Search Results for 'Ellery Queen'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sun 27 Feb 2022

ELLERY QUEEN – The Four of Hearts. Stokes, hardcover, 1938. Pocket Books #245, paperback, 1943. Reprinted many times, including as one of the three novels in the omnibus volume The Hollywood Murders (J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1951).

The producer, not quite as eccentric as previously pictured (*) puts Ellery to work on a screenplay of the life stories of a famous actress and as equally famous actor. When they decide to patch up their feud which kept them apart for thirty years and finally marry, they are poisoned during their honeymoon flight. Ellery tried to keep the son and daughter apart but fails. The murderer plunges to his death as he tries to stop their wedding too.

An interesting interpretation of Hollywood types, and not only includes the two wild Hollywood weddings, but the double funeral is also extravagantly Hollywood. Ellery falls in love with Paula Paris, a columnist who will not leave her home, but who is able to provide him with clues to solve the case.

Good detection, a nicely complicated plot [with lots of detection and, even more, fun to read] – one of EQ’s best.

Rating: *****

–Nov-Dec 1967

(*) I assume but am not sure that this refers to the same producer Ellery worked for in The Devil to Pay, the previous “Hollywood†mystery and reviewed here.

Sun 13 Feb 2022

ELLERY QUEEN – The Devil to Pay. Stokes, hardcover, 1938. Pocket #270, paperback, 1944. Reprinted many times, including as one of the three novels in the omnibus volume The Hollywood Murders (J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1951). Also note: The Perfect Crime (Grosset & Dunlap, hardcover, 1942) was a novelization of the film Ellery Queen and the Perfect Crime (Columbia, 1941), which in turn was loosely based on this novel.

Ellery, as Hilary “Scoop†King, the wildest type of parody of a newspaperman, solves the murder of a crooked financialist, Solly Spaeth. After disastrous floods in the Midwest, Ohippi hydroelectric project collapsed, leaving all other stockholders ruined, including Spaeth’s partner. There is also the matter of the correct will, so there are plenty of motives.

A smooth, easy flow of words, a well-coordinated plot, and as “unlikely†but fairly obvious choice of murderer makes for enjoyable reading. However, there is nothing much to remember it by – I presumably have read it before, but nothing came back this time. Also included are Ellery’s experiences in trying to see an eccentric Hollywood producer.

Rating: ****

–November 1967

Fri 10 Dec 2021

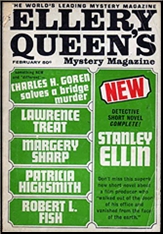

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE – February 1967. Overall rating: 3½ stars.

STANLEY ELLIN “The Twelfth Statue.†Short novel. A movie producer noted for his quickie productions and his weakness for young girls disappears from his closed-off Italian movie set. The location of his body seems to be obvious halfway through, but Ellin still has some twists left, in addition to masterful background. (5)

JANE SPEED “Fair’s Fair.†A child’s view of murder, that of a man who killed a cat. (4)

CHARLES B. CHILD “A Quality of Mercy. Reprinted from Collier’s, 11 March 1950. Inspector Chafik solves the murder of a blackmailer, but destroys the incriminating etter. Excellent background an characterization. (4)

ROBERT L. FISH “The Adventure of the Perforated Ulster.†Schlock Homes breaks up a plot by a trading stamp company to destroy confidence in British clubs. Hilarious. (5)

JUDITH O’NEILL “The Identification.†First story. Woman betrays rebel organizer. Awkward beginning. (2)

R. BRETNOR “Specimen of the Week.†Anthropological species turns on guardian.. (1)

S. K. SNEDEGAR “Charles H. Goren Solves a Bridge Murder.†Too bad I don’t know anything about bridge, but story was poor anyway. (0)

VINCENT McCONNOR “The Man Who Collected Obits.†Man who works in a newspaper morgue discovers weird coincidence in the daily obituaries. (3)

PATRICIA HIGHSMITH “Camera Fiend.” Reprinted from Cosmopolitan, September 1960, as “Camera Finish.†A not-so-bright murderer allows his picture to be taken with his victim. (3)

ARTHUR PORGES “The Scientist and the Multiple Murder.†Eight men are electrocuted in s rooftop pool. Seems contrived. (3)

MARGERY SHARP “Driving Home.†Reprinted from Good Housekeeping, August 1956. Man needs wife’s alibi and thus saves their marriage. Too much soppy writing. (2)

LAWRENCE TREAT “F As in Frame-Up.†A spendthrift husband is framed for murder involving theft of necklace. Lieutenant Decker’s hunch plays off. (4)

-November 1967

Mon 26 Jul 2021

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE. January 1967. Overall rating: 3½ stars.

HUGH PENTECOST “Volcano in the Mind.†Short novel. Dr. John Smith. First appeared in The American Magazine, December 1945, as “Volcano.â€

Dr. John Smith, an unobtrusive psychiatrist-detective, stops a clever murderer who is trying to drive a man to kill his wife, thus disposing of them both. Smith is very perceptive in his quiet way, but the story may be just a little dry. ****½

Bibliographic Update: Dr. John Smith appeared in three novellas in The American Magazine (collected in Memory of Murder, Ziff-Davis, 1947), one short story in EQMM, and two novels.

JULIAN SYMONS “The Santa Claus Club.†Francis Quarles. 1st US publication. Previously published in Suspense, UK, December 1960. A threatening letter typed on one of only 300 possible machines; a club where all dress up like Santa. The grand ’tec tradition? (2)

KENNETH MOORE “Protection.†An outsider wants some of the Orleans Street District action but needs protection. (3)

TALMAGE POWELL “Last Run of the Night.†A bus-driver is a killer. Obvious. (2)

HAROLD R. DANIELS “Deception Day.†A man commits a perfect murder in killing his shrewish wife. It’s too bad that justice, or conscience, had to win out. (4)

MICHAEL HARRISON “The Mystery of the Gilded Cheval-Glass.†A “hitherto unpublished†story of C. Auguste Dupin, who saves an artist from arrest by deciphering a dying ma’s last words. Let’s leave it for Poe enthusiasts. (2)

ROBERT McNEAR “The Salad Maker.†Mystery of the Absurd. That’s the right word. (1)

JAMES HOLDING “The New Zealand Bird Mystery.†The two authors of the Leroy King stories use a small scrap of writing for their deductions in solving a shipboard murder. (3)

BERNARD J. CURRAN “The Mysterious Mr Zora.†First story. Would 94,600 people not notice an extra 10¢ charge on their checking account? (1)

ELLERY QUEEN “Last Man to Die.†Reprinted from This Week, November 3 1963. Also published in the June 2004 issue of EQMM. QBI: Intelligence Department. A butlers’ club forms a tontine, the outcome of which EQ must decide. Not difficult. (3)

MICHAEL GILBERT “A Gathering of Eagles.†Previously published in Argosy (UK) January 1966, as “Heilige Nacht.†Calder and Behrens are called to Bonn to complete a cold-war breakthrough in Intelligence. Fast-moving and exciting. (4)

CHARLOTTE ARMSTRONG “The Cool Ones.†A grandmother’s quick thinking gives her grandson the clue to the location of her kidnappers. (3)

–September 1967

Sun 24 Jan 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

ELLERY QUEEN – The Fourth Side of the Triangle. Random House, hardcover, 1965. Paperback reprints include: Pocket, 1967; Ballantine, 1975, 1979. Actually written by Avram Davidson, from detailed story outline by Fred Dannay. TV pilot: 23 March 1975, as Ellery Queen: Too Many Suspects (screenwriters: Richard Levinson & William Link; Jim Hutton as EQ & David Wayne as Inspector Queen).

An earlier report on this later stage EQ novel was posted here as part of my series of Diary Reviews written over fifty years ago. Since a copy of the book came back into my hands soon after the earlier review went online, I thought coincidences like that should rewarded, and a re-read really really ought to take place. And so I did.

It’s a strange hybrid of a book in a couple of ways. First of all, although his name is on the title page, Ellery Queen didn’t really write it. As the bibliographic info up above so states, SF writer Avram Davidson did, following an outline furnished by Fred Dannay, who probably polished it afterward as well.

To me, the collaboration worked well. A second reading over this past weekend showed that either (A) I couldn’t tell that EQ himself didn’t write it, or maybe (B) it’s been so long since I’ve read an EQ novel that I couldn’t recognize a book written by EQ if my reputation as a devout reader of EQ in my youth depended on it.

The other double-headed nature of the book is that it was written in the midst of the Swinging Sixties, and the authors’ sensibilities suggested strongly that a book written in the 60s ought to reflect that, but also with the realization that maybe EQ readers in the 60s really wanted to read an EQ mystery of the 30s as well, complete with a wacky puzzle to be solved.

Which is exactly what this book provides. A leading character, a famous female dress-designer is known for her many companions in bed, lovers who come, however, serially, strictly one at a time. She has seen no reason to get married to any of them, an idea that was certainly around in the 30s but it would have been highly unlikely in an EQ novel.

The triangle of the title consists of (1) the aforementioned fashion designer, (2) her latest lover, (3) the man’s wife, and (4) the man’s son, who upon learning the liaison between father and mistress, decides to become the lady’s lover himself. Well, given the four sides as just described, it is not surprising that one of the them is killed, and each of the other three is put on trial for that person’s death, serially, one at a time.

It is obvious, I think, that this is a situation that would never come up in the real world, but in the world of Ellery Queen? Yes. Along with several twists along the way, a couple of mammoth coincidences and a wicked puzzle to be solved. Is Ellery Queen as an armchair detective (two broken legs) up to solving it? Read this one and see.

PostScript: I gave this one 3½ stars out of five the first time I read it. That’s an assessment that’s a little high this time around, but all in all, it’s close enough.

Tue 19 Jan 2021

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE, December 1966. Overall rating: 3 stars.

JACOB HAY “The Opposite Number.†The “inside†story of the spy business. (3)

AGATHA CHRISTIE “Hercule Poirot and the Sixth Chair.†Original title: “Yellow Iris.†Poirot stops a murder from occurring at a dinner party. (3)

WILLIAM BRITTAIN “The Boy Who Read Agatha Christie.†Schoolboy foils plan of college students. Enjoyable but trivial. (3)

ARTHUR PORGES “Private Beachhead.†Gimmick with radios too uncertain for story basis. (2)

YOUNGMAN CARTER “Seeds of Time.†SF story about visitor through time. Nothing unusual. (3)

CORNELL WOOLRICH “All It Takes Is Brains.†Novelette. Original title “Crime of St. Catherine Street.†Man on a bet enters Montreal with 75¢ and leaves with $1500, being wanted for murder in the meantime. Exciting in pulp style. (4)

CHRISTOPHER ANVIL “The Problem Solver and the Defector.†Verner finds secret plans. (3)

GEORGE EMMETT “Pushkin Pays.†Attempt to dispose of body in ocean fails, thanks to appearance of Russian submarine. (1)

HELEN NIELSEN “The Chicken Feed Mine.†Three ex-servicemen kill a desert rat for his “savings.†(3)

JOHN T. SLADEK “Capital C on Planet Amp.†SF, but in far-out camp style. Garbage. (0)

L. E. BEHNEY “The Long Hot Day.†Tale from home. Husband kills stranger his wife falsely accuses. (3)

JOHN DICKSON CARR “To Wake the Dead.†Original title “Blind Man’s Hood.†An adequate locked room mystery, but supernatural tone of story is forced. (2)

RUFUS KING “Anatomy of a Crime.†hort novel. Stuff Drscoll solves a murder made to appear a textbook suicide. Actually an inverted detective story as the reader follows the battle of wits between murderer and investigator with fascination. (4)

– August 1967

Sun 10 Jan 2021

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[12] Comments

ELLERY QUEEN – The Fourth Side of the Triangle. Random House, hardcover, 1965. Paperback reprints include: Pocket, 1967; Ballantine, 1975, 1979. Actually written by Avram Davidson, from detailed story outline by Fred Dannay. TV pilot: 23 March 1975, as Ellery Queen: Too Many Suspects (screenwriters: Richard Levinson & William Link; Jim Hutton as EQ & David Wayne as Inspector Queen).

Ellery, confined to bed with two broken legs, is involved with a strange love triangle consisting of Ashton and Lutetia McKell, their son Dane, and Ashton’s “mistress,†Sheila Gray. Upon learning his father’s secret, Dane tries to interfere and becomes Sheila’s lover himself.

When Sheila is murdered, the police arrest each member of the family in turn. After two dramatically ending trials, Dane’s parent are cleared, but a blackmailer implicates Dane, and he also is accused. Ellery’s deductions point to Ramon, the chauffeur, but he is only the blackmailer. It is Inspector Queen who discovers the final clue proving [the killer’s] guilt, one of his few triumphs over his son.

Maybe Perry Mason can do it once in each of his stories, but [two trials are] a bit far-fetched. The second in particular is concluded with a million-in-one accident providing a surprise witness, hardly believable.

The plot is rather clumsily handled through pages 80-83. Dane supposedly tells everything except his (first) attack, but the lack of reaction from his listeners makes it unclear if everything was told. But yet he must have disclosed both his father’s secret and his involvement, for both are implied later.

In fact, they confront his father with the story a few pages later, yet again he also has a surprising lack of reaction, even though the complete story has not come out at the trial. Confusing indeed, though not vitally affecting the mystery, the solution to which can at least be partially guessed.

Entertaining, but not completely satisfying.

Rating: 3½ stars.

– August 1967

Fri 6 Nov 2020

ELLERY QUEEN’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE, November 1966. Overall Rating: 2½ stars.

MICHAEL INNES “The End of the End.†Short novel. Sir John Appleby solves a murder committed in a snowbound English castle. Method of murder quite contrived to make it appear suicide. (3)

Comment: According to the cover, this was the first publication of this story. Based on my short description of it, it’s one of my favorite sub-genre of traditional Golden Age stories, even though published way later, in 1966.

EDWARD D HOCH “The Spy Who Walked Through Walls.†Rand of Concealed Communications. Mystery of disappearing reports has a very obvious solution. (2)

Comment: While always solid tales, Hoch’s Rand stories have never seemed as memorable to me as those with either Dr. Sam Hawthorne or Nick Velvet.

FRANK SISK “The Face Is Familiar.†Crooked con becmes involved in bank robbery by his cousin. (3)

JONATHAN CRAIG “Top Man.†A gangland story based on an eventually obvious pun. (2)

HENRY SLESAR “The Cop Who Liked Flowers.†A detective story with heart. (5)

Comment: The highest ranked story of this issue. Apparently a sentimental story that caught my fancy.

MIRIAM ALLEN deFORD “At the Eleventh Hour.†Another execution story: no surprises. (1)

PAMELA JAYNE KING “Nightmare.†Clever short-short [2 pages] by junior high stoudent, about a girl in trouble. (4)

Comment: This was this issue’s First Story, a standard feature of the magazine. up through and including today. While I enjoyed this one, the young author never published another work of crime fiction.

PHYLLIS BENTLEY “Miss Phipps and the Invisible Murderer.†Miss Phipps solves a church killing in the last four paragraphs [of a 13 page story]. (1)

Comment: Miss Phipps was a writer of detective novels who kept stumbling onto mysteries to solve. Her earliest appearance was in 1937, but none of her many others appeared until 1954. Several were collected in Chain of Witnesses: The Cases of Miss Phipps (Crippen & Landru, 2014), but I do not know if this is one of them.

J. F. PEIRCE “The Pale Face of the Rider.†German artists painting save daughter. Weird. (2)

GEORGES SIMENON “Inspector Maigret Deduces.†First US publication. Maigret solves train murder from studying character. No real clues. (2)

Comment: This was, of course, Maigret’s usual way of solving crimes.

JAMES CROSS “The Hkzmp gav Bzmp Case.†The spy story is demolished by this inane nonsense. Title is code for “Spank the Yank.†(3)

VINCENT McCONNOR “Pauline or Denise.†Murder of his two sisters leaves playboy trapped in asylum. Distinctly French. (4)

HOLLY ROTH “The Game’s the Thing.†An interesting anticipation of Dr. Berne, but story may be overshadowed. (3)

Comment: Dr. Berne was the author of Games People Play: The Basic Handbook of Transactional Analysis (1964). This was Holly Roth’s last published story; she died in 1964.

LAWRENCE TREAT “M As in Mugged.†Lieutenant Decker’s 60th birthday. A comparison of present and past police methods, with experience the key factor. (1)

Mon 4 Mar 2019

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

ELLERY QUEEN – The Dutch Shoe Mystery. Ellery Queen #4. Stokes, hardcover, 1931. Paperback reprints include Pocket #202; 1st printing, December 1942.

Subtitled “A Problem in Deduction” (*) and that is exactly correct. The wealthy benefactress of a New York City hospital is murdered just before undergoing an emergency operation on the same building, and the only clue is a pair of shoes with a mended shoelace.

No one should read an Ellery Queen novel of this vintage for a study of the characters involved, but for the most part the prose is clean and uncluttered. The only exception being a tendency toward flowery language at the beginning of every section. The rest of the story is punctuated only occasionally by the presence of yet another footnote. The lack of action is made up for by a plot that, when unraveled, has no flaws, so far as I can see.

(*) There is a ‘Challenge to the Reader’ on page 241 of the Pocket edition, and as usual, I flubbed it up. And yet, if I’d followed through on the thought that occurred to me on page 32, I’d have nailed the culprit in no tie flat. I kid you not.

–Reprinted in slightly revised form from Mystery*File #16, October 1989.

Fri 3 Aug 2018

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Suppose all the readers of this column were gathered together in one room. At the front, standing before the lectern or podium or whatever the hell you call it, I pose a question: Any of you know something about Tom Everitt? Almost everyone in the room would probably answer: “Tom Whoveritt?†Perhaps one or two who had read my book THE ART OF DETECTION and were blessed with a photographic memory might say: “Wasn’t he the guy who provided the plots for Manny Lee to turn into Ellery Queen radio scripts after Fred Dannay dropped out and before Anthony Boucher came aboard?â€

Indeed he was. But aside from that fact, and the titles of more than thirty EQ scripts that were based on Everitt plot synopses, virtually nothing is known of him. While working on THE ART OF DETECTION I had ransacked the Web looking for a little more information about this mystery man but with no luck. Then out of the blue not long ago I received an email from a total stranger who, in the course of researching something else entirely, had unearthed more information about Everitt than I could have used even had I known of it in time to put it in the book. But there’s no reason I can’t summarize it here. Thank you, Jonathan Guss, for making this month’s column possible.

John Thompson Everitt, whom I’ll call JT just to make things simple, was born in Yonkers, New York on December 11, 1908. His ancestors had arrived in Massachusetts by 1643 and had settled in the New York City area near Jamaica by 1650. JT’s father, Charles Percy Everitt (1873-1951), was a well-known rare book dealer, and Charles’ brother Samuel Alexander Everitt (1871-1953) was a partner in the Doubleday publishing house until his retirement in 1930. JT’s older brother Charles Raymond Everitt (1901-1947) also went into the publishing business, working at Harcourt Brace and later, until his early death, at Little Brown, the publisher of a volume of memoirs by his and JT’s father (THE ADVENTURES OF A TREASURE HUNTER: A RARE BOOKMAN IN SEARCH OF AMERICAN HISTORY, 1951).

In 1930 JT graduated from Yale, where he was known as a soccer player. A year later he was hired by the CBS radio network to write for its March of Time program. By 1940 he had moved into the advertising side of radio at the Young & Rubicam agency where, among many other jobs, he was tasked with handling a prospectus from the NBC radio network on The Green Hornet, for which NBC was seeking a sponsor. Apparently he was still working at that agency when he became involved with the Ellery Queen series.

Since its debut in June of 1939, every one of the scripts for the series had been written by Manfred B. Lee based on plot synopses prepared by his cousin and EQ collaborator Fred Dannay. (More precisely, every one except “The Dauphin’s Doll,†first broadcast around Christmastime 1943 and written by Manny alone.) Early in 1944 Fred’s wife was diagnosed with cancer. The burdens of taking care of two young children, plus editing a large annual anthology of short mystery fiction and running Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (EQMM), which had been launched in the fall of 1941, soon made it impossible for Fred to continue coming up with a plot a week for the radio series.

He was several synopses ahead when he dropped out, and Manny squirreled these away for use in emergencies, relying most of the time on recycling earlier scripts under new titles and condensing 60-minute scripts from the show’s first season (1939-40) into its current half-hour format. But these ploys couldn’t go on indefinitely. Somebody had to be found to take over Fred’s function.

How TJ came into the picture remains unknown. Possibly it was through his older brother Charles, who was working at Little Brown, publisher of the Queen novels and anthologies since 1942. Perhaps it was due to the connections Fred and Manny had retained with the advertising and publicity businesses where they’d gotten their start. Whether he was the first man brought in to assume Fred’s function as plot provider remains unclear.

We don’t know exactly how many Dannay synopses Manny had in reserve, but several of the episodes dating from late 1944 strike me as too outrageous to have stemmed from Fred. Take, for example, “Cleopatra’s Snake†(October 12 & 14, 1944). As backstage observer of a live production of Antony and Cleopatra for experimental TV, Ellery becomes a key witness when the genuine poisonous snake being used in the death scene (yeah, right) bites to death the actress playing Cleopatra.

Now let’s consider “The Glass Sword†(November 30 & December 2, 1944), in which Ellery tackles the case of the circus sword swallower who died when the sword in his stomach broke while the lights were out. Was it Everitt who cranked out the synopses that Manny turned into these scripts? Was it another Dannay substitute? Or, wacko though they are, could they have originated with Fred after all? For more information, keep reading.

The earliest EQ script that we know came from a synopsis by Everitt was “The Diamond Fence†(January 24, 1945), which involves the murder of a middleman for stolen gems and the disappearance of five diamond rings from the scene of the crime under impossible circumstances. A substantial excerpt from this episode survives on audio as a “sneak preview†from the Armed Forces Radio Service.

From that point at least through the end of March, every script Manny wrote was based on Everitt material. It was during these early months of the last full year of World War II that Manny enlisted Anthony Boucher (1911-1968) to take over Everitt’s function. It was an ideal choice. Boucher had already published seven novels in the Queen vein and had had short stories published in EQMM. Also, as we know from comments in various of his mystery reviews for the San Francisco Chronicle, he was an enthusiastic fan of the radio series.

Since Tony lived in Berkeley, California and Manny on the east coast, collaboration on EQ radio scripts required vast correspondence between the two. This correspondence, archived at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, documents their work together in microscopic detail. The only aspect of it that concerns us here is Manny’s continual snarky remarks about Everitt, of which I’ll quote a few.

On May 3, 1945, about six weeks before the broadcast of the first Boucher-Lee collaboration, Manny tells Tony that he’s “washed up†with Everitt, who “will do four more for us, and then he’s through. This by mutual agreement.†On the 17th of the same month, he says: “We want to avoid some of the weaknesses resulting from our present man’s so-called efforts….†And on the 24th he lets Tony know how he really feels about Everitt: “….At the end of our association with our ‘man,’ as I like to call him—hating his smug, treacherous guts as I do!—we’re finding more trouble…and sloppier submissions on his part even than usual….â€

On January 24, 1946, he describes one of the Everitt synopses he had to deal with as “a bad outline which I bought only because I was desperate …and bought and paid for it with the mental reservation that I’d probably have to do a thorough re-working job on it. I was a noble prophet.â€

But, simply because the EQ radio formula was so complex and demanding and Boucher with all his other commitments couldn’t conjure up a new plot synopsis on a weekly basis, Manny was forced to make further commitments to Everitt. “This was a desperation move,†he tells Boucher on October 30, 1946, “as his stuff always gives me headaches, but good….I had to do something in self-protection. I heartily wish now I hadn’t made that commitment…. But it can’t be undone and I can only hope that he doesn’t come through, so that I can order more from you.â€

Almost a year later Manny is still reluctantly dealing with Everitt now and then and, in a letter to Fred Dannay dated November 4, 1947, griping about it just as loudly. Discussing the possibility of repeating some of the scripts based on Everitt synopses, he describes Everitt as “such a son-of-a-bitch that, even though our rights to repeat the material without payment are clear, he would raise a considerable stink in the business if we didn’t pay him an extra fee….[F]or the most part he got tremendously overpaid in the original payment—the bulk of the creative work was done by me, out of sheer necessity.â€

If Manny were to offer a token fee of perhaps $50 per episode recycled, Everitt “would start haggling and chiseling and his tongue would wag plenty in the business….†What business Manny is referring to becomes clear later in the same letter. “[Y]ou don’t know…what that bastard has been saying and is still saying in the advertising business about his ‘part’ in the Queen show. There is no protection against his kind of conscienceless and unscrupulously shrewd self-propaganda….â€

As his correspondence with both Fred and Boucher demonstrates, at least during the radio years Manny was a Type A personality with a genius for getting hot under the collar, and the insane pressure of putting out a program every week probably shortened his life.

Whether he was being too harsh on JT is hard to judge. One of the few living persons to have seen any of the Everitt material Manny turned into scripts is Ted Hertel, who helped choose the scripts included in THE ADVENTURE OF THE MURDERED MOTHS (2005). In connection with that project he was erroneously sent the synopses for “The Right End†and “The Glass Sword,†both with Everitt’s name on them.

To judge by Ted’s comments, what Everitt gave Manny to work with was just as bad as Manny said it was. In an email to me he described the synopses as “so poorly written, so amateurish, that they could not possibly have been the work of Manny in any form.†(The scripts Manny based on these synopses were broadcast respectively on November 16 and 30, 1944.)

Only one episode Manny based on an Everitt synopsis is available on audio. In “Number 31″ (September 7, 1947) Ellery tries to crack the secret of international mystery man George Arcaris’s success at smuggling diamonds into the Port of New York and to comfort a wonderfully dignified black woman by solving the murder of her son, the servant for a wealthy man-about-town. The cases seem unconnected until Ellery discovers the number 31 popping up in both.

It’s an excellent episode, but how much credit should go to Everitt remains a mystery since no one in the last 70 years has seen his synopsis. I wouldn’t be surprised if the black woman was entirely the creation of the staunchly liberal Manny Lee.

To the best of my knowledge the only Everitt radio work besides his EQ plots was a single script for The Shadow. In “The Creature That Kills†(January 6, 1946) Lamont Cranston, alias The Shadow, investigates the theft of priceless papers from the 20th-floor laboratory of a brilliant young scientist under impossible circumstances.

It turns out that the thief, a master criminal with a Sydney Greenstreet voice, had an accomplice in the form of a trained 27-foot python which slid down the side of the building from the window directly above the scientist’s lab, got hold of the papers, then slid back up the wall to its master. What a snake! Do I detect here the same kind of wackiosity that pervades the EQ scripts about Cleopatra and the glass sword?

In 1947 Everitt returned to radio full-time as Eastern program manager for the ABC network. We don’t know if he wrote any more for the medium, but Jonathan Guss mentions one script he contributed to the golden age of live TV drama, “Revenge by Proxy†(Colgate Theatre, May 14, 1950). The cast included Nancy Coleman, Phil Arthur, Bernard Kates and Victor Sutherland. As chance would have it, the following week’s drama, “Change of Murder,†was based on a short story by Cornell Woolrich.

Everitt died on November 2, 1954, at age 45. Today he seems to be totally forgotten, perhaps deservedly so. The most that can be claimed for him is that he figures as a footnote in the Ellery Queen story. But at least now that footnote has been written.