EDGAR WALLACE AT MERTON PARK

by Tise Vahimagi.

Afforded only a footling footnote in the history of British cinema, the Merton Park Edgar Wallace films remain consistently enjoyable as a series of hectic penny dreadfuls, at times complication piles upon complication bewilderingly, but more often moving at a cracking pace. While not quite film noir, in true observation of the term, there is a grimy pleasure to be derived from these modest little dramas.

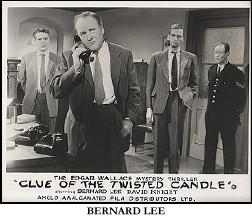

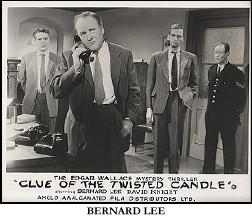

Though never entirely convincing, they do unfold with a quiet slickness, arousing curiosity, delivering a few plot-twist surprises, and displaying some competent performances. A pre-Bond Bernard Lee, for instance, shows up a few times as various Detective Superintendent types; and Hazel Court amuses herself as a very well-bred private eye in The Man Who Was Nobody (1960).

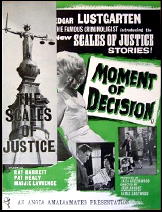

Merton Park Studios (1937 to 1967) was the prolific producer of the Edgar Wallace series of supporting features (released between 1960 and 1964), along with the similar Scotland Yard (1953-1961) and Scales of Justice (1962-1967) films.

This was the low-budget production world of a film-per-week schedule (up to 14 camera set-ups a day); the first Edgar Wallace film was released in November 1960 (in the UK); the 25th Wallace film went into production at the end of September 1962.

In 1960, Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy, managing directors of distributor Anglo Amalgamated (UK), acquired the film rights for world-wide distribution of the entire Wallace library. They gave the go-ahead to Merton producer Jack Greenwood (1919-2004) to make a �series’ of supporting features for their distribution circuit.

In his professional capacity, Greenwood may have been Britain’s Sam Katzman, keeping a firm hand on the purse strings and pushing cast and crew to the last penny’s worth. He was, thankfully, also producer of the realistic 1960 prison drama The Criminal (US: The Concrete Jungle), starring Stanley Baker, and, in 1967, became production controller on The Avengers series at ABPC Elstree Studios.

Merton Park Studios was based in a modest-size house in suburban south west London, employing a roll-call of British character actors, hired by-the-day (as well as some affordable European players), and utilizing the neighbouring streets and sites as economic locations.

Some 40 titles make up the run of Edgar Wallace films. Less than half were based on actual Wallace material, the rest consisting of original screenplays to supplement a saleable package under the Wallace introductory logo (a revolving bust of Wallace, sometimes tinted a bilious green, accompanied by twangy electric guitar music performed by The Shadows).

A list of the Edgar Wallace/Merton Park titles will follow this overview.

By the time the Wallace films started, Greenwood/Merton Park had already been producing a similar series of supporting programmers. Introduced by grim-faced journalist/criminologist Edgar Lustgarten (1907-1978) since 1953, the Scotland Yard series (produced until 1961) were sufficiently suspenseful police investigation dramas based on real-life cases (apparently).

The early films directed by Ken Hughes are interesting for their imaginative application of catchpenny production values. Since all the Wallace stories were updated to the 1960s, there is little to distinguish between the series; except perhaps that the Scotland Yard films often featured deadpan Russell Napier as the coldly businesslike detective.

Following on, the Scales of Justice series (released 1962 to 1967) added to Anglo’s distribution titles between Wallace productions. Lustgarten, again, introduced dark and dire case-file stories of crime-and-comeuppance with his customary solemnity.

The basic form and content of the three series was pretty much interchangeable, leading the later TV packages to often confuse the films’ origins. The UK experience remains that these films were originally produced for the cinema screen.

The US viewing experience, via TV presentations, has led many to believe that they were made for television. The Wallace films went to US TV as The Edgar Wallace Mystery Hour (or Theatre), usually trimmed to accommodate an hour slot (syndicated from c.1963).

Scotland Yard (39 x 26-34 min. films) was syndicated from 1955, and later shown via ABC from 1957 to 1958 in half-hour form. Scales of Justice (originally 13 x 26-33 min. films) probably supplemented the above TV packages.

Edgar Wallace films:

(The following are presented in order of production date, by year). I have also tried to give story source, where known.)

1960:

1. The Clue of the Twisted Candle. Bernard Lee, David Knight, Frances De Wolff. Screenplay: Philip Mackie; from the 1916 novel. Director: Allan Davis.

2. Marriage of Convenience. John Cairney, Harry H. Corbett, Jennifer Daniel. Scr: Robert Stewart; based on The Three Oak Mystery (1924). Dir: Clive Donner. [Follow the link for the first eight minutes on YouTube.]

3. The Man Who Was Nobody. Hazel Court, John Crawford, Lisa Daniely. Scr: James Eastwood; from the 1927 novel. Dir: Montgomery Tully.

4. The Malpas Mystery. Maureen Swanson, Allan Cuthbertson, Geoffrey Keene. Scr: Paul Tabori, Gordon Wellesley; based on The Face in the Night (1924). Dir: Sidney Hayers. [See NOTES below.]

5. The Clue of the New Pin. Paul Daneman, Bernard Archard, James Villiers. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1923 novel. Dir: Allan Davis.

1961:

6. The Fourth Square. Conrad Phillips, Natasha Parry, Delphi Lawrence. Scr: James Eastwood; based on Four Square Jane (1929). Dir: Allan Davis.

7. Partners in Crime. Bernard Lee, John Van Eyssen, Moira Redmond. Scr: Robert Stewart; based on The Man Who Knew (1918). Dir: Peter Duffell.

8. The Clue of the Silver Key. Bernard Lee, Lyndon Brook, Finlay Currie. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1930 novel (aka The Silver Key). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

9. Attempt To Kill. Derek Farr, Tony Wright, Richard Pearson. Scr: Richard Harris; based on the short story The Lone House Mystery (1929). Dir: Royston Morley.

10. The Man at the Carlton Tower. Maxine Audley, Lee Montague, Allan Cuthbertson. Scr: Philip Mackie; based on The Man at the Carlton (1931). Dir: Robert Tronson.

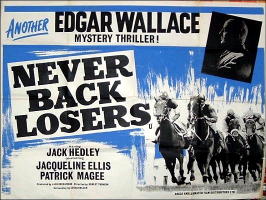

11. Never Back Losers. Jack Hedley, Jacqueline Ellis, Patrick Magee. Scr: Lukas Heller; based on The Green Ribbon (1929). Dir: Robert Tronson.

12. The Sinister Man. John Bentley, Patrick Allen, Jacqueline Ellis. Scr: Robert Stewart; from the 1924 novel. Dir: Clive Donner.

13. Man Detained. Bernard Archard, Elvi Hale, Paul Stassino. Scr: Richard Harris; based on A Debt Discharged (1916). Dir: Robert Tronson.

14. Backfire. Alfred Burke, Zena Marshall, Oliver Johnston. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: Paul Almond.

1962:

15. Candidate for Murder. Michael Gough, Erika Remberg, Hans Borsody. Scr: Lukas Heller; based on “The Best Laid Plans of a Man in Love” [publication date?]. Dir: David Villiers.

16. Flat Two. John Le Mesurier, Jack Watling, Barry Keegan. Scr: Lindsay Galloway; based Flat 2 (1924). Dir: Alan Cooke.

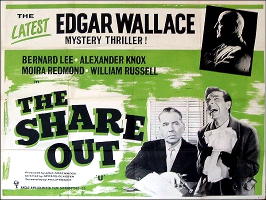

17. The Share Out. Bernard Lee, Alexander Knox, Moira Redmond. Scr: Philip Mackie; based on Jack o’ Judgment (1920). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

18. Time to Remember. Harry H. Corbett, Yvonne Monlaur, Robert Rietty. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on The Man Who Bought London (1915). Dir: Charles Jarrott.

19. Number Six. Nadja Regin, Ivan Desny, Brian Bedford. Scr: Philip Mackie; from the 1922 novel. Dir: Robert Tronson.

20. Solo for Sparrow. Anthony Newlands, Glyn Houston, Nadja Regin. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on The Gunner (1928; aka Gunman’s Bluff). Dir: Gordon Flemyng.

21. Death Trap. Albert Lieven, Barbara Shelley, John Meillon. Scr: John Roddick. Dir: John Moxey.

22. Playback. Margit Saad, Barry Foster, Victor Platt. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: Quentin Lawrence.

23. Locker Sixty-Nine. Eddie Byrne, Paul Daneman, Walter Brown. Scr: Richard Harris. Dir: Norman Harrison.

24. The Set Up. Maurice Denham, John Carson, Maria Corvin. Scr: Roger Marshall. Dir: Gerard Glaister.

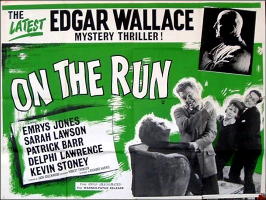

25. On the Run. Emrys Jones, Sarah Lawson, Patrick Barr. Scr: Richard Harris. Dir: Robert Tronson.

1963:

26. Incident at Midnight. Anton Diffring, William Sylvester, Justine Lord. Scr: Arthur La Bern. Dir: Norman Harrison.

27. Return to Sender. Nigel Davenport, Yvonne Romain, Geoffrey Keen. Scr: John Roddick. Dir: Gordon Hales.

28. Ricochet. Maxine Audley, Richard Leech, Alex Scott. Scr: Roger Marshall, based on The Angel of Terror (1922, aka The Destroying Angel). Dir: John Moxey.

29. The �20,000 Kiss. Dawn Addams, Michael Goodliffe, Richard Thorp. Scr: Philip Mackie. Dir: John Moxey.

30. The Double. Jeannette Sterke, Alan MacNaughtan, Robert Brown. Scr: Lindsay Galloway; from the 1928 novel. Dir: Lionel Harris.

31. The Partner. Yoko Tani, Guy Doleman, Ewan Roberts. Scr: John Roddick; based on A Million Dollar Story (1926). Dir: Gerard Glaister.

32. To Have and To Hold. Ray Barrett, Katharine Blake, Nigel Stock. Scr: John Sansom; from the short story “The Breaking Point” (1927) collected in Lieutenant Bones (1918). Dir: Herbert Wise.

33. The Rivals. Jack Gwillim, Erica Rogers, Brian Smith. Scr: John Roddick; based on the short story collection Elegant Edward (1928). Dir: Max Varnel.

34. Five To One. Lee Montague, Ingrid Hafner, John Thaw. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on The Thief in the Night (1928). Dir: Gordon Flemyng.

35. Accidental Death. John Carson, Jacqueline Ellis, Derrick Sherwin. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on the novel Jack O’Judgment (1920). Dir: Geoffrey Nethercott.

36. Downfall. Maurice Denham, Nadja Regin, T.P. McKenna. Scr: Robert Stewart. Dir: John Moxey.

1964:

37. The Verdict. Cec Linder, Zena Marshall, Nigel Davenport. Scr: Arthur La Bern; based on The Big Four (1929). Dir: David Eady.

38. We Shall See. Maurice Kaufmann, Faith Brook, Alec Mango. Scr: Donal Giltinan; based on We Shall See! (1926; aka The Gaol Breaker). Dir: Quentin Lawrence.

39. Who Was Maddox?. Bernard Lee, Jack Watling, Suzanne Lloyd. Scr: Roger Marshall; based on the short story “The Undisclosed Client” (1926) collected in Forty-Eight Short Stories (1929). Dir: Geoffrey Nethercott.

40. Face of a Stranger. Jeremy Kemp, Bernard Archard, Rosemary Leach. Scr: John Sansom. Dir: John Moxey.

NOTES: Many sources say that there are 47 films in the series, including the Classic TV Archive. I have looked at the latter’s file and decided not to follow their lead because they combined two companies (Merton and Independent Artists). My list includes only those produced by Merton Park.

When the films in the British Edgar Wallace series were shown as part of a syndicated televised series in the US, the package was very likely boosted to 47 (or even more) with other, non-related titles. The EW title logo can be edited on to the opening of anything that looks similar (or fits the programme slot).

A good example is NBC’s Kraft Mystery Theatre (1961-63), where the first season (June-Sept, 1961) consisted of even more British B-movies re-edited for a one-hour TV slot. See this page for more details. One film I can remember (shown as a part of this group) is the non-mystery House of Mystery, which is actually a very effective, rather spooky supernatural/ghost story.

In the instance of the Merton Park-Edgar Wallace series, since 47 is often given as the number of films, I’ll use the Classic TV Archive list to describe the differences.

Independent Artists, set up by producer Julian Wintle, started in 1948; he was joined by Leslie Parkyn in 1958, locating the company at Beaconsfield Studios, England. Their only connection with Merton, apparently, was the distributor Anglo Amalgamated, who handled films for both companies. (Perhaps it was Anglo who made the sale of packages to US television?)

The Man in the Back Seat (1961), which was the subject of the original enquiry, was an IA film, distributed by Anglo (released in the UK in August 1961). British trade journal reviews (Kine Weekly, 15 June 1961; Daily Cinema, 21 June 1961), as well as Anglo�s original publicity releases, reveal nothing to suggest that this film had a Wallace connection/origin. Neither TV Archive nor I include it in the Merton EW series.

The Malpas Mystery (1960), listed by TV Archive in its list of IA films, was a Merton Park Studios-Langton production, according to the reviews in Monthly Film Bulletin [UK] (February 1961) and Variety (21 May 1969 for the US release). Kine Weekly (15 December 1960), however, confirms that it was indeed produced by Wintle & Parkyn at Beaconsfield Studios. It is, nevertheless, an EW entry.

Urge to Kill (1960) is included as an early Merton film by TV Archive, but, it seems, it was not produced as a part of their Edgar Wallace or Scotland Yard series, and I have excluded it.

There are seven other films cited by TV Archive which are all Merton productions (1963-1965) but, to all appearances, these are not related to any of their �series,’ including Scotland Yard and Scales of Justice.

Thus of the 47 films in the Classic TV Archive count, I add one (Malpas) and delete eight others. This takes the “Edgar Wallace” count to the 40 titles I have listed above.

Incidentally, Game for Three Losers (1965) — part of the TV Archive “seven” — was based on a novel by Edgar Lustgarten (screenplay by Roger Marshall; directed by Gerry O’Hara), but does not appear to be part of the Scales of Justice or any other series.

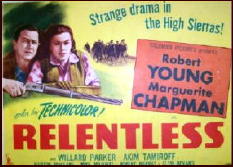

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.