Search Results for 'Anthony Gilbert'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 22 Mar 2017

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE LAST TRAIN FROM MADRID. Paramount Pictures, 1937. Dorothy Lamour, Lew Ayres, Gilbert Roland, Karen Morley, Lionel Atwill, Helen Mack, Robert Cummings, Olympe Bradna, Anthony Quinn, Lee Bowman. Director: James P. Hogan.

Finally the train. Close to an hour into a movie with a running time just under ninety minutes, the audience finally gets to see the titular train. That’s pretty much my first and greatest impression of this rather slow moving and melodramatic movie about a disparate group of people attempting to obtain passes for the last train out of Madrid during the Spanish Civil War.

There are a few subplots involving romance during wartime, and how a lifelong bond of friendship takes precedence over political affiliations. But overall, the film is a rather talky affair, all leading up to the final sequence in which some of the main characters finally do end up on a train for Valencia.

What The Last Train from Madrid does have going for it is its exceptional cast. Gilbert Roland, in particular, is always a delight to see on screen. And, love him or hate him, there’s no denying that Lionel Atwill is a distinct presence in any movie that he appears in. (Although, Atwill as a Spanish Army officer? Not believable.)

On the other hand, a young Anthony Quinn and an even younger looking Robert Cummings are quite convincing as Spanish soldiers.

It’s just unfortunate that, with a cast like this, there isn’t enough action in this stagey production to keep the viewer particularly engaged throughout the proceedings.

Wed 30 Mar 2016

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I can’t claim to have read all 70-odd Maigret novels, but I’ve been reading them off-and-on since my teens and I still find many of them fascinating, especially the ones from the Thirties. Unfortunately my French isn’t good enough to allow me to read them as Simenon wrote them, but over the years I’ve sometimes wound up with two different translations of the same book, and a number of them are now being translated yet a third time. Reading two translations side by side is a heady experience, especially if you put on your detective cap and try to figure out what is and what isn’t in the original.

There were characters a bit like Maigret and characters actually going by that name in a few of the more than 200 pulp novels Simenon wrote under a dozen or so pseudonyms in the 1920s, but the first genuine Maigret was PIETR-LE-LETTON, which was written in 1929 and published by A. Fayard et cie two years later as either the third or the fifth in the monthly Maigret series. In the States, as THE STRANGE CASE OF PETER THE LETT (1933), it was the fourth of six early Maigrets published by the Covici Friede firm.

I am lucky enough to have a copy of that edition. No translator is credited but various sources in print and online claim that Simenon’s French was first rendered into English by Anthony Abbot. As all lovers of detection know, Abbot was the name under which best-selling novelist Fulton Oursler (1893-1952), following the lead of S. S. Van Dine, both signed and narrated the cases of New York City police commissioner Thatcher Colt, published originally by Covici Friede.

Many decades ago I read all the Abbot novels and wrote an essay about them which in its final form can be found in my CORNUCOPIA OF CRIME (2010). I had heard the rumor that Oursler had translated the early Maigrets but, since he had died when I was a child, I couldn’t ask him. I did however write his son Will Oursler (1913-1985), who was also a part-time mystery writer both under his own name and as Gale Gallagher and Nick Marino.

In a letter dated January 4, 1970 — My God! More than 46 years ago! — he replied as follows: “[M]y father did not make the actual translation as he simply was not that fluent in French. It is more probable that most of his effort was in the area of editing and polishing after the translation was done. It is certain that he would not have been capable of translating six Maigret novels.â€

The second translation of PIETR-LE-LETTON, retitled MAIGRET AND THE ENIGMATIC LETT, was by Daphne Woodward, published in 1963 as a Penguin paperback and sold in the U.S. for 65 cents. According to Steve Trussel’s priceless Maigret website, the Woodward version “is much closer to Simenon’s French text, the first being wayward at times.â€

Even without the French text at hand, I’ve found indications that Trussel is right. The novel features an American millionaire staying in the posh Hotel Majestic who is strangely connected with Pietr. The 1933 translation gives his name as Mortimer Livingston, which seems perfectly proper for the character. Daphne Woodward renders the name as Mortimer-Levingston, which is silly but consistent with the young Simenon’s ignorance of all things American.

This character has a secretary, staying in London but never seen or spoken to. His name in the 1933 translation is Stone, which sounds fine. In Woodward’s rendition he’s called Stones, which is dreadful but again consistent with Simenon’s ignorance. It seems clear that the anonymous original translator went out of his or her way to Americanize various details in the novel that Simenon flubbed. Or was that part of the polishing job by Fulton Oursler?

Written before Maigret and his world had crystallized in Simenon’s creative mind, PIETR-LE-LETTON is significantly different from almost all the later novels in the series. For one thing, it’s much more violent, with a total of four murders (the work of three different murderers) plus a suicide, committed in Maigret’s presence and with his gun.

There’s also a great deal more physical action, with Maigret racing from Paris to the Normandy fishing port of F camp and out over the rocks along the muddy seacoast after his chief adversary despite being half-frozen and having been shot in the chest! But there’s a genuine battle of nerves between Maigret and his quarry, more intense and existential than their counterparts in many later books in the series, and the evocation of atmosphere which was Simenon’s trademark is as powerful as in the finest films noir. In either translation this debut novel is a gem.

In 2014 Penguin Classics released yet another translation, this one by David Bellos and bearing the title PETER THE LATVIAN. Did some political correctness guru decide that Lett was a demeaning term like Polack? And what did Bellos make of passages like the beginning of Chapter 13? In Woodward’s version: “Every race has its own smell, loathed by other races…. In Anna Gorskin’s room you could cut it with a knife…. Flaccid sausages of a repulsive shade of pink, thickly speckled with garlic. A plate with some fried fish floating in a sour liquid.â€

There’s nothing like that first sentence in the 1933 rendition, perhaps because Fulton Oursler cut it out, but we do get to see and smell the “horrible pink sausages, flabby to the touch and filled with garlic†and “a platter containing the remains of a fried fish swimming in a sour-smelling sauce….†Need I mention that this scene takes place in the rue du Roi-de-Sicile, in Paris’s Jewish ghetto?

While fine-tuning this month’s column I discovered that there really was, or at least might have been, a Latvian criminal named Pietr. He was known as Peter the Painter and his real name may have been Pietr Piatkow, or perhaps Gederts Eliass or Janis Zhaklis. He seems to have emigrated from East Europe to London where he joined an ethnic gang that stole in order to fund their radical political activities.

He is believed to have taken part in the infamous Siege of Sidney Street which inspired the climax of Hitchcock’s THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934), although a brief sketch in England’s Dictionary of National Biography warns us that “None of the … biographical ‘facts’ about him … is altogether reliable.â€

Whether Simenon had ever heard of this man remains unknown, but in any event the fictional Pietr the Lett is not a leftist radical, does not commit crimes of violence and turns out not even to be Latvian. Which raises another mystery: Why did Simenon call the guy Pietr the Lett? Pietr the Estonian — or the Esty? — would have sounded ridiculous even in French, but there’s absolutely no reason in the novel why he couldn’t have been a genuine Latvian. Ah well, c’est la vie.

Train murders were something of a Simenon specialty. Of course, when such a crime takes place in a Maigret, it’s bound to lose intensity and vividness simply because we can’t be there to witness it. This is certainly true of the first murder in PIETR-LE-LETTON, and it’s also true of a Maigret short story dating from about seven years later.

We learn from Steve Trussel’s website that “Jeumont, 51 minutes d’arrêt!†was written in October 1936 and, along with more than a dozen other shorts from the same period, was first collected in France as LES NOUVELLES ENQU TES DE MAIGRET (1944). It was never included in any collection of Maigret shorts published in English but did appear in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, November 1966, as “Inspector Maigret Deduces,†with no translator credit and with an unaccountable 1961 copyright date.

(The FictionMags Index explains the date — the story’s first appearance in English was in the UK edition of Argosy for October 1961—and identifies the translator as one J.E. Malcolm.)

As in PIETR-LE-LETTON, Maigret tackles a murder on a train, this one bound from Warsaw to Berlin to Liège in Belgium (Simenon’s birthplace) to Erquelinnes (on the Belgian side of the border with France) to Jeumont (just across the line on the French side) and on to Paris, except that one of the six passengers in a particular compartment is found dead in his seat at Jeumont. The dead man is a wealthy German banker named Otto Bauer.

Called in by his railroad-detective nephew, Maigret gets in touch with his Berlin counterparts and learns that Bauer was forced out of the banking business “after the National Socialist revolution, but gave an undertaking of loyalty to the Government, and has never been disturbed….†and also that he’s “[c]ontributed one million marks to party funds.â€

Clearly, despite his name, Bauer was a Jew, and was desperately trying to escape Nazi Germany with whatever money he could salvage. That element is what makes this tale unique among the Maigret stories of the late Thirties. At least in translation there’s not a word of sympathy for the victim, not a word of disgust for the regime he was fleeing. For Maigret, and for Simenon I fear, it’s just another factor in another case. The murder weapon, by the way, turns out to be a needle, which was also one of the murder weapons in PIETR-LE-LETTON although not the one used in the train killing.

I wouldn’t venture to guess how many train murders can be found in Simenon’s stand-alone novels, but the most vivid and intense that I can recall takes place in Chapter 2 of LE LOCATAIRE (1934; translated by Stuart Gilbert as THE LODGER in the two-in-one volume ESCAPE IN VAIN, 1943). Elie Nagear, a desperate young Turkish Jew, bludgeons to death a wealthy Dutch entrepreneur with whom he’s sharing a couchette on the night train from Brussels to Paris after it crosses the French border. (In European trains of the Thirties a couchette was a small chamber used as sleeping quarters by two and sometimes four total strangers.) On the run from the police, he takes a train back to Belgium and holes up in a boarding house for foreign students in the city of Charleroi.

In Chapter 9 there’s a brief conversation between Elie and a fellow roomer. “They were talking in the papers of the difference between French and Belgian law. Well, suppose someone who’s being proceeded against in Belgium by the French police commits a crime in Brussels, or some other Belgian town…. What I mean is, that a man who’s liable to the death penalty in France might happen to commit a crime in Belgium. In that case, it seems to follow that he should first be tried in Belgium, if it’s in that country he’s arrested. And it also follows, doesn’t it, that he should serve his sentence in that country?â€

What Simenon assumes his readers know is that France at this time still had the death penalty while Belgium had abolished it. On May 10, 1933, in Boullay-les-Trous, a village south of Paris, an obese pornographer named Hyacinthe Danse, who was known to Simenon, murdered both his mother and his mistress. Fearing that he’d be caught and guillotined, Danse took the train to Liège in Belgium, where on May 12 he murdered his childhood confessor (and also Simenon’s), a Jesuit priest named Hault, and then turned himself in.

This case was apparently still pending in Belgium when Simenon wrote LE LOCATAIRE. Sure enough, in December 1934 Danse was convicted of Hault’s murder and sentenced to life imprisonment, meaning that he couldn’t be extradited to France and stand trial for the other murders until he was dead. Less than two years later, Simenon turned the Danse story into a short Maigret, included as “Death Penalty†in the collection MAIGRET’S PIPE (1977) and discussed in my column for September 2015.

Which is enough journey to France for one month. Or, as they say on the left bank of the Seine: basta.

Thu 30 Jul 2015

THE AVENGERS BEFORE DIANA RIGG –

PART ONE: THE BEGINNINGS

by Michael Shonk.

THE AVENGERS, Seasons 1-2. ABC, (Associated British Corporation) Production for ITV, 1961-63. Patrick Macnee as John Steed (Seasons 1 and 2), Ian Hendry as Dr. David Keel (Season 1), Ingrid Hafner as Carol Wilson (Season 1), Julie Stevens as Venus Smith (Season 2), and Jon Rollason as Dr. Martin King (Season 2). Theme composed and performed by Johnny Dankworth. Produced by Leonard White (Seasons 1and 2), John Bryce (Season 2).

The recent death of Patrick Macnee had me and anyone else who has watched TV in the last fifty years thinking about The Avengers. Most fans of the series, especially Americans, are familiar with Emma Peel and the later seasons of The Avengers, but not the early seasons. I have always been curious on what happened before Diana Rigg arrived.

It began with the failed British TV series Police Surgeon that starred the popular and talented actor Ian Hendry as Dr. Geoffrey Brent. ABC was looking for something different from the “realistic and gloomy plays†that currently filled the schedule. Originally plans were to spin-off the character Dr. Brent but for a variety of reasons it was decided to drop any connection the new series might have to Police Surgeon. ABC’s head of programming Sydney Newman and Police Surgeon producer Leonard White decided to create a new series around Ian Hendry. Newman, White and a group of production people and writers would create The Avengers, a hardboiled thriller with a dark sense of humor that starred Hendry as Dr. David Keel. Patrick Macnee was hired as spy John Steed in a supporting role. The only other connection The Avengers had to Police Surgeon was actress Ingrid Hafner who played Police Surgeon Nurse Amanda Gibbs and The Avengers Nurse Carol Wilson.

For years the episode “The Frighteners†was the only surviving episode from the first season (or in British terms the first series), but then the episode “Girl On the Trapeze†and the first act of the first episode “Hot Snow†were found in the UCLA TV/Film archive. It is not unusual now to find all three on YouTube in various conditions.

Despite the lack of actual episodes, today we know much more about the first season. Reconstructions of the missing programs can be found at Alan Hayes’ website “The Avengers Declassified.â€

There is also a book The Strange Case of the Missing Episodes – The Lost Stories of The Avengers, Series 1, by Richard McGinlay, Alan Hayes and Alys Hayes (Hidden Tiger, 2013) that examines each of the Season One episodes in detail. Another book by McGinlay and Alan Hayes, With Umbrella, Scotch and Cigarettes – An Unauthorized Guide to The Avengers Series 1 (Hidden Tiger, 2014) examines behind the scenes of the first season. (I highly recommend both books, especially With Umbrella… for more details about the series than I can fit in here.)

Also beloved audio producer Big Finish has begun to record audio recreations of the lost Season One episodes with Anthony Howell as Dr. Keel, Julian Wadham as John Steed and Lucy Briggs-Owen as Carol Wilson.

The series first three seasons were shot live on videotape and in black and white. Because of a lack of worthy scripts and to gain more time Season One episode three was broadcast live and that would continue until episode ten returned to live on videotape.

Because of the regional system of British TV, the actual airdates vary such as the first episode “Hot Snow†first aired in only two small regions (Midlands and North) on January 7, 1961 then in five other regions including London on March 18, 1961 and not transmitted at all in the final five regions. Because of this I have left the airdate off the episodes reviewed below.

One note about the YouTube videos used here. Each is the best available at the moment, but the videos are marred by the unnecessary addition of a iris shape light in the center of the picture that was pointlessly added by whoever downloaded these episodes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8_CacBKW6zQ

“The Frighteners.†– Teleplay by Berkeley* Mather. Directed by Peter Hammond. Produced by Leonard White. Guest Cast: Willoughby Goddard, Philip Gilbert and Philip Locke. *** A rich father hires the Deacon and his “frighteners†to beat-up and scare off a man who wants to marry his daughter.

* On-screen typo for Berkely Mather (author of Pass Beyond Kashmir (1960). The book almost adapted for film by Bond producers to star Sean Connery and Honor Blackman.)

It is impossible to fairly critique this early episode after experiencing what would follow. Those who enjoy their crime melodrama’s hardboiled will enjoy this one. Ian Hendry turned in a fine performance as the reckless heroic Doctor Keel. But the series and Steed were still a work in progress. While Hendry was the star and the story focused on his character he was just one of many to assist the ruthless and flippant Steed. Perhaps the most noticeable difference between this The Avengers and those with Rigg was a lack of playfulness and fun.

The first season of The Avengers was a mild success but was cut short by an Equity (actors) strike at ITV that began November 1961 and lasted until April 1962. Only twenty-six episodes were completed when the strike shut down production. Producer Leonard White and the writing staff continued to work on possible changes to the series. White had hoped to do thirty-nine episodes for the first season. In late 1961 White began to make plans to add a new female character to the cast, a jazz singer named Venus Smith. She and Dr. Keel would alternate episodes as Steed’s partner.

As some point Ian Hendry broke his contract and left the series. Producer White would long hold out hope that Hendry might return if only for an occasional guest role.

In February 1962 while the actors were still on strike, White briefed the writers about Season Two and its characters – John Steed as the lead, Venus Smith and Cathy Gale as his partners who would alternated episodes, and One-Ten (one of the men to give Steed his instructions – played by Douglas Muir in five episodes).

The strike ended in April and The Avengers resumed production in May, despite not having yet cast the roles of Cathy Gale (Honor Blackman would get the part in June 1962) or Venus Smith. The first audition for the role of Venus was held in August 1962 and Angela Douglas (Carry On… film series) was hired. But then for some reason she was no longer available. A second audition was held August 31, 1962 and Julie Stevens was selected for the role of Venus Smith. But Steed needed some one to be his partner to resume shooting in May, and despite his hopes producer White finally realized Ian Hendry was not coming back.

Enter Dr. Martin King played by Jon Rollason. An obvious fill-in for Ian Hendry who was now off making movies, Rollason lacked the talent and wit of Hendry. He lasted only three episodes – “Mission To Montreal,†“Dead On Course,†and “The Sell-Out.†All three episodes made use of first season scripts written for Hendry’s Dr. David Keel, “Mission To Montreal†was originally “Gale Force,†“Dead On Course†was “The Plane Wreckers,†while “Sell-Out†kept its original title. Little was changed except the characters’ names with Dr. David Keel becoming Dr. Martin King and Keel’s Nurse Carol Wilson (Ingrid Hafner) replaced by Judy (played by Gillian Muir).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zuiZBJPzGH8

“Mission To Montreal.†Teleplay by Lester Powell. Directed by Don Leaver. Produced by Leonard White. Guest Cast: Patricia English, Iris Russell, and Mark Eden. *** When a sex-symbol star’s stand-in is killed in her dressing room the terrified actress quits and takes a cruise to Montreal.

The episode was an average TV thriller about a cruise ship full of spies and various suspicious characters. While Rollason is instantly forgettable in the leading role, Macnee continued to make the callous Steed almost likable.

Poor Julie Stevens. She had a nice voice but lacked a great deal as a performer and actress. It was not her fault the writers failed so epically with the character of Venus Smith.

The idea of adding a jazz singer with the backdrop of the shady wicked world of the nightclub seemed to fit Steed’s work and the naughty second season. The additional music could enhance the current and popular soundtrack work of Johnny Dankworth. It would also allow more sexual situations, something both Newman and White wanted to add in the second season. Yet somehow they went from casting a CARRY ON girl as Venus Smith to inexperienced young Julie Stevens. Venus became a naïve not too bright twenty-year old – an anti-Mrs. Catherine Gale.

The writers seemed lost what to do with Venus. She seemed to exist to get in the way and need rescued. There are episodes when we wonder why Venus is even there. In “A Chorus of Frogs,†Steed involves Venus in a dangerous mission without asking just so he would have a cabin to stay in when he stows away on a ship. The Steed-Venus relationship is as creepy as Steed would ever get as he flirts with her then ruthlessly toss the clueless young girl into situations that could cost Venus her life.

Thankfully for all, Venus lasted only six episodes in the second season -“The Decapod,†“The Removal Man,†“Box of Tricks,†School of Traitors,†“Man In the Mirror,†and “A Chorus of Frogs.â€

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlI_V0XigtU

“The Removal Man.†Teleplay by Roger Marshall and Jeremy Scott. Directed by Don Leaver. Produced by Leonard White. Guest Cast: Edwin Richfield, Patricia Denys, George Roderick and The David Lee Trio (David Lee: piano, Spike Heatley: double bass, and Art Morgan: drums). Recurring Cast: Douglas Muir as One-Ten. *** Steed goes undercover to stop a gang of hired killers with high profile targets. One-Ten and Steed have arranged to have the unsuspecting Venus get hired to sing at one of the gang member’s nightclub.

An above average hardboiled thriller with logic problems and an unlikable Steed. There is no real reason for Venus to be there except to sing and to have someone there to ruin undercover Steed’s plan. This episode is a good sample of the increased kinkiness of the second season with hints of nudity and sexual banter. The nightclub setting was underused and the music for the most part seemed to be filler for a too short script.

Venus’s music numbers were: “An Occasional Man†(by Ralph Blane and Hugh Martin – originally for the film Girl Rush, 1955), “I May Be Wrong “ (by Henry Sullivan and Henry Ruskin, 1929) and “Sing For Your Supper†(by Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart – originally for stage play “The Boys of Syracuse,†1938).

David K. Smith’s website “Avengers Forever” has a cheeky essay from this episode co-writer Roger Marshall about writing for The Avengers and some of his co-workers such as Brian Clemens.

Producer Leonard White would leave the series during Season Two. Replacing White was John Bryce, one of the series story editors from the beginning. Executive Sydney Newman left to run BBC programming and help create Doctor Who and Adam Adamant Lives!

Steed’s third and main partner in Season Two would save the series. Next we will examine the story of Mrs. Catherine Gale as played by Honor Blackman.

Sat 4 Apr 2015

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I own very few European crime novels in both their original language and in English, but one of those is Der Richter und Sein Henker or, as it’s known over here, The Judge and His Hangman (1952; U.S. edition 1955), the first novel of Swiss playwright Friedrich Duerrenmatt (1921-1990).

I read it in both languages many years ago and again last month. It’s about Hans Bärlach (whose last name in English is missing the umlaut), Kommissär of the Swiss police, a man clearly near death, and his 40-year-long struggle against a sort of existential criminal who committed a motiveless murder in front of the Kommissär’s eyes and dared Bärlach to pin it on him.

More than sixty years after its first publication the book is still a compelling read, and the German edition (designed for students who are learning the language) adds several dimensions to what readers of the translation are offered, including two maps that make clear the relationship to each other of the various small towns near Bern where much of the story takes place.

Reading the German side by side with Therese Pol’s English version also reveals where Pol now and then goes her own way. At the end of Chapter 11 (Chapter 8 in the translation), the diabolical Gastmann breaks into Bärlach’s house beside the Aare River and steals the Kommissär’s file on him. “I’m sure you have no copies or photostats. I know you too well, you don’t operate that way.â€

A procedural this novel ain’t. He throws a knife at Bärlach, just missing him, and goes his way. “The old man crept about the room like a wounded animal, floundering across the rug on his hands and knees…, his body covered with a cold sweat.†He moans softly in German: “Was ist der Mensch? Was ist der Mensch?†This simply means “What is man? What is man?†but Therese Pol expands it to: “What sort of animal is man? What sort of animal?â€

That’s not too much of a stretch compared with the last chapter where Bärlach learns that his young assistant Tschanz “sei zwischen Ligerz und Twann unter seinem von Zug erfassten Wagen tot aufgefunden worden,†meaning that between two of the villages shown on the first map he was found dead under his car, which had been struck by a train.

In English the report is simply “that Tschanz had been found dead under his wrecked car….†The train has vanished, but at least Ms. Pol doesn’t make up Duerrenmatt’s mind for him on whether Tschanz’s death was an accident or suicide. Such are the joys of reading a book in two languages at once. If only my French were good enough to allow me to read Simenon in his own tongue!

You don’t need to be a linguist to catch some amazing blunders in the versions of Simenon that we get to see. In L’Affaire Saint-Fiacre, first published in French in 1931 and first translated by Margaret Ludwig as The Saint-Fiacre Affair in the double volume Maigret Keeps a Rendezvous (1941), a threat on the life of a countess brings Maigret back to the village where he was born and raised.

Very early in the morning he wakes up in the village inn and, purely for professional reasons, gets ready to attend Mass in the church where he’d been an altar boy. He goes downstairs and, in one of the later translations, the innkeeper asks him: “Are you going to communicate?†Even one who knows no French and nothing of Catholicism should be able to render the question in English better than that.

I don’t remember the title of the novel or who translated it but I vividly recall another Simenon where Maigret wakes up in yet another country inn and phones down for, as he puts it in English, “my little lunch.†Again, you don’t need to know more than a soupçon of French to figure out what the translation of petit déjeuner should be.

As this column is being cobbled together I’m in the middle of going over The John Dickson Carr Companion. And learning some odd trivia about Carr’s novels and stories that had never struck me before. How many of you remember that in the Carter Dickson novel She Died a Lady a gardener claims that on the previous night he went to see the movie Quo Vadis? The book was published in 1943 but, according to the Companion, its events take place in 1940.

Either way, Carr certainly couldn’t have been referring to the Quo Vadis? that we remember today if we remember the title at all, the 1951 Biblical spectacular that starred Robert Taylor and Deborah Kerr. There was a German silent version of the same story, released in 1924 and starring Emil Jannings, but what would a German silent be doing playing in England long after silents had been displaced by talkies and at a time when England and Germany were at war? More important question: What was Carr thinking?

The adaptations of Carr’s work dating back to the golden age of live TV drama back in the Fifties are not covered in the Companion, at least not in any detail. I happen to have some information on that subject, and chance has now given me an excuse to share it. Anyone remember Danger?

It was a 30-minute anthology of live teledramas, broadcast on CBS for five seasons (1950-55). My parents hadn’t yet bought their first set when the series began, and when it went off the air I was a child of 12 who hadn’t yet even discovered Sherlock Holmes and Charlie Chan at my local library.

I don’t think I ever watched the program, certainly not with any regularity, but I vaguely remember that one of its shticks was a background score of solo guitar music played by a guy named Tony Mottola (1918-2004). Obviously the producers of the show were hoping to duplicate the success of the CBS radio and TV classic Suspense, and the two Carr tales that were broadcast on Danger happened to be radio plays that he had written for Suspense back in the Forties. “Charles Markham, Antique Dealer†(January 2, 1951), was based on the radio play “Mr. Markham, Antique Dealer†(Suspense, May 1, 1943) and starred Jerome Thor, Marianne Stewart and Richard Fraser.

The director was Ted Post (1918-2013), who later moved into filmed TV series like Gunsmoke, Have Gun Will Travel and Rawhide and, thanks to impressing Clint Eastwood with his Rawhide work, got hired to direct big-budget Eastwood features like Hang ’em High (1968) and Magnum Force (1973).

We don’t know who directed “Will You Walk Into My Parlor?†(February 27, 1951) but it came from Carr’s radio drama of the same name (Suspense, February 23, 1943). The script was first published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, September 1945, and collected in Dr. Fell, Detective and Other Stories (1947) and, after Carr’s death, in The Dead Sleep Lightly (1983).

The cast was headed by Geraldine Brooks, Joseph Anthony and Laurence Hugo. Among the other top-rank mystery writers whose stories were adapted for Danger were Philip MacDonald, Wilbur Daniel Steele, A.H.Z. Carr, Anthony Boucher, MacKinlay Kantor, Steve Fisher, Q. Patrick, James M. Cain, Raymond Chandler and Roald Dahl.

The roster of authors who scripted original teleplays for the series included Paddy Chayefsky, Reginald Rose and Rod Serling, and among the directors who rose from this and other live teledramas to Hollywood household-name status were John Frankenheimer and Sidney Lumet.

The final episode of Danger was a live version of Daphne DuMaurier’s 1952 short story “The Birds,†which Alfred Hitchcock later adapted into one of his best-known films. I can’t imagine anything like Hitchcock’s bird effects being possible on live TV, but either I was watching something else on the night of May 31, 1955 or I went to bed early. If anything from this series is available on DVD, I haven’t heard of it.

Considering the dozens of scripts Carr wrote for Suspense as a radio series, one might have expected a pile of his radio scripts and short stories to have been used when the program became a staple item on prime-time TV.

In fact only one of his radio dramas and one of his short tales were adapted for the small screen. Among the earliest of the TV show’s episodes was “Cabin B-13″ (March 16, 1949), which starred Charles Korvin and Eleanor Lynn and was based on perhaps the best known and most successful Carr radio drama, first heard on Suspense on May 25, 1943 and collected in The Door to Doom and Other Detections (1980).

The second and final Carr contribution to Suspense was “The Adventure of the Black Baronet†(May 26, 1953), an adaptation of the Sherlock Holmes story written by Carr in collaboration with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s son Adrian (who according to Douglas G. Greene’s Carr biography did most of the writing) and first published in Collier’s for May 23, 1953, just a few days before the televersion.

As might have been expected, Basil Rathbone reprised his movie and radio role as Holmes. It might also have been expected that Nigel Bruce would have played Dr. Watson as he had so many times in the movies and on radio. I don’t know why he didn’t, but since he died only a few months later (October 8, 1953), the reason might have had to do with his health. In any event the Watson of this Suspense episode was played by Martyn Green of Gilbert & Sullivan fame.

As far as I’ve been able to find, Carr’s contributions to 30-minute live TV drama are limited to these four episodes. If any of his short stories or radio plays became the bases of filmed 30-minute dramas, I haven’t found them. There are two fairly well-known teledramas at greater than 30-minute length that owe their origins to Carr, but this column is long enough already so I’ll save them for next time.

Tue 11 Nov 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

MALAYA. MGM, 1949. Spencer Tracy, James Stewart, Valentina Cortesa, Sydney Greenstreet, John Hodiak, Lionel Barrymore, Gilbert Roland, Roland Winters. Director: Richard Thorpe.

Sometimes even a great cast can’t save a film bogged down with a lackluster storyline and undistinguished direction. That’s definitely the case with Malaya, an overall disappointing war movie about American smugglers working to get rubber out of Malaysia and into the hands of the Allied war effort.

If you think I’m being too harsh, consider the all-star cast that’s bogged down by a mediocre script: Spencer Tracy, James Stewart, Sydney Greenstreet, and Lionel Barrymore. Plus there are some great character actors in this one. John Hodiak as a federal agent, DeForest Kelley as a U.S. Navy officer, Gilbert Roland as a smuggler, and Roland Winters as a German plantation owner living in Malaysia.

And truth be told, Greenstreet really does steal the show in this one, making it worth watching for admirers of his work. In his final screen role, he portrays a character named The Dutchman, a scheming, world-weary saloon owner in Imperial Japanese-occupied Malaysia. There’s something both sad and charming about his character, a tired, obese man at war with his pet bird and, it would seem, with a life that has seemingly lost its purpose.

But it’s not enough to make Malaya anything other than a run-of-the-mill late 1940s wartime film, one that just feels like a tired effort designed to be both patriotic and informative about a lesser-known chapter in the Second World War.

James Stewart, of course, would soon get a new lease on celluloid life as a Western actor in Broken Arrow and in his collaborative efforts with Anthony Mann. Maybe that’s but one reason why this 1949 war melodrama isn’t very well known. But then again, there’s just no outstanding reason why it should be.

Mon 25 Nov 2013

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

THE POPPY IS ALSO A FLOWER (aka The Opium Connection). Made-for-TV movie, ABC, 22 April 1966. Expanded theatrical release, 1967 [?]. Yul Brynner, Stephen Boyd, Angie Dickinson, Rita Hayworth, Trevor Howard, E.G. Marshall, Omar Sharif, Eli Wallach, Jack Hawkins, Gilbert Roland, Hugh Griffith, Marcello Mastroianni, Trini Lopez, Senta Berger, Barry Sullivan, Nadja Tiller, Harold Sakata, Anthony Quayle, George Geret, Howard Vernon. Narrator: Grace Kelly. Screenplay by Jo Eisinger, based on a story by Ian Fleming. Directed by Terence Young.

“The poppy has no smell, not even the smell of evil. It’s just a ordinary flower, bright, innocent looking; and yet there are many many people who would have to be convinced — and it would take some convincing — that the poppy is also a flower.”

Grace Kelly: Prologue to

The Poppy is Also a Flower.

The amount of tripe written about this big budget made for television film done for the United Nations as an anti-drug project, and originally shown on ABC television in this country is amazing. For some reason it seems to drive some critics and viewers to extremes of near insanity far beyond any problems it has.

In reality it is a fair action adventure film with a point that deals with the efforts of the UN and the then Iranian secret police to deal with the trade in illegal opium.

I say any film that features Gilbert Roland as the villain, Rita Hayworth as a junkie, and E. G. Marshall in hand to hand combat with Harold (Oddjob) Sakata can’t be all bad. That’s not to mention wry Hugh Griffith as a opium selling bandit chief, Eli Wallach as a former Mafioso deported from the US, and Angie Dickinson as a mysterious woman getting ready for a shower with E. G. Marshall hiding under her bed is at least worth watching.

Did I mention the two girls in bikinis wrestling in the nightclub?

In 1966 that wasn’t something you saw often on television.

Trini Lopez even sings “La Bamba” and “Lemon Tree.”

Okay, that may not be entirely in its favor.

When UN agent Benson (Stephen Boyd) buys up the opium crop before drug king Serge Marko’s (Gilbert Roland) people can he promptly gets killed but not before destroying the opium. Now Marko is under pressure to secure the next supply or be out $10 million dollars.

Marko’s Manager: Serge Marko is a great guy to work for if you give him what he wants from you. If you can’t you’re dead.

Arriving in Iran to assist in the hunt for the opium connection is UN agent Sam Lincoln (Trevor Howard) and US Treasury Agent Coley Johns (E.G Marshall) No sooner have UN operative Omar Sharif and Iranian soldier Yul Brynner briefed them on their plan to irradiate the opium* so it can be tracked than Angie Dickinson shows up as Benson’s widow. But Benson wasn’t married.

Marshall and Howard make a good team with a nice playful attitude and give and take:

Lincoln: When duty calls …

Johns: You’re never there.

Considering everyone was working for nothing the performances are better than they had to be.

It’s not Oscar material, but it is nothing like the nonsense written about it.

The dubbing isn’t too good, but that’s hardly reason to have a hissy fit.

Leonard Maltin rates it a BOMB.

Leonard Maltin gives three stars to Roger Corman’s The Undead.

I’m just saying …

Sam distracts Angie while Coley searches her room which is how he ends up under her bed while she prepares to take a shower.

Mrs. Benson eludes them but they move on to Yul Brynner’s plan to raid the opium supply held by bandit chief Hugh Griffith and irradiate it, leading to a colorful raid on horseback in the mountains. It’s well staged and exciting shot on location among some spectacular scenery.

Hugh Griffith: The prophet has said only what is true must be believed, and fifty guns are fifty indisputable truths.

With the opium irradiated its now up to Lincoln and Johns to follow its trail back to the man behind the distribution, and the trail leads to Naples and deported gangster Happy Lucarno (Eli Wallach) who agrees to help to clear himself of suspicion.

Senta Berger has a nice bit as a drug addicted nightclub performer, and Rita Hayworth one of her last roles as the addicted wife of Marko the drug kingpin. Anthony Quayle is a South African ship’s captain who is a key part of Marko’s smuggling operation.

The plot builds to an exciting showdown with Johns and Mrs. Benson trapped by Marko on the Blue Train out of Marseilles to Lyon as they get the evidence from Mrs. Marko that will destroy him. There is a well staged battle between Marshall and Sakata in the baggage car and an exciting chase through the train yard with a final bitter triumphant line for Johns.

Johns: There’ll always be another one to take his place. The answer is miles and miles away — in the poppy fields.

The Poppy Is Also a Flower moves quickly, generates some suspense, features good location work, and unfolds logically to an exciting finale, pausing long enough to develop the characters of the two protagonists and well done vignettes by Brynner, Griffith, Quayle, Mastroianni. Berger, Wallach, and Hayworth. Considering it could have been preachy, stiff, and self important it is not only better than we might expect, but an exciting international chase.

You’ve seen better, but you’ve certainly seen much worse.

I’ve said it before. No film was ever worse for the presence of Gilbert Roland.

But I would like to know what it is about this film that gives some people such an irrational dose of dyspepsia. It’s not dull, it’s not stupid, and it’s not badly written or directed. But it rubs some people the wrong way to a surprising degree.

I can understand not liking it, but the reaction it provokes is all out of proportion to any of its failings.

Maybe that irradiated opium is more dangerous than I realized.

Or maybe the idea of E G. Marshall as James Bond causes some people to froth at the mouth.

* Perhaps the single silliest critique of this one are the countless reviews I’ve read worrying about what would have happened to the poor addicts if they got hold of the irradiated opium. Aside from being so ignorant as to not understand the nature of radiation or that opium is not sold in bulk , but cut and sold as cocaine, heroin, or morphine in doses so small as to make radiation poisoning impossible, the critics seem totally incapable of recognizing this is fiction.

If a drug addict got hold of a kilo of uncut opium chances are he would have died of something else long before radiation poisoning.

When did people get so politically correct they worry about non existent irradiated opium poisoning non existent drug addicts?

No fictional drug addicts were harmed in the making of this picture.

Wed 10 Aug 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 5.2: Theatre of Crime (UK)

British television in the 1950s and 1960s seemed to be choking itself on claustrophobic, heavily-theatrical studio-based plays (often live, sometimes taped). The BBC seemed shackled to the home theatre approach while newcomer ITV (from late 1955) tended to favor young TV writers (the provocative Armchair Theatre, ITV, 1956-74, for example) alongside somewhat wild and adventurous themes (the early Honor Blackman period of The Avengers, ITV, 1961-69).

Themes or strands, usually explained by the title, such as The Villains (ITV, 1964-65), Blackmail (ITV, 1965-66) and Seven Deadly Sins (ITV, 1966) or by a general heading like Suspense (both ITV, 1960; and BBC, 1962-63) were very much in style during the 1960s, but I have disregarded many of these because they represent nothing more than simple crime-and-comeuppance yarns. It is sad to consider that over a decade later such predictable collections as the 1978 ITV series Scorpion Tales didn’t improve the British TV genre very much.

The mid-1960s even saw a brief fascination with the fogbound period of Gaslight Theatre (BBC, 1965) and Mystery and Imagination (ITV, 1966; 1968; 1970). At the same time reveling in the Victorian-era police procedurals of Sergeant Cork (ITV, 1963-64; 1966-68) or penetrating the pea-soupers of Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965).

Here I have focused on the more obvious or more interesting genre anthologies shown on UK television during the past half century. (Some of them may even be found on DVD via Amazon-UK or NetworkDVD.)

One of the earliest was Tales from Soho (BBC, 1956), Berkeley Mather’s less-than-serious take on the notorious central London area. A curious point of interest to emerge from this lightweight collection, however, was one Chief Detective Inspector Charlesworth (played by John Welsh) who went on to his own series. Now featuring Wensley Pithey as Scotland Yard Detective Superintendent Charlesworth, the series was called Big Guns (BBC, 1958). Mather followed up with Charlesworth at Large (BBC, 1958) and Charlesworth (BBC, 1959).

Something of an unexpected pleasure, Hour of Mystery (ITV, 1957) was hosted by the fearsome Donald Wolfit. Among the episodes were “The Man in Half Moon Street” (with Anton Diffring), “The Woman in White”, Emlyn Williams’ “Night Must Fall” and “A Murder Has Been Arranged”, and Ivan Goff & Ben Roberts’s “Portrait in Black” (filmed in 1960 by Universal).

Armchair Mystery Theatre (ITV, 1960; 1964-65) was the summertime replacement for the long-running Armchair Theatre and featured stories by Michael Gilbert (“The Blackmailing of Mr. S.”, 1964), Julian Symons (“The Finishing Touch”, 1965) and Mary Belloc Lowndes (“The Lodger” (1965).

British-made (at MGM British Studios) for producer Herbert Brodkin’s Plautus Productions (US), the filmed anthology Espionage (NBC/US and ITV/UK, 1963-64) was one of the more intelligent contributions to the then-raging 1960s spy cycle. The Larry Cohen-scripted “Medal for a Turned Coat” (starring Fritz Weaver) remains a particular favorite with this writer.

BBC’s mid-1960s anthology Detective (BBC, 1964; 1968-69) has in the eyes of fans achieved almost legendary status, perhaps due in great part to this 45-episode series being “missing believed wiped.” For now, I’ll list just a few episodes that gave rise to some fascinating series:

The episode “The Drawing” (1964), scripted by Gil North [Geoffrey Horne], featured North-country Detective Sergeant Cluff (played by Leslie Sands) and soon became the rather leisurely but enjoyable Cluff (BBC, 1964-65). The episode “The Speckled Band” (1964), needless to say, went on to become Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1965) with Douglas Wilmer as Holmes and Nigel Stock as Watson; Peter Cushing took over as Holmes for a 1968 revival of the series. A third episode to spin-off from the anthology was “The Case of Oscar Brodski” (1964), from the works by R. Austin Freeman, and became the series Thorndyke (BBC, 1964) with Peter Copley as the methodical Doctor Thorndyke; this series, too, appears to be “missing believed wiped.”

Even while the legendary anthology Detective was enchanting grateful viewers, BBC’s Story Parade (1964-65) was lurking in the background with Ira Levin’s “A Kiss Before Dying” (1964) and, more importantly, Isaac Asimov’s “The Caves of Steel” (1964). This latter story featured the fascinating detective partnership of Elijah Baley (Peter Cushing) and the robot R. Daneel Olivaw (John Carson); depressingly, the original episode is said to no longer exist.

Outside of the 1960-63 Maigret series, BBC’s other celebration of Georges Simenon was captured in the non-Maigret collection Thirteen Against Fate (BBC, 1966). The collection was a stately-paced human condition drama, focusing on an individual in an unusual predicament; mercifully, the majority of these episodes have recently been rediscovered.

Leaning more on the horror and supernatural element, ITV’s very atmospheric Mystery and Imagination during the mid-1960s also found time to feature, among other dark mystery tales, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1966), Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Body Snatcher” (1966) and “The Suicide Club” (1970), and Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Uncle Silas” (1968).

Non-Sherlock Holmes stories made up Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (aka The Short Stories of Conan Doyle; BBC, 1967), a 13-part collection of stories ranging from the horror-fantasy of “Lot 249” to “The Mystery of Cader Ifan”. For the most part, the stories were dramatized by TV writer John Hawkesworth, who went on to immortalize Jeremy Brett’s Sherlock Holmes in the 1980s.

The series called Armchair Thriller (ITV, 1967) lasted a relatively short time but in its slight existence did manage to present Jack Trevor Story’s “In the Name of the Law” among its mere five outings. However, a more notable series under the same title (ITV, 1978; 1980) presented the six-part “A Dog’s Ransom” (1978) from the book by Patricia Highsmith, and the six-part “Quiet as a Nun” (1978) based on a book by Antonia Fraser (the first of a series of books that was spun-off as the 1983 series Jemima Shore Investigates for ITV). A six-part serial of Lionel Davidson’s “The Chelsea Murders” was also produced but not shown on UK TV until an edited version (condensed to 104 minutes) was broadcast in 1981. The Davidson novel was published in the U.S. in 1978 as Murder Games.

Starting off as a small series of plays under the ITV Playhouse: Rogues’ Gallery banner in 1968, including the wonderfully bawdy “The Lives and Crimes of Jonathan Wild and Jack Sheppard,” a six-part series called simply Rogues’ Gallery evolved in 1969 (ITV), featuring doom-laden tales of highwaymen and Newgate Prison.

Being recorded on icy-cold videotape didn’t somehow diminish the fascination of The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (ITV, 1971; 1973). Among the compelling dramas were William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki in “The Horse of the Invisible” (1971), Baroness Orczy’s Lady Molly of Scotland Yard in “The Woman in the Big Hat” (1971) and Jacques Futrelle’s Van Dusen in “Cell 13” (1973). This series represented one of the most interesting and enjoyable collections to appear on UK television.

Alternating between the woman-in-jeopardy story and the supernatural-fantasy, Brian Clemens’ Thriller (ITV, 1973-76) was a passable series of 65- and 75-minute mini-movies (albeit videotaped). Moments of enjoyment could be had in edge-of-the-seat dramas such as the would-be pilots “K is for Killing” (US: “Color Him Dead”; 1974), with Gayle Hunnicutt and Stephen Rea as a couple of amateur sleuths, and “An Echo of Theresa” (US: “Anatomy of Terror”; 1973) and “The Next Scream You Hear” (US: “Not Guilty”; 1974), the latter two with Dinsdale Landen as the likeable but overly confident private investigator Matthew Earp.

Anglia Television in association with 20th Century Fox Television produced Orson Welles’ Great Mysteries (ITV, 1974-75), with the slouch-hat-and-caped one hosting some intriguing presentations of Conan Doyle’s “The Leather Funnel” (1974), Wilkie Collins’s “A Terribly Strange Bed” (1974), and Dorothy L. Sayers’ “The Inspiration of Mr. Budd” (1975). The series was curiously reminiscent of Hammer Films’ teaming with 20th Century Fox in 1968 for the collection Journey to the Unknown which, in the latter instance, was resolutely geared to scare the living daylights out of the viewer.

The 13-part thriller anthology with stories connected by the theme of the telephone, Dial M for Murder (BBC/Warner Bros, 1974), was invested with more imagination (by producer Jordan Lawrence) than most contemporary thriller series. While some presentations were indeed tedious, most of the stories were simply dripping with suspense. One of them, Julian Symons’s “Whatever’s Peter Playing At?,” attracted the attention as being just a notch above the average.

Somehow you knew that when Tales of the Unexpected (ITV, 1979-86; 1988) was shown as Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected during its early years it was inevitable that “Man from the South,” “Mrs. Bixby and the Colonel’s Coat” and “Lamb to the Slaughter” would be included.

Thankfully, the series also drew on stories by Stanley Ellin, Bill Pronzini, John Collier, Henry Slesar, Ruth Rendell, Helen Nielsen, Peter Lovesey and Patricia McGerr among many others. Even so, the general feeling was that it had all been done much better before in Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Some of the stories in The Agatha Christie Hour (ITV, 1982) were just plain silly and embarrassingly dated but most, when taken on their own level, were unexpectedly rewarding. The stories featuring the delightful Maurice Denham as Parker Pyne who runs a sort of dream-fulfilment agency are among some of the best. One of these Pyne stories was “The Case of the Discontented Soldier,” about William Gaunt’s retired-but-restless military major who is given his own Bulldog Drummond adventure; Lally Bowers also appeared in this story as Mrs. Ariadne Oliver.

Based on the works by the title author, The Ruth Rendell Mysteries (ITV, 1987-2000) consisted of some of the author’s crime thriller tales as well as her Detective Inspector Wexford stories (the latter series starring George Baker). Among the non-Wexford episodes the series presented the three-part “Vanity Dies Hard” (1995), in which a lonely woman investigates the disappearance of her friend, the two-part “The Secret House of Death” (1996), where a woman becomes involved in the sudden death of the neighboring couple, and “Thornapple” (1997), featuring a young boy embroiled in poisonings and inheritance.

Rating as something of a disappointment was the nevertheless interesting-sounding Frederick Forsythe Presents (ITV, 1989-90), a short-run espionage drama based on stories by the title author. While all the components seemed in order with some fine directors (Tom Clegg, Lawrence Gordon Clark, Ian Sharp) and top-notch players (Beau Bridges, Brian Dennehy, Lauren Bacall, Tony Lo Bianco) the anthology suffered from the “too many chefs” syndrome of having too many producers and co-production companies.

A similar fate befell another interesting collection, Mistress of Suspense (ITV, 1990; 1992), based on six (hour-long) stories by Patricia Highsmith. Something to enjoy and savor became instead a jumbled concoction due to its myriad producers and co-production companies.

Murder in Mind (BBC, 2001-2003) was a diverting anthology of psychological crime dramas written by the brilliant Anthony Horowitz. The series turned out to be one of the true delights of genre TV. Horowitz composed such spellbinding stories as “Motive,” where a married couple believe they have committed the perfect murder; “Flashback,” in which a barrister “defends” the man he has framed for murder; and “Echoes,” where a woman investigates the past when a centuries-old body is found in her garden. Told from the detailed perspective of the hunted (the criminal) rather than the hunter (police), Murder in Mind may very well have been one of the high points of British television crime drama.

Although I’m sure there are many interesting anthologies that I’ve overlooked or have simply forgotten, the previous Parts and the above should be regarded simply as a general overview.

The next Crime & Mystery Part intends to survey The Black Mask Style, the late 1950s private eye phase of 77 Sunset Strip, Richard Diamond, Mike Hammer and Peter Gunn.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

Part 5.0: Theatre of Crime (US).

Part 5.1: Theatre of Crime (Hours of Suspense Revisited).

Sun 3 Jul 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

While most UK TV viewers surrendered to the spell of the Scotland Yard detective series during the 1950s, another sub-division of the TV genre was attracting something of a mini-following in Britain. The thriller serial.

Once settled into the post-war comfort of its role in British life, BBC Television began to develop the format of drama series and serials in earnest. A television serial template was struck, conforming at first to the nervous frenzy of “live” TV production and then to a uniform house style (the half-hour, six-part format).

When Francis Durbridge emerged in television in 1952 with the six-part thriller serial The Broken Horseshoe, the first of this type of programming, he combined the psychological thriller with the multi-part mystery.

The two notable genre-related forms had first appeared in the autumn of 1951: the single play Night of the Fourth (a detective story with a psychological theme; adapted from the German play Sprechstunde) and C.A. Lejeune’s six-part series of adaptations of Sherlock Holmes stories (presented as a series of self-contained, 35-minute plays). It is interesting that these two elements should form the basic structure of what became in the 1950s (and continued through into the 1960s): the BBC Durbridge mystery-thriller serial.

Durbridge was a radio writer (he had introduced BBC listeners to his amateur sleuth Paul Temple in 1938 [Send for Paul Temple]) whose name on the television credits could be relied upon to raise high hopes.

He treated his themes — murder, smuggling, treachery — with an unsentimental, civilised levity. There was in the writing a blend of the ironic and the ruthless, a switch in mood from amusing bafflement to disturbing seriousness, that was tartly refreshing in itself while requiring the utmost concentration and evenness of style in the direction.

While some type of criminal activity was usually embedded into the narrative (be it race fixing, dope smuggling, kidnap), it was the psychological bewilderment of the hero that was often the focus. The Teckman Biography (1953-54) and Portrait of Alison (1955) both move around characters who are supposedly dead but who mysteriously reappear, alive and informed and involved in a criminal enterprise.

In Melissa (BBC, 1964; remade 1974) it is the “wrong” person who is reported dead. A sense of timeliness was displayed in his Operation Diplomat in late 1952, concerning the mysterious disappearance of a top secret diplomat, and seemed to be perfectly keyed to the 1951 defection to Russia by British intelligence officers Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean (although Durbridge claimed coincidence).

The BBC’s treatment, with its rococo embellishments and general atmosphere of menace thickened by producer-director Martyn C. Webster’s staging in the early days (by producer-director Alan Bromly in later years), was as assured as any TV viewer at that time had a right to expect.

On the other hand some of the subsidiary scenes and characters were, if anything, under-developed. But the serials’ main weakness was the absence of expressive cutting and visual flow. As a result, certain half-way stretches of dialogue became tedious to watch; and the essential awareness of the writer’s shifting tensions yielded disappointingly to the easier mannerisms of any conventional thriller.

The typical Durbridge world of the thriller is comfortably middle class (of the post-war era), breezing with terribly English country-inn-and-gin types, often with the hero a self-sufficient artist or a writer, and always with the inevitable, and dependable, Scotland Yard man on hand when necessary.

Heavily dependant on dialogue and an end-of-episode hook, the serials were often little more than televised radio scripts, but this was to the serials’ advantage in the early days. In the Durbridge universe, everyone is tainted with a suggestion of menace or deceit. Absolutely no one is to be taken on face value. Information is deliberately withheld from the viewer, as well as the hero, almost to a point of irritation.

These complicated, intellectual crime riddles tended to overshadow his clearly stock characters (always in search of that elusive depth), somehow making him the ingenious master of the television mystery serial for almost two decades, until the times changed and the old-fashioned formula evaporated.

It wasn’t long before the UK TV schedules were thick with mystery-thriller serials, all designed and delivered in the Durbridge mould. Author Michael Gilbert studied the Durbridge form and wrote the underworld thriller The Crime of the Century (BBC, 1956-57); screenwriter Jimmy Sangster turned in the murder mystery Motive for Murder (ITV, 1957), and The Assassin (ITV, 1958), involving the hunt for a killer-for-hire; and Anthony Berkeley’s 1937 novel Trial and Error, about a murderer setting out to prove the innocence of a wrongly accused man, was adapted as the six-part Leave It To Todhunter (BBC, 1958).

Rival channel ITV’s serial master was Lewis Greifer, a prolific radio and TV writer whose work in the serial format (in collaboration with producer-director Quentin Lawrence) was not too far removed from the Durbridge world of psychological terrors. The hero faces an identity crisis in the murder mysteries Five Names for Johnny and Web, both 1957; and in The Man Who Finally Died (1959) is confronted with the return of a “dead” man, leading to a convoluted Durbridge-style unravelling of the past.

Astute enough to notice the secret agent genre forming on television by the beginning of the 1960s (with the growing popularity of ITV’s Danger Man; the 1960-62 half-hour series), Durbridge created the lengthy serial The World of Tim Frazer (BBC, 1960-61) featuring a working-class engineer who is recruited by a shadowy government department into acting as an undercover agent.

The unprecedented 18-part serial was surprisingly well-received and even heralded as the successor to the still-popular (via radio) Paul Temple. The detached and skeptical Frazer (performed by a brooding Jack Hedley with insolent confidence) was essentially an outside observer of events who had licence to move through the well-heeled Durbridge milieu with barely-concealed contempt of what was by now stock 1950s British types.

The peculiar success of Tim Frazer continued Durbridge’s celebrity as the master craftsman of the British thriller serial (other contemporary thriller serials were gauged on their ability to render the “Durbridge touch”; Lynda La Plante would receive similar genre worship during the 1980s).

Whether he was blinded by the celebrity or simply coerced by BBC producers hungry for more of the same, Durbridge pressed ahead into the following decades (up until his last serial, Breakaway, in 1980) by giving the viewer (and the producer) more of what he thought they wanted: long, drawn-out, unnecessarily complicated plots populated by thinly developed 1950s-type characters, leading up as always to a sudden surprise revelation in the final episode.

In a television-viewing age that had already experienced by this time a post-Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78) world of stark social realism (explicit violence, police corruption, race conflict, etc.), Durbridge proceeded, seemingly quite oblivious of events around him, to turn out facsimiles of his 1950s plots.

What was at one time the electrifying anticipation of the coming of “another Durbridge thriller” in the 1950s and 1960s had developed by the 1970s into a non-event of bafflement and disappointment.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Thu 21 Apr 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

This section could be called the Golden Age Traditionalists. Early crime and mystery drama on television is, quite simply, divided into two strands. The British one (namely BBC), which had its roots in Radio and in the Theatre, and the American one (namely NBC), which had its roots in Radio and (in a limited capacity) in the Cinema.

British television (BBC), in the beginning, experienced something of a race in technology. Inventor John Logie Baird’s mechanical system versus EMI-Marconi’s electronic system. In February 1937, the EMI-Marconi system was formally adopted by BBC Television.

The BBC’s Royal Charter made it their duty to “inform, educate and entertain.” The first two were served with TV news broadcasts and with various instructional documentaries. The third element started off as little more than “photographed stage plays.”

It was the lofty, upper-middle-class BBC view of the time that either scenes from West End theatre productions or studio-produced adaptations of artistically intellectual novels made up almost the only “entertainment” programmes.

However, television Crime & Mystery genre history was made in 1937 — when George More O’Ferrall produced the medium’s first (hitherto unperformed) Agatha Christie play, The Wasp’s Nest, on 28 June 1937. The 25-minute TV presentation, broadcast live, starred the portly Francis L. Sullivan, a popular actor of the time who had earlier achieved a great success as Hercule Poirot in Christie’s 1931 West End stage hit Black Coffee.

The other great television genre “first” was the NBC experimental broadcast of Conan Doyle’s 1924 “The Adventure of the Three Garridebs,” transmitted from the stage of the Radio City Music Hall on 27 November 1937 as The Three Garridebs. Luis Hector played Sherlock Holmes and William Podmore was Dr. Watson.

Arriving in the latter part of the literary genre’s Golden Age, BBC presentations included television adaptations of plays by Emlyn Williams (Night Must Fall, 1937), Edgar Wallace (The Case of the Frightened Lady, On the Spot, Smoky Cell and The Ringer, all 1938), Christie (Love from a Stranger, 1938), Patrick Hamilton (Gaslight, 1939) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Tell-Tale Heart, 1939).

Of related interest was a black comedy about 19th century body snatchers Burke and Hare, and their mentor Dr. Knox, in The Anatomist (1939; presented again in 1949). The first actual UK made-for-television genre series was Telecrime (1938-39), a programme consisting of 10 and 20-minute whodunits set to test the viewer on their powers of observation and deductive reasoning.

The BBC hurriedly closed down their Television Service in September 1939 due to the outbreak of war in Europe.

Telecrimes (now plural) returned in post-World War Two 1946, written again by Miles Horton and now with James Raglan as Inspector Cameron. A similar viewer-participation series, Consider Your Verdict, was shown in 1947.

Starting in July 1946, the works of Edgar Wallace continued to be popular with The Ringer, The Green Pack (1947), On the Spot and The Case of the Frightened Lady (both 1948), and The Squeaker (1949) adapted for television.

Joining the Wallace adaptations, among others in the TV Crime & Mystery genre, were G.K. Chesterton’s play Magic (1946), the Anthony Armstrong thrillers Ten-Minute Alibi (1946), and later, in 1948, The Case of Mr. Pelham. In Gilbert Thomas’ Scotland Yard detective play Murder Rap (1946), Desmond Llewelyn played the intrepid Inspector Fearon.

Patrick Hamilton also saw plenty of small-screen time, with Rope (January 1947), featuring young Dirk Bogarde as murderer Charles Granillo, Gaslight (1947 and 1948), The Duke in Darkness (1948) and The Governess (1949).

Fans greeted Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1947) and Martin Vale’s The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947) with glee. Agatha Christie was represented with Love From a Stranger (1947), adapted by Frank Vosper, and Three Blind Mice (1947), the latter written especially by her for BBC Television to mark Queen Mary’s birthday.

There was also a version of Maria Marten, or The Murder in the Red Barn (1947), with William Fox in the villainous Tod Slaughter role. Dorothy L. Sayers (and Miss St. Clare Byrne) had Busman’s Honeymoon (October 1947) adapted for television, with Harold Warrender as Lord Peter Wimsey and Ruth Lodge as Harriet. Toward the end of 1947, a dramatization of George du Maurier’s Trilby (October) was shown, with Abraham Sofaer as the spooky Svengali.

J. B. Priestley’s intriguing drama An Inspector Calls was dramatized in May 1948, with George Hayes as Inspector Goole (the Alastair Sim role in the famous 1954 film version). From May 1948, saturnine storyteller Algernon Blackwood told a chilling Saturday Night Story straight to camera. Anthony Holles was Inspector Hanaud in A.E.W. Mason’s At the Villa Rose (1948). On Christmas Eve 1948, the BBC presented He That Should Come, a Nativity play written by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Under the TV programme banner of Triple Bill (June 1949), Sidney Budd adapted Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution (presented alongside Denis Johnston’s Irish Rebellion play The Call to Arms and Peter Brook’s one-man [Marius Goring] show Box for One). Christie’s body-count play, then called Ten Little Niggers, was produced in August 1949.

At the end of the year, as a part of BBC’s Edgar Allan Poe Centenary (in October 1949), the TV play versions of The Cask of Amontillado, Some Words With a Mummy and The Fall of the House of Usher (all adapted by Joan Maude and Michael Warre) were presented.

Towards the end of the decade, television began adopting regular programming schedules. Emulating the long-standing BBC Radio form, strands like Children’s Television, Sport, Theatre, and Variety began producing their own series and soon established their weekly slots.

Outside of radio (where other genre authors composed works especially for BBC Radio, such as Sax Rohmer with the eight-part serial Shadow of Sumuru, December 1945-January 1946), the TV genre consisted mainly of documentaries — for example, It’s Your Money They’re After (1948), with Scotland Yard explaining some of the then-new and ingenious frauds, and The Man On the Beat (1949), showing how a policeman becomes our protector.

There was also the occasional, early drama series: The Inch Man (1951-52), concerning the adventures of a hotel house detective, and the now-legendary Sherlock Holmes (October-December 1951) series of stories starring Alan Wheatley as Holmes and Raymond Francis as Watson; the stories were adapted for television by Observer film critic C.A. Lejeune. (But more on the TV Sherlock Holmes later.)

1952 saw the beginning of the Francis Durbridge suspense thrillers, bringing UK television’s early Crime & Mystery period to a close.

In the second section of this two-part Evolution of the TV Genre, I will be looking at the same 1930s/1940s period in US television.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Fri 19 Nov 2010

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

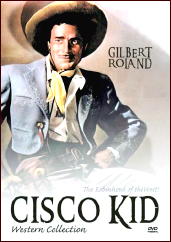

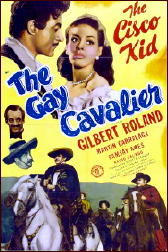

THE CISCO KID WESTERN COLLECTION:

â— THE GAY CAVALIER. Monogram Pictures, 1946. Gilbert Roland, Martin Garralaga, Nacho Galindo, Ramsay Ames, Helen Gerald, Tristram Coffin. Director: Willliam Nigh.

â— BEAUTY AND THE BANDIT. Monogram Pictures, 1946. Gilbert Roland, Martin Garralaga, Frank Yaconelli, Ramsay Ames, Vida Aldana. Director: William Nigh.

â— SOUTH OF MONTEREY. Monogram Pictures, 1946. Gilbert Roland, Martin Garralaga, Frank Yaconelli, Marjorie Riordan, Iris Flores. Director: William Nigh.

â— RIDING THE CALIFORNIA TRAIL. Monogram Pictures, 1947. Gilbert Roland, Martin Garralaga, Frank Yaconelli, Teala Loring, Inez Cooper. Director: William Nigh

â— ROBIN HOOD OF MONTEREY. Monogram Pictures, 1947. Gilbert Roland, Chris Pin Martin, Evelyn Brent, Jack La Rue, Pedro DeCordoba, Donna DeMario. Director: Christy Cabanne.

â— KING OF THE BANDITS. Monogram Pictures, 1947. Gilbert Roland, Angela Greene, Chris Pin Martin, Anthony Warde, Laura Treadwell, William Bakewell. Director: Christy Cabanne.

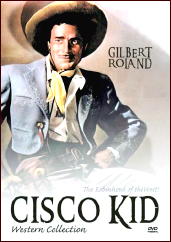

Speaking of Gilbert Roland and Widely Available (as I was at the end of my previous review ), his six Cisco Kid movies from Monogram are out on DVD in pristine prints not seen since their original release. This is not, however, a cause for general rejoicing, as the films themselves could be charitably described as lack-luster.

Gilbert Roland was a romantic leading man in the silent films, but despite his melodious voice and relaxed acting, he slipped badly in the 30s and 40s: he can be glimpsed in humiliatingly small parts in The Sea Hawk (1940) and My Life with Caroline (1941) and he landed in a Columbia serial, The Desert Hawk in ’44.

In 1949 John Huston resurrected his fortunes with a meaty part in We Were Strangers that led to a satisfying career as a busy character actor, but in 1946 he was doing pretty much anything that came along — and doing it surprisingly well.

Roland’s Cisco Kid movies have their moments, but they are mostly listless and formulaic. Action is scarce and rather routine (except for a couple of sword fights in The Gay Cavalier and Riding the California Trail) and as for formula, well, in Cavalier Martin Garralaga plays an impecunious rancher who wants to wipe out his debts by marrying his daughter to a shifty Americano. It is up to Cisco to rescue her.

In California Trail, Garralaga plays a rancher in debt to bad guys who wants to absolve his debt by marrying off his niece to a Yankee ne’er-do-well. And in South of Monterey, he’s a Police Captain who owes his job to American bad-guy Harry Woods and pressures his sister to marry him.

Okay, so there’s a lot of bland-and-predictable in these films, but they are saved, redeemed even, by Gilbert Roland’s swaggering, sexy portrayal of the Cisco Kid. Roland, the only Mexican actor to play Cisco, wrote some of his own dialogue for these films, which demonstrates how seriously he took the part.

His macho swagger and general air of devil-may-care recall Doug Fairbanks in The Gaucho (1927) and even in the reduced circumstances of these poverty-row westerns he looks relaxed, expansive, and damn sexy — which isn’t easy in a B-movie.

Errol Flynn and Clark Gable projected rugged male sexiness easily with the vast resources of Warner Brothers and MGM behind them, but Gilbert Roland somehow managed the same effect on the tiny budgets of a studio renowned in those days as Hollywood’s dumping ground. And somehow he keeps one watching these tawdry films long after their promise has waned.