Search Results for 'mysteries'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 11 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

EDWARD D. HOCH – Nothing Is Impossible: Further Problems of Dr. Sam Hawthorne. Crippen & Landru, 2014. Introduction by Janet Hutchings. Collection: 15 stories from EQMM.

For Edward D. Hoch (1930-2008), mysteries were primarily about plot, with characterization necessarily taking second place. The knottiest kind of mystery plot has always been the “locked room” or “impossible crime” story, which of necessity calls for more than the usual amount of cerebration on the parts of both the writer and the reader, who is expected to participate in the “game” of “howdunnit” set up by the author.

During his career, Hoch outdid even the grand master of the locked room mystery, John Dickson Carr, in the number and variety of his plots, churning out these brainbusters on a production line basis.

Hoch had several series characters threading their way through his nearly one thousand short stories, among them Ben Snow, Simon Ark, Rand, Captain Leopold, Nick Velvet, and Dr. Sam Hawthorne. It was in the stories of that last worthy, a New England general practitioner, according to Janet Hutchings (Hoch’s editor at Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, EQMM) in her introduction, that “one finds some of the best Hoch plots, perhaps because he liked to save the most difficult kind of puzzle, that of the locked room, for his country doctor.”

Hutchings contrasts Dr. Sam with one of Agatha Christie’s series characters:

“… unlike Miss Marple [of St. Mary Mead], Dr. Sam Hawthorne is not primarily an observer of his town [Northmont] — he’s an active participant in all that goes on…

“As a young single doctor, Dr. Sam is involved in all kinds of relationships — personal, professional, and civic — with characters who turn out to be suspects, victims, and witnesses. He has a stake in what happens that goes beyond achieving justice, and his supporting characters become more important, as the series progresses, than they ever could be were his primary role that of observer.”

Thus Hoch was able “to create a milieu that readers could look forward to returning to again and again.” His entire series of Dr. Sam stories would begin in 1922 (the Roaring Twenties), pass through the Depression Thirties, and end (due to his death) in 1944 (the War Years), with the ones in this collection covering the period from early 1932 to late 1936.

If you like impossible crime stories that are puzzling without being disappointing in their solutions then Edward D. Hoch’s Dr. Sam Hawthorne stories are a good place to go. Unless you’ve collected just about every issue of EQMM since 1974, however, it’s unlikely you’ll have the complete series, which is why you’d do well to get this book — and the two previous Dr. Sam collections issued by Douglas Greene’s fine publishing house, Crippen & Landru.

— NOTE: A slightly different version of this article appeared on The American Culture website.

Tue 10 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

LOUIS BAYARD – The Black Tower. William Morrow, hardcover, August 2008. Harper Perennial, paperback, 2009.

“We never solve a damn thing really. We just make more questions.â€

Eugene Francois Vidocq remains one of the most illusive and fascinating men in history. Convict, thief, fence, police spy, master of disguise, founder of the Surete, the first modern detective force, bestselling author, the first private detective, forensic pioneer in ballistics, fingerprints, and footprints, a man who escaped from every major penal institution in France, and the model for such literary giants as Poe’s Dupin, Balzac’s Vautrin, both Hugo’s Jean Valjean and Javert, and in spirit Sherlock Holmes.

He was gargantuan in size, appetites, genius, and ego. But he has always remained elusive in fiction, a figure so outlandish that the truth about him is too fictional to be believed or conveyed without testing the readers willing suspension of disbelief.

In Douglas Sirk’s film A Scandal in Paris with George Sanders as Vidocq they had to tone down the man’s character considerably, because no audience would have believed the truth.

In The Black Tower Louis Bayard has corrected that problem, giving us not only Vidocq in his full glory, but a mystery worthy of him, the hunt for the true fate of the dauphin, the heir to the throne of France — Louis Charles, Louis the Seventeenth, the child of Louis Sixteenth and Marie Antoinette — the lost king.

It’s a mystery that has resonated since the early half of the 19th Century. What happened to the ailing child imprisoned in the infamous black tower apart from his family, and doomed to die by the fanaticism of the French Revolution, the Jacobins, and the Terror? Other novels have dealt with it (Dennis Wheatley’s Roger Brook novel The Man Who Would Be King) and much non-fiction as well, but the questions are unanswered and likely remain so.

That hasn’t stopped Louis Bayard (Mister Timothy, The Pale Blue Eye) from weaving a magical literary thriller out of a spider silk of questions, legend, rumor, history, and Vidocq himself, one of the most fascinating men of his age. In addition to its other qualities it is also one other thing, a damn good detective story, featuring the world’s first detective.

It is 1818 and France, still reeling from the Revolution, Napoleon, and Waterloo, is in the midst of the Restoration of the throne upon which sits a new king. In the Paris of this turbulent time is one Hector Carpentier, a medical student languishing in his mother’s home, and about to find himself drawn into one of the great unsolved mysteries of all time.

It all begins when Vidocq, in disguise, shows up on Hector’s doorstep with a question, who was Monsieur Leblanc (surely a nod to the creator of Arsene Lupin, another Vidocq figure), the man murdered on the way to Hector’s home. Hector has no idea, nor any suspicion that he is being drawn into conspiracy from the past and the present that is as deadly now as it was then.

… if I had to write up my life I don’t think I could start with all the usual genuflections … No, I’d have to start with Vidocq. And maybe end with him, too.

Though the mystery is compelling, the characters lively, and the setting superbly drawn everything in the book falls beneath Vidocq, a figure whose shadow at times seems to dominate all of France. Bayard’s portrait of him is one of the books great pleasures, his vivid descriptions of the man’s moods and styles forms a fascinating and vivid portrait of one of those historical figures who would have to have been invented if he didn’t really exist.

The mystery grows deeper: there is the Duchesse d’Anguoleme, the dauphin’s sister, who survived the Terror but feels guilt about abandoning the young Louis and her mother; the Baroness de Preval, widow of the Austrian ambassador who begins the hunt for the dauphin and who has secrets of her own, the new king of France who is willing to kill to keep his throne; Charles Rapskeller, a young man who may well be Louis; Herbaux the assassin; and three men, one of them Hector’s father, who took pity on a sick child held in a block tower and now from the grave may restore the rightful king of France.

There seems a new twist or mystery at every turn. Hector and Vidocq play each other each for their own goals while establishing a deep friendship, as secrets are revealed that turn the very tide of history, for no one is more anxious to find the true dauphin than his mother … Marie Antionette.

There is no shortage of mystery, action, escape, suspense, heart, or fascination in the novels rapid paced but carefully drawn plot, and Bayard’s prose and turns of phrase are a delight to read:

Square and proud and blunt, built on geographical lines.

***

And here his fingers form a bud round his mouth and the name flowers forth, like a shower of pollen.

“Vidocq.â€

***

“If you have another lost king to peddle, Madame, you’ll have to knock on someone else’s door.â€

“I’m peddling nothing,†she answers, the first touch of frost crisping her voice. “It was Leblanc who believed, not I. And if he was wrong,” she says, rising and fronting him, “May I ask why he is dead?â€

She waits, with great courtesy, for his answer. Then tilting her head in deference, she asks: “Surely, there would be no need to kill a man who was laboring under a delusion.â€

It is a delightful book, a truly great read in the tradition of Zafon, Perez Reverte, Eco, Matthew Pearl, and yes, though there is no locked room or miracle crime, John Dickson Carr. It is simply a superb old-fashioned book book, a page turning, mind and heart engaging, first class read, and at its center, one of the most fascinating mysteries of all time, not what happened to the dauphin; but Eugene Francois Vidocq himself.

Tue 13 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

C. S. HARRIS – What Remains of Heaven. New American Library, hardcover, November 2009; trade paperback, August 2010. Signet-Obsidian, paperback, August 2011.

If all you know of Regency England are rakes and ladies, duels and male vanity, Jane Austin and Georgette Heyer, then you may be surprised by this fairly dark mystery by C. S. Harris, a historian with an eye for the telling detail. There are no faughs or deuced clevers and no Scarlet Pimperneling, and our handsome hero is balanced by the attractive but annoyingly independent Miss Hero Jarvis who has a taste for women’s sufferance a good eighty years too early for Regency society. She isn’t the fainting type, and he’s a Regency rake with an annoying conscience.

A former soldier, Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount of Devlin (a viscount is a cousin of royalty) was introduced along with Hero in What Angels Fear and this is their fifth outing. Here the controversial reformer the Bishop of London is found in a crypt murdered by the body of an unknown victim of of a murder decades earlier.

St. Cyr is in no hurry to take up a case — his last one estranged him from his father for a year, and they are only now mending fences — but his aunt, the Duchess of Clairborne, shows up at his Brooks Street rooms with the Archbishop of Canterbury in tow wanting him to investigate, as his aunt snidely informs him: “Because your good at it, of course.â€

So St. Cyr is stuck joining forces with Bow Street magistrate Sir Henry Lovejoy in digging around the crypts looking for clues while Paul Gibson, ex-army doctor with a surgery in Tower Street, examines the body since “nobody knows more about dead bodies …â€

Meanwhile St. Cyr’s father the Fifth Earl of Hendon, current Chancellor of the Exchequer, has been approached by the Regent to form a government, which will throw him again into conflict with a powerful enemy the king’s physically and politically powerful cousin Charles, Lord Jarvis.

And all St. Cyr has to work with is Tom, his thirteen year old sharp faced protege and aide, and of course Hero, the daughter of Lord Jarvis and the Prince Regent’s greatest enemy. And just to complicate things, Hero is pregnant with St. Cyr’s child and heir.

The stage set St. Cyr sets about some creditable detective work in a Sherlockian vein — St. Cyr, we are told, is tall, lean, and possessed of “feral yellow eyes†— as a not so simple murder winds back thirty years earlier to the days of Sir Francis Dashwood and the infamous Hellfire Club as well as to the government in contemporary Whitehall.

Action, atmosphere, politics, genuine detective work, a historically accurate and beautifully drawn portrait of a fascinating era, smart likeable heroes, dangerous conspiratorial villains, and a desperate murderer driven by fear. What more could you ask for?

Noble families, including St. Cyr’s own, prove to have desperate secrets to keep, the government may not want certain things brought to light, there is a ruthless killer on the loose, the romantic subplot spins out of control, and St. Cyr proves to be a likeable if reluctant and somewhat roguish swashbuckling sleuth perhaps just a little over-matched by Hero Jarvis, who is not looking to trade a father for a husband even if she is with child.

Will Thomas, author of the Barker and Llewelyn novels, called Harris last a “ripping read,†and if you know his work he is no shirker at ripping reads himself. This has a little bit of everything, and I am certainly going to look into the other books in the series.

Harris also writes contemporary thrillers as C.S. Graham, and I’ll be looking for those as well. While her plot and style are not Carrian and she eschews miracle problems, at her best the atmosphere, historical accuracy, mysteryfying, and well drawn characters true to their time — all remind me of John Dickson Carr’s better historical mysteries, no small praise from me.

The highest recommendation I can personally give a book is ‘Damn good read.†What Remains of Heaven is a damn good read.

The Sebastian St. Cyr series —

1. What Angels Fear (2005)

2. When Gods Die (2006)

3. Why Mermaids Sing (2007)

4. Where Serpents Sleep (2008)

5. What Remains of Heaven (2009)

6. Where Shadows Dance (2011)

7. When Maidens Mourn (2012)

8. What Darkness Brings (2013)

9. Why Kings Confess (2014)

Fri 2 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

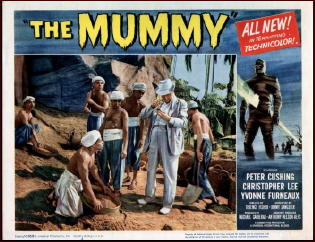

THE MUMMY. Hammer Films, UK, 1959. Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Yvonne Furneaux, Eddie Byrne, Felix Aylmer, Michael Ripper. Screenplay: Jimmy Sangster. Director: Terence Fisher.

Over the past fifteen years or so, film and television writers have embraced both fanged vampires and, to a lesser extent, furry werewolves. With the exception of The Mummy (1999) and the franchise it launched, mummies, those aristocrats ensconced in linen and raised from the dead, have not played prominent roles as villains. This is unfortunate.

Not only are mummy tales, when critically unwrapped and analyzed, as terrifying as vampire yarns. They also provide a fascinating insight into how Anglo-American filmmakers have understood their particular era’s relationship to the ancient Egyptian past. From Napoleon Bonaparte’s first campaign in Egypt (1798) and British Museum’s Rosetta Stone exhibit (1802-present) to the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb (1922), the mysteries of long-vanished Egyptian civilizations have piqued the curiosity of western observers.

Mummy films are the cinematic representations of this strange, enduring fascination. The two best-known mummy films are undoubtedly Universal’s The Mummy (1932) starring Boris Karloff and the aforementioned 1999 quasi-remake starring Brendan Fraser and Rachel Weisz.

But there’s also a 1959 mummy film that deserves ample consideration. The Mummy, starring Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and Yvonne Furneaux, is perhaps the least known of the three films of the same name. To varying degrees, the plot is borrowed from three previous, even lesser known, mummy movies, The Mummy’s Hand (1940), The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), and The Mummy’s Ghost (1944). Directed by Terence Fisher, The Mummy (1959) is a Technicolor Hammer Production with great horror film acting, lavish and colorful settings, and an excellent, memorable score composed by Franz Reizenstein.

The film begins with an archaeological dig in Egypt. It’s 1895 and three members of the same family discover the tomb of Princess Ananka, the high priestess of the ancient Egyptian deity, Karnak. Because John Banning (Peter Cushing) is injured and somewhat immobile, the English archeologist’s father, Stephen Banning (portrayed by Felix Aylmer), is tasked, along with his uncle Joseph Whemple (Raymond Huntley), with entering the tomb.

Along comes Mehemet Bay in a red fez (portrayed by the Cypriot character actor George Pastell). He warns the two men against disturbing the dead, lest they unleash a curse against desecrators. As you might imagine, the enterprising Englishmen don’t heed the warnings of this excitable foreign fellow.

Skip to three years later. It’s 1898 and Stephen Banning is back in England. Sadly, the poor chap’s gone completely mad. His son, the scholarly John Banning, is now ambulatory and living with his wife (Yvonne Furneaux). Life is apparently pretty good for the younger Banning, who appears to be living a plush life on an English country estate.

But good things never seem to last for those who disobey warnings not to disturb the dead. We know that there’s trouble ahead when Mehemet Bay arrives in England on a quest to avenge the opening of Princess Annaka’s tomb. After Stephen Banning is found dead in his room (murdered by the mummy Kharis), a police inspector by the name of Mulrooney begins to investigate the mysterious goings on.

Through extensive flashback scenes narrated by Peter Banning (Cushing in a quite memorable voice-over role within the film), we learn that Kharis (Lee) was the high priest of Karnak. Centuries ago, Egyptian authorities mummified Kharis and buried him alive as punishment for his attempt to bring Princess Annaka (also portrayed by Yvonne Furneaux), whom he loved, back from the dead.

The second half of the film revolves around Mehemet Bay’s attempt to utilize Kharis to kill the other two Bannings before heading back to his native Egypt. There’s a notable scene in which Peter Banning and Mehemet Bay tensely discuss the ethics of archeology, perhaps a subtext about London’s historical meddling in Egyptian affairs.

If the plot sounds somewhat convoluted, you’ll have to trust me both when I say that it’s really not and, even if it were, it really wouldn’t matter all that much. In many ways, plot isn’t what makes this version of The Mummy a classic horror film worth watching at least once.

It’s the filmmakers’ skillful use of color and lighting, particularly when combined with Reizenstein’s score, which transforms a film with an otherwise standard mummy-seeks-revenge plot into a captivating cinematic experience. Although the Egyptian scenes are clearly sets and not filmed on location, there’s something about them that makes them incredibly vivid.

One final note: while watching The Mummy on DVD, I kept thinking how much I’d like to see the film in a dark movie theater, particularly one with a great sound system. Who knows? Maybe some day, I shall.

Wed 23 Apr 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

J. J. CONNINGTON – Death at Swaythling Court. Little Brown, US, hardcover, 1926. First published in the UK by Ernest Benn, hardcover, 1926. Penguin, UK, paperback in jacket, 1938.

In the usually quiet village of Femhurst Parva, one Hubbard, butterfly collector and blackmailer, has, according to a coroner’s jury, committed suicide.

Outside the jury his death creates many questions. Who stabbed him after he poisoned himself, if he did indeed poison himself? Who used a candle and for what in a well-lighted room? Who stole a butterfly?

There are too many clues, all of which seem to point in different directions. And don’t forget the local inventor’s Death Ray, the village legend of the “Green Devil,” who apparently is keeping up with the times by using the telephone, and the Invisible Man.

This is a splendid example of the English-village novel. The characterization doesn’t go deep, particularly with Colonel Sanderstead, who investigates, but then he isn’t deep. The fair play promised by the author is here, and I’ll brag and say I got about two-thirds of it right. Fine stuff from the Golden Age.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Editorial Note: On the occasion of three of J. J. Connington’s mysteries having recently been reprinted by Coachwhip Publications, Curt Evans wrote a long article about the author and the three books and posted it on his blog. Check it out here.

Wed 12 Feb 2014

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

#17. OLD CALAMITY, by Joseph Fulling Fishman.

Joseph Fulling Fishman created the prison series (ran 1928-1939) for Detective Fiction Weekly about the jailer Old Calamity, making use of his knowledge of crime and prisons. In fact, Fishman wrote more nonfiction articles on these subjects from 1925-1942 for Detective Fiction Weekly than stories in the fiction series.

He also wrote articles for other magazines such as Reader’s Digest and The Saturday Evening Post, and books about crime and prisons. Fishman was a 1931 choice for a Guggenheim Fellowship. He was awarded a grant for being chosen. According to Wikipedia, the Fellowships “have been awarded annually since 1925 by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those ‘who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the arts.’ â€

The name Old Calamity is what the three thousand inmates of the state prison at Cosmopolis call him. The guards and other personnel call him Ole Dep Fletch out of his hearing. His real name is Deputy Warden Fletcher, and even though there is a warden who is a political appointee, Fletcher is really the one running the prison.

The wardens of the prison were all political appointees, but Fletcher was a professional jailer. The wardens were appointed by the state governor, but the governor on one occasion said: “You know, Fletcher. You’re really the one I should appoint warden, but of course there’s politics . . .†(Old Calamity’s Stick-up)

“Thirty years of combating the plots and counterplots and the intrigues and chicanery of thousands of inmates of every degree of criminality and cunning and viciousness . . . had sharpened the perceptions of the Deputy Warden.†(Old Calamity Starts a Fight)

This long experience gave Old Calamity an advantage when dealing with the many problems that he came across in his job. He knew just about every trick the convicts tried, and how to deal with them. He enjoys his work, and at one point turns down a job offer from a rich businessman with the comment “I’m afraid not, thank you,†Old Calamity replied. “I’m doing the kind of work I like and that’s worth more than money.†(Old Calamity Sniffs a Clue)

He usually went to work in the prison at seven in the morning, and had a regular routine except when emergencies or problems interrupted. His usual morning routine was “supervising the count, reading his mail, making assignments of new prisoners, and so on, . . .†(By a Nose)

He doesn’t let the routine of everyday work get himself in a rut where he overlooks things; he notices the smallest detail of what may turn out to be very important to him and the prison. Probably why he has lasted so long in his job.

The stories are basically all about Old Calamity, with very few appearances by a regular cast of characters. One regular is Croaker Engle, the “brusque old prison doctor.†His appearances in the stories are usually very short. Before him, a Doctor Cosgrove made a single appearance in the story “Fine Feathers.â€

The prison warden is mentioned in the stories, but plays very little part in the stories. An exception to this are the stories “Old Calamity Starts a Fight,†and “Between the Lines,†where part of the story takes place around the warden. The warden of the prison is replaced at one point in the series. The warden and Old Calamity both have homes right next to the prison grounds.

The stories usually involve murder in the prison by inmates murdering other inmates, for various motives. Prison breaks and conspiracies aimed at escaping prison are also elements in the stories. Fletcher has to break up the escapes, which sometimes are very cleverly planned.

In the story “Old Calamity Scores Twice,†he not only has to foil a planned escape, but solve a clever locked cell murder made to look like suicide. In “Between the Lines,†he literally has to read between the lines of a prisoner’s book reading material to discover a plot to escape using explosives.

The earliest story in the series, “By a Nose,†involves uncovering a murder by bomb and finding the culprit. His investigations of various kinds involve him acting more as a detail-oriented detective than as a deputy warden.

Another concern of prison authorities is the use of illegal drugs by the inmates. The story “Fine Feathers†relates the attempt of Old Calamity to stop the flow of drugs into the prison, and in a later story, “Old Calamity Starts a Fight,†the problem of drug usage is also the main theme. This is certainly based on situations in real prisons at the time. Morphine is the drug mentioned in these stories.

“Fine Feathers†relates some of the problems that drug usage by inmates causes – aggressiveness and fighting by prisoners, and other irrational behavior. One prisoner high on drugs even set his cell on fire.

One story showed Old Calamity on vacation, enjoying relaxing fishing. However, the local law enforcement find out he is there and enlist his aid in solving a series of inexplicable burglaries. (Old Calamity Sniffs a Clue)

This use of Old Calamity’s talents outside his own prison was not the only time this occurred. It appears that he was available for aid at other prisons having problems. In the story “The Suicides in Cell 32,†he travels to Milford State Prison to help investigate a series of murders made to look like suicides.

Warden Olmstead of the prison knew of his reputation and had requested his help. In less than twelve hours Old Calamity has solved the mystery and was on his way back to his own prison. He noted: “I guess that some of the birds up at my place will be sorry it didn’t take me several weeks. I’m afraid they won’t be any too glad to see me back in the morning.â€

In “Old Calamity Lays the Ghost,†he travels to another prison in Springdale in response to another request for help. Warden Armitage of the prison has a mystery for him to solve: twice men in their cells have been stabbed and nearly killed. In both instances knives were found in the cells, but no evidence was found as to how the men could have been stabbed inside of locked cells.

Old Calamity finds an ingenious method has been employed in the stabbings. It took him a few days to resolve this one, but he had developed the patience to wait for the right time. “He had often waited weeks and sometimes months for the development of a prison plot. He knew it was something that could not be hurried, . . .â€

The series is very good in its story telling and relation of the various mysteries Old Calamity is involved in. Altogether, Fishman’s descriptions of prison life and the psychological aspects of the stories seem to be very convincing, and made the stories more than mere sensationalistic prison stories such as other pulp writers wrote.

The “Old Calamity” series by Joseph Fulling Fishman:

By a Nose October 27, 1928

Fine Feathers February 2, 1929

The Yawn March 2, 1929

Old Calamity Stages an Act April 6, 1929

Old Calamity Lays the Ghost April 9, 1932

Old Calamity Holds the Wire July 23, 1932

Old Calamity Starts a Fight September 17, 1932

Old Calamity Scores Twice February 11, 1933

The Suicides in Cell Thirty-Two June 17, 1933

Between the Lines September 9, 1933

Old Calamity Sniffs a Clue April 7, 1934

Old Calamity Cleans Up May 19, 1934

Old Calamity’s Stick-up June 23, 1934

Old Calamity Stops a Leak June 5, 1937

Honor of Thieves March 18, 1939

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by Harold de Polo.

12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.

13. HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE, by J. Lane Linklater.

14. HANIGAN & IRVING, by Roger Torrey.

15. SENOR ARNAZ DE LOBO, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

16. DETECTIVE X. CROOK, by J. Jefferson Farjeon.

Sat 11 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

VERNON HINKLE – Music to Murder By. Belmont Tower, paperback original, 1978. Leisure, paperback, later printing.

A good friend sent me this mouldering paperback mystery, knowing of my fondness for mysteries with a classical music connection. And it begins with a discussion between two old friends of the performance of Ravel’s “Bolero” at a Boston Symphony concert they have just attended.

I won’t pretend that this is a work for the ages, and the style is, at times, leaden, but the plot is neatly developed, concluding with a classical gathering together of all the suspects by the amateur detective who proceeds to pull the numerous threads together and reveal the murderer’s identity.

The protagonist is a music librarian, a rather fussy bachelor who has a gift for puzzle solving and quickly succeeds in persuading the homicide detectives that he will be able to solve their case for them. This takes something of a stretch of the imagination, since it involves detective squads in both Boston and New York, and the librarian, one Martin Webb, conveniently is the first to arrive at both murder scenes, creating some question about his own involvement in the crimes.

The characters include a somewhat comical Boston patrolman, a would-be novelist and his ex-wife and current girl friend, a YMCA desk clerk, and a gaggle of porn movie performers.

Hinkle also published Murder After a Fashion (Leisure, 1986) and, writing as H. V. Elkin, a Western series. In an interview recorded in Contemporary Authors, Hinkle comments he regards “most fiction as mystery … in the sense that each piece … is a puzzle or a quest for unknown answers.”

And that’s my Visit to the Dusty Archives for this session.

Tue 7 Jan 2014

SHANNON OCORK – End of the Line. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1981. No paperback edition.

This reads very much as it’s supposed to, which is to say like a story told by a liberated young lady working with some caution and care in a world dominated by men. T.T. (Teresa Tracy) Baldwin is an aspiring sports photographer for the New York Graphic. She also solves mysteries.

A murder occurs at a shark-hunting tournament, and it goes without saying that [from an author’s point of view] the lesson learned from the popularity of Jaws is not lost on Shannon OCork before the case is closed. There are also some missing diamonds and an antagonistic small-town cop who is solidly in a rich man’s pocket.

As a mystery, the story is sometimes a puzzler in more ways than one. Obvious questions (to the reader, at least) arc never asked, apparently never even thought of, until at length T.T. reveals she already knew the answers, far earlier than she ever let on.

From another point of view, the broken style T.T. persists in using in telling her own story adds immediacy to the first part of the narrative, and a considerable amount of fast, page-turning excitement to the finale. In between, it simply becomes hard to read.

Other than T.T., who is bright, smart-alecky, and certain to get ahead, most of the remaining characters are straight from summer stock. The ending is worth waiting for, however.

Rating: B minus

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 6, No. 3, May-June 1982 (slightly revised).

Bibliographic Notes: T.T.Baldwin had a three book career. End of the Line was preceded by Sports Freak (St. Martin’s, 1980) and followed by Hell Bent for Heaven (St. Martin’s, 1983), neither of which do I remember ever seeing. As for the author herself, she was married for twelve years to mystery writer Hillary Waugh and in 1989 wrote a book for would-be mystery writers, appropriately titled How to Write Mysteries.

Thu 2 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

MILES BURTON (Charles John Cecil Street, MC, OBE, 1884-1965) — The Secret of High Eldersham. Mystery League, US, hardcover, 1931. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1930.

I can testify that the portrayal of East Anglia in this novel is fairly accurate, at least it still was in the 1970’s. It’s a somewhat insular part of England, friendly enough on the outside, but slow to accept strangers, and like many small communities prone to suspicion of anyone and anything new. You can spend thirty years of your life their and still be a foreigner, even if they like you. Simply living there does not make you one of them.

There are certainly towns like that here as well, but it is pronounced in East Anglia — and in High Eldersham, a village of some three hundred people the insularity is particularly pronounced. A few families have intermarried until everyone is related to everyone else, and there is nothing but distrust for strangers. In High Eldersham newcomers tend to have ill fortune, they seldom stay long.

But Mr. Thorold had a long experience of strangers as tenants in East Anglia. However hardworking and conscientious they might be, however keen to promote trade, the receipts of their houses had a way of falling off until they were perforce compelled to relinquish their tenancy. And this curious distrust of strangers, common throughout East Anglia, was particularly active in remote villages like High Eldersham. Yet Dunsford had said that no local man would take the Rose and Crown, and he knew every soul in the village and for miles around.

Burton is good here showing the impact of the First World War on small English villages, both socially and economically. Still, murder is carrying it a bit far so far as local Constable Viney is concerned when he finds the publican of the Rose and Crown, Edward Whitehead, Mr. Thorold’s chosen outsider tenant, a retired sergeant of the Metropolitan Police force, stabbed to death in his chair.

The Chief Constable is by no means sure of local Superintendent Bateman’s ability to handle a murder of this sort, so against the other man’s wishes he asks for help from New Scotland Yard (the detective branch of the London Metropolitan Police, not a national police as sometimes implied in detective stories — still well through the sixties small police forces did sometimes call on the Yard for help — as is done here, and Yard investigations may lead almost anywhere in England, or the world).

Help arrives in the person of Inspector Young (whether as Burton, Waye or Rhode, his policemen tend to be efficient and capable), who enlists Constable Viney as a local expert, and handles himself quite well, but as his first few leads fail to pan out Young decides to call on a wartime friend for help.

During the war (WWI) Young frequently had dealings with the Naval Intelligence branch of the Admiralty, and in the person of a bright fellow he quite admires, Desmond Merrion (Merrion usually works with the competent Inspector Arnold, who debuts in a later adventure).

Merrion is strictly an amateur, not even classifying himself as a detective, but he’s an attractive sleuth along with his man, the capable Newbolt, and I always found him easier to take than the more stately Priestly (not to say anything against the best Priestly’s — I particularly enjoyed The Murders in Praed Street and The House on Tollard Ridge). This was the first outing for Merrion, and the best.

Charles John Cecil Street was Miles Burton, Cecil Waye (author of husband and wife private investigators Christopher and Vivienne Perin in four titles between 1931 and 1933), and John Rhode, one of the staples of the Detection Club, and creator of another great detective, the scientific sleuth Dr. Priestly.

Street was a proponent of the fair play mystery, and a spinner of solid puzzles that on occasion even developed a bit of suspense and action. Julian Symons qualifies him as being of the humdrum school. [FOOTNOTE] (Barzun and Taylor disagree in A Catalogue of Crime and review several books enthusiastically, including this one — I tend to lean toward their view), there is nothing humdrum about The Secret of High Eldersham, however.

In later years (he was still penning Priestly and Merrion novels into the early 1960‘s) Street could be frightfully humdrum to the point of boredom, and unlike Marsh, Christie, Carr, Innes, or Allingham, who all lived and kept writing longer than him, he didn’t manage to modernize much past WWII or hold on to more than a few diehard fans. He is likely best known today for his collaboration with John Dickson Carr (writing as Carter Dickson) Fatal Descent (1939 UK title Drop to His Death), written as Rhode.

Humdrum or not Street was never a bad writer, and some of the early books are highly collectable, but as I said the later books don’t offer much, and frankly for me, they read as if he was just churning it out without the inspiration or the enjoyment of his earlier work. Failing health may also have contributed to the decline. The kindest word I can think of for them is tired, but then having been prolific since the twenties (I count seventy-one Priestly novels and sixty-three Burtons between 1925 and 1961), he was entitled to tired at that point.

In addition to his prolific mystery fiction he wrote non-fiction, often dealing with international politics, and short stories, theater (unproduced), and radio plays (featuring Priestly and Inspector Jimmy Waghorn from the Priestly series). He wrote at least one memoir of his service as a gunnery officer in the First War, and one of his service in Ireland as an Intelligence officer.

That doesn’t matter here, because The Secret of High Eldersham is one of the highlights of his long career, and for my money the best of the Merrion novels. This one has a bit of everything all perfectly balanced between detection, action, and deeper mysteries than mere murder. Something old and evil is brewing in High Eldersham, and anyone who stands against it meets a terrible fate.

When Constable Viney is struck down by a mysterious illness Merrion begins to suspect a broad conspiracy at work (many of Burton’s books feature large criminal enterprises — something a bit different than the more personal murders of many of his contemporaries — not to suggest the others didn’t deal with their fair share of criminal conspiracy and even international intrigue).

It looks to me as though the High Eldersham people suspected, if they don’t actually know, that somebody about the place murdered Whitehead. If they thought it was a stranger, they’d be only too ready with information. As it is, they are convinced that the man met his death in consequence of the spell cast upon him, and the example of his fate is quite enough to induce them to hold their tongues.

There is even an unobtrusive romance for Merrion that figures neatly into the plot causing him some real consternation and anxiety and introducing Merrion to his wife to be, Mavis Owerton, daughter of local landowner Sir William, one of the suspects to Merrion’s chagrin. Burton handles the romance quite well.

Side by side they walked down through the park. The fog had descended thicker than ever, and without Mavis’s guidance Merrion would inevitably have taken the wrong path. She led him to where the dinghy was tied up, then suddenly, as he was about to step into it, she laid a hand upon his arm. “You’re not going to do anything dangerous are you?†she asked softly.

He swung round and faced her. There was a note of solicitude in her voice which made the blood run madly through his veins. Obeying a sudden impulse he caught her in his arms. She lay there for an instant, then gently disengaged herself.

Breathing one last word, “Mavis!†he stepped into the dinghy and picked up the oars. The girl’s figure faded from his eyes into the surrounding mist.

It’s a grown up romance, and doesn’t get in the way for once. Merrion’s concerns for Mavis are genuine and justified, but never descend to the silly ass behavior of some other classic sleuths in love. The Detection Club rules frowned on romance, but just about all the original members broke the rule in one book or the other. It’s Burton’s turn here.

In his early days as Rhode he was prone to the popular theme of the twenties, drug smuggling, especially cocaine. As Rhode, he even wrote a non series book more or less on thriller lines, The A.S.F. The Story of a Great Conspiracy (1924, US title The White Menace).

The drug theme raised its head in his work once in a while after that as it does here, and a nastier lot of smugglers, secretive islanders, villains, devil worshipers, and at least one murderer more sinister than East Anglia ever saw, have seldom inhabited the pages of a mystery. Deviltry is the least of it, in a very real sense, and quietly evoked by Burton, a community’s soul is at risk.

The stone was undoubtedly the altar behind which officiated the devil, the mysterious president of the coven. A glance at the sides of the stone confirmed this. It was carved with strange figures, the obscure symbols of an almost forgotten rite. A sudden horror seized him, the malign influence of this ill-omened grove.

Action, atmosphere and suspense aren’t usually the virtues you tend to associate with Burton or Rhode, but in the early Priestly novels he managed some well staged suspenseful scenes revealing the murderer, and here, taking advantage of East Anglia’s remote dramatic countryside, and his well drawn portrait of High Eldersham and its environs, he provides atmosphere, action, a chase, even a coven, a close encounter with death for Merrion and his girl, a damn good piece of mystery and detection,and there is also some well done business handling small boats. It’s a very physical as well as intellectual and disturbing investigation for Merrion.

The psychology of the thing seems fairly simple to me. The members of the coven derived a definite advantage from the ceremonies. Any one against whom they had a grudge suffered accordingly. But things were a good deal deeper than that. The real attraction was the drugs mixed in the bowl which was handed round, and the sensations they produced. It’s all pretty horrible, but there isn’t the slightest doubt that the meetings ended in an orgy of promiscuous lust, no doubt excited by some form of aphrodisiac. If you study some of the old records, you’ll find these things described in detail. H——–‘s (my annotation to save a spoiler alert) whole idea, of course, was to turn the village into a more or less criminal society …

Granted that sounds more like Dennis Wheatley than Burton or Rhode, and violates all the Detection Club rules save for Chinese chicanery (frankly that drug he describes pretty much is a ‘drug unknown to science’), but you’d have to be a pretty narrow stickler or curmudgeon to care.

This is not a tour de force, but it is perhaps the best book by one of the early masters of the form, highly entertaining, and certainly not the least dull. It is easily the fastest read by Burton or Street I know of.

But Merrion acquired property in High Eldersham, even before he was married. He bought the island which had been the scene of so many strange ceremonies, and, on the night after the purchase was completed, he and Newport went there, armed with sledge hammers, and broke the altar into little pieces, which they threw into the river.

“Reminds me of that chap in the Old Testament, sir,†remarked Newport, as he mopped his brow after his labours. “What was his name, sir?â€

“Gideon. ‘Throw down the altar of Baal that thy father hath, and cut down the grove that is by it.’ Yes, I think we’ll make a job of it, and have these trees down too. Things haven’t changed much since those days, have they?â€

The perfect end to what I consider an almost perfect book of its kind and a satisfying read both for the detective story lover and those that want a bit more accompanying it. If you read only one book by Burton or Rhode, this is the one I would suggest. I consider it one of the true highlights of the Golden Age, a masterpiece of its kind, by an old master.

[FOOTNOTE] Symons defines the Humdrum School thusly for those of you unfamiliar with the term: “Most of them (the Humdrums) came late to writing fiction, and few had much talent for it. They had some skill in constructing puzzles, nothing more, and ironically they fulfilled much better than S. S. Van Dine his dictum that the detective story properly belonged in the category of riddles or crossword puzzles. Most of the Humdrums were British, and among the best known of them were Major John Street …”. — Julian Symons, Bloody Murder.

Sun 15 Dec 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

ROBERT GALBRAITH (J. K. ROWLING) – The Cuckoo’s Calling. Mulholland Books, US, hardcover, 2013. First published in the UK by Sphere Books, 2013.

It was no surprise that this critically acclaimed book went from near obscurity to bestseller status when it was revealed Robert Galbraith was none other than J.K. Rowling, the mega-selling author of the Harry Potter series. It was no real shock the book was well written. It may, however, come as a surprise to some readers who avoided the book that its virtues are its own and not second hand Pottery. The Cuckoo’s Calling is one of the better debut mysteries I’ve been lucky enough to read in recent years written by anyone under any name.

Cormoran Strike is a burly London-based private investigator who lost a leg in Afghanistan, and runs a one man operation. He’s more in the line of the Continental Op than Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade, and neither a mental or physical superman nor tarnished knight. If any kind of knight he’s the Green Knight whose wound never heals.

His artificial leg is a realistic problem, but never used as a gimmick. It’s something that happened to him and effects his life, but not melodrama. He’s not angry or bitter, but he isn’t happy about it either. It’s more often an obstacle and hindrance — or a source of unwanted vulnerability. For all his size, training, and toughness, vulnerable is a word you will associate with Strike.

We meet Strike as he’s about to hire a new temp from the Temporary Solution Agency. Her name is Robin Ellacott, an attractive twenty-five year old engaged to her boyfriend Matthew that same day. Robin is the closest the book gets to a character who might fit in the Harry Potter saga. She’s smart, she’s quick, and she is just a shade out of step with the world around her. She’s no Lucy Hamilton, Moneypenny, Della Street, or John J. Malone’s Maggie. She is more involved in the action and more important to it, something Strike didn’t know he needed, a crutch.

And she is thrilled when she finds out what Strike’s profession is; she’s dreamed about this since she was a child. An engagement and her fantasy job — what a great day.

She and Strike meet cute. He runs into her on the stairs and nearly sends her toppling. He’s gruff and just a bit wounded in a slightly romantic way and she is young and optimistic. He agrees to try her out, but only because he has a client coming. It won’t be for long, he can’t pay her what she should get anyway.

John Bristow is the client, and he thinks his half sister’s suicide was foul play. His sister was Lula Landry, the supermodel known as Cuckoo, and the reason for the haunted look in Cormoran Strike’s eyes. Lula wasn’t easy either: “… the lies she told were weaved into the fabric of her being, her life; so that to live with her was to become enmeshed by them, to wrestle her for the truth …”

She’s dead now and the fabric of lies has to be unraveled, even those he may have told himself to stay with her.

The case grows deeper, it becomes clear there was murder involved, and Strike finds himself relying more and more on the bright and empathic Robin. As the book progresses it is clear to us and to Strike that Robin is something he has needed for a long time, a connection with humanity.

Strike may not strike a Byronic figure at first glance, but the shadows haunting him are real and deep, the book is dark, but never gloomy, and Robin’s touch of optimism and a trace of whimsey keep Strike and the novel in balance. There is no Dis-Pollyanna voice here, no brutal violence in place of plot, no poor imitation of Spillane or Parker. This is a mature and exciting hard boiled mystery with what promises to be an important new protagonist.

This could easily have gone wrong in other hands, the Byronic wounded soldier either too much a romantic figure or too pitiable, but it is kept in perfect balance. You pull for Strike for the same reason Robin does, because he won’t give up, even when the darkness gathered in his soul tells him to. His one connection to Harry Potter may be that he is an orphan of sorts — especially from the army, as set apart by his artificial leg as Harry was by that scar on his forehead. The scars are visible reminders of the darkness that has touched them.

The pair find themselves plunged into the artificial world of multimillionaire models, designers, rock stars, drugs, champagne, and all that accompanies it until there is another murder, and Strike himself is in danger.

Long before this was revealed to be Rowling’s work it was getting critical praise if few sales (about 15 K in the UK — there was no American edition), many of them praising Galbraith for bringing the hard-boiled private genre back to life with an important new character in Cormoran Strike.

That may be the biggest shock here, it is a very good hard-boiled eye novel just realistic enough to feel real and just out of the ordinary enough to be fun. Strike may be the most promising and least derivative private eye since the boom of the eighties. I didn’t know what to expect when I gambled on this one, but I never expected how perfect the voice or how far from Harry Potter this is; only the literacy and insight are the same.

There is no question Rowling writes well. Even if you hate Harry Potter, the writing is very good. That’s true here. The style is nothing like Potter save being in the third person, but it is as perfect for this genre as it was for the juvenile fantasy.

A few examples:

His notebook lay open before him at a page full of truncated sentences and questions …

Even the pale pugnacious commuters squashed into the Tube carriage around her were gilded by by the radiance of the ring (Robin’s wedding ring) …

Instinct was clawing at him like an inopportune dog.

It stated to rain on on Wednesday. London weather; dank and gray, through which the old city presented a stolid front, pale faces under black umbrellas, the eternal smell of damp clothing, the steady pattering on Strike’s office window in the night.

He felt weary and sore, very conscious of the pain in his leg, of his unwashed body, of the greasy food lying heavily in his stomach.

We aren’t in Hogwarts anymore. Nor are we in the world of borrowed Chandler and Macdonald. She recognizes and plays with the genres familiar tropes, but she never relies on them for second hand atmosphere or shorthand in lieu of narrative.

I can’t oversell this. It’s that good, a well-written mystery, a well-observed novel, involving characters, a sense of threat and danger, heroes to cheer for, and believable bad guys to hiss. This is one of the most confident debuts I can remember in the hard boiled stakes. It isn’t perfect, few things are, but I’m concentrating on the good things because I know quite a few hard-boiled fans will likely be put off by the Harry Potter connection or even Rowling’s superstar status. She seems to have done something rare, step out of her comfort zone successfully and be accepted for it. Of course Harry Potter sales didn’t hurt, the Potter books had more than enough adult readers to propel this to the heights.

Rowling/Galbraith ends on a line of poetry appropriate to this book: I am become a name.

J. K. Rowling was already a name, but now so are Robert Galbraith and Cormoran Strike.