Search Results for 'Christianna Brand'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 18 Jun 2023

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

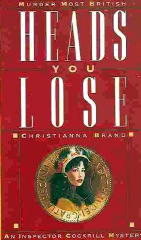

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Heads You Lose. Inspector Cockrill #1. John Lane/Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1941. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1942. Reprint editions include Bantam, paperback July 1988. July 1 13.SO>

As you might deduce from the title, murder by decapitation, three times over. Not exactly what you’d call a “cozy” mystery, although all the trappings are there: a small English village, the squire’s manor, only six suspects. Inspector Cockrill investigates.

Patterned after John Dickson Carr, although there’s no locked room — the body found in the snow with no footprint$ around has an easy explanation. But with events bordering the bizarre, and with every word and scene full of extra meaning, it’s Carr a11 right.

– Reprinted from Mystery.File.6, June 1980.

Thu 29 Oct 2020

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY RAY O’LEARY:

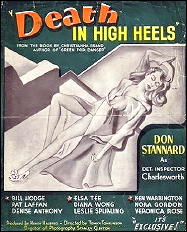

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Death in High Heels. Inspector Charlesworth #1. John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1941. Scribner, US, hardcover, 1942. Carroll & Graf, US, paperback, 1989. Film: Marylebone, UK, 1947 (with Don Stannard as Inspector Charlesworth).

A great title for foot fetishists, but it turns out that footwear has nothing to do with the story. This was Ms. Brand’s debut novel, and does not feature her series detective Inspector Cockrill.

Miss Doon, one of two chief assistants to a Mr. Bevan (and one of his many bedmates) who owns and operates an exclusive Dress Shop, dies from oxalic poisoning (Oxalic apparently being used to clean hats), and it turns out that most of her associates who had Opportunity for the crime also had Motive. Young Inspector Charlesworth, one of those innumerable upper-class policemen of the “Golden Age” of British Mysteries, is assigned to the case and immediately develops a crush on the chief suspect, a married saleswoman.

A good example of the Classie British Mystery Novel (though not a great one} with credible characters, some humor — including a chapter where Charlesworth becomes convinced that one of the suspects has killed his (the suspect’s) boyfriend and put his body in a trunk at the Lost and Found – and enough witty dialogue to get over the quiet parts.

— Reprinted from A Shropshire Sleuth #71, May 1995.

The Inspector Charlesworth series –

Death in High Heels (n.) Lane 1941

Death of Jezebel (n.) Bodley Head 1949 [with Inspector Cockrill]

London Particular (n.) Joseph 1952 [with Inspector Cockrill]

The Rose in Darkness (n.) Joseph 1979

Sat 27 May 2017

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

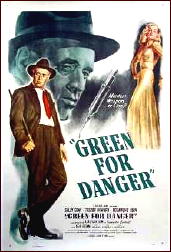

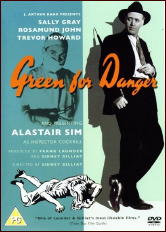

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Green for Danger. John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1945. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1944. US paperback reprints include: Bantam F2858, 1965; Perennial Library, 1981; Carroll & Graf, 1989. Film: General Film, UK, 1947 (with Alastair Sim as Inspector Cockrill).

Christianna Brand has written mainstream novels, short stories, and juveniles, but she is best known for her detective novels featuring Inspector Cockrill of the Kent, England, County Police. Cockrill (known affectionately as Cockle) is a somewhat eccentric, curmudgeonly fellow — less a character than a catalyst in the cases he solves. He delights in setting up situations that force the murderer’s hand, and the murderer’s identity usually seems quite obvious to the reader, until Brand introduces a twist designed to delight.

At the beginning of Green for Danger, an unlikely group of characters assemble at a military hospital during the blitz of World War II. Each has his reasons for escaping his previous environment; each has expectations of what this assignment will bring. What none of them suspects is that a patient — the postman who, incidentally, delivered their letters saying they were coming to Heron’s Park Hospital — will die mysteriously on the operating table, and that all of them will come under Inspector Cockrill’s scrutinizing eye as murder suspects.

The characters are numerous, but Brand nonetheless manages to instill unique qualities that enlist the reader’s sympathy and create dismay at the revelation of the murderer. The solution is plausible, the motivation well foreshadowed, and the evocation of both the terror and fortitude of those who endured the German bombing is very real indeed.

Inspector Cockrill has also solved such cases as Heads You Lose (1941), Death of Jezebel (1948), London Particular (1952), and The Three-Cornered Halo (1957).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 10 Aug 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marv Lachman

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Green for Danger. Lane, UK, hardcover, 1945. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1944. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including Carroll & Graf, US, 1990.

Christiana Brand’s Green for Danger has been reprinted more than most mysteries, such is its reputation. The latter has undoubtedly been enhanced by the popular 1947 British film version with Alistair Sim, Leo Gena, and Trevor Howard. Now, Carroll & Graf has reprinted it in trade paperback at $7.95, and if this attractive edition garners some new readers for the book, it will have served its purpose.

It is an ingeniously plotted tale of murder at a British hospital during an air raid, but it is equally a splendid picture of human beings who are exhausted and operating at the end of their endurance. This is a book which can speak very nicely for itself, but this version has two bonuses in the form of a fine preface by H. R F. Keating and an equally good introduction by Otto Penzler which put the book and its author’s career into perspective.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

Wed 23 Oct 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Death in High Heels. Charles Scribner’s Sons, US, hardcover, 1942, 1954; John Lane-Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1941. Carroll & Graf, US, paperback, 1989.

There are some problems among the personnel at Cristophe et Cie, home of possibly haute couture. Frank Bevan, proprietor and manager, has a tendency to become physically interested in his employees, with the exception of Macaroni, the secretary, and Mrs. ’Arris, the charlady, and possibly Mr. Cecil, the dress designer, the latter of whom might have enjoyed Bevan’s attentions. Some jealousy and backbiting also have arisen about a position at the new branch at Deauville.

It would seem unlikely that such hard feelings would give rise to anything worse than hairpulling. But one afternoon Miss Boon, Bevan’s left hand in the business and the chosen one to go to Deauvilie, becomes ill and dies as a result of the ingestion of oxalic acid.

To find out whether Boon’s death was accident, suicide or murder, Inspector Charlesworth, young, inexperienced, and given to falling in love at first sight and to thinking each of these loves is the real thing, is assigned to the case. No sooner does he discover that it was indeed murder than he is faced with deciding if Boon was in fact the intended recipient of the poison.

Charlesworth is baffled by the complexities of the case. His superior turns over primary control of the case to Charlesworth’s senior, Inspector Smithers, not knowing that between the two of them is hearty detestation. Smithers, of course, suspects and arrests one of the shop’s mannequins, the very female that Charlesworth has fallen in love with. Fortunately, Charlesworth comes to the rescue by discovering the guilty party.

Another excellent mystery novel by Brand. It is well clued, well written, amusing — all that her fans have come to expect of her.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

NOTE: This book has been reviewed once before on this blog, the earlier occasion by Curt Evans. Check out what he had to say here.

Fri 23 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Death in High Heels. John Lane/Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1941. Charles Scribner’s Sons, US, hc, 1942. Paperback reprints: Pan, UK, 1948; Carroll & Graf, US, 1989 (shown). Series character: Inspector Charlesworth. Film: Marylebone, 1947; with Don Stannard as Det. Charlesworth. Director: Don Stannard.

I found Christianna Brand’s ’prentice novel still quite enjoyable on my second reading. While the mystery plot is only mildly interesting, being not tremendously complex and but lightly clued, Brand does a fine job of keeping the reader hanging on to rapidly shifting suspicions and turns of events — a technique she beautifully perfected a few years later in her widely acknowledged masterpiece, Green for Danger. (One event here, though, rather melodramatically absurd, is hard to swallow.)

What I enjoy most about Death in High Heels is the setting, which is one of the best realized of the Golden Age period (if we stretch the usually accepted years of the Golden Age just slightly). The dress shop atmosphere, with its colorful coterie of ladies and men (along with designer Mr. Cecil, who is somewhere in between the two previously mentioned sexes), is strongly and amusingly conveyed.

The dumb stereotype of British Golden Age mystery — that all these books take place in upper-class country houses, posh London flats or highly stratified Cranford-style villages — certainly is belied by Brand’s first novel, which takes place in a hard-nosed London business establishment where most of the characters are working girls who by no means are economically well-settled.

Brand was such a “girl” and worked in such an establishment herself, I believe, which certainly lends authenticity to her setting in Death in High Heels.

Especially refreshing in Death in High Heels is the light badinage about sex. The ladies are breezily and pleasantly irreverent on this subject, while the presentation of Mr. Cecil and “the boyfriend” seems quite explicit for the time (even the most obtuse reader of the day must have recognized s/he was reading about a “gay” couple).

Unlike some of Ngaio Marsh’s portrayals of gay men from the same period, Brand’s presentation of the colorful Mr. Cecil, while admittedly comically broad, comes off, in my view, as genuinely amusing rather than merely demeaning. And each of the numerous dress shop ladies comes across as a distinct individual, a distinct achievement on the part of the author.

Though nearly seventy years old, Death in High Heels has dated not much at all. It’s one of the best “workplace atmosphere” mysteries of the period, I believe.

Editorial Comment: The crime fiction of Christianna Brand has been reviewed several times on this blog. Most recently was Marcia Muller’s review of Green for Danger, from 1001 Midnights. Following this link will lead you to that review, which in turn contains links to four earlier reviews.

Mon 17 May 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller:

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Green for Danger. Dodd, Mead, hardcover, 1944. UK edition: John Lane/The Bodley Head, hc, 1945. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback. Film: Individual Pictures, UK, 1946, with Alastair Sim as Inspector Cockrill.

Christianna Brand has written mainstream novels, short stories, and juveniles, but she is best known for her detective novels featuring Inspector Cockrill of the Kent, England, County Police.

Cockrill (known affectionately as Cockie) is a somewhat eccentric, curmudgeonly fellow — less a character than a catalyst in the cases he solves. He delights in setting up situations that force the murderer’s hand, and the murderer’s identity usually seems quite obvious to the reader, until Brand introduces a twist designed to delight.

At the beginning of Green for Danger, an unlikely group of characters assemble at a military hospital during the blitz of World War II. Each has his reasons for escaping his previous environment; each has expectations of what this assignment will bring.

What none of them suspects is that a patient — the postman who, incidentally, delivered their letters saying they were coming to Heron’s Park Hospital — will die mysteriously on the operating table, and that all of them will come under Inspector Cockrill’s scrutinizing eye as murder suspects.

The characters are numerous, but Brand nonetheless manages to instill unique qualities that enlist the reader’s sympathy and create dismay at the revelation of the murderer.

The solution is plausible, the motivation well foreshadowed, and the evocation of both the terror and fortitude of those who endured the German bombing is very real indeed.

Inspector Cockrill has also solved such cases as Heads You Lose (1941), Death of Jezebel (1948), London Particular (1952), and The Three-Cornered Halo (1957).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Previously reviewed on this blog:

Fog of Doubt (London Particular), by Steve Lewis

The Spotted Cat and Other Mysteries, by Mike Tooney

Heads You Lose, by Mike Tooney

Fog of Doubt (London Particular), by Kevin Killian

Sat 15 May 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Fog of Doubt. Carroll & Graf, paperback reprint, 1984. Hardcover edition: Charles Scribner’s Son, US, 1953. First published in the UK as London Particular, hc, 1952. Earlier US paperback: Dell #881, 1953.

On the night of a terrific London fog, a murder is committed, and only a handful people could have done it – excluding the ubiquitous tramp, of course. Inspector Cockrill’s problem is that all of them have alibis and/or no motive.

This is supposedly a classic of detection, in which it all comes down to the last line, but in my opinion? I’m not so sure.

Either it was a spontaneous crime, a chance opportunity quickly taken, or a devious scheme completely planned in advance. It can’t be both, and as far as I can see, the ending just doesn’t work. The events described are simply in the wrong order.

Worse, a conversation a police officer overhears on pages 93-94 reveals quite a bit of information they, the police, could have used, but it’s Never Mentioned Again. (In a bit of Confusion on my part, I thought the police must have been in on the killing…!?)

Cockrill has barely any presence in the story at all — I got the feeling the case would have ended exactly the same way, with or without him. The tradition of Christie-Carr-Queen is mentioned on the front cover, but if this is one of Brand’s best, it is easily seen why she’s mostly forgotten today.

PostScript: This is the kind of commentary you’re forced to resort to when you don’t want to give too much of the story away, but when the story is essentially the ending, what else can you do?

— Reprinted from Mystery*File #35, November 1993, somewhat revised.

[UPDATE] 05-15-10. What this kind of negative review on my part makes me want to do today is find my copy of the book and read it again, especially since the author is still well regarded today.

I seldom pan a book as severely as I did this one, so what I’d really like to know now if it’s really as bad as I thought it was then. Did I read it wrong? Was there something I missed? I don’t know, and I wish I did.

[UPDATE #2] 05-17-10. I’ve just posted Marcia Miller’s review of Green for Danger, one of Christianna Brand’s earlier mysteries (1945). I mention this because I quoted from her review in my Comment #2.

I’ve also belatedly discovered that Kevin Killian reviewed Fog of Doubt here on the blog about a year and a half ago. He goes much further into detail about the plot, finds some of the same problems with it, but overall he liked the book much more than I did. Follow the link, and you’ll see what I mean.

Tue 31 Mar 2009

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – The Spotted Cat and Other Mysteries from Inspector Cockrill’s Casebook. Crippen & Landru, hardcover & trade paperback, November 2002. Edited by Tony Medawar.

Christianna Brand’s Inspector Cockrill appeared in almost a score of novels, short stories, and even a play, most of which were published in her lifetime. Crippen & Landru have done us a service in preserving all of the short stories that saw publication — and more.

From the back cover blurb:

INSPECTOR COCKRILL INVESTIGATES

“Christianna Brand (the pseudonym of Mary Christianna Milne Lewis, 1907-1988) was a supreme mistress of the classic detective story, with twists and turns, and all the clues fairly given to the reader. The wizened, bird-like Inspector Cockrill of the Kent police starred in Green for Danger, one of the greatest detective novels to emerge from World War II, but The Spotted Cat is the first collection of all of the short stories about him. Five of the stories have never previously appeared in a Brand volume, and one of them is published here for the first time. The book also includes a genuine find, a previously unpublished three-act detective drama featuring Cockrill.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

CONTENTS:

Introduction (“In and Out of Darkness”) by Tony Medawar: A well researched article about Brand’s life and progress as a writer.

1. “Inspector Cockrill” (1978) by Christianna Brand: The author writes an amusing but affectionate biographical sketch of her most famous character, patterned closely after her father-in-law, a medical doctor.

“He [Cockie] is not one for the physical details of an investigation: ‘meanwhile his henchmen pursued their ceaseless activities’ writes his creator, not too sure herself exactly what those would be; and he is content to leave fingerprint powder and magnifying glass to the experts, using their findings in a process of elimination, to get down to the nitty-gritty from there on.

“He has acute powers of observation, certainly; a considerable understanding of human nature, a total integrity and commitment, much wisdom; and as we know a perhaps overlong experience of the criminal world …. Above all — he has patience.” True, “he will have compassion for the guilty”; nevertheless, “he can be forthright and stern …. There is no false sentiment about Chief Inspector Cockrill, none at all.”

2. “After the Event” (from Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, January 1958 as “Rabbit out of Hat”)

In a famous play by Shakespeare, Othello strangles his (reputedly) faithless wife; back in the 1920s, an actor playing Othello at the time apparently did the same thing in the lady’s dressing room backstage. An unnamed Great Detective reminisces about the case to a group of acquaintances, among them Inspector Cockrill, who predictably pokes holes in the speaker’s handling of the situation, much to the Great Man’s chagrin. And one should always remember, as Cockrill does, that theatrical people have been known to put on an act ….

Note: Inspector Cockrill, cracking walnuts and irritating the Great Man, is an armchair detective in this story.

3. “Blood Brothers” (from EQMM: September 1965)

Brotherly love, like all relationships, seems to have its limits. Two siblings, identical twins, have been with the same girl, competing for her affections; but now, it seems, she is pregnant by one of them. The situation is further complicated by several factors: The girl knows that one of the brothers has killed a small boy in a hit-and-run; she is also married to a huge brute doing time in one of HM’s prisons but due soon for release; and one of the siblings harbors enough hatred to let the other take the fall for first-degree murder.

Inspector Cockrill — who enters in the last third of the story — simply lets things take their natural and inevitable course, as David and Jonathan rapidly degenerate into Cain and Abel … with a twist.

Note: Instead of being told in the third person, this story is narrated by one of the brothers.

4. “The Hornet’s Nest” (from EQMM: May 1967 as “Twist for Twist”)

When wealthy Cyrus Caxton — a nasty piece of work, that one — does a Brodie face first into his half-eaten peach, no one of his acquaintance is moved to shed a tear, save his attractive wife. Inspector Cockrill is called in and confronts a fine set of likely suspects; in the end, the Inspector, Ellery Queen-like, has proposed two plausible solutions before pouncing on a third, actual one.

Elizabeth comments on Cockie’s method: “He’s — he’s sort of teasing us; needling us, trying to make us say something.” Presciently, the Inspector early in his investigation remarks: “There has been a plan here, doctor: no simple matter of a lick of poison scraped out of a fortuitous tin, smeared on to a fortuitous peach-in-liqueur; but a very elaborate, deep-laid, long-thought-out, absolutely sure-fire plan.”

5. “Poison in the Cup” (from EQMM: February 1969)

CASE HISTORY: Stella Harrison is a small-town doctor’s wife more than a little bored with her lot in life; her husband Richard, a painfully honest individual, seems oblivious to her incipient disaffection — and equally unaware of her secret love for his partner, Frederick Graham. A nurse at the hospital, Ann Kelly, however, makes no secret of her undying love for Stella’s husband… Ann makes a fatal mistake, though, when she decides to stage a bogus suicide attempt in Dr. Harrison’s surgery …. DIAGNOSIS: Murder. PROGNOSIS: Life in prison for a killer who remembers every detail but one ….

Note: The murderer’s identity is never in doubt; we see the crime committed. The interest lies in how Chief Inspector Cockrill, a la TV’s Columbo, will trip up the perp — because this killer uses the truth as a cover.

6. “The Telephone Call” (from EQMM: January 1973 as “The Last Short Story”)

The best-laid plans do often go off the tracks, don’t they? A young man short of money conceives an intricate plot to acquire a lot of it in a hurry; his girlfriend half-jokingly suggests it: “You’ll have to murder your rich Aunt Ellen”; and he improves it: “Yes, and let Cousin Peter swing for it; if he did, I’d scoop the lot.”

And so he carefully begins building two alibis, one for himself and a negative one for the hapless Peter… And it all works beautifully — except for one thing, and you don’t have to be Detective Inspector Cockrill to figure it out.

Note: The bulk of this story is told in the form of a written confession.

7. “The Kissing Cousin” (from Woman: June 2, 1973)

Cranky old Aunt Adela has millions, but true to form she is parsimonious and secretive about her wealth; her niece Franca doesn’t really care if she inherits — but there’s someone she knows who is greatly interested in the old lady’s money, someone willing to kill for it. When Aunt Adela is found dead, her house ransacked for a missing will, Chief Inspector Cockrill zeroes in on Franca: “You inherit,” he says. “And you hold the only key to the door.” But the killer already has Franca marked for murder, and knows as well the secret Keeper, the cowardly mastiff, is harboring ….

Note: It seems Cockie doesn’t really solve this one, and takes no active part in apprehending the murderer; he is a secondary character here.

8. “The Rocking-Chair” (from The Saint Magazine: August 1984)

Taking a break from a village fete “on a boiling hot afternoon” to have “a little booze-up”, the Duchess of St. Martha’s Island retires to her castle with Miss Maud Trumble, “rich and famous author of dozens of really quite terrible books”, and Chief Inspector Cockrill.

Seemingly gripped by a feeling of guilt, Miss Trumble, “mildly squiffy,” relates her involvement in the unresolved Case of the Three Dead Ladies: “three women lying dead, spread out like a trefoil clover-leaf, their poor heads forming the centre point…” Cockie and the Duchess both prove able armchair detectives by “solving” this fifteen-year-old case.

“It was like a detective story, thought the Duchess, where the clues are placed not so much squarely before the reader as slightly obliquely, so that they come out as not quite what in fact they are.” Just so.

9. “The Man on the Roof” (from EQMM: October 1984)

English village life is normally uneventful, but not today: The much-despised and suicidal Duke of Hawksmere seems at long last to have followed through with his oft-delayed promise to do himself in: “a good, straight-forward suicide,” thinks Chief Inspector Cockrill, “heralded by the gentleman himself….”

If only it were that simple. The dearly deceased, consistent with the burdensome pattern of his life, has managed to die under most perplexing circumstances that suggest he was murdered; to wit, he seems to have expired in a classic “locked room.”

Cockie, in frustration, says: “The locked room is the lodge, locked in, as it were in all that untrodden snow. A man dead in the lodge, very recently dead, death instantaneous, from a gun-shot wound at close range. And the mystery is very easy to state and not at all easy to answer. The mystery is — where is the gun? — because it isn’t lying there close to his right hand where it ought to be, and it isn’t anywhere else in the lodge and it isn’t anywhere outside in all the snow.”

As in “The Hornet’s Nest,” Cockie devises two plausible scenarios — but the actual solution, one not of his devising, comes as an exasperating — and exasperatingly simple — surprise to both him and the unsuspecting reader.

Note: “The Man on the Roof” can also be found in Thomas Godfrey’s English Country House Murders, 1989.

10. “Alleybi” (“This story, published in this volume for the first time, was probably written in the mid-1950s.”)

A short-short story (one and a half pages) that should serve as a warning to all investigating officers not to get tunnel vision whenever someone’s alibi is in doubt.

11. “The Spotted Cat: A Play in Three Acts” (“Previously unpublished; written in 1954-1955. Brand considered turning it into a novel but abandoned the idea.”)

Things aren’t going particularly well for barrister Graham Frere these days: His legal prowess is failing, he’s experiencing problems with alcohol, and he is beginning to think he’s going crazy.

At first he doesn’t realize that not all of his troubles are of his own making, that people close to him — under his very roof — are subtly pushing him towards madness, or possibly suicide; they have already murdered once, however, so even that option isn’t off the table. The conspirators themselves share a love-hate relationship, as evidenced by one telling the other:

“We’re bound together for ever now, you and I.”

“Nothing binds us.”

“Fear binds us.”

“It doesn’t bind me.”

and: “When I look at you — coldly and sanely — I’d as soon put my love and trust in a cobra.”

Nice people! But the conspiracy falters when the worm turns and murder is prescribed ….

This play is a mixture of Gaslight and Double Indemnity with just a dash of Patricia Highsmith. Brand spoofs herself in one exchange:

“London Particular was a book — that woman who wrote Green for Danger.”

“I know it was. I couldn’t read a word of it.”

Despite a few typos (e.g., “does” for “dose,” “desert” for “dessert”) and some problematic punctuation, this book can be highly recommended.

Sat 14 Mar 2009

A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

CHRISTIANNA BRAND – Heads You Lose. John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hc, 1941. US hardcover: Dodd Mead, 1942. Hardcover reprint: Ian Henry (UK), 1981. Paperback reprints include: Penguin (UK), several printings, 1950s; Bantam, June 1988 (shown).

Christianna Brand’s mystery output seems paltry compared to, say, Agatha Christie.

In the 1950s, Brand produced progressively less in the crime fiction field, focusing more on her children’s writing. According to the IMDb, a handful of her children’s stories were adapted for British TV and one was the subject of a full-length motion picture a few years ago.

Film makers gave her mystery fiction brief attention in the mid-to-late 1940s, and then she was promptly forgotten. Only Green for Danger (1946), based on her 1944 novel, seems to have been given a proper treatment. Film critic William K. Everson and yours truly agree that this movie is THE classic detective film, with The Kennel Murder Case vying with it for first place.

Thomas Godfrey, in his English Country House Murders (1989), characterizes our author and her writing thus: “Christianna Brand (Mary Christianna Milne Lewis), the last of the grandes dames of traditional English writing, was, like Josephine Tey, a connoisseur’s writer. Her plots are intelligently premeditated, rich in atmosphere, keenly observed, and subtly set forth.” (page 423)

Heads You Lose memorably introduces her series sleuth, Inspector Cockrill, like this:

“[He] was a little brown man who seemed much older than he actually was, with deep-set eyes beneath a fine broad brow, an aquiline nose and a mop of fluffy white hair fringing a magnificent head. He wore his soft felt hat set sideways, as though he would at any moment break out into an amateur rendering of ‘Napoleon’s Farewell to his Troops’; and he was known to Torrington and in all its surrounding villages as Cockie. He was widely advertised as having a heart of gold beneath his irascible exterior; but there were those who said bitterly that the heart was so infinitesimal and you had to dig so deep down to get to it, that it was hardly worth the trouble. The fingers of his right hand were so stained with nicotine as to appear to be tipped with wood.” (page 22)

Heads You Lose was, according to the bibliographies, Christianna Brand’s second book; and there are some rough places in the narrative that seem to show she isn’t quite as accomplished as she would later become. Nonetheless, compared to some other Golden Age writers of the same period, she often reads like Shakespeare.

Chapter 6, the coroner’s inquest, is a marvelous set piece filled with low comedy and not a little misdirection.

It isn’t revealing too much to say that Inspector Cockrill doesn’t really solve this case; he lets the other characters eliminate false trails on their own. It’s fun to watch one indolent character exerting himself trying to prove the guilt of another character — but what’s his motivation, to protect a woman or to shift suspicion from himself?

Cockie also spends a large part of the first half of the book off-stage and gradually assumes a greater presence later; also, we are allowed into his thoughts only intermittently — in fact we spend much of the book inside various other characters’ minds, including, believe it or not, the murderer’s (but without being conscious of it).

The story has a historical setting, a cosy English village not long after the Dunkirk evacuation, but the war is alluded to only in several places and never intrudes much into the narrative.

It’s annoying when Brand introduces an impossible crime but doesn’t do much with it — the impossibility is later dismissed in one sentence. But all the characters, major and minor, are well imagined.

Once she had hit her stride, Christianna Brand could play “The Grandest Game” with the best of them. Heads You Lose shows her warming up for her later, more solidly plotted novels in which she could often out-Christie Christie.