Search Results for 'Cornell Woolrich'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 19 Mar 2008

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

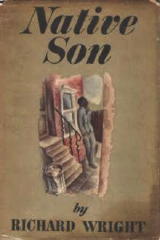

Richard Wright (1908-1960) was perhaps the best-known and most written-about black novelist of the 20th century, but as far as I know no one except myself has ever pointed out the debt he owes to Cornell Woolrich. During the late Thirties when Wright was working on his first and finest novel, Native Son (1940), he is known to have been a voracious reader of the pulp mystery magazines like Black Mask to which Woolrich contributed dozens of stories.

Native Son’s basic storyline of a young man wrongly accused of murder and running headlong through “streets dark with something more than night” was clearly inspired by Woolrich’s powerful suspense thriller “Dusk to Dawn” (Black Mask, December 1937; collected in Nightwebs, 1971).

During the last months of his life Wright was working on another crime novel, recently published in unfinished form as A Father’s Law, and it seems equally clear that here too he took his point of departure from Woolrich. In “Charlie Won’t Be Home Tonight” (Dime Detective, July 1939; collected in Eyes That Watch You, 1952) a middle-aged cop slowly becomes convinced that the criminal he’s seeking is his son. Woolrich’s cop of course is white. A Father’s Law deals with a middle-aged black cop who also becomes convinced that his son is a criminal.

If this is simply a double coincidence, it’s one that even Woolrich (who was prone to stretch coincidence to the outer limits) would have rejected. Any student of African-American literature who’s in need of an unexplored topic could do worse than to investigate the Woolrich-Wright interface in depth.

Silly mistakes in mystery fiction are not confined to nonentities like John B. Ethan, whose fond delusion that Zen Buddha was a person I discussed in my last column. Some of the biggest names have perpetrated howlers no less ridiculous.

Take, for instance, Margery Allingham. “The Definite Article” (The Strand, October 1937; collected in Mr. Campion and Others, 1950) finds Albert Campion called in by his friend Superintendent Oates when Scotland Yard is asked by the “Federal Police” of the U.S. (by which I presume she means the FBI) to arrest and deport a “society blackmailer” whose extortion drove a young woman in New York to suicide.

Excuse me? Where’s the Federal crime? Where’s the Federal jurisdiction? Any doubts that Allingham knew nothing about the American legal system should be allayed a little further in the story when Campion asks Oates why the Feds got in touch with Scotland Yard instead of, say, “the Sheriff of Nevada.” Since when do states have sheriffs?

Richard Fleischer (1916-2006) directed some of the worst big-budget movies ever to issue from Hollywood but started out helming several excellent little specimens of film noir, perhaps the best known being The Narrow Margin (1952) and Violent Saturday (1955).

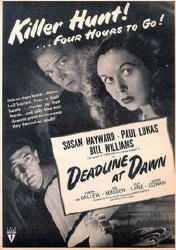

His memoir Just Tell Me When to Cry (1993) says very little about most of his noirs but includes a neat anecdote about a similar film he had nothing to do with. In 1946, as a novice at RKO, he sat in on a production meeting with tough-as-nails executive producer Sid Rogell and the well-known theatrical director Harold Clurman, who was helming his first movie. Fleischer doesn’t name the picture but, since Clurman made only one movie in his life, it has to be Deadline at Dawn, loosely based on Cornell Woolrich’s novel of the same name.

As Fleischer remembered the meeting, the first thing Rogell told Clurman was: “You don’t have forty days to shoot the picture. You’ve got thirty.” Then Rogell picked up the script, noticed that the first scene took place at night and called for rain (in film noir, what else?) and asked Clurman: “Rain? You know how much fucking rain costs?….What do you want rain for?” “For the mood,” Clurman told him. “Fuck the mood. No rain.”

Rogell was about to order Clurman to cut back on the number of people who appeared in the scene when the director interrupted: “How about dust? Lots of dust blowing everywhere. Can we afford dust?”

In the finished film the first scene takes place indoors – the confrontation between the blind pianist (Marvin Miller) and his predatory ex (Lola Lane) – and neither rain nor dust appears in the second scene, which is set outdoors but was clearly shot on a soundstage.

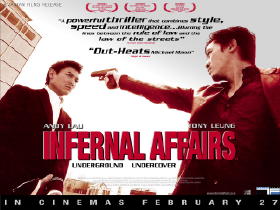

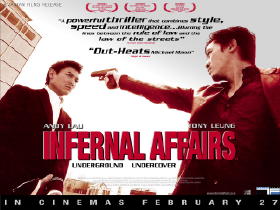

So many people have told me that I absolutely must see Infernal Affairs (2002), the Hong Kong movie which Martin Scorsese remade with Leonardo di Caprio and Matt Damon as The Departed, that I finally did it earlier this month.

The Asian film tells the same story as its U.S. counterpart – the duel between two moles, one planted in the mob years ago by the PD, the other planted in the PD by the mob – but much more tightly and cynically and without the graphic in-your-face violence that seems to have become a Scorsese trademark.

If you’ve hesitated because you’re unfamiliar with Asian action films and are afraid you won’t be able to tell the characters apart, I can assure you that this is not a problem. The wispy-mustached police mole in the mob (Tony Leung) could never be confused with the clean-shaven mob mole on the force (Andy Lau), and the only cop whose knows his mole’s identity (Anthony Wong) could no more be mistaken for the only mobster who knows his mole’s identity (Eric Tsang) than could Martin Sheen for Jack Nicholson in Scorsese’s version.

I do recommend, however, that Infernal Affairs be seen in letterbox. The panned-and-scanned version I got from Netflix eliminates far too much of each image from an intensely visual film – and one that goes far towards proving that noir has become a universal language.

Tue 4 Sep 2007

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

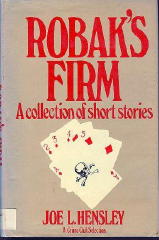

Late August was a disaster for mystery writers and lovers. First we lost Magdalen Nabb, then John Gardner, then one who was a dear friend of mine. Joe L. Hensley � private attorney, member of the Indiana legislature, prosecutor, judge, dealer in rare coins and paper money, writer of science fiction since the early 1950s and more recently of 20-odd mystery novels � died on August 27 at age 81.

For the past several decades his home was Madison, Indiana, a charming town on the Ohio River just across from Kentucky and about 300 miles from St. Louis. Whenever I was driving east he’d invite me to stay over for drinks, dinner, dialogue and the use of his guest bedroom. How he could tell stories! Hoosier politics, the judiciary, colleagues in the SF and mystery fields ranging from Harlan Ellison to Avram Davidson to John D. MacDonald, encounters over the years with everyone from Robert Frost to Bob Hope — the anecdotes poured out of him like the water over Niagara Falls, especially when we’d drive together from Madison to the annual Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio, where he was guest of honor one year and I the next.

I reviewed several of his novels for St. Louis newspapers and wrote the entry on him for the reference book that used to be called 20th Century Crime and Mystery Writers and is now for obvious reasons known as the St. James Guide to Crime and Mystery Writers. His final novel, Snowbird’s Walk, will be published early next year. Driving east will never again be so pleasant for me.

The Indiana towns I know best are Madison, thanks to Joe, and Bloomington, thanks to Indiana University’s Lilly Library where Anthony Boucher’s papers are archived. On a visit to the Lilly several years ago I came upon Boucher’s correspondence with Cornell Woolrich and his comments on various Woolrich stories. Someday I hope to include this material in an updated edition of First You Dream, Then You Die, but this column offers a fine venue for a sneak preview.

In Tony’s first letter to the master of suspense, dating from the late spring of 1944, he asked permission to reprint a Woolrich tale in his anthology Great American Detective Stories (World, 1945). Replying on June 5, Woolrich recommended that Boucher use “Endicott’s Girl” (Detective Fiction Weekly, February 19, 1938), which he called “my favorite among all the stories I’ve ever written.”

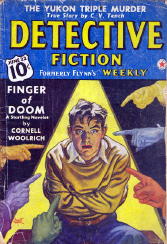

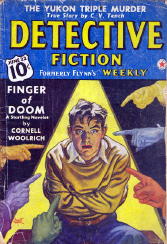

Boucher didn�t care for that one, as he explained in a July 19 letter to World editor William Targ: �It has in extreme measure the frequent Woolrich flaw � a fine emotional story which ends with loose ends all over the place and nothing really explained.� Instead Boucher opted for �Finger of Doom� (Detective Fiction Weekly, June 22, 1940), which he retitled �I Won�t Take a Minute.� �Endicott�s Girl� remained uncollected until I put it in Night and Fear (2004).

More gems from the Boucher-Woolrich correspondence are likely to pop up in future columns.

The first murder in Rex Stout�s Over My Dead Body (1940) takes place in a fencing academy. The weapon is a col de mort, a doohickey that when slipped over the usually blunt end of an epee turns it into a lethal weapon. Whether Stout made up this device out of whole cloth (if I may coin an Avalloneism) or whether it exists in the real world I have no idea and couldn�t care less. What intrigues me is whether among the readers of this Nero Wolfe adventure might have been one J.K. Rowling. Is it coincidence that the king toad of the Harry Potter books is named Lord Voldemort?

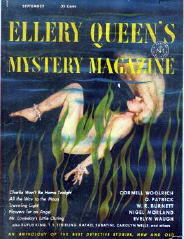

Vincent Cornier (1898-1976) was an English author of French descent who inherited a neat pile of money as a young man and thereafter devoted himself to writing short stories of fantasy and mystery. Very few of them were published in the U.S. until, after World War II, Fred Dannay discovered his work in old British periodicals and began reprinting occasional Cornier stories in Ellery Queen�s Mystery Magazine.

Eventually Cornier began to send Fred a few originals. Earlier this year I had occasion to re-read most of his stories from EQMM. The one I found most intriguing was the first of those originals, �O Time, In Your Flight� (September 1951).

Why? Because it contains a uniquely beautiful clue to the solution: one that is available only to readers who recognize the title�s poetic source and remember the three words in the poem that come just before the five in the title! The question all but asks itself: Was it Cornier or Fred who put that brilliant title on the story? Their correspondence, which is archived at Columbia University, doesn�t indicate what title was on the tale when Cornier submitted it, but we know that Fred had a penchant for changing the titles of many of the stories he published. Also I find no evidence in Cornier�s other stories that he had any particular interest in poetry, while Fred not only collected rare first editions of poetry but also wrote some of his own. It seems to me far more likely than not that the stroke of genius was Fred�s.

If further proof is needed, there�s indisputable evidence that Fred knew the poem in question: he used the first three words of the line, the words that provide the clue to Cornier�s story, as the title for another tale by another author that appeared in EQMM a few years later! The author was Dorothy Salisbury Davis, the issue June 1954. After you�ve read �O Time, In Your Flight� in Duels in Shadows, the forthcoming Crippen & Landru collection of Cornier�s best mysteries, Google the title and you�ll quickly find what I�ve been hinting at without, I hope, having given it away. But don�t do it before or you may spoil the story!

Fri 10 Jun 2022

CORNELL CLUB:

The Woolrich Adaptations of François Truffaut

by Matthew R. Bradley

It is no surprise that the term film noir is French, given how avidly Gallic filmmakers and/or critics (some were both) embraced what we now know as noir fiction and its cinematic counterpart, or that they turned to the former as source material. The novels of David Goodis, for example, were adapted into not only the Bogart/Bacall vehicle Dark Passage (1947) but also the likes of François Truffaut’s Tirez sur la Pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player, 1960), based on Down There (1956); Henri Verneuil’s Le Casse (aka The Burglars, 1971), based on The Burglar (1953), filmed Stateside in 1957; and La Lune dans le Caniveau (The Moon in the Gutter, 1983), directed by Diva (1981) phenom Jean-Jacques Beineix.

While Henry Farrell may be best known as the original author of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1960), and thus the “Godfather of Grande Dame Guignol,†Truffaut’s 1972 adaptation of his 1967 novel Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me (aka Une Belle Fille comme Moi [A Gorgeous Girl Like Me]) is surely noir, and Truffaut also filmed two books by the arguably definitive noir writer, Cornell Woolrich: The Bride Wore Black (1940), part of his celebrated series of “Black†Novels, and Waltz into Darkness (1947), published under his pen name of William Irish.

Made in England, Truffaut’s controversial 1966 version of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) had been a considerable departure, his first film in English and in color and his only SF effort, shot by future director Nicolas Roeg rather than usual cinematographer Raoul Coutard. But he was back on his literal and metaphorical home turf with La Mariée Etait en Noir (The Bride Wore Black, 1967), shooting in France and adapting another noir novel with familiar faces both behind the camera (Coutard and co-scenarist Jean-Louis Richard) and in front (Jeanne Moreau, Jean-Claude Brialy).

The legendary book-length interview Hitchcock/Truffaut (1966) had recently been published, and the fact that the Master of Suspense’s Rear Window (1954) was also based on Woolrich story is one aspect that makes this perhaps Truffaut’s most Hitchcockian work, as is carrying over composer and Hitch mainstay Bernard Herrmann from Fahrenheit in their second and final collaboration.

The film is basically a quintet of set pieces in each of which the title character, Julie Kohler (Moreau), kills a man, making sure he knows her identity, e.g., she pushes Bliss (Claude Rich) from his balcony during a party when he tries to retrieve her windblown scarf; lures Coral (Michel Bouquet) to a rendezvous where she poisons him; and leaves Rene Morane (Michel Lonsdale) to suffocate in a sealed closet while his son, Cookie (Christophe Bruno), slumbers upstairs.

Flashbacks gradually reveal that she is avenging the death of her childhood sweetheart, David (Serge Rousseau), shot dead on the church steps after their wedding as the five fooled around with a loaded rifle across the street. The film addresses neither how Julie tracks down the men — strangers drawn together on a single occasion, sharing only a predilection for guns and women (the latter ultimately their undoing), who fled, never to meet again — nor whether David’s accidental killing justifies theirs.

Julie clearly has her own idea of justice, leading her to call the police and clear Cookie’s teacher, Miss Becker (the striking Alexandra Stewart), as whom she posed, by providing details only the killer could know.

I don’t know how, or even if, the novel tackles any of these questions, yet in a sense, it doesn’t matter; we don’t turn to Cornell Woolrich for rigorous logic but for his fever-dream imagination and style, and Truffaut himself, obviously interested more in the effect than in explanations, begins to play with our expectations as Julie’s next target, Delvaux (Daniel Boulanger), is suddenly arrested for unrelated crimes, so she turns to the last on her list, artist Fergus (Charles Denner).

When she begins posing for him as the bow-wielding huntress (how apt!) Diana, we suspect how he will meet his end, yet for the first time, she seems hesitant after Fergus, anticipating Denner’s role as Truffaut’s L’Homme Qui Aimait les Femmes (The Man Who Loved Women, 1977), avows his amour.

It is around this point that Truffaut uses maximum cinematic sleight of hand, misdirecting us with a subplot about how Fergus’s friend Corey (Brialy) remembers seeing Julie at Bliss’s party and tries to identify her.

Having watched in step-by-step detail as she dispatched each of her previous victims, we are genuinely surprised when Truffaut abruptly cuts back to Fergus lying dead with an arrow protruding from his body, and even more so when the seemingly relentless avenger leaves an incriminating mural of herself on the wall, which along with her attending the artist’s funeral leads to her arrest and confession, albeit without explanation.

But — as my first-time-viewer wife quickly deduced — it is all a means to an end, and as Julie, with knife concealed, delivers meals to inmates of the same prison where Delvaux is confined, we await the inevitable off-screen shriek as she finishes her mission.

Asked by Le Monde in 1968 if Hitchcock had influenced the film, the director said, as quoted in Truffaut by Truffaut (*), “Certainly for the construction of the story because, unlike the novel, we give the solution of the enigma well before the end [as in Hitch’s Vertigo (1958)]…. Contrariwise, the desire to make the characters speak of everything else but the intrigue itself is decidedly not very Hitchcockian and more characteristic of a European turn of mind.â€

In 1978, he called it “the only one I regret having made… I wanted to offer…Moreau something like none of her other films, but it was badly thought out. That was a film to which color did an enormous lot of harm. [A permanent rift with Coutard reportedly left Moreau sometimes directing the actors.] The theme is lacking in interest: to make excuses for an idealistic vengeance, that really shocks me…. One should not avenge oneself, vengeance is not noble. One betrays something in oneself when one glorifies that,†as he opined to L’Express.

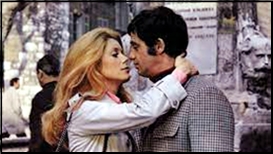

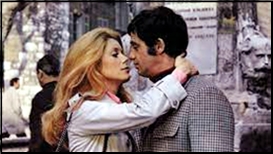

Truffaut’s Woolrich adaptations were made with only one film (my personal favorite of his), Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses, 1968), in between; the fatalistic nature of the second, Mississippi Mermaid (1969) — whose title seems more appropriate in French, La Sirène du Mississippi, given the sinister connotations of “siren†— makes it not too surprising that, per New York Magazine critic David Edelstein’s TCM introduction, it was his biggest financial failure, but I think it deserved better.

The first of his features on which Truffaut had sole screenwriting credit, it updates Woolrich’s 1880 New Orleans setting to the contemporary French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, to which the ship Mississippi brings a woman (Catherine Deneuve) claiming to be Julie Roussel, the mail-order bride of Louis Mahé (Jean-Paul Belmondo, whom I have loathed since seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal French New Wave debut, À Bout de Souffle [Breathless, 1960]). She doesn’t match the photo that Julie had sent him, but Louis clearly falls for her at first sight and marries her anyway.

She says she sent a photo of a neighbor to ensure that Louis did not marry her for her looks, while he wrote that he was the foreman and not the owner of a cigarette factory, because he did not want to be married for his money. After “Julie†cleans out his bank accounts and disappears, Berthe Roussel (Nelly Borgeaud) arrives, and we learn that her sister was murdered aboard the ship by Richard (Roland Thénot), who later abandoned accomplice Marion Vergano, so they hire private detective Comolli (Bride alumnus Bouquet) to find the impostor.

In France, Louis spots Marion in some news footage — precisely paralleling D’Entre les Morts (From Among the Dead, 1954) by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the source novel for Vertigo — then locates and confronts her, but is unable to kill her; Louis shoots Comolli when he gets too close and refuses to take a bribe, and the couple’s peripatetic future as fugitives seems bleak, despite Louis forgiving Marion for trying to poison him and her declaration of love.

When I saw this for the second time (c. 2014), the first being in the 1999 “Tout Truffaut†retrospective at the hallowed ground of New York’s Film Forum, it seemed surprisingly familiar. It’s true that at various times I have also read Waltz into Darkness (I was honored to be asked to weigh in on whether Viking Penguin, where I was then employed, should reissue it, which they did) and seen the 2001 remake, Michael Cristofer’s Original Sin, notorious for its steamy scenes between Antonio Banderas and Angelina Jolie — talk about something for everyone — but I think there’s more to it than that, perhaps something distinctively Woolrichian.

His future biographer, Francis M. Nevins, Jr., wrote in Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers that “love dies while the lovers go on living, and [he] excels at showing the corrosion of a relationship between two people,†plus the theme of imposture recurs in I Married a Dead Man (1948), also filmed in France as J’ai Éspousé une Ombre (I Married a Shadow, 1983), starring Nathalie Baye.

“I read [the novel] when I was doing the adaptation of The Bride Wore Black,†Truffaut told Le Monde in 1969. “At that time, I actually read everything [he] wrote in order to steep myself in his work and to keep as close as possible to the novel, despite the unfaithfulness necessary in films. I like to know thoroughly any writer whose book I transpose to the screen [as he had with Goodis and Bradbury]…. My final screenplay was less an adaptation in the traditional sense than a choice of scenes. With this film, I was finally able to realize every director’s dream: to shoot in chronological order a chronological story that represents an itinerary…. [The] shooting began on Réunion Island, continued in Nice, Antibes, Aix-en-Provence, Lyons, to finish in the snow near Grenoble. The fact of respecting the chronology permitted me to ‘build’ the couple with precision….The Mermaid is above all else the tale of a degradation through love, of a passion.â€

(*) Text and documents compiled by Dominique Rabourdin; translated from the French by Robert Erich Wolf (New York: Abrams, 1987).

___

Portions of this article originally appeared on Bradley on Film.

Thu 1 Dec 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

LAWRENCE BLOCK – Deadly Honeymoon. Macmillan, hardcover, 1967. Paperback reprints include: Dell, 1969; Jove, 1986; Carroll & Graf, 1995. Filmed as Nightmare Honeymoon (1974).

Transplant Cornell Woolrich into a more permissive decade, and you would have this book, first published in hardcover in 1967.

A young attorney and his bride go to a remote Pennsylvania cabin for; their honeymoon, but it is interrupted by rape and murder. In this brutal but extremely suspenseful novel, a manhunt is generated by a desire for revenge with which the reader can easily identify.

ANNE CHAMBERLAIN -The Tall Dark Man. Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1955. Paperback reprints include: Dell #925, 1956; Avon Classic Crime PN322, 1970; Academy Chicago, 1986.

The plot of this 1955 mystery, reprinted in an especially attractive edition, is decidedly Woolrichian. A thirteen year-old girl says she has seen a murder through the window of her Ohio school room, but no one will believe her. She also claims that the murderer saw and recognized her.

When Anthony Boucher originally reviewed this book, he paid it the extravagant praise of saying “This is purely and absolutely, The Suspense Novel, in an ideal form, which the genre rarely attains.” He did not exaggerate very much.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 8, No. 4, July-Aug 1986.

Sun 26 Oct 2008

BOUCHER ON WOOLRICH:

WHEN TITANS TOUCHED

by Francis M. Nevins

Previously on this blog:

PART I. THE NOVELS.

PART II. THE STORY COLLECTIONS.

Part III. LETTERS, A CARD AND A MEETING.

Boucher wrote Woolrich for the first time in the late spring of 1944, requesting permission to reprint a story in his anthology Great American Detective Stories (World, 1945). Replying on June 5, Woolrich recommended that Boucher use the 1938 “Endicott’s Girl,” which he called “my favorite among all the stories I’ve ever written.”

Boucher didn’t care for that one, as he explained in a July 19 letter to World editor William Targ: “It has in extreme measure the frequent Woolrich flaw – a fine emotional story which ends with loose ends all over the place and nothing really explained.”

Instead Boucher opted for “Finger of Doom” (1940), which he retitled “I Won’t Take a Minute.” The new title was retained when the story was included in The Ten Faces of Cornell Woolrich (1965). “Endicott’s Girl” remained uncollected until I put it in Night and Fear (2004).

On July 20, one day after his letter to Targ, Boucher wrote Woolrich again: “In the past month or two I’ve read over 30 [of your] pulp stories. And even from such a dose as that I still feel no indigestion; which means, I take it, that you are (as I have suspected all along) the goods. Keep ’em coming!”

Woolrich’s reply, dated July 23, solved a puzzle for me. I had long suspected that his “The Penny-a-Worder” (1958; first collected in Nightwebs, 1971), which is about a pulp writer who has to hack out a story overnight to go with an already completed front cover illustration, was based on personal experience.

After finding the July 23 letter among Boucher’s papers at the Lilly Library I knew it for a fact. In it Woolrich mentioned that he particularly remembers his story “Guns, Gentlemen” (1937; collected as “The Lamp of Memory” in Beyond the Night, 1959) “because I wrote it to match up with the cover of the magazine, which they sent me.” This doesn’t mean, of course, that he wrote the story in a single night!

On a file card dating from 1950 or early 1951, when he was co-editing The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Boucher set down his reaction to the idea of reprinting Woolrich’s novella “Jane Brown’s Body” (1938). “This brilliantly macabre concept spoiled for me by 2 things: a.) My pet irritation of writing exclusively in present tense; b.) A pulp plot so formulaly obvious that each step can be accurately forecast. Inept, for Woolrich, but because of his name let’s include.”

It was reprinted in the magazine’s October 1951 issue and collected in The Fantastic Stories of Cornell Woolrich (1981).

Boucher finally met Woolrich while on a visit to New York in April 1965. He died without writing about the encounter but his widow, Phyllis White, was present and described it for me before her own death:

“[W]e were in a restaurant with some MWA members after a private viewing of a film…. Clayton Rawson [then managing editor of EQMM] told us that before going home he was going to drop in on Cornell Woolrich, who was convalescing from surgery, and he suggested that we come along.

“Of course Tony was thrilled at the prospect. We went to the hotel room where Woolrich was temporarily quartered. One eye had been operated on and he was to go back after an interval for an operation on the other. [Saint Mystery Magazine editor] Hans Santesson was there trying to look after him. He was supposed to go easy on drinking so he was sticking to wine. Santesson kept suggesting pleasantly but ineffectively that he slow down.

“The room had until recently been used for storage of furniture. It was in good enough condition except for lacerated wallpaper. Woolrich complained that the hotel staff was sneering and laughing at him behind his back. Rawson asked Woolrich whether he had anything lying around that would be suitable for reprint in EQMM.

“Woolrich rummaged around and turned up something. There was a bit of comic pantomime in which Rawson started to look at the story and then tried to hide it from rival editor Santesson peering over his shoulder.

“The only dramatic incident of the evening was missed by Rawson, who had to leave to catch his train. The door opened suddenly and a crowing man burst in with a girl and a bottle. The hotel had mistakenly sent him to that room and he was indignant on finding us there…

“The intruder withdrew, leaving Woolrich convinced that this was another part of the conspiracy against him. Eventually we left but it wasn’t easy. Woolrich thought that people who went away, no matter how long they had stayed, were leaving because they didn’t like him. Tony was delighted that he had finally met Woolrich, and at the same time thought that it wouldn’t do his own nerves any good to see too much of him… ”

He needn’t have worried. They never met again. Boucher died of lung cancer on April 29, 1968, at the unbearably early age of 56; Woolrich of a stroke on September 25, a little more than two months before his 65th birthday. Just a few months apart. Forty years ago this year. May they rest in peace.

Wed 22 Oct 2008

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

ReviewsNo Comments

BOUCHER ON WOOLRICH:

WHEN TITANS TOUCHED

by Francis M. Nevins

Previously on this blog: PART I. THE NOVELS.

PART II. THE STORY COLLECTIONS.

The first collection of Woolrich’s shorter work was I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (1943, as by William Irish), which includes at least three supreme classics: the title story (1938) plus “Three O’Clock” (1938) and “Nightmare” (1941, as “And So to Death”).

Boucher inexplicably didn’t review the book but late in December he listed it as the year’s best volume of crime fiction at less than novel length. It was also the only such collection published that year, but clearly Boucher didn’t include it among 1943’s best by default, since a few months later (28 May 1944) he called it one of the 13 finest books of short crime fiction published since 1920.

The follow-up volume After-Dinner Story (1944, as by William Irish) brought together six tales of which at least four — the title story (1938), “The Night Reveals” (1936), “Marihuana” (1941) and “Rear Window” (1942, as “It Had To Be Murder”) — are among Woolrich’s most powerful. Boucher found one or two of the half dozen (apparently the ones I didn’t name) “a bit too patly ironic” but called the others “first-rate specimens of that master of the suspense and terror of the commonplace.” (26 November 1944)

If I Should Die Before I Wake (1945, as by William Irish) was a digest-sized original paperback collection of six tales of which three are pure gems: the title story (1937), “A Death Is Caused” (1943, as “Mind Over Murder”), and “Two Murders, One Crime” (1942, as “Three Kills for One”).

Boucher, perhaps the only critic broad-minded enough to notice softcover originals, described the 25-cent volume as “various in quality but containing at least two of the finest Woolrich-Irish opuses — which is about as fine as terror-suspense comes currently.” (1 July 1945) When the collection was reissued as a paperback of conventional dimensions a year and a half later, Boucher said that “to watch the Old Master of suspense technique at work is worth anybody’s two bits.” (19 January 1947).

Next came The Dancing Detective (1946, as by William Irish), which contained eight stories, four of them top-drawer noir: the title story (1938, as “Dime a Dance”), “Two Fellows in a Furnished Room” (1941, as “He Looked Like Murder”), “The Light in the Window” (1946) and “Silent As the Grave” (1945). Boucher praised the book to the skies: “Nightmares of a…masochistically pleasant nature await the reader who recognizes in [Woolrich] the great living master of what the psalmist calls “the noonday devil” — the infinite terror of prosaic everyday detail.” (14 July 1946)

The last Woolrich collection Boucher reviewed for the Chronicle was Borrowed Crime (1946, as by William Irish), another digest-sized paperback original costing a quarter then and worth a mint today. This one brought together four short novels, two of them dispensable, the other pair — “Detective William Brown” (1938) and “Chance” (1942, as “Dormant Account”) — displaying Woolrich at his most powerful. Boucher’s review was terse but just: “The excellence of the Woolrich-Irish pulp novelettes is now so widely recognized that the mere announcement of this latest collected volume should send you scurrying to a newsstand.” (9 March 1947).

Six more Woolrich collections, all as by William Irish, were published over the next six years. The first two came out when Boucher was off the Chronicle and not yet on the Times, but he praised both in his “Speaking of Crime” column for EQMM:

Dead Man Blues (1947) brought together seven tales including the classics “Guillotine” (1939, as “Men Must Die”) and “Fire Escape” (1947, as “The Boy Cried Murder”). Boucher called the collected stories “a compelling group….” (February 1949)

The Blue Ribbon (1949) gathered eight more tales of which by far the finest was the nonstop action thriller “Subway” (1936, as “You Pays Your Nickel”). Boucher described the octad as “a mixed lot ranging from the supernatural to pure sentimental emotionalism. But the five crime stories included bear the authentic Woolrich/Irish stamp so unmistakably that no seeker of suspense can afford to overlook the volume.” (August 1949)

He was no longer reviewing for EQMM when the next Woolrich collection was published. Somebody on the Phone (1950) was reviewed in the Times but not by Boucher. The subsequent paperback-original collections Six Nights of Mystery (1950) and Bluebeard’s Seventh Wife (1952) were reviewed by no one.

But Boucher made it a point to discuss what turned out to be the final collection under the Irish byline. Eyes That Watch You (1952) included seven stories. Its three longer tales — the title story (1939, as “The Case of the Talking Eyes”) plus “Charlie Won’t Be Home Tonight” (1939) and “All at Once, No Alice” (1940) — Boucher praised as “richly representing [Woolrich’s] best work.” The other four, which were much shorter, he dismissed as “minor gimmick stories which any hack could have written” but he advised readers to “overlook them, settle down to the longer stories and revel in the skill of the foremost master of the breathtaking this-could-happen-to-me impact.” (24 August 1952)

All subsequent Woolrich collections were published under his own name. Nightmare (1956), a volume of six tales including two classics previously collected in I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes, gave the critic a chance to sum up his ambivalence about the author:

“By sober critical standards there is just about everything wrong with much of Woolrich’s work. This collection of six stories illustrates most of the flaws: the ‘explanation’ that is harder to believe than the original ‘impossibility,’ the banal and over-obvious twist of ‘irony,’ the casual disregard of fact or probability –the Los Angeles Police Department so understaffed that only a single investigator of low rank can be spared to handle the murder of a film star! However, critical sobriety is out of the question so long as this master of terror-in-the-commonplace exerts his spell. It is an oddly chosen collection, representing neither the best nor the least familiar of Woolrich … but it is characteristic, and I do not envy the hard-headed reader who can resist its compulsive black magic.” (2 September 1956).

Of the six tales printed in the sequel collection Violence (1958), I would rank three with Woolrich’s best: “Don’t Wait Up for Me Tonight” (1937, as “Goodbye, New York”), “Guillotine” (1939; previously collected in Dead Man Blues, 1947), and “Murder, Obliquely” (a heavily revised version of “Death Escapes the Eye,” 1947). “Guillotine” was the only one of the six that in Boucher’s view “ranks with the best of Woolrich’s unforgettable pulp classics.” But all six, he said, “display, if to a lesser extent, [Woolrich’s] mastery of detail in creating tension and terror out of the commonplace.” (10 August 1958).

About a month later Woolrich’s Hotel Room came out. The setting is Room 923 of New York’s Hotel St. Anselm and the story of the building’s birth, adolescence, maturity, old age and death is told through the stories of the people who checked into that room at various points in time between 1896 and the late Fifties. The book wasn’t reviewed in the Times at all but Boucher devoted a few lines to it in his monthly column for EQMM, calling it “less a novel than a collection of episodes, many with the impact of [Woolrich’s] crime shorts.” (November 1958) A most generous comment considering that only one episode in the book was even remotely criminous!

The next Woolrich collection was the paperback original Beyond the Night (1959), which Boucher covered in the Times at much greater length:

“Recent Woolrich collections have, I suspect, been selected by the author himself; they seem to consist largely of those stories best loved by their creator because no one else appreciates them. Beyond the Night contains six stories, mostly supernatural, including [in “My Lips Destroy” (1939, as “Vampire’s Honeymoon”] the most tedious arrangement of cliches on the vampire theme ever assembled. There are glints of the old Woolrich magic, especially in a 1935 tale of voodoo [“Music from the Dark,” better known as “Papa Benjamin”] and a 1959 picture of gang callousness [“The Number’s Up”], but there are so many much better Woolrich stories which have yet to appear in book form.” (4 October 1959)

The following year saw the publication of Woolrich’s last paperback original, The Doom Stone (1960). Boucher described it superbly as “heaven help us, about the diamond stolen from the eye of a Hindu idol in 1757 and the curse it brings on successive owners in Paris during the Terror, in New Orleans under the carpetbag regime and in Tokyo just before Pearl Harbor. Few authors would dare make a straight-faced offer of such triple-distilled corn, but devout Woolrichians (like me) may find it surprisingly potable if hardly intoxicating.” (8 May 1960)

By then Woolrich was dying by inches and writing very little. Boucher had no occasion to discuss him again until five years later when the final collections of Woolrich’s lifetime appeared roughly three months apart.

Of The Ten Faces of Cornell Woolrich he said: “Much though I admire the work of [Woolrich], I can see little excuse for [this collection]. Eight of the ten stories have appeared in book form before, six of them in earlier gatherings of Mr. Woolrich’s tales. (One indeed is making its third appearance in a Woolrich collection.) The stories, to be sure, range from good to excellent, but this can hardly claim to be a new $3.95 book.” (2 May 1965).

The Dark Side of Love Boucher described as bringing together “several of [Woolrich’s] lesser recent short stories along with others which seem, for good reasons, not to have appeared in magazines. It’s a collection that stresses this veteran’s weaknesses rather than his virtues, but at least only one of its eight stories has been published in an earlier Woolrich volume. Only the previously unpublished “Too Nice a Day to Die” seems to me to rank with Woolrich’s best.” (25 July 1965)

Coming soon:

PART III: LETTERS, A CARD AND A MEETING.

Mon 6 Oct 2008

Posted by Steve under

Authors ,

Reviews1 Comment

BOUCHER ON WOOLRICH:

WHEN TITANS TOUCHED

by Francis M. Nevins

They died just a few months apart, forty years ago this year, and each is still considered the gold standard in his domain, Anthony Boucher in commentary on mystery fiction, Cornell Woolrich in nightmarish suspense. What did Boucher make of Woolrich and his work? I hope to address that question here.

PART I. THE NOVELS.

Boucher’s first detective novel, The Case of the Seven of Calvary, came out in 1937; his last two, The Case of the Seven Sneezes and Rocket to the Morgue (as by H.H. Holmes), in 1942. Late in October of that year he took over as mystery critic of the San Francisco Chronicle from Edward Dermot Doyle, who had joined the military after Pearl Harbor.

By then Woolrich had published well over a hundred crime-suspense stories in the leading pulp magazines plus his first four suspense novels: The Bride Wore Black (1940), The Black Curtain (1941), Black Alibi (1942), and Phantom Lady (1942, as by William Irish).

Boucher was clearly familiar with Woolrich’s work before he reviewed The Black Angel, of which he said: “Even Mr. Woolrich has never written a tenser, more jolting novel….” (21 February 1943). Ten months later he described the book as a classic of the ‘school of pure terror’ and listed it among the year’s best crime novels (26 December 1943).

Reviewing Deadline at Dawn, the second novel to appear under the William Irish byline, Boucher called it Woolrich’s “most contrived and least believable story yet, and still magically exciting almost against one’s judgment.” (5 March 1944).

That summer he was equally ambivalent about Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear, much of which is set in Havana. “The consciously colorful atmosphere robs this of some of the impact Woolrich can get from drab American cities, but it’s nonetheless exciting.” He was bothered however by what he called the novel’s “frank glorification of revenge-killing.” (18 June 1944)

Woolrich published two more novels during Boucher’s years on the Chronicle. For some unknown reason he didn’t review Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945, as by George Hopley). He did write up Waltz into Darkness (1947, as by William Irish) but I couldn’t establish that his review was ever published and therefore left it out of The Anthony Boucher Chronicles, my collection of his journalism for that paper.

The carbon copy survives and is among his papers preserved at Indiana University’s Lilly Library. Waltz has never been one of my favorite Woolrich novels and I gather it wasn’t one of Boucher’s either. He described its protagonist Louis Durand as an “ordinarily decent man who, sexually obsessed by an unprincipled woman, sinks ever deeper into crime and destruction” but contended that Woolrich gave this theme a rather “conventional treatment, romantically betrapped and ‘redeemed’ by a sentimental conclusion.”

On the other hand, he said, Woolrich’s “familiar skill is highly in evidence here – he can still make suspense all but unbearable, and invest the everyday with sinister terror. You won’t soon forget the scene of the real estate agent showing a prospect over the house – with the grave not yet tamped down.”

In the last analysis however he wrote off Waltz into Darkness as “a Class A production in glorious Technicolor with a glamorous cast – as it will doubtless (and deservedly) become.” In fact Waltz was one of only three Woolrich novels of the Forties not to be adapted into a movie – in any event not until shortly after both Boucher and Woolrich died, when it became the basis of Francois Truffaut’s intriguing if not terribly Woolrichian La Sirene De Mississippi (1968), with exactly the kind of glamorous stars Boucher had predicted (Jean-Paul Belmondo and Catherine Deneuve) in the leading roles.

Woolrich’s last major novels, I Married a Dead Man (as by William Irish) and Rendezvous in Black, were published in 1948. By then Edward Dermot Doyle had returned to civilian life and reclaimed his slot on the Chronicle. Since Boucher hadn’t yet made his connection with the New York Times, those novels were reviewed there by others.

Boucher did however mention Rendezvous in the first of his short-lived “Speaking of Crime” columns for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, calling it “pure black magic… – and if it’s a rewrite of his first book-form mystery story [The Bride Wore Black], who’s complaining?” (February 1949)

Of the first three Woolrich novels published after Boucher began writing for the Times, he ignored Savage Bride (1950), a paperback original and the only one of the trio to come out under Woolrich’s own name, while another reviewer wrote up Strangler’s Serenade (1951, as by William Irish). But Boucher had much to say about Fright (1950, as by George Hopley):

“No one could read a dozen pages … without recognizing the authentic Woolrich mastery of the terror of the everyday-gone-wrong; nor could one read all 245 pages without also recognizing the equally authentic Woolrich falsification of plot for the sake of a facile irony, with a few unexplained coincidences left over. Though this flaw constantly arises infuriatingly to prevent consideration of Woolrich as a serious novelist, there is no one mystery story writer more adept at suggesting the small uncertain terrors of life and the evil latent in drab characters. This 1915 period piece concerns a clerk goaded into murder on the morning of his wedding and forced deeper and deeper into self-destruction by his obsession to destroy the things that imperil him.” (12 February 1950)

The last genuine novel Woolrich completed and published during his lifetime was the paperback original Death Is My Dancing Partner (1959), a disaster which Boucher mercifully never mentioned. The following year saw publication of The Best of William Irish, an omnibus volume reviving the novels Phantom Lady and Deadline at Dawn and the collection After-Dinner Story.

Boucher was enthusiastic as only Boucher could be. “Although the complete ‘Best’ of Irish-Woolrich would run to at least three more volumes of this size, these will do as terrifying plunges into the vertiginous world of nightmare below the surface of everyday life.” (13 March 1960).

The last Woolrich suspense novel that Boucher discussed was the first in point of time. The 1964 paperback reissue of The Bride Wore Black (1940) begins with an introduction in which the foremost mystery critic of his time (or since) summed up the achievements of the genre’s master of suspense. “He is personally something of a recluse and a mystery. No one in the profession knows him intimately, and everyone who knows him at all takes on a slightly dazed look when his name is mentioned.”

Boucher refused on principle to summarize Bride’s plot but called it “my favorite among his book-length stories … purest essence of Woolrich, sounding like no one else in the business.”

Coming soon:

PART II: THE STORY COLLECTIONS.

PART III: LETTERS, A CARD AND A MEETING.

Mon 16 Jul 2007

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Whenever I visit a foreign-language website and click the mouse for an electronic translation, I am reconfirmed in my judgment that of all the Ed Woods of the written word whose genius for mangling the language has enriched my reading life for decades, my computer is second to none.

May I give a for instance? Night and Fear, a collection of stories by Cornell Woolrich that I put together a few years ago to celebrate the centenary of his birth, was recently published in Italian by Feltrinelli Editore. Here’s what I learned about the book from various Italian websites, Englished by my trusty computer. “In order to from birth celebrate the one hundred years of the ‘father of noir’ the Cornell Woolrich, its biographer Francis M. Nevins has collected… fourteen storys escapes on reviews pulp.”

Of “New York Blues,” the final tale in the collection, which “exited posthumous in 1970,” I was told that it’s “a splendid compendium, a epitaffio that it encloses in little pages all the reasons of the fiction of Woolrich: stilistico virtuosismo, evocativa force, dominion of the solitudine, struggimento for impossible loves, madness, desperation and dead women, that is all the colors of the buio.” Woolrich evokes “the tension of a city noir for excellence but in whose comparisons a visceral and unconditioned love can be nourished, nearly it blinds to you from its lights and the migliaia of dowels of solitudini that of it make the greatest agglomerate than history that the humanity could conceive….”

Woolrich’s New York “is a blues warm alternated to a jazz isterico, is a place where however it wants courage to us, is for living that in order to kill, is a cigarette to the poison with which you play the life in one night whichever.”

So that’s what Woolrich was all about! I was wondering.

Flitting from the master of noir to his nearest rival, I recently stumbled across a factoid about David Goodis which seems not to have surfaced before. It’s long been believed that Warner Bros., to whom Goodis was under contract in the late 1940s, did nothing with the multiple screenplays he wrote and later adapted into his novel Of Missing Persons (1950).

It turns out however that they did. Those screenplays were the source of “False Identity,” an episode of WB’s 60-minute TV series Bourbon Street Beat, which was aired on ABC during the 1959-60 season and starred Andrew Duggan and Richard Long as a pair of New Orleans private eyes. Air date was May 23, 1960. William J. Hole, Jr. directed from a teleplay by “W. Hermanos,” the house name used by just about everybody who wrote under the counter for WB during the then ongoing writers’ strike. Featured in the cast were Lisa Gaye, Irene Hervey and Tol Avery. How much authentic Goodis material survived the trip through the Warner Bros. TV sausage factory? I’d guess not a whole lot.

Flitting from fiction to film, I’ve also recently discovered the existence of a previously unknown work by my old friend Joseph H. Lewis (1907-2000), who is best known of course as the director of noir classics like Gun Crazy. During the late Fifties and early Sixties when Joe directed 51 episodes of Four Star’s hit TV series The Rifleman over its five-year run, he also helmed a few segments of other Four Star shows like The Detectives, and also, as I learned a few weeks ago, an episode of the Dick Powell Theater (NBC, 1961-63), a 60-minute anthology series.

“The Hook” (March 6, 1962) is about an investigator for the California Attorney General’s Office (Robert Loggia) who comes to suspect that the rule of a powerful underworld boss (Ray Danton) is about to be challenged by a former mob kingpin (Ed Begley) just released from prison. Finding out about this film was easy. The hard part begins when I try to track down a copy.

Like everyone who went to school when I did, I had great gobs of poetry shoved down my throat in my English classes, but I never developed a fondness for it except for what I discovered on my own, like the hilarious verses of Ogden Nash. My first sale to Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine more than 35 years ago was a piece of criminous doggerel in the Nash manner, and every so often a poem has figured in one of my stories or novels — for example, the toad quotations from Shakespeare, Kipling and Karl Shapiro in “Toad Cop.”

But those facts plus my having lived a block from Howard Nemerov between about 1980 and his death hardly qualify me as an authority on poetry. So it was rather odd that several months ago I was offered a princely fee by the Poetry Foundation, which has an endowment in the megamillions, to write an essay for its website on the links between poetry and crime fiction. That piece, along with Ed Park’s excellent discussion of poetry in the novels of Harry Stephen Keeler, is now a few clicks away from anyone with a computer at www.poetryfoundation.org.

The final version of my brief essay discusses only Hammett, Chandler and Ross Macdonald. But that thing went through more drafts than one of the toads in “Toad Cop” has warts, and a slew of interesting interfaces between poetry and mystery fiction wound up on the electronic cutting-room floor. This is why I plan to turn the final item in several future columns into a sort of Poetry Corner.

For space reasons I’ll keep my first specimen short and light. Fatal Descent (1939) was the only collaboration between two of the giants of the golden age of detective fiction, John Rhode and Carter Dickson (John Dickson Carr). Its plot seems to have been devised by both men but the writing is all Carr, a fact for which anyone who’s read Rhode’s dry-as-dust prose will thank whatever gods there be.

Investigating the impossible murder of a publisher while alone in a descending elevator, Scotland Yard’s Inspector Hornbeam takes time out to read a newspaper account of a speech by one of the suspects entitled “A Peak in Darien.” The inspector is unversed (sorry, couldn’t resist) in poetic allusion. “What’s Darien?” he asks Dr. Horatio Glass. “I’m not sure,” that brilliant amateur sleuth replies. “It’s a place where you’re supposed to stand silent and look at the Pacific. Why are you interested in all that guff, anyway?”

To the poetryphiles who read this column I promise that my next specimens will be more respectful.

Mon 12 Feb 2024

THE SAINT MAGAZINE. July 1967. Editor: Hans Stefan Santesson. Overall rating: ***

FLEMING LEE “The Gadget Lovers.” Simon Templar. Complete novel (73 pages), adapted from a teleplay by John Kruse. Russian spies are being murdered by exploding equipment, and naturally enough the Western allies are suspected. The Saint is sent to stop the assassination of a Colonel Smolenko, who turns out to be a woman. It is her idea to play the part of his secretary, as he becomes the target. The trail leads to Switzerland and to a monastery taken over by the Chinese. The handicaps of TV restrictions, and the required flashy beginning, are very well overcome. If the idea of a beautiful woman as a Russian officer can be accepted, the story becomes an interesting study of East meeting West. ****

MICHAEL INNES “Imperious Caesar.” John Appleby. First appeared in MacKill’s Mystery Magazine, April 1953. A malevolent professor commits suicide during a bloody Shakespearean production (4)

HELEN McCLOY “Through a Glass, Darkly.” Novelette. First appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, September 1948. Basil Wiling takes on the case of a woman who fears meeting her supernatural double. She has reason, for it is part of a plot to frighten her to death. Too many people take it too seriously, (2)

LEIGHLA WHIPPER “Death Comes of Chuchu Valente.” Miss Bennett [a recurring character], professional assassin, is hired to kill a Mexican bullfight announcer. Ridiculous. (1)

EDWARD D. HOCH “The Oblong Room.” Captain Leopold. An LSD religious experience leads to murder in a dormitory room. (3)

CORNELL WOOLRICH “Screen Test.” Jimmy Galbraith. First appeared in Dime Detective, November 1934, as “Preview of Death.”. A request for police protection fails as the heroine’s dress goes up in flames on the [movie] set, but the detective solves the case by watching the film rushes. A good story. (3)

— June 1968.

Tue 26 Dec 2023

REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2023. Issue #64. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: The White Elephant Mystery by Ellery Queen, Jr.

If you like detective fiction in any or all of its permutations then you can’t go wrong with Old-Time Detection. The new mingles with the old (which means, in most cases, the classic), leaving plenty for the reader to feast on.

Among the delectations: an interview with a science fiction/fantasy/detective story author; plenty of well-researched background on the creator of the world’s most famous criminal lawyer; the latest (at the time) paperback reprints from the seventies; a review of a collection of stories by the master of noir; a long-lost Dr. Poggioli story and a witty and amusing self-assessment by its author; a view of the “master conjurer” of fair play detection and a look at how he lived; news about the creator of Poirot and Marple and how the current generation is handling (and, in too many cases, mishandling) her works; a glance at how today’s publishers seem to be on some sort of nostalgia kick, which is good news for detec-fic aficionados; words about the undisputed “king of the classical whodunit”; and the editor’s appraisal of a kids’ novel that even adults can enjoy.

In it you will find:

(1) A 1976 interview with Isaac Asimov in EQMM: “I was the comic relief …”

(2) Francis M. Nevins gives us the first part of a multipart essay (2010) about Erle Stanley Gardner; however: “Those wishing to read about Gardner’s Perry Mason character must wait for Part Two.”

(3) Charles Shibuk continues his summary (1973) of the “paperback revolution” in detective/mystery publishing that was occurring half a century ago, focusing on Margery Allingham, Agatha Christie, Amanda Cross, Carter Dickson (otherwise JDC), Erle Stanley Gardner, Frank Gruber, Ngaio Marsh, Bill Pronzini, Rex Stout, Julian Symons, and Charles Williams.

(4) This is followed by Shibuk’s review (1975) of Nightwebs (1971), a collection of Cornell Woolrich’s “mainly unfamiliar works,” edited by Francis M. Nevins, Jr.: “Some of these stories are of extremely high quality, but alas, there is also much dross.”

(5) The issue’s centerpiece story is T. S. Stribling’s “The Mystery of the Paper Wad” (EQMM, 1946), which hasn’t been seen generally since first publication, followed by Stribling’s own “The Autobiography of an Ingenious Author” (1932): “The criminologist smiled at the illusion held by every man that with him all things, crimes and virtues, are possible.”

(6) In “The Full Mandrake” (2023), Rupert Holmes offers us “an appreciation of John Dickson Carr”: “If the classic fair play detective story is the magic act of literature, then John Dickson Carr is forever its master conjurer . . .”

(7) Douglas G. Greene’s assessment (1995) of JDC’s A Graveyard To Let (1949) (“. . . still, the swimming-pool gimmick is beautifully handled”), as well as Carr’s lifestyle as a New Yorker: “While he wrote in his attic study, Carr smoked continuously and tossed the cigarette butts on uncarpeted parts of the floor . . .”

(8) Dr. John Curran’s “Christie Corner” (2023) looks at what’s happening to AC’s heritage and finds all is not well, warning us about one project: “AVOID IT AT ALL COSTS.”

(9) Michael Dirda’s survey of the current scene, “Classical Mysteries Are Having a Moment” (2023): “. . . for devotees of old-time detection, recent publishing does seem surprisingly retrospective, even nostalgic.”

(10) Jon L. Breen’s article “Edward D. Hoch: King of the Classical Whodunit” (2008): “He practiced the increasingly lost art of the classical detective short story better than all but a handful of writers in the history of the genre.”

(11) There’s a mini-review of The White Elephant Mystery (1950) by Arthur Vidro: “It’s well-plotted and well-written . . .”

(12) As usual there’s a puzzle (and it’s a dilly).

(13) The issue ends with the sad news of Marvin Lachman’s passing: “Without Marv, we [at OTD] would have lacked the participation of leading professionals.”

____

Subscription information:

Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00. – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. – Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net