Search Results for 'Nicholas Blake'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Thu 14 Oct 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

On Sunday, September 12, at age 80, Claude Chabrol died. He was one of the most creative French film directors, and one of the most deeply committed to the crime-suspense genre, and the only one I ever met.

It was in the summer of 1986, at an international festival on Italy’s Adriatic coast where he and I and countless others were guests. We were introduced by another mystery writer, the late Stuart Kaminsky, and over the next several days we were on some tours together — including one to the castle of Cagliostro — and had a number of conversations.

I can’t claim to have seen all or even most of the dozens of films Chabrol directed in his career of more than half a century behind the cameras, not even all the crime-suspense-noir pictures with which his filmography is studded.

But among those I knew well were 1969’s Que la bête meure (The Beast Must Die) and, from 1971, La décade prodigieuse (Ten Days’ Wonder), the former very freely based on a classic Nicholas Blake novel and the latter on a classic by Ellery Queen.

His then most recent film, which was premiered at the festival, was Inspecteur Lavardin. After seeing Lavardin, and connecting what I took to be dots between it and the other two, I saw all three as sharing a common theme: the meaning of being a father.

Remembering that Ten Days’ Wonder in both novel and film form climaxed with a death-of-God sequence, I ventured to suggest to him that all three films tell us: “There is no God the father, therefore we must be good fathers.†His reply: “Yes, yes, yes!â€

We talked about Cornell Woolrich, a few of whose stories he had adapted and directed for French TV, and after returning to the States I sent him, at his request, a few Woolrich tales that might be adapted into Chabrol features.

Nothing came of this, but among the many films he made in the quarter century after our meeting was Merci pour le chocolat (2000), based on Charlotte Armstrong’s The Chocolate Cobweb, which is also centrally about fatherhood. Among the other world-class crime novelists whose work he translated to film are Stanley Ellin, Patricia Highsmith and Georges Simenon. Adieu, cher maître.

In my student years I read just about every one of Frances and Richard Lockridge’s Mr. & Mrs. North mysteries, but I hadn’t revisited any of them in decades. Recently I reread The Norths Meet Murder (1940), first in the long-running series, and found it as charming and enjoyable as I had long ago.

It’s also a lovely piece of evidence in support of Anthony Boucher’s contention that one of the valuable functions of mysteries is that they show later generations what life was like “back then.â€

The Norths Meet Murder takes place in late October and early November 1939. On September 1 Hitler had launched World War II, and in New York there’s an organized boycott against buying “Nazi goods,†which impacts at least one of the murder suspects.

The latest consumer novelty is the electric razor. Walking New York’s night streets, you see men working on the new subway line under floodlights. Those who read this novel back in 1940 probably took these verbal snapshots for granted, just as those of us who as kids watched the early TV private-eye series Man Against Crime took for granted the chases all over the New York landmarks of the early 1950s.

Now in the 21st century they strike me as treasures, and perhaps help explain why, given the choice between a vintage whodunit or a new one, or an episode of a vintage TV series or a new one, I tend to go for the gold in the old.

I recently attended a convention in suburban Baltimore but arrived before my hotel room was ready. Luckily there was a bookstore with comfortable chairs in the mall across the street, and I killed some time in the mystery section with “Arson Plus,†the first of Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op stories, originally published in Black Mask for October 1, 1923 and recently reprinted in Otto Penzler’s mammoth Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories.

For decades this was one of the rarest of Hammett tales, revived only by Fred Dannay (in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, August 1951, and in the Queen-edited paperback collection Woman in the Dark, 1951).

Today it’s in the Penzler anthology and a major hardcover Hammett collection (Crime Stories and Other Writings, Library of America 2001) and can also be downloaded from the Web in a few seconds.

The other day I felt an urge to compare the e-text with the EQMM and Library of America versions, and made a discovery that startled but didn’t really surprise me. The Web version I downloaded is identical with Fred’s except for a few changes in punctuation and italicization, but both are quite different from the Library of America text, which uses the version originally published in Black Mask.

Fred believed that every story ever written was too long and therefore tended to trim the tales he reprinted, even those by masters like Hammett. Some of the bits and pieces he cut were perhaps redundant, but he also axed part of the Continental Op’s explanation at the end of the story.

Reprinting “Arson Plus†in 1951, he must have felt a need to update some of the price references to reflect post-World War II inflation. At the very beginning of the original version, the Op offers a cigar to the Sacramento County sheriff, who estimates that it cost “fifteen cents straight.†The Op corrects him, giving the price as two for a quarter. Fred raised these figures to “three for a buck†and â€two bits each†respectively.

He also added a cool ten thousand dollars to the purchase price of a house that in the 1923 version sold for $4,500. Where a Hammett character disposes of $4,000 in Liberty bonds (sold by the government to finance World War I), Fred has him sell $15,000 worth of common or garden variety bonds.

Whenever Hammett refers to an automobile as a “machine,†Fred changes it to “car.†Where three men in a general store are “talking Hiram Johnson,†Fred has them merely “talking.†(Hiram Johnson, as we learn from a note in the Library of America volume, was governor of California between 1911 and 1917 and later served four terms as senator.)

He also unaccountably changes the name of a major character from Handerson to Henderson. A quick check of Fred’s versions of a few other Continental Op stories with the original texts yielded similar results and a clear conclusion: to read Hammett’s tales as they were meant to be read, you have to read them in the Library of America collection. This doesn’t help, of course, with the eight Op stories not collected in that volume, but it’s a start.

In every version of “Arson Plus†the plot is of course the same: a man insures his life for big bucks, assumes another identity, sets fire to the house he bought, and the woman named as beneficiary demands payment.

Did these people really think any insurance company would be fooled for a minute when there were no human remains in the ashes of the destroyed house? Didn’t Hammett with his experience as a PI realize that this plot was ridiculous? Was Fred ever bothered by its silliness?

My nonfiction collection Cornucopia of Crime, which I subtly plugged a few columns ago, is now officially available (Ramble House, 2010).

So too is Night Forms (Perfect Crime Books), a collection of 28 of the short stories I’ve written over the last four decades including my earliest (“Open Letter to Survivorsâ€), my latest (“The Skull of the Stuttering Gunfighterâ€), and a huge pile of tales that fall between that unmatched pair.

I’ve completely forgotten where the picture of me on the back cover came from, but whoever took it deserves some kind of award for improving on reality more than any other photographer in history.

Wed 6 Oct 2010

150 Favorite Golden Age British Detective Novels:

A Very Personal Selection, by Curt J. Evans

Qualifications are the writers had to publish their first true detective novel between 1920 and 1941 (the true Golden Age) and be British or close enough (Carr). So writers like, say, R. Austin Freeman, Michael Gilbert and S. S. Van Dine get excluded.

I wanted to get outside the box a bit and so I’m sure I made what will strike some as some odd choices. This is a personal list. If I were making a totally representative list John Dickson Carr’s The Three Coffins, Nicholas Blake’s The Beast Must Die, Michael Innes’ Lament for a Maker, Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case, Sayers’ Gaudy Night, etc., would all be there). And lists evolve over time. It’s highly likely, for example, that as I read more of Anthony Wynne and David Hume, for example, they would get more listings.

Also I excluded great novels like And Then There Were None, The Burning Court and Trial and Error, for example, because I felt like they didn’t fully fit the definition of true detective novels. In any list list I would make of great mysteries, they would be there.

If people conclude from this list that my five favorite Golden Age generation British detective novelists are Christie, Street, Mitchell, Carr and Bruce, that would be fair enough, though I must add that they were very prolific writers, so more listings shouldn’t be so surprising.

The 150 novels break down by decade as follows:

1920s 9 (6%)

1930s 87 (58%)

1940s 30 (20%)

1950s and beyond 24 (16%)

A pretty graphic indicator of my preference for the 1930s!

Also, of the 61 writers, I believe 40 are men and 21 women — I hope my count is right! — which challenges the conventional view today that most British detective novels of the Golden Age were produced by women. Of these, 31, or just over half, eventually became members of the Detection Club. I exclude a few of these luminaries, such as Ronald Knox and Victor Whitechurch (am I anti-clerical?!).

JOHN DICKSON CARR (8)

The Crooked Hinge (1938)

The Judas Window (1938) (as Carter Dickson)

The Reader Is Warned (1939) (as Carter Dickson)

The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940)

The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941)

The Gilded Man (1942) (as Carter Dickson)

She Died a Lady (1944) (as Carter Dickson)

He Who Whispers (1946)

â— It’s probably sacrilege not to have The Three Coffins on the list (especially when you have The Gilded Man!), but when I read Coffins I enjoyed it for the horror more than the locked room, which seemed overcomplicated too me (need to reread though).

AGATHA CHRISTIE (8)

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd 1926

Murder at the Vicarage 1930

The ABC Murders 1936

Death on the Nile 1937

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe 1940

Five Little Pigs 1942

A Murder Is Announced 1950

The Pale Horse 1961

â— Haven’t reread The ABC Murders recently; was somewhat disappointed with Murder on the Orient Express when rereading and thus excluded from the list. And Then There Were None regretfully excluded, because I wasn’t sure it really qualifies as a detective story (there’s not really a detective and the solution comes per accidens).

GLADYS MITCHELL (8)

Speedy Death (1929)

The Mystery of a Butcher’s Shop (1929)

The Saltmarsh Murders (1932)

Death at the Opera (1934)

The Devil at Saxon Wall (1935)

St. Peter’s Finger (1938)

The Rising of the Moon (1944)

Late, Late in the Evening (1976)

â— A true original, but not to everyone’s taste.

JOHN RHODE (MAJOR CECIL JOHN CHARLES STREET) (8)

The Davidson Case (1929)

Shot at Dawn (1934)

The Corpse in the Car (1935)

Death on the Board (1937)

The Bloody Tower (1938)

Death at the Helm (1941)

Murder, M.D. (1943) (as Miles Burton)

Vegetable Duck (1944)

â— The Golden Age master of murder means, underrated in my view.

LEO BRUCE (8)

Case for Three Detectives (1936)

Case with Ropes and Rings (1940)

Case for Sergeant Beef (1947)

Our Jubilee is Death (1959)

Furious Old Women (1960)

A Bone and a Hank of Hair (1961)

Nothing Like Blood (1962)

Death at Hallows End (1965)

â— In print but underappreciated, he carried on the Golden Age witty puzzle tradition in a tarnishing era for puzzle lovers.

J. J. CONNINGTON (5)

The Case With Nine Solutions (1929)

The Sweepstake Murders (1935)

The Castleford Conundrum (1932)

The Ha-Ha Case (1934)

In Whose Dim Shadow (1935)

â— An accomplished, knowledgeable puzzler.

E.C.R. LORAC (EDITH CAROLINE RIVETT) (5)

Death of An Author (1935)

Policemen in the Precinct (1949)

Murder of a Martinet (1951)

Murder in the Mill-Race (1952)

The Double Turn (1956) (as Carol Carnac)

â— Has taken a back seat to the Crime Queens, but was very prolific and often quite good (my favorites, as can be seen, are more from the 1950s, when she became a little less convention bound).

E. R. PUNSHON (5)

Genius in Murder (1932)

Crossword Mystery (1934)

Mystery of Mr. Jessop (1937)

Ten Star Clues (1941)

Diabolic Candelabra (1942)

â— Admired by Sayers, this longtime professional writer (he published novels for over half a century) is underservingly out of print.

MARGERY ALLINGHAM (4)

Death of a Ghost (1934)

The Case of the Late Pig (1937)

Dancers in Mourning (1937)

More Work for the Undertaker (1949)

â— Her imagination tends to overflow the banks of pure detection, but these are very good, genuine puzzles.

G. D. H. and MARGARET COLE (4)

Burglars in Bucks (1930)

The Brothers Sackville (1936)

Disgrace to the College (1937)

Counterpoint Murder (1940)

â— Clever tales by husband and wife academics not altogether justly classified as “Humdrums.”

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS (4)

The Sea Mystery (1928)

Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930)

The Hog’s Back Mystery (1933)

Mystery on Southampton Water (1934)

â— The “Alibi King,” he’s more paid lip service (particularly for genre milestone The Cask) than actually read today, but at his best he is is worth reading for puzzle fans.

NGAIO MARSH (4)

Artists in Crime (1938)

Seath in a White Tie (1938)

Surfeit of Lampreys (1940)

Opening Night (1951)

â— Art, society and theater all appealingly addressed by a very witty writer, with genuine detection included.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS (4)

Strong Poison (1930)

The Five Red Herrings (1931)

Have His Carcase (1932)

Murder Must Advertise (1933)

â— As can be guessed I prefer middle period Sayers — less facetious than earlier books, but also less self-important than later ones.

HENRY WADE (4)

The Dying Alderman (1930)

No Friendly Drop (1931)

Lonely Magdalen (1940)

A Dying Fall (1955)

â— Very underrated writer — some other good works (Mist on the Saltings, Heir Presumptive) were left out because they are more crime novels.

JOSEPHINE BELL (3)

Murder in Hospital (1937)

From Natural Causes (1939)

Death in Retirement (1956)

â— Far less known than the Crime Queens, but a worthy if inconsistent author.

NICHOLAS BLAKE (3)

A Question of Proof (1935)

Thou Shell of Death (1936)

Minute for Murder (1949)

â— His most important book in genre history is The Beast Must Die, but I prefer these as puzzles.

CHRISTIANNA BRAND (3)

Death in High Heels (1941)

Green for Danger (1945)

Tour de Force (1955)

â— One of the few who can match Christie in the capacity to surprise while playing fair.

JOANNA CANNAN (3)

They Rang Up the Police (1939)

Murder Included (1950)

And Be a Villain (1958)

â— Underrated mainstream novelist who dabbled in detection.

BELTON COBB (3)

The Poisoner’s Mistake (1936)

Quickly Dead (1937)

Like a Guilty Thing (1938)

â— Almost forgotten, but an enjoyable, humanist detective novelist (B. C. worked in the publishing industry and was the son of novelist Thomas Cobb, who also wrote mysteries)

JEFFERSON FARJEON (3)

Thirteen Guests (1938)

The Judge Sums Up (1942)

The Double Crime (1953)

â— A member of the famous and talented Farjeon family (both his father Benjamin and sister Eleanor were notable writers), he wrote mostly thrillers but produced some more genuine detection.

ELIZABETH FERRARS (3)

Give a Corpse a Bad Name (1940)

Neck in a Noose (1942)

Enough to Kill a Horse (1955)

â— Came in at the tail-end of the Golden Age, like Brand, though she was more prolific (and not as good). She started with an appealing Lord Peter Wimsey knock-off (Toby Dyke), but eventually helped found the more middle class and modern “country cottage” mystery (downsized from the country house).

CYRIL HARE (3)

When the Wind Blows (1949)

An English Murder (1951)

That Yew Trees Shade (1954)

â— Another one who came in near the end of the Golden Age proper, his best is considered to be Tragedy at Law (see P. D. James), but I like best the tales he produced in postwar years.

R. C. WOODTHORPE (3)

The Public School Murder (1932)

A Dagger in Fleet Street (1934)

The Shadow on the Downs (1935)

â— A surprisingly underrated writer, witty and clever in the the way people like English mystery writers to be (why has no one reprinted him?).

ROGER EAST (2)

The Bell Is Answered (1934)

Twenty-Five Sanitary Inspectors (1935)

â— Another mostly forgotten farceur of detection.

GEORGE GOODCHILD & BECHHOFER ROBERTS (2)

Tidings of Joy (1934)

We Shot an Arrow (1939)

â— Working together, these two authors (one, Goodchild, a prolific thriller writer) produced some fine detective novels (their best-known works are a pair based on real life trials).

GEORGETTE HEYER (2)

A Blunt Instrument (1938)

Detection Unlimited (1953)

â— Better known for her Regency romances (still read today), Heyer produced some admired exuberantly humorous (if a bit formulaic) detective novels (plotted by her husband).

ELSPETH HUXLEY (2)

Murder on Safari (1938)

Death of an Aryan (1939)

â— After a decent apprentice genre effort, this fine writer produced two fine detective novels, interestingly set in Africa, with an excellent series detective.

MICHAEL INNES (2)

The Daffodil Affair (1942)

What Happened at Hazelwood (1946)

â— So exuberantly imaginative, he is hard to contain within the banks of true detection, but these are close enough, I think, and I prefer them to his earlier, better-known works.

MILWARD KENNEDY (2)

Death in a Deck Chair (1930)

Corpse in Cold Storage ((1934)

â— A neglected mainstay of the Detection Club, hardly read today.

C. H. B. KITCHIN (2)

Death of My Aunt (1929)

Death of His Uncle (1939)

â— These are fairly well-known attempts at more literate detective fiction, by an accomplished serious novelist.

PHILIP MACDONALD (2)

Rynox (1930)

The Maze (1932)

â— A writer who often stepped into thriller territory (and produced some classics of that form), he produced with these two books closer efforts at true detection (indeed, the latter is a pure puzzle)

CLIFFORD WITTING (2)

Midsummer Murder (1937)

Measure for Murder (1941)

â— Clever efforts by an underappreciated author.

FRANCIS BEEDING

He Should Not Have Slipped! (1939)

â— About the closest I would say that this author (actually two men) came to full dress detection.

ANTHONY BERKELEY

Not to be Taken (1938)

â— A true detective novel and first-rate village poisoning tale by this important figure in the mystery genre, who often tweaked conventional detection.

DOROTHY BOWERS

The Bells of Old Bailey (1947)

â— Best of this literate lady’s detective novels, her last before her untimely death.

CHRISTOPHER BUSH

Cut-Throat (1932)

â— Prolific writer who is not my favorite, but I liked this one, with its clever alibi problem.

A. FIELDING

The Upfold Farm Mystery (1931)

â— Uneven, prolific detective novelist, but this one has much to please.

ROBERT GORE-BROWNE

Murder of an M.P.! (1928)

â— One of my favorite 1920s detective novels, by a mere dabbler in the field.

CECIL FREEMAN GREGG

Expert Evidence (1938)

â— Surprisingly cerebral effort by a “tough” British thriller writer.

ANTHONY GILBERT

Murder Comes Home (1950)

â— My favorite books by this author tend to be more suspense than true detection.

JAMES HILTON

Murder at School (1931)

â— Good foray into detection by well-regarded straight novelist.

RICHARD HULL

The Ghost It Was (1936)

â— About the closest I would say that this crime novelist came to detection.

DAVID HUME

Bullets Bite Deep (1932)

â— Though this series later devolved into beat ’em up thrillers, this first effort has genuine detection (and American gangsters). More reading of this author’s other series may yield additional results.

IANTHE JERROLD

Dead Man’s Quarry (1930)

â— One of the two detective novels by a forgotten member of the Detection Club, more a mainstream novelist (though forgotten in that capacity as well).

A. G. MACDONELL

Body Found Stabbed (1932) (as John Cameron)

â— Detective novel by writer better known for his satire.

PAUL MCGUIRE

Burial Service (1939)

â— Mostly forgotten Australian-born writer of detective fiction, mostly set in Britain. This tale, his finest, is not. It one of the most original of the period.

JAMES QUINCE

Casual Slaughters (1935)

â— A very good, virtually unknown village tale.

LAURENCE MEYNELL

On the Night of the 18th…. (1936)

â— More realistic detective novel for the place and period, in terms of its depiction of often unattractive human motivations, by a writer who veered more toward thrillers and crime novels.

A. A. MILNE

The Red House Mystery (1922)

â— A well-known classic, mocked by Chandler — but, hey, what a sourpuss he was, what?

EDEN PHILLPOTTS

The Captain’s Curio (1933)

â— Counted because his true detection started in the Golden Age. His best work, however, is found in crime novels (and straight novels)

E. BAKER QUINN

One Man’s Muddle (1937)

â— A strikingly hardboiled tale by a little-known author who was written of on this website fairly recently.

HARRIET RUTLAND

Knock, Murderer, Knock! (1939)

â— Mysterious individual who wrote three acidulous detective novels. This is the first, a classic spa tale.

CHRISTOPHER ST. JOHN SPRIGG

The Perfect Alibi (1934)

â— A fine farceur of detection, whose genre talent was purged when he became a humorless Stalinist ideologue (he was killed in action in Spain).

W. STANLEY SYKES

The Missing Moneylender (1931)

â— Controversial because of comments about Jews (as the title should suggest), yet extremely clever.

JOSEPHINE TEY

The Franchise Affair (1948)

â— Genuine detection, though veering into crime novel territory (and veering very well, thank you).

EDGAR WALLACE

The Clue of the Silver Key (1930)

â— One of the closest attempts at true detection by the famed thriller writer.

ETHEL LINA WHITE

She Faded Into Air (1941)

â— See Edgar Wallace. A classic vanishing case, with some of the author’s patented shuddery moments.

ANTHONY WYNNE

Murder of a Lady (1931)

â— Fine locked room novel by an author who tended to be too formulaic but could be good (can probably add one or two more as I read him).

Editorial Comment: Coming up soon (as soon as I can format it for posting) and covering some of the same ground as Curt’s, is a list of “100 Good Detective Novels,” by Mike Grost. The emphasis is also on detective fiction, so obviously some of the authors will be the same as those in Curt’s list, but Mike doesn’t restrict himself to British authors, and the time period is much wider, ranging from 1866 to 1988, and the actual overlap is very small.

Tue 5 Oct 2010

A LIST OF FAVOURITES

by Geoff Bradley

This is a list of books that appealed to me as I read them. I have simply gone on my fond memories of reading them, some many years ago, in a few cases when I was just a boy. I haven’t re-assessed and no doubt a stint of re-reading would lead to a change of mind for several of them.

No doubt there are many books on the list that you can’t imagine why they are there. No doubt, also, there are some that you can’t imagine why they are not there but many are probably absent because I haven’t read them as I would make no claims to be widely read.

I have restricted myself to one title per author, pseudonyms included.

I haven’t counted as I compiled the list but I think there are 81 titles there. I’m sure there are other I should add if they came to mind. In the meantime this listing should be regarded as a work in progress rather than the finished thing.

Eric Ambler: Passage of Arms (1959)

I read a lot of Ambler back in the ’60s but this was the one that gripped me more than the others.

H.C. Bailey: Call Mr Fortune (1920)

I bought an omnibus of the first four Mr Fortune short story collections. I started reading intending to just read this first book but ended reading all four straight off.

Francis Beeding: Death Walks in Eastrepps (1931)

I can’t remember the details but I remember enjoying it.

Nicholas Blake: The Beast Must Die (1938)

An author sets out to find the hit-and-run driver who killed his son.

Lawrence Block: A Stab In The Dark (1981)

The best of the earlyish Scudders.

Edward Boyd and Bill Knox: The View From Daniel Pike (1974)

Short stories about a Glasgow private eye. Boyd wrote the tv scripts Knox turned them into stories.

Ernest Bramah: Max Carrados (1914)

Classic short stories about a blind detective.

Howard Browne: The Taste Of Ashes (1957)

The best of Paul Pine, private detective.

Curt Cannon [1]: I’m Cannon — For Hire (1958)

I enjoyed this story of the down-and-out detective.

Sarah Caudwell: Thus Was Adonis Murdered (1981)

Witty badinage in the legal chambers and in Greece.

Raymond Chandler: Farewell My Lovely (1940)

My favourite of the Chandlers.

G. K. Chesterton: The Innocence of Father Brown (1911)

Another classic short story collection.

Erskine Childers: The Riddle of the Sands (1903)

Immaculate adventure/spy story

Agatha Christie: Death on the Nile (1938)

An intricately contrived crime that ties up the loose ends.

Tucker Coe: Kinds of Love, Kinds of Death (1966)

I enjoyed the whole Mitch Tobin sequence and this first one set the tone nicely.

John Collee: Paper Mask (1987)

The tale of a doomed hospital porter who steps out of his station.

J. J. Connington: Nemesis at Raynham Parva (1929)

Domestic crime set in the country, with a cunning twist. [2]

Freeman Wills Crofts: The Groote Park Murder (1925)

A pre-French Crofts but the intricate plot works.

Len Deighton: The Ipcress File (1962)

The spy novel becomes working class.

Carter Dickson [3]: The Judas Window (1938)

One of Carr’s intricate impossible crimes.

Warwick Downing: The Player (1974)

I’ve forgotten the details but I know I enjoyed it.

Arthur Conan Doyle: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892)

Probably Doyle’s best set of short stories. (I’m not chickening out by selecting The Complete SH.)

Friedrich Dürrenmatt: The Pledge (1959)

Short tale of a detective’s mental deterioration as he seeks a child killer.

Stanley Ellin: Mystery Stories (1956)

Excellent and varied set of short stories.

G. J. Feakes: Moonrakers and Mischief (1961)

A little weak in the plot but hilariously funny.

Dick Francis: Enquiry (1970)

My favourite among many excellent racing thrillers.

R. Austin Freeman: The Red Thumb Mark (1907)

The meticulous Thorndyke at his intricate best.

Stephen Greenleaf: Beyond Blame (1986)

My favourite of the Tanner books. The ending stood up which it often didn’t in Greenleaf’s other books, good as they were to read.

Michael Gilbert: Death in Captivity (1952)

Whodunit and PoW escape novel all in one book.

Donald Hamilton: Death of a Citizen (1960)

First in an excellent series.

Dashiell Hammet: Red Harvest (1928)

My favourite of his novels, otherwise I might have gone for a short story collection.

Cyril Hare: Tragedy at Law (1942)

Pettigrew and the murder of a judge on the circuit that the author knew so well.

Thomas Harris: Red Dragon (1981)

Excellent story with a captivating villain.

Jeremiah Healy: So Like Sleep (1987)

My favourite of the early Cuddy’s.

Patricia Highsmith: Deep Water (1957)

I enjoyed this murderous tale better than her more famous works.

Edward D. Hoch: Diagnosis Impossible (1996)

Excellent collection of ‘impossible’ crimes concerning Dr Sam Hawthorne.

E. W. Hornung: The Amateur Cracksman (1899)

First of the tales of Raffles. gentleman-thief.

Geoffrey Household: Rogue Male (1939)

The best thriller I have read.

Richard Hull: The Murder of My Aunt (1934)

Excellently humorous ‘inverted’ tale.

Stanley Hyland: Who Goes Hang? (1958)

The details have gone but I know I enjoyed this tales set in the House of Commons.

Francis Iles [4]: Malice Aforethought (1931)

Excellent inverted novel.

Dan Kavanagh: Putting the Boot In (1985)

The best book I have read set around football.

Harry Stephen Keeler: The Amazing Web (1929)

Typically intricate Keeler tale that all ties together neatly at the end.

Maurice Leblanc: The Confessions of Arsène Lupin (1912)

Amusing and intricate tales of the French rogue.

John le Carré: Call For the Dead (1961)

Excellent detective story set in the world of espionage.

Ira Levin: A Kiss Before Dying (1953)

Has the best single moment I can recall reading.

Dick Lochte: Sleeping Dog (1985)

Funny and yet enthralling p.i. tale.

Peter Lovesey: A Case of Spirits (1975)

Excellent impossible crime about the excellent Sergeant Cribb.

Arthur Lyons: All God’s Children (1975)

A very enjoyable p.i. tale with Jacob Asch.

John D. MacDonald: A Deadly Shade of Gold (1965)

I read, and enjoyed, the McGee’s a long while ago but this is the one I seem to remember enjoying most.

Philip MacDonald: The Nursemaid Who Disappeared (1938)

Colonel Gethryn on a case with very little to work on.

Ross Macdonald: The Underground Man (1971)

My favourite of the Lew Archer books.

Raymond Marshall [5]: Hit and Run (1958)

Outstanding first person tale of a man who is enticed and becomes wanted for murder.

L.A. Morse: The Old Dick

I enjoyed this tale of an elderly detective.

John Mortimer: Rumpole of the Bailey (1978)

The first collection of stories about the Old Bailey hack.

Sara Paretsky: Bitter Medicine (1987)

My favourite of the Warshawski’s.

Robert B. Parker: Paper Doll (1993)

Spenser finds the murderer of a businessman’s wife without Hawk’s help.

David Pierce: Down in the Valley (1989)

The first about private eye Vic Daniel.

Jeremy Pikser: Junk on the Hill (1984)

I’ve forgotten the details of this but I remember I enjoyed it.

Joyce Porter: Dover and the Unkindest Cut of All (1967)

Dover investigates forcible castrations.

Talmage Powell: The Girl’s Number Doesn’t Answer (1960)

The strongest of the five books about Tampa p.i. Ed Rivers

Bill Pronzini: Shackles (1988)

Nameless is imprisoned and left to die, while working out who his captor is.

Ellery Queen: The Glass Village (1954)

My favourite Queen though Ellery is not in it.

Patrick Quentin: Puzzle for Fiends (1946)

Intriguing tale of Peter Duluth institutionalised with amnesia.

Ruth Rendell: A Demon in my View (1976)

Excellent plot and beguiling story.

Sax Rohmer: The Mystery of Dr Fu-Manchu (1913)

I loved this as a youngster; Fu-Manchu dominates every page he is on.

James Sallis: The Long-Legged Fly (1992)

I enjoyed this first in the Lew Griffin series and the second, too, though they started to pall after that.

Sapper: The Female of the Species (1928)

Bulldog Drummond was racist and objectionable but as a boy I raced through his exploits. This was my favourite as he had to decipher a message to rescue his wife.

Gunnar Staalesen: At Night All Wolves Are Grey (1986)

Excellent, if bleak, p.i. tale set in Norway.

Rex Stout: In the Best Families (1950) [6]

Wolfe’s routine is disrupted in this tale.

Josephine Tey: The Franchise Affair (1948)

A slow build up to a revealing climax as a country solicitor defends two women accused of kidnapping.

Jim Thompson: Pop. 1280 (1964)

One of Thompson’s riveting tales of a descent into madness.

June Thomson: The Secret Files of Sherlock Holmes (1990)

Excellent Holmes short story pastiches.

Masako Togawa: The Lady Killer (1985)

A serial killer in Tokyo.

Peter Tremayne: The Return of Raffles (1981)

Excellent tale following Raffles’s return from the Boer War.

S. S. Van Dine: The Bishop Murder Case (1929)

Van Dine is out of favour nowadays but this is one I really enjoyed.

Roy Vickers: The Department of Dead Ends (1947)

Classic tales of cold cases revived from a single clue.

Henry Wade: Mist on the Saltings (1933)

A nicely turned out story in which things are as they seemed.

Edgar Wallace: The Fellowship of the Frog

Another author I read extensively as a boy. This is one of my favourites that I suspect might not stand up to a second reading.

Colin Watson: Hopjoy Was Here (1962)

A funny, yet involving detective story.

Charles Williams: Dead Calm (1963)

A riveting tale of skulduggery on the high seas.

FOOTNOTES:

1. aka Evan Hunter or Ed McBain

2. This is a title that should be read after sampling several of the earlier Connington’s

3. aka John Dickson Carr

4. aka Anthony Berkeley

5. aka James Hadley Chase

6. This is a title that should be read after sampling several of the earlier Nero Wolfe tales, especially And Be a Villain and The Second Confession.

Editorial Comment: I have one more list of favorite or “best” mysteries to go. I’ll post one from Curt Evans tomorrow. If you’ve been following his reviews on this blog, you won’t be surprised to know that his list consists solely of Golden Age British Detective Novels. Even with that restriction, his list is the longest: 120 books in all. So far.

Mon 4 Oct 2010

MY 100 “BEST” MYSTERIES

by DAVID L. VINEYARD

Steve suggested we might try our hands at a 100 best list, so here with some reservations is mine. Reservation number 1: I have limited myself to mystery and suspense novels, so no thrillers, adventure, or spy novels.

Number 2: I have no short story collections on the list — I couldn’t top the Queen’s Quorum anyway.

Number 3: I am skipping the early classics from The Moonstone to The Hound of the Baskervilles. For all practical purposes this list begins with the birth of the Golden Age which most would place with E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case. The books before that are deserving of a list of their own.

Also, I have limited myself to one title per writer though obviously some writers should have multiple entries.

The final reservation is that this is no “best” list. More a favorites list, and of course at different times there would be some variation. Some favorite writers don’t make the list because another, sometimes lesser, writer wrote one very good book. And though they wrote well after the cut off date I’m leaving R. Austin Freeman to the earlier period along with Conan Doyle and Chesterton.

And warning, this list is extremely eclectic.

It struck me too how many of these had been filmed so a * marks a film version.

With those caveats, herewith:

About the Murder of The Circus Queen by A. Abbott *

The Death of Achilles by Boris Akunin

Tiger in the Smoke by Margery Allingham *

Terror on Broadway by David Alexander

Perish By the Sword by Poul Anderson

Hell Is a City by William Ard

The Unsuspected by Charlotte Armstrong *

Murder in Las Vegas by W. T. Ballard

Death Walks in Eastrepps by Francis Beeding

Charlie Chan Carries On by Earl Derr Biggers *

The Beast Must Die by Nicholas Blake *

Bombay Mail by Lawrence G. Blochman *

No Good From a Corpse by Leigh Brackett

Green For Danger by Christianna Brand *

The Clock Strikes Thirteen by Herbert Brean

A Case for Three Detectives by Leo Bruce

The Screaming Mimi by Fredric Brown *

Asphalt Jungle by W. R. Burnett *

The Secret of High Eldersham by Miles Burton

Fast One by Paul Cain *

Circus Couronne by R. Wright Campbell

The Man Who Could Not Shudder by John Dickson Carr

Farewell My Lovely by Raymond Chandler *

Elsinore by Jerome Charyn

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie *

First Prize by Edward Cline

Stolen Away by Max Allan Collins

Brass Rainbow by Michael Collins

The Moving Toyshop by Edmund Crispin

The Wrong Case by James Crumley

Snarl of the Beast by Carroll John Daly

Sally in the Alley by Norbert Davis

The Poisoned Oracle by Peter Dickinson

To Catch A Thief by David Dodge *

My Cousin Rachel by Daphne Du Maurier *

End of the Game (aka The Judge and His Hangman) by Friedrich Duerrenmatt *

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco *

The Naked Spur by Charles Einstein *

The Eighth Circle by Stanley Ellin

L.A. Confidential by James Ellroy *

Mirage by Walter Ericson (Howard Fast) *

Double Or Quits by A. A. Fair

The Big Clock by Kenneth Fearing *

Death Comes to Perigord by John Ferguson

Isle of Snakes by Robert L. Fish

High Art by Rubem Fonseca *

King of the Rainy Country by Nicholas Freeling

Operation Terror by the Gordons *

Take My Life by Winston Graham *

Brighton Rock by Graham Greene *

It Happened In Boston by Russell Greenhan

The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett *

Violent Saturday by W. L. Heath *

Why Shoot a Butler by Georgette Heyer

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith *

Night Has 1000 Eyes by George Hopley (Cornell Woolrich) *

Flush as May by P. M. Hubbard

Ride the Pink Horse by Dorothy B. Hughes *

One Man Show by Michael Innes

An Unsuitable Job For a Woman by P. D. James *

The 10:30 From Marseilles by Sebastian Japrisot *

The Last Express by Baynard Kendrick

Night and the City by Gerald Kersh *

Fata Morgana by William Kotzwinkle

Murder of a Wife by Henry Kuttner

Headed for a Hearse by Jonathan Latimer *

Curtain for a Jester by Richard and Francis Lockridge

Let’s Hear it For the Deaf Man by Ed McBain *

Through a Glass Darkly by Helen McCloy

The Green Ripper by John D. MacDonald

The List of Adrian Messenger by Philip MacDonald *

Black Money by Ross Macdonald

Gideon’s Day by J. J. Marric (John Creasey) *

Died in the Wool by Ngaio Marsh

Guilty Bystander by Wade Miller *

A Neat Little Corpse by Max Murray *

Sleeper’s East by Frederic Nebel *

Let’s Kill Uncle by Rohan O’Grady *

Puzzle for Fools by Q. Patrick

Fracas in the Foothills by Eliot Paul

To Live and Die in L.A. by Gerald Petivich *

Shackles by Bill Pronzini

Cat of Many Tails by Ellery Queen *

Footprints on the Ceiling by Clayton Rawson

Trial by Fury by Craig Rice

The Erasers by Alain Robbe-Grillett *

The Nine Tailors by Dorothy L. Sayers *

So Evil My Love by Joseph Shearing *

Stain on the Snow (aka The Snow is Black) by Georges Simenon *

The Laughing Policeman by Maj Sjowall & Per Waloo *

Death Under Sail by C. P. Snow

Blues for the Prince by Bart Spicer

One Lonely Night by Mickey Spillane

Judas Inc. by Kurt Steel

Some Buried Caesar by Rex Stout

Rim of the Pit by Hake Talbot

The Bishop Murder Case by S. S. Van Dine *

Above the Dark Circus by Hugh Walpole

Death Takes the Bus by Lionel White

Death in a Bowl by Raoul Whitfield

Editorial Comment: Previously on this blog have been top 100 lists from Barry Gardner and Jeff Meyerson. Coming tomorrow is another such list from Geoff Bradley, editor and publisher of CADS (Crime and Detective Stories) . Thanks to all!

Sat 24 Jul 2010

A REVIEW BY MARYELL CLEARY:

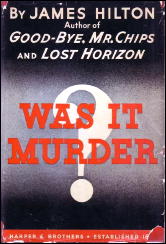

JAMES HILTON – Was It Murder? Paperback reprint: Bantam #29, 1946. Hardcover edition: Harper & Brothers, US, 1933. Other reprints include: Dover, trade paperback, 1979; Perennial Library, pb, 1980. First published as Murder at School, by Glen Trevor: Benn, UK, hardcover, 1931.

James Hilton’s only mystery is set in a boys’ school in England. It is interesting to compare it with Nicholas Blake’s mystery A Question of Proof, which has the same sort of setting. Both Hilton and C. Day Lewis, Blake’s real name wrote other kinds of literature and gained their primary reputation that way.

Blake, in his first detective story, gives us the picture of an entire school and its operations, while Hilton prefers to concentrate on one segment. Hilton shows us just a corner of the physical domain: the headmaster’s house, the home of one of the married masters, a dormitory, and glimpses of the chapel and the Circle, a path around the perimeter of the school.

His amateur detective, Colin Revel, is an “old boy” of Oakington, so it is not hard to find an excuse for his presence before there is widespread suspicion of murder.

Blake’s detective is called in by a master under suspicion after murder has very obviously been done. Yet both fit well into the schools, get along with masters and boys, and don’t seem out of place.

Revell is called in by the headmaster, Dr. Robert Roseveare when one of the younger boys is killed, apparently by acc1dent. Roseveare seems nervous, but as the investigation goes on and the accident seems to be precisely that, he is quite anxious to have Revell leave.

Then a second boy dies, a brother of the first, in another ‘accident.’ Revell hastens back; the police are called in by the boys guardian, and evidence is found that this time it is murder.

Suspicion naturally falls on the master, who inherits all the boys’ wealth. But there is no evidence. And there is a deathbed confession, and the police leave. But Revell is not satisfied and stays on.

The cast of characters is small; suspicion never goes far from the one person. There is less a hunt for evidence than a delving into the high emotions of the people: love, jealousy, greed, fear, pride.

Sophisticated readers of the 70s may guess the surprise solution before the end, but the writer keeps up the drama and the suspense; we can’t be sure. And when the final revelations come, they draw together all the skeins, and one puts down the book with a sigh of satisfaction.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 2, No. 6, Nov-Dec 1979.

Bibliographical Note: It is not quite true, perhaps, that this book was Hilton’s only mystery, as there are three others listed under his name in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Two are included only marginally, however, and the third may be a crime story without being a mystery, per se. For completeness, though, here’s the complete list:

HILTON, JAMES. 1900-1954.

-Rage in Heaven (n.) King 1932

Knight Without Armour (n.) Benn 1933

Was It Murder? (n.) Harper 1933. See: Murder at School (Benn 1931), as by Glen Trevor.

-We Are Not Alone (n.) Macmillan 1937

Wed 14 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[14] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

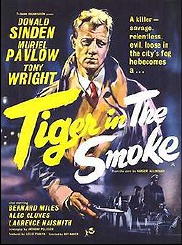

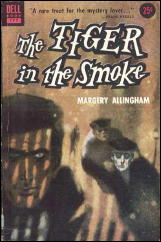

MARGERY ALLINGHAM – The Tiger in the Smoke. Chatto & Windus, UK, hardcover, 1952. Doubleday, US, hc, 1952. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback, including (shown): Dell 777, pb, ca.1954; Avon T-530, pb, ca.1961; Bantam, pb, 1985.

Film: As Tiger in the Smoke. J. Arthur Rank, 1956. Tony Wright, Donald Sinden, Alec Clunes, Muriel Pavlow, Bernard Miles, Laurence Naismith, Christopher Rhodes. Screenplay by Anthony Pelissier based on the novel by Margery Allingham. Director: Roy Ward Baker.

The Tiger in the Smoke is a rarity among genre novels — a book that is also a first class novel. I can only think of a handful that fill that category: Nicholas Blake’s Death and Daisy Bland and A Private Wound, Michael Innes’s The New Sonia Wayward, Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye…

That Tiger in the Smoke also features Albert Campion, one of the major figures of the Golden Age of Detective fiction is all the more remarkable.

Not that Tiger is a product of the Golden Age. For much of the novel we know who the criminal is and what his motive is. The novel is far more interested in the question of good and evil than simply who dunnit.

The book wasn’t recognized as a masterpiece initially — at least not by everyone. Some critics seemed confused by Allingham stretching the boundaries of the detective story. In retrospect it has gained the reputation it deserves, though it sits outside the whole canon of Campion stories despite his presence and that of Inspector Charlie Luke, who had been introduced in More Work for the Undertaker, Amanda Campion, and the ever present Lugg.

Notably the film leaves Campion, Amanda, and Lugg out of the story completely and they aren’t particularly missed.

Three characters dominate Tiger: Jack Havoc is a former commando, war hero, deserter, and wild card, a Teddy Boy with a streak of violence and a persona of evil unleashed, “killing recklessly and all for nothing”; Canon Avril is a quiet gentle man who tends his flock and as part of his job finds himself confronting Jack, “…with an approach to life which was clear sighted yet slightly off-centre.”

Finally there is the location itself, a portion of London known as the Smoke, St. Petersgate Square (based on Linden Gardens and Notting Hill Gate), where “…ramshackle stalls roofed with flapping tarpaulin and lit with naked bulbs jostled each other down each side of the littered road” and there are “…a lot of good houses going down, and a lot of good people too”.

There is one other character important to the novel. The fog; those post war fogs which twined about London like deadly serpents and caused hundreds of deaths. Fog in London is almost a character in itself in the novel.

The fog slopped over its low houses like a bucketful of cold soup over a row of dirty stoves.

The theme of the novel was first expressed by Allingham in The Oaken Heart (M. Joseph, 1941):

Active evil is more incomprehensible in this two-part-perfect world than active good, and so it ought to be.

The novel follows Havoc’s crimes and the police hunt for him as he terrorizes the Smoke on a rampage involving his hunt for a treasure he believes is hidden in St. Odile. Eventually Havoc and Avril confront each other and Avril tries to warn Havoc that his “Science of Luck” is a false god:

“Evil be thou my Good, that is what you have discovered. It is the only sin which cannot be forgiven because when it is finished with you you are not there to forgive.”

And it is to Allingham’s credit that while Avril is wholly good, even Havoc is not wholly evil. In the end he is destroyed as much by that touch of good he cannot avoid as by all his evil actions and plans.

It isn’t as if Campion has nothing to do in the novel. In fact he has one Great Detective moment, and a memorable one as it turns out, because during it Lugg gets to express the frustration of every Watson in the genre and no small number of readers.

Campion and Amanda are in their car with Lugg driving, and in response to a question from Amanda Campion gives one of those obscure Great Detective answers where he doesn’t quite answer the question about a written clue and Lugg explodes:

“Oh, for God’s sake! … Drivin’ this and listenin’ to you, it’s like being up to me eyes in the creek. What ’ad the perisher wrote down?”

You just know that Watson, Archie Goodwin, and even Captain Hastings felt like expressing something very close to that a thousand times.

Havoc and the Canon aren’t the only characters in the book worth noting. Young Inspector Luke is new to the area and caught up in the brutal violence fired by Jack Havoc’s quest for his treasure; Geoffrey Levitt and Meg Eliginbroddie, a young war widow, are lovers caught up in the danger; Doll is a gang leader challenged and endangered by Havoc’s reckless crimes; and Mrs. Cash, Havoc’s mother is often the voice of the Smoke itself.

In the film Tony Wright was Havoc; Laurence Naismith, Canon Avril; Alec Clunes, Charlie Luke; and Bernard Miles was Doll. Sadly the film is too little seen and hard to find, but it is well worth catching if you get the chance. Roy Ward Baker’s other films include Highly Dangerous and The October Man both excellent suspense films (and both with screenplays by Eric Ambler).

The inevitability of Havoc’s fall doesn’t interfere with the suspense as the novel moves along tightening the suspense and involving the reader more deeply.

Tiger in the Smoke is one you won’t easily forget or put aside when you have finished it. Jack Havoc will linger in your imagination in a way human monsters sometimes do long after the theatrics of a Hannibal Lector have been consigned to the same sub-basement of the imagination as Bruce the Shark or other childish fears.

Allingham manages to capture real evil in all its attraction and repulsion just as she counters it with a good man who is neither cliched nor unworldly. For that alone this is a first class novel and not only a detective novel — though it is a good one of those too.

And it really is a remarkable novel to have been written by one of the unquestioned queens of the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

Editorial Comment. 07-15-10. I’ve done a search for Tiger in the Smoke on DVD, and if you have a multi-region player, then you’d be in luck, if you were looking for it. I found a boxed set of Donald Sinden movies on Amazon-UK, and Tiger is one of them.

Others: DAY TO REMEMBER, YOU KNOW WHAT SAILORS ARE, THE BEACHCOMBER, MAD ABOUT MEN, ABOVE US THE WAVES, AN ALLIGATOR NAMED DAISY, EYEWITNESS, THE BLACK TENT, ROCKETS GALORE, and MIX ME A PERSON. All for less than 18 pounds.

Tue 22 Jun 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Of all the authors who in the years after World War II moved mystery fiction “from the detective story to the crime novel,” perhaps the most influential American woman was Patricia Highsmith (1921-1995).

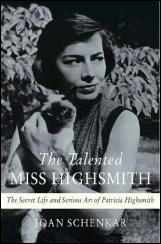

Certainly she’s the only one to have received so much critical attention after her death: first Andrew Wilson’s biography in 2003, more recently Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss Highsmith, which isn’t a conventional biography but more an exploration of Highsmith’s obsession-torn mind and emotions and how they spilled over into novels like Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

If you think Cornell Woolrich was something of a psychopath and a creep, you don’t know the meaning of those words till you’ve encountered Highsmith.

Both, of course, were homosexual. I gather from Schenkar’s book that Highsmith, who was born in Texas and came of age in the feverish New York of the World War II years and went through lovers with the fury of a Texas twister, was never terribly comfortable with being a lesbian.

Woolrich was perhaps the most deeply closeted, self-hating homosexual male author that ever lived. Both wound up worth several million but often acted as if they were penniless. Both lived mainly on booze, cigarettes and coffee, with peanut butter added to the diet in Highsmith’s case.

Both bequeathed their copyrights and other property to institutions, not human beings. Woolrich left an autobiographical manuscript (Blues of a Lifetime) which is full of obvious fiction; Highsmith left 8000 pages of notebooks which, as Shenkar demonstrates, are also pockmarked with falsifications.

But there were notable differences too. Just to mention one, Highsmith was fixated on possessions, keeping everything (except any paper trail leading back to the seven years she had spent in her twenties writing scripts for comic books like Spy Smasher and Jap Buster Johnson), while Woolrich kept nothing, not even copies of his novels and stories.

It’s most unlikely that the two ever met. Woolrich read very little crime fiction but appeared regularly in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in the Fifties and Sixties and may have read Highsmith’s EQMM stories.

We know she read the magazine steadily and, in her book Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, devoted almost a full page to Woolrich’s “Murder After Death” (EQMM, December 1964).

Why did she single out this rarely reprinted and never collected tale? Perhaps she saw something akin to her own evil protagonists in Georg Mohler, a loser at the game of love who turns to crime for emotional revenge.

When the wealthy and lovely Delphine rejects him for law student Reed Holcomb and then dies a sudden but natural death, Mohler concocts a laughably dumb plot to sneak into the funeral parlor, inject poison into her body and frame Holcomb for murder.

Woolrich’s detail work is sloppy and implausible and his climactic twist, like those in several of his earlier stories, comes straight out of James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. But the scene where Mohler hides in the funeral home and posthumously poisons his lover’s corpse is a gem of poetic horror.

If any single element in the tale deserved Highsmith’s attention it was this one. In fact she spent most of the page summarizing the plot, calling it a “quite well-done gimmick story” with “an elaborate but quite entertaining and believable scaffolding….” Go figure.

It was a gimmick—the two men in Strangers on a Train (1950) agreeing (or did they?) to exchange murders — that first made crime fiction readers (not to mention Alfred Hitchcock) take notice of the not yet 30-year-old Highsmith.

Later authors including Nicholas Blake and Fredric Brown worked their own variations on the theme. But who remembers its first appearance in the genre?

Mum’s the Word for Murder (1938) uses very much the same gimmick, although here it involves three murders, not two, and is saved till the solution rather than employed as a springboard.

The byline on this long-forgotten book was Asa Baker but the author’s real name was Davis Dresser and his best-known pseudonym was Brett Halliday, which he used for the all but endless adventures of Miami PI Michael Shayne, beginning in 1939, a year after Mum’s the Word came out.

As chance would have it, much of both novels is set in Texas, where both Dresser and Highsmith spent several of their formative years.

Wed 23 Dec 2009

This list of Christmas mysteries, compiled by Caryn Wesner-Early, first appeared in Mystery*File 40, December 2003, and being all of six years old, is surely long out of date by now. Don’t that dissuade you from finding one or more of these to read over the next twelve days or so!

Adamson, Lydia. A Cat in the Manger

Adamson, Lydia. A Cat in the Wings

Adamson, Lydia. Cat on Jingle Bell Rock

Adamson, Lydia. A Cat Under the Mistletoe

Adrian, Jack. Crime at Christmas: A Seasonal Box of Murderous Delights

Alexander, David. Shoot a Sitting Duck

Allen, Garrison et al. Murder Most Merry

Allen, Michael. Spence and the Holiday Murders

Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity’s Christmas

Babson, Marion. The Twelve Deaths of Christmas

Baker, Nikki. Long Goodbye

Barron, Stephanie. Jane and the Wandering Eye

Beaton, M.C. A Highland Christmas

Bernhardt, William. The Midnight Before Christmas

Black, Gavin. A Dragon for Christmas

Blades, Joe and Jeffrey Marks, eds. A Canine Christmas

Blake, Nicholas. The Corpse in the Snowman

Borthwick, J.S. Dude on Arrival

Boylan, Eleanor. Pushing Murder

Braun, Lillian Jackson. The Cat Who Turned On and Off

Braun, Lillian Jackson. The Cat Who Went Into the Closet

Brett, Simon. Christmas Crimes at Puzzle Manor

Cameron, Eleanor. The Mysterious Christmas Shell (children’s)

Cavanna. Betty. The Ghost of Ballyhooly (children’s)

Christian, Mary Blount. Sebastian (Super Sleuth) and the Santa Claus Caper (children’s)

Christie, Agatha. Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (Murder for Christmas, A Holiday for Murder)

Churchill, Jill. A Farewell to Yarns

Churchill, Jill. The Merchant of Menace

Clark, Carol Higgins. Iced

Clark, Mary Higgins. All Through the Night

Clark, Mary Higgins. Silent Night

Clark, Mary and Carol Higgins. Deck the Halls

Constantine, K.C. Upon Some Midnight Clear

Corcoran, Barbara. Mystery on Ice

Cornwell, Patricia. From Potter’s Field

Cornwell, Patricia. Scarpetta’s Winter Table

Cramer, Kathryn and David G. Hartwell (eds.) Christmas Ghosts

Crowleigh, Ann et al. Murder Under the Tree (anthology)

Daheim, Mary. The Alpine Christmas

Daheim, Mary. Nutty As a Fruitcake

Dalby, Richard, ed. Crime for Christmas (anthology)

Dalby, Richard, ed. Mystery for Christmas (anthology)

D’Amato, Barbara. Hard Christmas

Davidson, Diane. Tough Cookie

Daws, Jeanne M. The Body in the Transept

Dawson, Janet. Nobody’s Child

Delaney, Joseph. The Christmas Tree Murders

Dobson, Joanne. Quieter Than Sleep

Douglas, Carole Nelson. Cat in a Golden Garland

Drummond, John Keith. ‘Tis the Season to Be Dying

Duffy, James. The Christmas Gang

Eberhart, Mignon G. Postmark Murder

Egan, Lesley. Crime for Christmas

Elkins, Aaron. A Deceptive Clarity

Emerson, Kathy Lynn. Face Down Upon an Herbal

Erskine, Margaret. House of the Enchantress

Faglia, Leonard and David Richards. 1 Ragged Ridge Road

Fairstein, Linda. The Deadhouse

Farrell, Kathleen. Mistletoe Malice

Ferrars, E.X. Smoke Without Fire

Ferris, Monica. A Stitch In Time

Fletcher, Jessica and Bain, Donald. A Little Yuletide Murder

Fletcher, Jessica and Bain, Donald. Murder She Wrote: Manhattans and Murder

Flynn, Brian. The Murders Near Mapleton

Foley, Rae. Where is Mary Bostwick?

Frazier, Margaret. The Servant’s Tale

Gano, John. Inspector Proby’s Christmas

Godfrey, Thomas, ed. Murder for Christmas (2 vols. – anthology)

Goodman, Jonathan, ed. The Christmas Murders (anthology)

Grafton, Sue. E Is for Evidence

Granger, Anne. A Season for Murder

Greeley, Andrew M. The Bishop and the Three Kings

Greenberg, Martin H., ed. Holmes for the Holidays

Greenberg, Martin H., ed. More Holmes for the Holidays

Greenberg, Martin H. and Carol-Lynn Rossel Waugh, eds. Santa Clues (anthology)

Grimes, Martha. The Man With a Load of Mischief

Gunn, Victor. Death on Shivering Sand

Haddam, Jane. Festival of Deaths (Hanukkah)

Haddam, Jane. Not a Creature Was Stirring

Haddam, Jane. A Stillness in Bethlehem

Hager, Jean. The Last Noel

Hall, Robert Lee. Benjamin Franklin and a Case of Christmas Murder

Hardwick, Richard. The Season to Be Deadly

Hare, Cecil. An English Murder

Harris, Charlaine. Shakespeare’s Christmas

Harris, Lee. The Christmas Night Murder

Hart, Carolyn. Sugarplum Dead

Hart, Ellen. Murder in the Air

Hay, M. Doriel. The Santa Klaus Murder

Heald, Tim, ed. A Classic Christmas Crime (anthology)

Healy, Jeremiah. Right to Die

Hemlin, Tim. A Catered Christmas

Hemlin, Tim. If Wishes Were Horses…

Hess, Joan. A Holly, Jolly Murder

Hess, Joan. O Little Town of Maggody

Heyer, Georgette. Envious Casca

Hirsh, M.E. Dreaming Back

Holland, Isabelle. A Fatal Advent

Holmes for the Holidays (anthology)

Hunter, Fred. Ransome for a Holiday

Hunter, Fred. ‘Tis the Season for Murder: Christmas Crimes

Iams, Jack. Do Not Murder Before Christmas

Innes, Michael. Christmas at Candleshoes

Jaffe, Jody. Chestnut Mare, Beware

Jahn, Michael. Murder on Fifth Avenue

Jordan, Cathleen. A Carol in the Dark

Jordan, Jennifer. Murder Under the Mistletoe

Kane, Henry. A Corpse for Christmas (Homicide at Yuletide)

Keene, Carolyn. A Crime for Christmas (children’s)

Kelner, Toni L.P. Mad As the Dickens

Kelly, Mary C. The Christmas Egg

Kitchin, C.H.B. Crime at Christmas

Koch, Edward I. and Wendy Corsi Staub. Murder on 34th Street

Langton, Jane. The Shortest Day

Lake, M.D. Grave Choices

Lambert, Elisabeth. The Sleeping House Party

Lewin, Michael Z. Family Planning

Lewis, Gogo and Seon Manley, eds. Christmas Ghosts (anthology)

Livingston, Nancy. Quiet Murder

McBain, Ed. And All Through the House

McBain, Ed. Downtown

McBain, Ed. Sadie When She Died

McClure, James. The Gooseberry Fool

McGown, Jill. Murder at the Old Vicarage

McKevett, G.A. Cooked Goose

MacLeod, Charlotte, ed. Christmas Stalkings (anthology)

MacLeod, Charlotte. Convivial Codfish

MacLeod, Charlotte, ed. Mistletoe Mysteries (anthology)

MacLeod, Charlotte. Rest You Merry

Mallowan, Agatha Christie. A Star Over Bethlehem and Other Stories

Manson, Cynthia, ed. Christmas Crimes (anthology)

Manson, Cynthia, ed. Murder Under the Mistletoe (anthology)

Manson, Cynthia, ed. Mystery for Christmas and Other Stories (anthology)

Markham, Marion M. The Christmas Present Mystery (children’s)

Maron, Margaret. Corpus Christmas

Marsh, Carole. Christmas Tree Mystery

Marsh, Ngaio. Tied Up in Tinsel

Meier, Leslie. Christmas Cookie Murder

Meier, Leslie. Mail Order Murder

Meier, Leslie. Mistletoe Murder

Meredith, D.R. Death By Sacrilege

Meredith, David William. The Christmas Card Murders

Meyers, Annette. These Bones Were Made for Dancin’

Miers, Earl. The Christmas Card Murders

Mortimer, John Clifford, ed. Murder at Christmas (anthology)

Moyes, Patricia. Who Killed Father Christmas? and Other Unseasonable Demises

Muller, Marcia. Both Ends of the Night

Muller, Marcia. There’s Nothing to Be Afraid Of

Murder Most Merry (anthology)

Murder Under the Tree (anthology)

Murray, Donna Huston. The Main Line is Murder

Nordan, Robert. Death Beneath the Christmas Tree

O’Marie, Sister Carol Anne. Advent of Dying

O’Marie, Sister Carol Anne. Murder in Ordinary Time

Page, Katherine Hall. Body in the Bouillon

Peters, Ellis. Monk’s Hood

Pulver, Mary Monica. Original Sin

Queen, Ellery. The Finishing Stroke

Raphael, Lev. Burning Down the House

Ray, Robert J. Merry Christmas Murdock

Resnick, Mike and Martin H. Greenberg, eds. Christmas Ghosts (anthology)

Robb, J.D. Holiday in Death

Roberts, Gillain. The Mummers’ Curse

Robinson, Peter. Past Reason Hated

Ruell, Patrick. Red Christmas

Sawyer, Corrine Holt. Ho-Ho Homicide

Serafin, David. Christmas Rising

Shannon, Dell. No Holiday for Murder

Sibley, Celestine. Spider in the Sink

Smith, Barbara Burnett. Mistletoe from Purple Sage

Smith, Barbara Burnett et al. ‘Tis the Season for Murder

Smith, Frank. Fatal Flaw

St. John, Wylly Folk. The Christmas Tree Mystery (children’s)

Trochek, Kathy Hogan. Midnight Clear

Waugh, Carol-Lynn Rossel, ed. The Twelve Crimes of Christmas (anthology)

Weir, Charlene. A Cold Christmas

Welk, Mary V. A Deadly Little Christmas

Williams, David. Murder in Advent

Windsor, Patricia. Christmas Killer

Windsor, Patricia. A Very Weird and Moogly Christmas

Wingfield, R.D. Frost at Christmas

Witting, Clifford. Catt Out of the Bag

Wolzien, Valerie. Deck the Halls with Murder

Wolzien, Valerie. ‘Tis the Season to Be Murdered

Wolzien, Valerie. We Wish You a Merry Murder

Woolley, Catherine. Libby’s Uninvited Guest

… And Checking It Twice:

In the letter column for Mystery*File 43, Jeff Meyerson added the following:

Agatha Christie, “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding” (title novella in ss collection)

Agatha Christie, “Christmas Adventure” in While the Light Lasts (apparently the original, shorter version of the above).

Georges Simenon, “Maigret’s Christmas” (title story in ss collection)

Bill Crider, Terence Faherty, Wendi Lee, Aileen Schumacher, Murder, Mayhem and Mistletoe (paperback original; four Christmas-related stories)

[ Jeff goes on to say: ]

Caryn should also be aware of a very entertaining pamphlet published in 1982 by Albert Memendez called Mistletoe Malice: The Life and Times of the Christmas Murder Mystery (Silver Spring, MD, Holly Tree Press). The 35 pages goes through various Christmas mysteries and includes a checklist of 89 books, of which about 60 (at fast glance) are not on Caryn’s list. I think the majority of her list is post-1982 titles.

[ Later. ] These are the ones not listed on Caryn Wesner-Early’s list in M*F 40. Obviously, most of these are older books, while much of the list in M*F consists of books published since Mistletoe Malice was published in 1982.

Anthony Abbot, About the Murder of a Startled Lady

” ” About the Murder of Geraldine Foster

North Baker, Dead to the World

W. A. Ballinger, A Corpse For Christmas

Charity Blackstock, The Foggy, Foggy Dew

Nicholas Blake, Thou Shell of Death

” ” The Smiler With the Knife

Carter Brown, A Corpse for Christmas

Leo Bruce, Such is Death (Crack of Doom)

W. J. Burley, Death in Willow Pattern

Thomas Chastain, 911

Noel Clad, The Savage

Constance Cornish, Dead of Winter

Alisa Craig (Charlotte MacLeod), Murder Goes Mumming

Joel Dane, The Christmas Tree Murders

Frederick C. Davis, Drag the Dark

Mildred Davis, Tell Them What’s Her Name Called

” ” Three Minutes to Midnight

Spencer Dean, Credit for a Murder

Carter Dickson (John Dickson Carr), The White Priory Murders

“Diplomat”, The Corpse on the White House Lawn

Todd Downing, The Last Trumpet

Francis Duncan, Murder for Christmas

Mary Durham, Keeps Death His Court

Jefferson Farjeon, Mystery in White

Elizabeth X. Ferrars, The Small World of Murder

Ian Fleming, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

Rae Foley, The Hundredth Door

Leslie Ford, The Simple Way of Poison

Roger Gouze, A Quiet Game of Bambu

Dulcie Gray, Dead Giveaway

Dashiell Hammett, The Thin Man

Lee Hays, Black Christmas

Edith Howie, Murder for Christmas

John Howlett, The Christmas Spy

Cledwyn Hughes, The Inn Closes For Christmas (He Dared Not Look Behind)

Fergus Hume, The Coin of Edward VII

Alan Hunter, Landed Gently

Michael Innes, A Comedy of Terrors (There Came Both Mist and Snow)

Glenn Kezer, The Queen is Dead

Kathleen Moore Knight, They’re Going to Kill Me

Alfred Lawrence, Columbo: A Christmas Killing

Ted Lewis, Jack Carter’s Law

Richard Lockridge, Dead Run

Miriam Lynch, Crime for Christmas

Ed McBain, The Pusher

” ” Ghosts

Helen McCloy, Two-Thirds of a Ghost

” ” Mr. Splitfoot

” ” Burn This

Anne Nash, Said With Flowers

Stuart Palmer, Omit Flowers

Jack Pearl, Victims

Ellery Queen, The Egyptian Cross Mystery

Patrick Quentin, The Follower

M. P. Rea, Death of an Angel

Jonathan Stagge, The Yellow Taxi

Elizabeth Atwood Taylor, The Cable Car Murder

Laurence Treat, Q as in Quicksand

Charles Marquis Warren, Deadhead

If your favorite seasonal mystery (or mysteries) is (are) not here, that’s what the comments box is for!

Tue 24 Nov 2009

Posted by Steve under

Inquiries[2] Comments

In my comment following Marv Lachman’s review of Nicholas Blake’s Malice in Wonderland, I pointed out that the book had, over the years, been published under four different titles:

1) Malice in Wonderland (Collins)

2) The Summer Camp Mystery (Harper-US)

3) Malice with Murder (Pyramid-US)

4) Murder with Malice (Carroll & Graf-US)

I also wondered whether or not this was a record for the most titles one mystery novel has been published under.

A few days ago I received the email below from British bookseller Jamie Sturgeon. This is not a contest, since while he didn’t quite give the answers, he revealed enough so that anyone with access to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV will be able to discover what he came up with right away. But for the sake of anyone who doesn’t have a handy copy of CFIV or who’d like to give it a try on their own, I’ll wait to reveal all until the first comment to this post.

Hi Steve,

I’ve not managed to come up with a book with five titles but there are two John Creasey Inspector West books that both have four different titles.

Regards,

Jamie

Mon 7 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Rufus King’s Florida Short Stories,

by MIKE GROST.

Rufus King’s last works were a series of short stories set among the rich in Miami and its environs; many of them were published by Ellery Queen in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.

Although King’s use of Miami has been compared to John D. MacDonald, it also recalls the Florida stories of Philip Wylie. In addition to setting, other Wylie-like features include an emphasis on botany and Florida plant life, amateur detectives who discover sinister conspiracies, and the use of international intrigue.

Three of the more interesting of these stories are discussed below.

“Malice in Wonderland” (EQMM, October 1957) contains some of King’s most magical atmosphere and mise-en-scéne. The tale is written as a sort of sinister fairy tale, full of events that can be given a supernatural interpretation.

King used rich and brilliant color in these Miami stories, especially in his descriptions of deserts. In “Malice”, we see exotic ice cream dishes that are described in full color. By the way, “Malice in Wonderland” was originally the title of a 1940 novel by Nicholas Blake. When Ellery Queen first published King’s short story in EQMM, he thought the phrase would make a good title for the story, and he used it, with the permission of both Blake and King.

“The Seeds of Murder” (EQMM, August 1959) is an impossible crime tale. There are clues that allow one to deduce who the killer is, at least after you have figured out how the crime was done.

This is the paradigmatic detective situation in such Ellery Queen works as The Spanish Cape Mystery (1935). This story seems even closer to Queen than to Van Dine. It focuses on the sort of rich, eccentric, multi-talented extended family of adults that often pops up in Queen tales.

“The Faces of Danger” (EQMM, November 1960) is written in a partly summarized style. This style recalls, to a degree, that used by Ellery Queen in his Q.B.I. stories and parts of his Calendar of Crime.

However, King’s approach is less condensed than Queen’s. Queen used it to tell a whole story in less than ten pages, while King’s novella sprawls over forty. Both writers like to use the approach to invoke, and partially lampoon, the clichés of storytelling.

In both, there is a certain sophistication of tone, a suggestion of sophisticated satire on conventional plotting. There is the feeling in both writers in which a game is being played by the author. In this game, the author tries to come up with the “best” response by the characters to each new situation.

For example, a body might be discovered, and the next step in the story is tell what the characters are going to do. Sometimes this response is original, sometimes conventional. The more conventional responses are presented to the reader with irony, using a summarized statement to invoke the chief elements of the familiar situation.

Less familiar responses are sometimes contrasted with the clichés of fiction, to underline the originality of the situation. So a description will contain both its true content, and its opposite.

The whole effect is of a game the author is playing with the reader, challenging them to guess how the characters will behave in any new situation, suggesting a duel of wits between the writer and the reader over the most original response to any event in the plot.

This is in keeping with, but further extends, the basic active reading approach of most mystery fiction. In most mystery tales, the reader is not supposed to sit back, and just let the events of the tale wash passively over them.

Instead, the reader is challenged to deduce the true solution of the mystery at every turn. The reader, in turn, constantly monitors the author’s plot for logical consistency, and surprise. This sort of active readership is applied to every event in the mystery plot.

In Queen and King, this approach is extended not just to the mystery puzzle plot itself, but every fictional development in the story: the characters’ attitudes, responses to events, social conditions and backgrounds, police procedure, the romance subplot, details of the social milieu such as butlers and mansions, in short, every aspect of the story. This allows active readership as a universal response to the tale.

King always likes verbal fireworks in his tales; such an approach gives him many opportunities in that direction. It allows for an exuberant writing style, one filled with elaborate turns of phrase and much wit.