Search Results for 'Agatha Christie'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Thu 29 Jun 2017

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Dead Man’s Folly. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1956. Pocket, US, paperback; 1st printing, June 1961. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1956. Umpteen reprint editions exist, in both hardcover and soft. Made-for-TV movie: CBS, 8 January 1986 (with Peter Ustinov as Poirot, and Jean Stapleton as Mrs. Oliver). Also televised as an episode of Agatha Christie’s Poirot, ITV, UK, 30 October 2013 (Season 13, Episode 3), with David Suchet as Poirot and Zoë Wanamaker as Mrs, Oliver.

If you’ve never read this book, a folly is probably not what you think it is, not in the context of this particular story. Looking online, I found this definition, which is as good as any: “A costly ornamental building with no practical purpose, especially a tower or mock-Gothic ruin built in a large garden or park.”

I have a feeling, although I’m not certain, that this book may have been my introduction to both Agatha Christie and her famed Belgian detective, M. Hercule Poirot. The timing is right — 1956 was about the time I signed up with the Dollar Mystery Guild — but it’s also over 60 years ago, and who remembers for sure? I know I’ve read the book before, that much I’m positive of, but when? Only the vaguest of memories.

In this one Poirot is asked by his good friend and very successful mystery writer Ariadne Oliver to help her with a murder hunt she’s putting on, complete with victim and clues.

Asking him to pose as the person awarding the top prize to the winner of the contest, what she really wants Poirot to do is tell her why she feels so strangely that something is wrong, that somehow she is not in control of things.

Poirot is out of his depth. He deals with real murders, real suspects, real clues and real detective work, not fake ones. But it does give Ms. Christie to have some fun with the situation, and to allow the reader to have play along with her. She could wield a very wicked pen when she had the chance to do so, often at the expense of her characters, and so she does here.

But things eventually turn serious, as we knew it would all along. The young girl who’s playing the part of the victim is instead found really dead, and in the exact place the fake body was to be lying. This narrows the suspects down to only those who knew about Mrs. Oliver’s game ahead of time, ruling out all of the contestants who paid money to solve her make-believe mystery.

And of course what this means is that in the second half of the book it is Ms. Christie who’s playing a game with the reader. Only in retrospect, though, can it be said that this is a fair play mystery. The clues are there, but they’re obfuscated so well (or badly) that I challenge any reader to make sense of them before Poirot does.

I hope this does not sound like sour grapes. The sleight of hand, while extremely clever, could have been more sharply done this time, I thought, and the book would have been much better for it. My advice: Read this one very carefully, with the sense that what happens in every scene may be extremely important to the unraveling of the puzzle as it’s presented to you, and report back to me how well you do.

I don’t know if this last thought of mine deserves a PLOT WARNING or not, since I’m not sure whether it will help or not, but yes, the folly on Sir George Stubbs’s large estate does have a key role to play.

Wed 9 Nov 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Poirot Loses a Client. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1937. First published in the UK by Collins, 1937, as Dumb Witness. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback, including New Avon Library #10, 1945 (shown).

This one starts out in much the same way as the previous Hercule Poirot novel reviewed by me on this blog, Funerals Are Fatal; that is to say, by introducing in some detail a family with a wealthy matriarch (in this case) and (also in this case) a younger set, all of whom can use some money. Needless to say, for at least one of whom, sooner is far better than later.

Begun thus in similar fashion, the two books diverge from here. In Client, Poirot’s good friend, Captain Hastings is on hand to tell the tale, in first person. And Poirot is on hand much sooner, only 35 pages in. But not soon enough: the letter he receives from Emily Arundell, wishing to avail herself of his services, is too late. She has passed away, her death having occurred over two months earlier.

Reading between the lines of the letter, Poirot takes it upon himself to investigate. By all accounts, Miss Arundell died of natural causes, although there is the matter of the near fatal accident she had had a week or so before.

I think it helps to have Hastings along as a companion to Poirot on one of cases. Hastings is intelligent enough to tell the story carefully and well, with witty asides about incidents as they happen and the people they meet, but he’s not quite bright enough to put the facts together as swiftly as does M. Poirot. This is not an insult. Neither am I.

Part of Agatha Christie’s success is how easily she makes it seem to describe people and who they are in a minimum of words. This is what makes it possible for Poirot to solve the case by relying almost solely on the conversations he has with all of the people involved. Some of whom are suspects, others not, but they all have different perspectives on the facts, and all are useful in determining who the killer or killers may be.

Who this may be is revealed, in my opinion, too early, even before the family is gathered together for a final denouement. The solution is an anticlimax this time around, which is something not at all usual for Agatha Christie in my experience, but until then, there is plenty of story for the inveterate armchair detective to puzzle over. Those readers looking for lots of action, stay away.

Sun 11 Sep 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Funerals Are Fatal. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1953. First published in the UK as After the Funeral by Collins, hardcover, 1953. First paperback printing in the US: Pocket #1003, 1954. Reprinted many times. Film: MGM, 1963, as Murder at the Gallop.

Hercule Poirot’s self-proclaimed procedure in investigating a case is to study the people involved, listen to them (sometimes surreptitiously), and above all engage them in conversation. Talk to a murderer long enough, he believes, and he (or she) will say something, perhaps very innocuously, that will give himself (or herself) away.

And so it is in Funerals Are Fatal. It takes the full first chapter, a family tree and a Cast of Characters to identify all of the players firmly in the reader’s mind, but because each of the surviving members of the newly deceased Richard Abernathy’s family are such distinct individuals, as delineated so (seemingly) easily by Agatha Christie, it is not difficult to keep the various players straight from that point on.

Not that Poirot doesn’t rely on physical evidence as well, for he does, even going so far as to hire a private detective himself, a task absolutely necessary to check out alibis and so on — not Poirot’s forte at all.

The story. After Richard Abernathy’s funeral, his youngest sister Cora, a bit of an innocent, asks the question that perhaps the entire family (all in need of ready funds, it almost goes without saying) is also wondering: “But he was murdered, wasn’t he?”

When Cora is found murdered the next day, the family solicitor takes it upon himself to employ Poirot to make some discreet inquiries, and so he does, in a case in which everyone has a motive and (quite surprisingly) opportunity.

It is my firm opinion that anyone who claims that they can outwit Agatha Christie when it comes to solving the puzzles she put together when she was at the top of her game, as she is here, is — shall we say — exaggerating? Or very very lucky at guessing. (Maybe that is just sour grapes talking.)

Fri 15 Jul 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Murder at Christmas. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1939. Originally published in the UK as Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (Collins, hardcover, 1939). Reprinted many times, including under the title A Holiday for Murder.

What could be a better book to read on a flight from Detroit to Los Angeles than a beat-up copy of an good old-fashioned Hercule Poirot murder mystery? None I can think of, I say, and that it’s a locked room mystery is only icing on the cake.

And why murder at Christmas? Let M Poirot tell us:

“And families now, families who have been separated throughout the year assemble once more together. Now under these conditions, my friend, you must admit that there will occur a great amount of strain. People who do not feel amiable are putting great pressure on themselves to appear amiable!”

Dead with his throat cut is an old man who has been disappointed in his offspring and has told them just that only hours before. He also told them, with deliberate malice, that he intends to change his will immediately after Christmas. But does he live that long? You should know better than to ask.

Here’s the problem, though. The door to the dead man’s room is locked from the inside and must be broken down to get to him, and the windows do not open. The servants cannot have done it and there is no homicidal maniac on the loose anywhere around. It must be one of the family, but which one? And how?

Poirot claims the solution must come from the personalities of each of the possible suspects, and even more importantly that of the victim himself. How true! Any reader who dares to ignore such a challenge to the reader will make absolutely no headway in solving this case before Poirot does, and even then, only those readers who are already familiar with the tricks that Agatha Christie invariably had up her sleeve will stand a chance. As for myself, I have given up trying. To my mind, this is an amazing piece of work.

One thing still puzzles me though. The story does take place over the course of seven days between December 22nd through the 28th, but besides the gathering together of the old man’s sons and their wives, plus a surprise guest or two, there are no festivities planned, no grand meals, no decorations, no gifts, no snow, none of the usual Yuletide trappings. The story is fine without them, but I kind of missed them.

Sun 29 Nov 2015

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Sad Cypress. Dell #529, paperback, mapback edition, 1951. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1940; 1st published in the US by Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted many times since.

Agatha Christie tries her hand at romance in this one, more than usual, I believe, and while it’s still a detective story that sucks the reader right in, I don’t think that it’s one of her better ones.

Accused of killing the young girl who stole her fiancé away from her, unknowingly so, Elinor Carlisle in the story’s prologue is on trial for her murder. The girl was poisoned, and even Hercule Poirot concedes that on the face of the evidence, there is no one else who could have done it.

Act One of the story is a flashback to a time well before the murder. Other than a cameo appearance in the prologue, Poirot does not show up until the book is half over. Although the local doctor who engages his services only wishes to prove Elinor innocent, Poirot demurs, saying he must only go where the facts take him.

The second half of the book is then split into two parts. First, the eccentric Belgian detective questions everyone who has any connection with case. Then follows Elinor Carlisle’s trial, and then and only then, when the defense has its turn, are the Poirot’s deductions that revealed.

Wills (or in one case, the lack thereof) are important in this tale, and of course there is the matter of the poison that is used, one of Christie’s favorite devices for removing certain people from her stories. It is easy to spot some of the red herrings for what they are, while the matter of parentage comes also into play, and at the end Poirot explains how he knew that everyone involved in the case told at least one lie to him.

While the explanation at the end almost holds up, I think the solution has more than one loose end to it. How could the killer get away with it, you ask (or least I did), and why didn’t Poirot trust the police to catch that killer before he/she makes his/her escape, instead leaving the the defense to provide the evidence in court. The trial is a charade, in other words, designed by the author only for its dramatic effect, which as in all of Agatha Christie’s novels, is considerable.

Christie is as readable as always in Sad Cypress (the title coming from a passage in Shakespeare), but the story is just a little too complicated this time, and for me, not satisfactorily so.

Sun 19 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

AGATHA CHRISTIE – The Boomerang Clue. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1935. First published in the UK as Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? Collins, hardcover, 1934. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback, including Dell #46, mapback edition, no date [1944]. TV movie: London Weekend Television, 1980 (Francesca Annis & James Warwick). TV movie: ITV, 2009 (an episode of Agatha Christie’s Marple).

Don’t get the wrong idea about that last TV series adaptation. This is not a Miss Marple mystery, and not only was a very loud outcry about shoehorning a character into the story who didn’t belong there, but also how they badly botched the story line itself, or so I’ve read.

I’ve not seen this particular Marple adaptation, but (speaking generally) if there’s a perfectly fine story line that you’re working from, why mess around with it? Perhaps the producers thought that people watching their adaptation had never read the book. Perhaps the plan was to pull the rug out from under the feet of those who had, to give them a “surprise” ending.

But do you know, it doesn’t really matter. We’ll always have the book, and it’s a good one. I don’t know why, but I’m always surprised to pick up an Agatha Christie novel and discover all over again how readable she is. I started this one rather late at night, thinking to read a chapter or so, and an hour later I’d finished ten. Chapters, that is. It isn’t easy to write stories that read as easily as this, but it has to be one of the reasons Christie’s books are still in bookstores today and 99.9% of her contemporaries are not.

This one begins with a young Bobby Jones (not the famous one) hitting a golf ball and doing dreadfully at it, trying mightily several swings in succession, but hearing a cry, discovers a dying man lying at the bottom of cliff. He had fallen perhaps, as Bobby and his golfing partner believe, not to mention the police and the coroner’s jury, but we the reader know better.

Before he dies, though, the man utters a dying question: “Why didn’t they ask Evans?” We are at page 9 and the end of Chapter One, and anyone who can stop here is a better person than I.

Assisting Bobby in his quest for the truth, especially after surviving being poisoned by eight grains of morphia, is his childhood friend, Lady Frances Derwent, whom he calls Frankie. Together they make a great pair of amateur detectives, continuing to investigate the case even after the authorities have written the man’s death off as an accident.

The tone is light and witty, as if investigating a murder is a lark, but this intrepid pair of detectives do an excellent job of it, even to the extent of faking an automobile accident and inserting an “invalid” Frankie into their primary suspect’s home.

Before continuing, I’ll stop a moment here and point out that Bobby is the son of a vicar and a former Naval officer, while Frankie’s father is a Lord and extremely wealthy. The difference in social standing means little to Frankie, all but oblivious to her wealth, but it does to Bobby, who finds himself more and more infatuated with the young beautiful wife of a doctor they suspect is behind the plot, to Frankie’s displeasure, although the woman may be the man’s next victim herself. (This does not mean that Frankie is averse to using her position in life to help their investigation along.)

The tone does get darker as Bobby and Frankie close in on the killer, and at the same time, the threads of the plot get more and more complicated. I’d have rather the story stay focused on the detection, but toward the end it becomes more and more a thriller. It couldn’t be helped. The essential clue is there all of the time, but nothing could be deduced from it until the book has only 15 pages to go, but making the renamed US title at lat make sense.

In summary, here’s a book that’s immensely fun to read, with a delightful couple doing the honors in investigating a crime the police do not even realize was a crime, dreaming up various scenarios and coming up with sundry plots to incriminate the killer. Coincidences abound, but who cares?

Tue 24 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Authors[6] Comments

A SHORT NOTE ON AGATHA CHRISTIE’S PROFESSIONALISM

by Josef Hoffmann

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu claimed that a literary field began to form in 19th century society that followed specific rules. These rules had to be obeyed by a writer if he wanted his literary products to be successful. Indeed, he almost had to internalise them.

For example, an author of fiction must not directly express his political or philosophical views, as an author of factual books might, but must instead translate them into the narrative of a novel, integrated into the plot or the dialogues of the protagonists, in order to comply with the rules of novel-writing. Yet the rules of the literary field are not rigid, but are adaptable to some degree, thus allowing scope for experimentation.

It is my theory that, at the time when Agatha Christie began to write her detective novels, a relatively independent literary field began to develop – the genre of the detective story – with its own specific rules. This was expressed in the discourse of the time on the rules of fair play between author and reader and the foundation of the Detection Club, which obliged its members to comply with certain rules.

Agatha Christie was so successful because she mastered the rules of the genre (which were not as narrowly defined as those of the Detection Club), rules that became second nature to her.

This becomes clear, for example, in her Miss Marple novel, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930). Almost at the beginning of the detective novel, Christie writes that the life of the parish seems to have been created for the amusement of the vicar’s young wife, and that her regular afternoon teas served the purpose of exchanging gossip. Towards the end of the novel, the vicar gives a sermon which, rather than being shaped by the Christian spirit, foams with dramatic rhetoric in order to impress the congregation.

Despite this interweaving of criticism of the church, it would never have occurred to Christie to call her novel something like “The Church Is Dead.†Instead she chose a suitable title for a detective novel, The Murder at the Vicarage, which itself is actually outrageous, as the vicarage, the centre of the Christian parish, should be a place of devotion and the love of one’s fellow man, and not the scene of a murder.

But this is accepted by the reader, whereas a title explicitly critical of the church would have met with rejection. In Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938), there is a murder during this festive season, despite the fact that, in the opinion of one protagonist, Christmas should be a celebration of peace and reconciliation.

But Hercule Poirot calls Christmas a time of hypocrisy. Yet the title of the detective novel is not “A Celebration of Hypocrisy,†which would certainly have damaged the sales of the book.

In his history of crime literature, Julian Symons finds fault with the fact that the General Strike of 1926 never took place in British detective stories of the Golden Age. But that is not quite right. Christie included the element of the General Strike in the narrative structure of the novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, from 1926. By making the narrator and assistant to the detective a murderer, she suspended the rules of fair play, quite in the manner of a general strike.

The scope of Agatha Christie’s knowledge was broader than some literary critics would like to believe.

Further Reading:

Pierre Bourdieu: The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, Polity Press 1996

John Curran: Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, Harper 2011

Curtis Evans: Was Corinne’s Murder Clued?: The Detection Club and Fair Play, 1930-1953, CADS Supplement Number 14

Howard Haycraft (ed.): The Art of the Mystery Story, Carroll & Graf 1992 (Part 2: The Rules of the Game)

Julian Symons: Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel: a History, Papermac 1992.

— Translated by Carolyn Kelly

Mon 14 Apr 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

AGATHA CHRISTIE – The Man in the Brown Suit. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1924. First published by John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1924. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and soft. First serialised in the London Evening News under the title Anne the Adventurous, 29 November 1923 to 28 January 1924 (50 installments). TV Movie: CBS, 1988, with Stephanie Zimbalist (Anne Beddingfeld), Rue McClanahan, Tony Randall, Edward Woodward (Sir Eustace Pedler), Ken Howard (Gordon Race).

While I am tempted to say that this is something of a departure by Christie, that would merely demonstrate my ignorance, as this is one of her earlier works.

Here she has written a thriller featuring an intelligent, on all but a few occasions, young lady who is seeking adventure. When Anne Beddingfield observes a supposed accidental death at a tube station and suspicious behavior by an alleged doctor, she connects this with a murder the same day. Soon she is spending her meager inheritance for a berth on the Kilmorden Castle, en route to South Africa, in pursuit of the alleged murderer, the Man in the Brown Suit.

Developments are revealed through the viewpoints of Beddingfield and Sir Eustace Pedler, M.P., both drolly and sillily, if there is such a word. Good fun and, incidentally, a forerunner to…

But you don’t want to know that, do you? I had that knowledge when I started the novel, and it didn’t spoil the pleasure. Other people may be less complaisant.

— From

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Tue 29 Jan 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[13] Comments

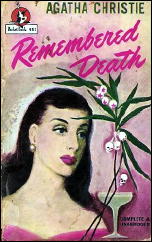

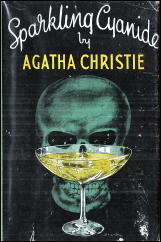

AGATHA CHRISTIE – Remembered Death. Dodd Mead, hardcover, February 1945. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including Pocket 451, 1947 and Cardinal C-312, April 1958 (the copy at hand). First published in the UK as Sparkling Cyanide (Collins, hardcover, 1945).

So, how long’s it been since you read a Christie? For me, it’s been a while. A good long while, and much longer than it should have been. Several years at least. I read most of the Agatha Christie’s work when I was in my teens, along with all but one of the Ellery Queen’s – I was not going to go and spoil The French Powder Mystery by reading it. I was going to save it and read (and relish) it later. And later has come (but not gone, by golly) and I still haven’t read it. My oh my oh my.

But I read all of the Poirot’s and all of the Miss Marple’s, all of them that had been written while I was still in my teens, and if you were to give me one now, and ask me, Who did it? I couldn’t tell you, except for one, and it was one of Poirot’s.

But I never read this one. I don’t remember this one at all, and maybe it’s because M. Poirot is not in it, nor Miss Marple. It’s Colonel Race who’s in this one, the last of four of Christie’s mysteries he was in – the others being The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), Cards on the Table (1936) and Death on the Nile (1937), the latter two being primarily cases for Poirot. Race is only a friend of the family in this one, not the detective of record – that being Chief Inspector Kemp – but he is instrumental at least in part in bringing the culprit(s) to justice.

And quite a mystery it is that has to be solved. The young wife of an older man supposedly committed suicide one year before this story begins. By suicide, in a restaurant while celebrating her birthday. Depression caused by illness is the verdict, because there was no feasible way (apparently) that anyone could have gotten the cyanide into her champagne.

But the widower has been getting anonymous messages that hint that Rosemary was murdered, and indeed everyone who was at the table with her when she died could have had a motive. George Barton concocts a plan, the kind that exist only in mystery stories, one imagines, and that is to bring everyone back who attended the first party, and have another party at the same place, the same time, but a year later.

You have read Agatha Christie before yourself, haven’t you? Disaster happens. If this is a cozy, it’s a cozy with a sharp, wicked edge to it.

Nor is all what it seems, as I probably needn’t warn you, and as an “impossible crime,†which this very nearly is, it’s one that just might, maybe, work. And not too many readers are going to outwit Ms. Christie, and maybe that’s why, of all of the many, many practitioners of mysteries from the Golden Age, Christie is the only one whose books you will find on the shelves in Borders, Waldens or Barnes & Noble today.

And not only is Christie a master of deception, she has an exceeding observant eye when it comes to people, and she can take what she sees and convert it into words. (I notice that I’m using the present tense. I think that’s because I sense that as long as her books are alive, so is she.)

With just a bit of a dialogue of one of characters, she can match him perfectly to her description of him later. George Barton is talking to his wife’s younger sister on page 17, and a few lines later Iris thinks of him to herself as “kind, awkward, bumbling.†And he was. Exactly. A stereotype, perhaps, but even stereotypes are based on reality.

And what I understand now, at this late date in my mystery reading career, is that it’s Christie’s keen eye into character that makes her mysteries work, with all of the intricate machinations inherent thereto, and somehow I don’t think I realized that back when I was reading her books for the first time. Back then it was the cleverness of the plot, and that aspect only, not thinking, or caring, that it’s that way that people act and react that’s equally essential, if not – dare I say it? – more so.

[UPDATE] 01-29-13. A couple of things have happened since I wrote this review. You may choose which is the more significant. Both Borders and Waldens are out of business. And I have, at long last, read The French Powder Mystery. You may read my review here.

Sat 26 May 2012

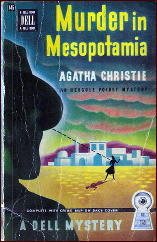

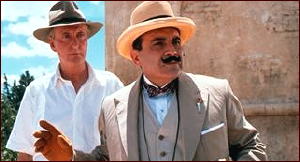

“Murder in Mesopotamia.†An episode of Agatha Christie’s Poirot. ITV, UK, 8 July 2001. (Season 8, Episode 2.) David Suchet (Hercule Poirot), Hugh Fraser (Captain Hastings), Ron Berglas, Barbara Barnes, Dinah Stabb, Georgina Sowerby, Jeremy Turner-Welch, Pandora Clifford, Christopher Hunter, Christopher Bowen, Iain Mitchell. Based on the novel by Agatha Christie (1936). Dramatized by Clive Exton. Director: Tom Clegg.

In this film Agatha Christie’s famed Belgian detective Hercule Poirot is in what is known as Iraq today, visiting an archaeological dig, and so is his good friend Captain Hastings, although he was not in the novel. In the book the story was largely told from the point of view of Nurse Leatheran (Georgina Sowerby), but in this made-for-TV adaptation her role has been cut down considerably.

There are a few other relatively minor changes and enhancements, but for the better, I can’t swear to it. The nurse’s patient, the new wife of the expedition’s leader, is the primary victim.

She is found dead in her room beside her bed, having been hit in the head by the old stand-by, a blunt instrument. Strangely, though, the window is locked and the only access to her room was a door that was under watch at all times.

The exterior scenes were filmed in Tunisia, a very worthy stand-in for that other war-torn part of the world, and are beautifully done, if not out-and-out stunning. Suchet, as usual, is the pitch perfect Poirot, and all of the other players play their roles with distinction.

The problem is, and I really do hate to say that there are problems, but for a film that is less than two hours long, there are simply too many characters involved. There were a couple of them I did not even recognize in the final “let’s gather all of the suspects together and I will name the killer†scene.

A second viewing would also help in putting together the various scenes that took place both before and after the murder, many of them too brief to make sense at the time – but of course they are needed to fill in the details as Poirot begins his final re-creation of the crime before his enraptured audience.

The puzzle of the “locked room†is very cleverly done, however, which makes watching this movie worthwhile, even in the face of a motive (and how it came about) that seems quite unbelievable to me. Perhaps Agatha Christie made a better job of it in the book, but checking Robert Barnard in A Talent to Deceive, he agrees with me: “Marred by an ending which goes beyond the improbable to the inconceivable.â€

This episode is available on DVD, and at the moment, it can be seen in several parts on YouTube.