting off the baby boom.

Among the other staples of noir is the femme fatale. She is hardly new to literature (lest we forget Delilah or Madame De Winter), but the noir protagonist is uniquely unable to resist or recognise her (Sam Spade on the other hand, not only recognises her, but plays her and ultimately disposes of her).

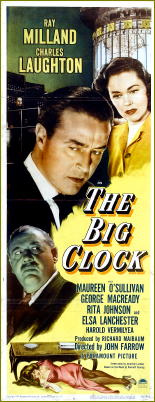

To this sexual confusion is added an atmosphere of violence, paranoia, and threat. The hero is vulnerable and beset by grotesque characters that seem to come out of a horror film at times (in The Big Clock Charles Laughton is shot in closeup with a wide angle lens that further distorts his already magnificently ugly features). Many of the characters in noir would be at home in Paris Grand Guignol or Dicken’s novels.

Certain visual cues are important, high contrast lighting, shadows, disorienting angles, and the sudden threat of ordinary and even benign objects (in The Big Combo policeman Cornell Wilde is tortured by gangster Richard Conte with Brian Donlevy’s hearing aid). There is often a dream scene or a brief use of nightmare imagery, and frequently flashbacks that disrupt the narrative flow.

Along with the grotesque there are frequently suggestions of perversion — twisted sexuality just beneath the surface (in The Glass Key William Bendix’s Jeff virtually seduces Alan Ladd as he beats him, calling him “Baby”), Clifton Webb’s aesthete villain in The Dark Corner is either asexual or homosexual (homosexuality is inevitably presented as perversion in noir, but then so are most forms of heterosexuality).

The femme fatale in noir often seems to feed on and desire humiliation, and take a perverse pleasure in destruction like some strange incarnation of Kali or a Dionysian bacchanalia. It’s the old fear of female sexuality sharpened to a knife point.

The films are also marked by a sort of hyper acuity of the senses. Blacks are deeper, light areas brighter, edges more defined. In Phantom Lady when Elisha Cook Jr.s’ hophead drummer plays a solo it rises in crescendo into a near sexual climax. The interior of the big clock in The Big Clock looks like an alien spaceship. When Philip Marlowe falls into a black pool it swallows him and the viewer. The sharpness of edges in noir is one of the most important visual cues, one that becomes startlingly clear if seen on the big screen or on today’s HDTV’s with superior digital DVD or Blu Ray.

One last key element of many noir’s is narration. This can vary from the poetic hardboiled voice of Dick Powell’s Marlowe, Tom Brown’s doomed drifter, Chill Wills’ embodiment of Chicago in The City That Never Sleeps, or the dry baritone of Reed Hadley emotionlessly keeping us informed in the docu-noirs.

The narration is at its most effective in Sunset Boulevard when William Holden’s Joe narrates from his own murder scene. The narration allows us inside the head of characters in ways that dialogue can’t always. At the same time it reminds us we are all to some extent trapped in our own mind.

Not all of these elements are in every noir film, but enough of them predominate that they can be used to define the genre. There are always going to be films that are on the edge one way or another, and because of its nature I’m not sure noir can be defined precisely, but I’ll name seven key factors I think are vital.

1. Alienation.

2. Obsession

3. Visual Style

4. Destructive Sexuality

5. Grotesque characters

6. Narration

7. Stylized violence

Any four of those elements in one film and I think you have to grant it is noir, but three or less is problematic, and unless the psychological elements apply to the protagonist it probably isn’t noir.

And one last rule that will certainly be controversial — I don’t think you can really claim it is the Hollywood noir school if it is made before at least 1944, though it may be an immediate precursor of the genre (This Gun For Hire, Street of Chance, Journey Into Fear, Citizen Kane …).

I don’t think true noir exists without the catalyst of WWII and the returning veteran. Like the atomic genie, the war let loose a new twist in the American psyche as defined as Hemingway’s Lost Generation, and it is out of that and many tropes of popular literature and film that film noir arises, as clearly as the detective story comes into focus with Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes in ways it had not in the period from 1841 in Poe’s Rue Morgue until Holmes.

Many of the elements are there, but until the right moment they don’t become a distinct form.

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.