Search Results for 'Raymond Chandler'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Wed 30 Jan 2019

SELECTED BY DAVID VINETARD:

RAYMOND CHANDLER “Guns at Cyrano’s.” Ted Carmady #1. Novelette. First published in Black Mask January 1936 (with the leading character named Ted Malvern). Collected in: Five Murderers, Avon, paperback, 1944; Red Wind, World, hardcover, 1946; The Simple Art of Murder, Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1950; Pick-Up on Noon Street, Pocket, paperback, 1952; Stories and Early Novels, Library of America, hardcover, 1995. TV episode: Season 2 Episode 4 of Philip Marlowe, Private Eye, 18 May 1986 (with Powers Boothe as Philip Marlowe).

Ted Carmady liked the rain; liked the feel of it, the sound of it, the smell of it. He got out of his LaSalle coupe and stood for a while by the side entrance to the Carondelet, the high collar of his blue suede ulster tickling his ears, his hands in his pockets and a limp cigarette sputtering between his lips. Then he went in past the barbershop and the drugstore and the perfume shop with its rows of delicately lighted bottles, ranged like the ensemble in the finale of a Broadway musical.

“Guns at Cyrano’s†is one of the many short works written by Raymond Chandler for the pulps between 1929 and the publication of his first story “Blackmailer’s Don’t Shoot†and 1938 and the publication of The Big Sleep, the first Philip Marlowe novel. It is neither the best nor the worst of the lot (certainly not as good as the John Dalmas stories, particularly “Red Windâ€), not even the best of the stories written in the third person (“Spanish Blood†and “Nevada Gas†are both better).

I’ll go further, it isn’t even the best of the stories featuring Carmady (here known as Ted Carmady).

I am not damning with faint praise though, because it is my personal favorite of the early stories, a pulpy B-movie of a boozy rainy noir tale replete with women no better than they have to be, a hero who isn’t so noble he’s boring or hard to believe in, a few innocents, and of course that famous man who walks into the room with a gun just as the lull starts to set in.

Carmady, at least as presented here — and you will be forgiven if you question if this is the same Carmady of “Killer in the Rain†— has money and lives well, unlike anyone else in Chandler’s oveure he is not a private detective (he used to be, and even identifies himself as one at one point, but a rich private eye goes against almost everything Chandler ever wrote elsewhere) nor a good cop or house dick, but instead the son of a father who got his money in a clearly stated illegal way, meaning his son knows a lot of shady people and has a romantic notion that maybe he ought to make up for his father’s sins by helping people in trouble:

“Okey,†he said thinly. “I’m nosey. So what? This is my town. My dad used to run it. Old Marcus Carmady, the People’s Friend; this is my hotel. I own a piece of it. That snowed–up hoodlum looked like a life–taker to me. Why wouldn’t I want to help out?â€

Here he is headed for the hotel room he lives in when he spots a victim lying in an open doorway.

She lay on her side, in a sheen of steel–gray lounging pajamas, her cheek pressed into the nap of the hall carpet, her head a mass of thick corn–blond hair, waved with glassy precision. Not a hair looked out of place. She was young, very pretty, and she didn’t look dead.

Carmady slid down beside her, touched her cheek. It was warm. He lifted the hair softly away from her head and saw the bruise.

“Sapped.†His lips pressed back against his teeth.

Frankly at this point you wouldn’t be too shocked if Carmady turned out to have a sobriquet like the Saint or the Toff. Only the language is different, and maybe the attitude, the milieu is pretty much the same.

The Dame, all women in these stories are some shade of Dames, good, bad, classy, murderous, or saintly, is a chanteuse named Jean Adrian (“I do a number at Cyrano’s.â€), no better and no worse than life and men have made her, who likes his whiskey and is loathe to admit she was sapped or explain the.22 he finds beside her.

Seems Miss Adrian has a boy friend who is a fighter, Duke Targo, and the Boys would like him to drop a fight, and they are trying to get to her through him. Naturally no Chandler hero can let that knightly quest go unmet.

Of course that knightly quest is far from simple this being Chandler, involving a State Senator being blackmailed, a fixer named Doll Conant (His clothes looked as if they had cost a great deal of money and had been slept in.), an innocent victim to be avenged, and that gunfight at Benny Cyrano’s club from the title.

Before it is over there is more gunplay (more in this single story than all the Marlowe novels put together), a few beatings, plenty of the kind of tough poetic dialogue Chandler was famous for, and a moral of sorts. It all makes for a satisfying pulp tale with the air of a good B movie and with those little touches that make even early Chandler such a pleasure to read.

As I said, I like this story much more than it deserves for what it is. I’ve even seen it suggested it is the weakest of the Chandler stories, but it just happens to fit me for some reason, which is all any of us can ask of any story.

They went through silent streets, past blurred houses, blurred trees, the blurred shine of street lights. There were neon signs behind the thick curtains of mist. There was no sky.

If, like me you are a sucker for that particular brand of music, “Guns at Cyrano’s†hits all the notes on key, sonata for Thompson Machine Gun in B-Flat.

Tue 20 Dec 2016

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

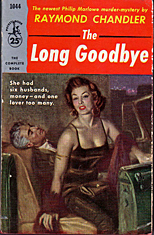

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Long Goodbye. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1954. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including Pocket 1044, 1955.

THE LONG GOODBYE. United Artists, 1973. Elliott Gould, Nina van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, Mark Rydell, Henry Gibson, David Arkin, Jim Bouton. Screenplay by Leigh Brackett, based on the novel by Raymond Chandler. Director: Robert Altman.

I discovered Raymond Chandler back in High School, re-read him after College, and still dip into his work now and again. But I’ve kind of resisted re-visiting The Long Goodbye, which I recalled as somewhat flabby and overrated. Well, I approached it again a few years ago with interest and a bit of trepidation, wondering if I’d finish it. Then in the first couple pages I came across the line “She gave him a look that should have stuck out his back four inches,” and my ticket was stamped for the ride.

I wouldn’t call Goodbye flabby; it is/was over-rated by critics impressed by Chandler’s carping John-D-MacDonald-style about the society we live in, the sorry state of television and gays in the art world — all much less impressive fifty-odd years later. Goodbye lacks the vigor of The Big Sleep, and it’s not as poignant as The High Window, but Chandler keeps it moving with his own often-imitated prose and lively characters like Big Willie Magoon and Mendy Menendez, a flamboyant gangster who gives the piece a sense of motion even when there’s not much going on. I have to say, though, Goodbye really needs these colorful touches, because this plot re-e-ally takes its time unspooling. In all, I’m glad I took another look at it, but it’s far from his best.

In 1973 Robert Altman and Leigh Brackett (who co-adapted The Big Sleep for the movies in ’45) made a movie of The Long Goodbye which was generally scorned by critics, savaged by Chandler fans and ignored by the public — I’ve always loved it.

In those days before noir came back in style, it was artistically impossible to do a hard-boiled mystery like they used to – look at the sorry attempts with James Garner and Robert Mitchum – so Altman/Brackett turned “Raymond Chandler’s savagely disenchanted outlaw-within-the-law†(Bosley Crowther) or the “Knight Without Meaning†(Charles Gregory) into a faintly comic, out-of-step icon.

The sensitivity is still there, along with the Instant Bullshit Detector, but the showy hardness is replaced by bemused detachment and Popeye-mutter. It works, enacted by Elliott Gould and a superb cast including Nina Van Pallandt, Sterling Hayden, director Mark Rydell (great in the flashy-gangster role) Henry Gibson(!) and Arnold Schwarzenegger(try to spot him.)

I’m not a big fan of the late Robert Altman, but (as yet another critic pointed out) this movie shares a lot of qualities with Alphaville and Point Blank: dis-location of space and time, use of décor as landscape and landscape as décor, absurd violence, and stock characters who refuse to act like stereotypes… in all a film kinky, off-beat and surprisingly faithful.

As an interesting sidelight, Long Goodbye was done for television in 1954, or thereabouts with Dick Powell as Marlowe on an hour-long show called Climax – the same show that first did Casino Royale.

And another interesting bit: When this film came out I was dating two women, and dating them pretty seriously — seriously enough that I couldn’t afford to keep it up very long, so I took them to The Long Goodbye (on different nights; this was the 70s, not the 90s) to see how they reacted: One loved it, the other asked me how I could possibly enjoy such a film, and told me never to take her to another like it.

In due course, I married the second one.

Sat 12 Nov 2016

DASHIELL HAMMETT “The Gutting of Couffignal.” Black Mask, December 1925. [+] RAYMOND CHANDLER “Red Nevada.” Black Mask, June 1935. Both stories have been reprinted many times, including a joint appearance in Great Action Stories, edited by William Kittredge & Steven M,. Krauzer. Mentor Book, paperback original, May 1977.

I came across the Kittredge & Krauzer paperback one day a short while ago, and I decided to bring it along on a recent cross-country flight I made. I’m glad I did. Other than the stories above, it also includes stories by Mickey Spillane (“I’ll Die Tomorrow”), Len Deighton, Fredric Brown, Robert L. Fish and a number of others, the names of most of whom I’m sure would be readily recognizable to everyone who visits this blog on a regular basis.

But the two authors featured at the top of those listed on the front cover are Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, the two most famous proponents (if not out and out creators) of the “hard boiled” school of writing, bar none. And while the two stories the editors selected are alike in some way, in others they are as different as night and day.

The plot of “The Gutting of Couffnignal” is the simpler and more straight forward of the two. The Continental Op has been hired to watch a table filled with wedding gifts overnight on a island in San Pablo Bay off the California shore, connected only by a single bridge.

An easy job, or it would have been if a gang of robbers armed with machine guns and other weapons doesn’t attack the island, blowing up the bank and a jewelry store with dynamite, and killing scores of people in the process. With the help of a family of Russian expatriates, the Op assumes the responsibility of coming to the aid of the entire island, and that he does.

The action is fast and furious, but the Op shows that all the while he’s on the move, he’s thinking too, and the ending is as hard boiled an ending as you imagine. It’s a story that once begun, you won’t put down until you’re done, with Hammett fully in charge with clear,clean prose.

“Nevada Gas,” Raymond Chandler’s tale of personal warfare between some top gangsters in the city of Los Angeles, is as hard boiled as Hammett’s, but the story is a lot more complicated and filled with some subtle nuances that can easily take you more than one reading before you decide you’ve caught them all.

Two scenes in particular stand out. In the first a heavy set crooked lawyer named Hugo Candless is taken for a ride in a limousine mocked up to look like his own, but it is not, and what’s more, it’s rigged to delivered a dose of fatal gas to anyone who finds himself trapped in the back seat.

The second, almost unnecessary to the plot finds a guy named Johnny De Ruse, who’s also the main protagonist, having escaped the same trap himself, going to a gambling place and faking his way into seeing the one responsible by making a scene in a crooked casino room.

As opposed to the Hammett story, Chandler’s zigs and zags, giving the reader only brief glimpses of a connected tale, but connected it is. Chander’s prose is lot more ornate, and the ending is much more quiet, but to my mind, it’s equally effective.

Question: If you’ve read both, which story did you like better? Which author tickles your fancy more?

Fri 1 Jul 2016

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

RAYMOND CHANDLER – Five Murderers. Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #19, digest-sized paperback, 1944; New Avon Library #63, paperback, 1944.

A brightly packaged confection of early stories by Raymond Chandler, including his first, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot” (1933) and his first first-person narration, “Goldfish” (1936).

Well, they read just like early efforts of a major mystery stylist: the prose is highly-patterned and a bit gaudy, the action scenes plentiful and effective, and the characters sometimes try to behave like something other than figures on a pulp cover.

The only consistent problem is with the stories themselves, which are mostly over-plotted. Chandler sets up a case (usually missing jewels) then side characters come on and make cryptic comments, bodies turn up, heads are sapped, new actors walk on and off, secrets get shared, lies lied, and (in Chandler’s own words) two men come through the door with guns in their hands.

This is a lot of to-do for a sixty-page story, and after about 55 pages of it, everything gets sorted out with a wild shoot-’em-up that leaves the bad guys conveniently dead and the good guys still up and about to close the case.

Pretty awful stuff, really. The wonder is that Chandler’s gifts for sharp characterization and telling prose make it all so pleasant to swallow — and I mean, these are almost compellingly readable. Now and again he slips up — in “Blackmailers” a young starlet opines “They look as if they only existed alter dark, like ghouls. The people are dissipated without grace, sinful without irony.” and it’s all too dearly the author talking, not the character — but in the main these pulp tales are catchy little gems and well worth looking at.

Bibliographic Notes: None of the five stories feature Philip Marlowe; all first appeared in Black Mask magazine. The other three stories are “Guns at Cyrano’s” (1936), “Nevada Gas” (1935) and “Spanish Blood” (1935).

Sun 3 Aug 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

My July column, the longest I’ve ever written, was completely devoted to the Mike Hammer TV series of 1958-59 but there are a couple of related items that I couldn’t squeeze in last time. I trust no Hammerhead will mind if I begin with these.

Two questions surrounding the series caught my attention as I was fiddling with the column. First, was there a Hammer pilot episode and if so which was it? The order of original broadcast in New York or any other city doesn’t help because it was different in every market and completely up to the station owning the local rights. Copyright registration dates don’t help either, nor does the order in which they appear on the recently released DVD set. If the episodes had production numbers, I haven’t been able to find them.

However, I think I’ve solved the puzzle while slowly making my way through the set. Throughout the series the role of Hammer’s friendly enemy Captain Pat Chambers is played by Bart Burns. But in one early segment there’s a plainclothes cop who’s referred to only as Pat but is clearly meant to be Chambers. The actor who plays him is not Bart Burns but Ted De Corsia, who also played Sergeant Velie for much of the run of the Adventures of Ellery Queen on radio.

The episode is “Death Takes an Encore,†directed by Richard Irving and written by Frank Kane based on one of his short stories about New York PI Johnny Liddell (“Return Engagement,†Manhunt, February 1955, collected in Johnny Liddell’s Morgue, Dell pb #A117, 1956). For my money, that was the pilot.

The second question also involves Frank Kane. Back in the late Forties he wrote around 45 scripts for that classic radio series The Shadow, and for several years there have been rumors that at least one of his Hammer scripts was a rewrite of one of his Shadow scripts. But which?

I believe I’ve solved that puzzle too. Another early episode written by Kane, “Letter Edged in Blackmail,†shares a springboard with Kane’s Shadow script “Etched with Acid†(March 17, 1946): the protagonist in both tries to shut down a racket in which wealthy women with heavy gambling debts are forced to fake robberies of their own jewels. As neither Mike Hammer nor The Shadow would ever dream of saying: Q.E.D.

Death has claimed two actors who were well known for having played TV detectives. Efrem Zimbalist Jr. was the first to go. He died on May 2 at age 95, reportedly while mowing the lawn of his house in the horse-ranching community of Solvang, California.

People of my generation first got to know Zimbalist on the Warner Bros. TV series 77 Sunset Strip (1958-64), in which he starred as ultra-suave PI Stuart Bailey. No sooner had that series left the air than he started playing Federal agent Lewis Erskine on the even longer-running The FBI (1965-74).

When I met him — very briefly, at a film festival in Memphis — he was over 80 and still looked great. Judging from the photos of him I found on the Web, he still looked great in his 90s. Way to go! May we all be so lucky.

The other recently deceased tele-icon was James Garner, who at age 86 was found dead in his Los Angeles home on July 19. Like Zimbalist he was best known for two long-running TV series but his were in different genres.

His earliest claim to fame was as star of the Warner Bros. Western series Maverick (1957-63) but his interest for us stems from his years playing an un-macho PI in The Rockford Files (1974-80).

In his autobiography The Garner Files (2011) he claimed that Bret Maverick and Jim Rockford were basically the same character, but he never said and probably never knew that the character from which both were sort of spun off was an icon of U.S. detective fiction, namely that quintessential American wiseass Archie Goodwin.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: if only there had been a Nero Wolfe movie with the middle-aged Orson Welles as Wolfe and the young Garner as Archie!

Both Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip were created by the same man, who was also a co-producer and, as John Thomas James, a frequent scriptwriter for The Rockford Files .

He first came to attention, however, as a mystery novelist. Roy Huggins (1914-2002) debuted in the genre with The Double Take (1946), whose protagonist, PI Stuart Bailey, was a character and first-person narrator owing a great deal to Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and very different from the suave and perhaps a bit bland Bailey of 77 Sunset Strip.

Anthony Boucher’s review for the San Francisco Chronicle (February 3, 1946) was spot on as usual: “Mr. Huggins adds nothing to the established hardboiled formula but does an unusually able job within its possibly overfamiliar frame.â€

At that time, with Dashiell Hammett having written nothing since The Thin Man (1934), “the established hardboiled formula†meant Chandler. The latter may not have read The Double Take himself but he clearly found out about it and, as witness his letter to fellow pulp veteran Cleve F. Adams (September 4, 1948), he was not amused.

“I don’t know Roy Huggins and have never laid eyes on him. He sent me an autographed copy of his book … with his apologies and the dedication he says the publishers would not let him put in it. In writing to thank him I said his apologies were either unnecessary or inadequate and that I could name three or four writers who had gone as far as he had, without his frankness about it …. I personally think that a deliberate attempt to lift a writer’s personal tricks, his stock in trade, his mannerisms, his approach to his material, can be carried too far — to the point where it is a kind of plagiarism, and a nasty kind because the law gives no protection…. Somebody who read Huggins’ book told me that it was full of scenes which were modeled in detail on scenes in my books, just moved over enough to get by.â€

Somebody else informed Chandler that “the publishers told Huggins, in effect, that it was bad enough for him to steal my approach and my method or whatever, but stealing my characters was going a little too far. I understand there was some rewriting, but cannot vouch for any of this.â€

The letter to Adams can be found in Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981), pp. 125-126. This is the only reference to Huggins in the index to MacShane’s book, but a careful reader will find Chandler revisiting the incident in later correspondence. Writing to spy novelist and later Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt on November 16, 1952, he says:

“As you may know, writers like Dashiell Hammett and myself have been widely and ruthlessly imitated, so closely as to amount to a moral plagiarism…. I have had stories taken scene by scene and just lightly changed here and there. I have had lines of dialogue taken intact, bits of description also word for word. I have no recourse. The law doesn’t call it plagiarism.â€

Exactly nine months later, on September 16, 1953, writing to a master at his alma mater Dulwich College, he adds a bit more detail to the story.

“A few years ago a man wrote a story which was a scene by scene steal from one of mine. He changed names and incidents just enough to stay inside the law…. The publisher to whom the book was sent demanded indignantly of the agent submitting it how he dared send them a book by Chandler under a pseudonym without saying so. When he learned that I had not had anything to do with the book he demanded certain changes to tone down the blatancy of the imitation and then published it. It did very well too.â€

These quotations come respectively from pp. 334 and 352 of MacShane’s collection.

Huggins’ Hollywood career began when The Double Take sold to the movies and he was hired to write the screenplay for what was released as I Love Trouble (1948), with Franchot Tone as Bailey. By the time Chandler died, in 1959, Huggins had created Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip and both series were prime-time hits, but the creator of Philip Marlowe watched very little TV and may never have known that a sardonic prophecy he had made in his letter to Cleve Adams had come true:

“More power to Mr. Huggins. If he has been traveling on borrowed gas to any extent, the time will come when he will have to spew his guts into his own tank.â€

Which is precisely what Huggins did.

Fri 6 Jun 2014

RAYMOND CHANDLER’S FAVOURITE CRIME WRITERS AND CRIME NOVELS – A List by Josef Hoffmann.

In his letters and essays Chandler frequently made sharp comments about his colleagues and their literary output. He disliked and sharply criticized such famous crime writers like Eric Ambler, Nicholas Blake, W. R. Burnett, James M. Cain, John Dickson Carr, James Hadley Chase, Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L. Sayers, Mickey Spillane, Rex Stout, S. S. Van Dine, Edgar Wallace. A lot of Chandler’s criticism was negative, but he also esteemed some writers and books. So let’s see, which these are.

A problem is that he sometimes had a mixed or even inconsistent opinion. When the positive aspects predominate the negative ones I have taken the writer or book on my list.

The list follows the alphabetical order of the names of the mystery writers. Each name is combined with (only) one source (letter, essay) for Chandler’s statement. I refer to the following books: Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, edited by Frank MacShane, Columbia University Press 1981 (SL); Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, University of California Press 1997 (RCS); The Raymond Chandler Papers: Selected Letters and Non-Fiction 1909 – 1959, edited by Tom Hiney & Frank MacShane, Penguin 2001 (RCP); “The Simple Art of Murder,” in: The Art of the Mystery Story, edited by Howard Haycraft, Carroll & Graf 1992.

I am rather sure that the list is not complete: It does not include all available sources nor all possible writers and books.

THE LIST:

Adams, Cleve, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Anderson, Edward: Thieves Like Us, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Armstrong, Charlotte: Mischief, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Balchin, Nigel: The Small Back Room, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 18, 1945 (SL)

Buchan, John: The 39 Steps, letter to James Sandoe, Dec. 28, 1949 (RCS)

Cheyney, Peter: Dark Duet, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 14, 1949 (RCS)

Coxe, George Harmon, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Crofts, Freeman Wills, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Davis, Norbert, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (SL)

Faulkner, William: Intruder in the Dust, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Nov. 11, 1949 (SL)

Fearing, Kenneth: The Big Clock, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Mar. 12, 1949 (SL); The Dagger of the Mind, The Simple Art of Murder

Fleming, Ian, letter to Ian Fleming, Apr. 11, 1956 (SL)

Freeman, R. Austin: Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight; The Stoneware Monkey; Pontifex, Son and Thorndyke, letter to James Keddie, Sep. 29, 1950 (SL)

Gardner, Erle Stanley, letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, Jan. 29, 1946 (but not as A. A. Fair, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939) (SL)

Gault, William, letter to William Gault, Apr. 1955 (SL)

Hammett, Dashiell, The Simple Art of Murder

Henderson, Donald: Mr. Bowling Buys a Newspaper, letter to fredeeric Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Holding , Elisabeth Sanxay: Net of Cobwebs, The Innocent Mrs. Duff, The Blank Wall, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Oct. 13, 1950 (RCS)

Hughes, Dorothy, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Irish, William (Cornell Woolrich): Phantom Lady, letter to Blanche Knopf, Oct. 22, 1942 (SL)

Krasner , William: Walk the Dark Streets, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Macdonald, Philip, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Macdonald, John Ross: The Moving Target, letter to James Sandoe, Apr. 14, 1949 (SL)

Maugham, Somerset: Ashenden, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Dec. 4, 1949 (SL)

Millar, Margaret: Wall of Eyes, letter to Alex Barris, Apr. 16, 1949 (RCS)

Nebel, Frederick, letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

O’Farrell, William: Thin Edge of Violence, letter to James Sandoe, Aug. 15, 1949 (SL)

Postgate, Raymond: Verdict of Twelve, The Simple Art of Murder

Ross, James: They don’t dance much, letter to Hamish Hamilton, Sep. 27, 1954 (SL)

Sale, Richard: Lazarus No. 7, The Simple Art of Murder

Smith, Shelley: The Woman in the Sea, letter to James Sandoe, Sep. 23, 1948 (SL)

Symons, Julian: The 31st of February, letter to Frederic Dannay, Jul. 10, 1951 (SL)

Tey, Josephine: The Franchise Affair, letter to James Sandoe, Oct. 17, 1948 (RCS)

Waugh, Hillary: Last Seen Wearing, letter to Luther Nichols, Sep. 1958 (SL)

Whitfield, Raoul: letter to George Harmon Coxe, Dec. 19, 1939 (SL)

Wilde, Percival: Inquest, The Simple Art of Murder.

Sun 1 Sep 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Hello again! I won’t attempt to describe the health problems that forced me to abandon this column and just about everything else these past few months, but they seem to be behind me now and I’m ready to take up where I left off. Care to join me?

Not long before I put the column on hiatus, I learned from Fred Dannay’s son Richard that I’d made a mistake in Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, and I can’t think of a better place to correct it than here.

On page 241 of the book I state that the 1968 Queen novel The House of Brass was written by Avram Davidson from an outline by Fred. It’s true that Davidson was commissioned to and did expand Fred’s outline to book length, but that’s only a small part of the story, which is told in full in the Dannay papers, archived at Columbia University.

Among the House of Brass documents are: (1) two different drafts of Fred’s synopsis, one running 74 pages, the other 61; (2) Davidson’s expansion of the synopsis, which runs 181 pages; (3) two copies of the 266-page version of the novel written by Manny Lee after the Davidson version was rejected; (4) two copies of the final draft of the novel, which runs 275 typed pages. These facts are indisputable, and I thank Richard Dannay for sharing them with me.

As I documented in my February column, we know from Manny’s letter to Fred dated November 3, 1958 that he was at work turning a Dannay synopsis into a new novel but had been put behind schedule by health problems. (Whether these included the onset of writer’s block remains unknown.)

We also know that the book in question was not The Finishing Stroke, which had been published much earlier in 1958 and was the last novel in what I’ve called Queen’s third period. So what happened to the book Manny was working on near the end of the year?

I can envision three possibilities. (1) Fred gave up on it completely. (2) He gave up on it as a novel and he or another writer turned it into the novelet “The Death of Don Juan†(Argosy, May 1962; collected in Queens Full, 1965). (3) Manny went back to the project after recovering from writer’s block and it was published as Face to Face (1967).

My own guess, which is speculative but (I hope!) informed, is the third possibility. With that as my premise, I offer the following timeline.

Late 1958 or early 1959 — Manny develops writer’s block and is unable to continue expanding the latest Dannay synopsis into a novel.

1961 or 1962 — A decision is made to bring in other writers to perform Manny’s traditional function.

1963 — Publication of The Player on the Other Side, written by Theodore Sturgeon from Fred’s synopsis.

1964 — Publication of And on the Eighth Day, written by Avram Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1965 — Publication of The Fourth Side of the Triangle, written by Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1966? — Davidson expands Fred’s synopsis into The House of Brass, but Fred and Manny reject his version and the project is shelved.

1966 or 1967 — Manny recovers from writer’s block and finishes his work on the project that was left incomplete back in the late Fifties. This book is published as Face to Face (1967).

1967 or 1968 — Manny completely rewrites the rejected Davidson version of The House of Brass, which is published under that title in 1968.

The final Queen hardcover novels — Cop Out (1969), The Last Woman in His Life (1970), and A Fine and Private Place (1971), whose publication Manny did not live to see — were written by the cousins without input from outsiders, Fred preparing the plot synopses as usual and Manny expanding them to book length.

As editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Fred had reprinted dozens of the pulp stories of Dashiell Hammett but just one tale by Raymond Chandler and that only after his death. Of course the vast majority of Chandler’s short fiction was too long for EQMM’s requirements, but from Fred’s point of view the most serious problem with the creator of Philip Marlowe was that, unlike Hammett, he had a pervasive tendency to get lost in his own plot labyrinths. In fact he once said that plot didn’t matter to him, only the individual scenes did.

This tendency can be seen as far back as his first published story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot†(Black Mask, December 1933; collected in Red Wind, World 1946, and in Stories and Early Novels, Library of America 1995).

Trying to make sense of this story is like trying to nail jelly to a wall. One of the main characters is Landrey, a gambler and racketeer who earlier in his life had tried to launch a Hollywood career. In those days he had had an affair with Rhonda Farr, a young beauty who had become a major star. Apparently wanting to rekindle the romance, Landrey pretends that Rhonda’s love letters to him had been stolen and has his underworld buddies demand blackmail money from her. Then he hires the story’s protagonist, a PI named Mallory, to thwart the blackmailers and recover the letters.

All these events have taken place before the story begins. Chandler opens with a nightclub scene where Mallory pretends to have the letters himself and, hoping to force the blackmailers to go after him, demands $5,000 from Rhonda. (What would he have done if she had said “Show me you have them�) Chandler never makes up his mind whether Rhonda had asked Landrey to help get her letters back.

At pages 71 and 106 of the Red Wind collection and pages 7 and 37 of the Library of America volume it seems she did, at pages 111 and 42 respectively it seems she didn’t. If she didn’t, how could Landrey have known she was being blackmailed unless he was behind it himself?

At no point does Chandler provide any details about how the letters were stolen. In fact at pages 104-105 and 36-37 respectively it’s hinted that Landrey had returned the letters long ago and that they’d been stolen not from him but from her. To make matters even more chaotic, he for no earthly reason is carrying the letters in his own pocket on the night of the action!

Simultaneously with the fake blackmail plot, Landrey has arranged for Rhonda to be kidnaped and held for ransom so that he can rescue her and earn her eternal gratitude. Apparently none of his underlings are ever privy to his overall plan, but a remark of Mallory’s — “When the decoy worked I knew it was fixed†(pp. 112 and 43 respectively) — suggests that in some mystic manner our sleuth knew the truth almost from the get-go.

Somehow, although again Chandler spares us any details, Landrey’s partner Mardonne is involved in the master scheme, and Mallory miraculously discovers this aspect of the plot too (pp. 115 and 46 respectively). Small wonder that Mardonne (on pp. 112 and 43 respectively) remarks “A bit loose in places.â€

Parsing other Chandler stories will have to be done by someone else. Life’s too short.

How better to celebrate one’s recovery from serious illness than with one of the immortal works of Michael Avallone? The Flower-Covered Corpse (1969) is rife with the scrambled sentences that are his unique claim to fame but I’ll limit myself to a handful. The “I†in these quotations is New York PI Ed Moon, who is to detectives what Ed Wood was to directors.

I had never heard of Louis La Rosa. Didn’t know him from Robert J. Kennedy.

Blood played tag in my little grey cells.

“….Hep you may be but you are unitiate….â€

The mad evening had come to its final, inexorable totem pole of weird unreality.

More marbles scattered across the floor of what was left of my brain.

Right after War Two, he had plunged into the Police Academy bag and come up with an apple pie in each hand.

I didn’t have a client except myself and my own neck.

He tried to smile, still huddling his lovely fortune cookie.

Femininity and Melissa Mercer are blood sisters.

The .22 spit like a sneeze.

I said a handful and a hand has five fingers so I guess I should have stopped halfway through my list. But there’s something about Avalloneisms that almost forces me to say — again and again and again — “Just one more.†I hope you didn’t mind too much.

Sat 28 Jul 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

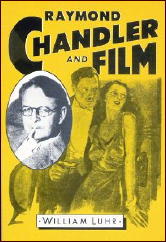

WILLIAM LUHR – Raymond Chandler and Film. Frederick Ungar, hardcover/softcover, 1982; bibliography and index, photographs, filmography. Florida State University, trade paperback, 1991.

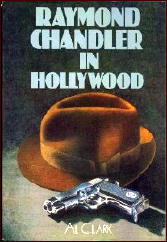

AL CLARK – Raymond Chandler in Hollywood. Proteus, hardcover/softcover, 1983; index, filmography. Silman-James Press, trade paperback, 1996.

I have paper editions of both these books: the Luhr is a 5-1/2 x 8″ yellowback, the cover sporting a portrait of Chandler set into an oval frame next to a pulp illustration; the Clark is a large-sized 8 x 10-3/4″ book, the cover featuring a brown hat with a revolver resting on the brim.

The Luhr pages are densely packed with text in small type, while the Clark is profusely illustrated with stills, lobbycards and other advertising material for the films. Luhr is an associate professor of English and film at St. Peter’s College, and Al Clark is a Spanish-born publicist and magazine editor who is currently creative director of the Virgin Records group, based in London.

The copy for Clark’s biography is probably written by him and is a tongue-in-cheek view of his life; Luhr’s credentials are presented soberly. The casual reader is likely to assume that Luhr is writing a serious study of Raymond Chandler’s Hollywood career and that Clark has put together an album for the film buff.

In fact, both books are valid contributions to the literature on Chandler’s Hollywood years. Luhr’s approach is largely analytical, a close reading of his films. Clark went to Los Angeles where he interviewed people involved in the films and people who knew Chandler, and his narrative is a mixture of production information and film analysis.

Clark unfortunately only cites his sources in his preface: there are neither notes nor bibliography. He seems more sensitive than Luhr to information furnished by people like Leigh Brackett, but both men communicate their enjoyment of the films and of Chandler’s fictional world, and I would not want to be without either book.

The layout on the Clark book is handsome, and the stills, not the tiny postage stamps one often sees, are generously displayed in an attractive format. I compared the two accounts of The Long Goodbye, and while they are not perfectly congruent they are in general agreement, with, as one would expect, Luhr going into greater detail about the film and Clark more enlightening on the actual production. He incorporates a lengthy interview with Nina Van Pallandt into the chapter, and it is the insight furnished into the making of the film that makes Raymond Chandler in Hollywood a more intimate look at the Raymond Chandler film world.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 7, No. 2, March-April 1983.

Thu 5 Jan 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

As a novice widower I find myself thinking of three other mystery writers who lost wives to Mister Death. The first name that springs to mind in this connection is Raymond Chandler (1888-1959), who was so devastated by the death of his wife Cissie that he tried to shoot himself in his bathroom.

Being blind drunk at the time, he missed his target. “She was the music heard faintly at the edge of sound…†he said of Cissie. “She was the light of my life, my whole ambition. Anything else I did was just the fire for her to warm her hands at.â€

Next comes Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), whom I never met but have been associated with for most of my life. He married the former Hazel Goodwin in 1919 and they were together until she died of cancer in May 1960.

During the months of her final illness and after her death he was unable to write fiction, but he continued sending out his off-the-wall “Walter Keyhole†newsletters to just about everyone whose address he had.

He called them polychromatic or multitinctorial cartularies since each page was printed on paper of a different color. We who have lived into the computer age recognize them as the functional equivalent of a blog. It cost him as much as $50 to have each installment prepared by a professional typing service and mailed out en masse.

I have originals or photocopies of 188 of these, which a few years ago I organized and offered to a panting public as The Keeler Keyhole Companion (2005). Among the hundreds of topics he touched on was his life as a lonely widower in his early seventies, “a guy who lives on canned Campbell’s soups and canned Sultana pork and beans.â€

Here’s his account of the “long lonely Thanksgiving holiday†in 1962. “We [he often uses the royal we in these cartularies] had our choice of having 3 soft-boiled eggs (only thing we can cook) as a dinner, then seeing the Three Stooges conk each other over the heads [at the local movie house], or of having 3 soft-boiled eggs as a dinner and re-reading Keyser’s Mathematical Philosophy. You guess!â€

I now feel closer to that genuine mad genius than ever before. He was only a year or two older at his wife’s death than I at Patty’s. He sold the old house they had lived in for decades and moved into an apartment hotel, while I’ve recently bought a condo and put my own Toad Hall on the market. I’m no better at cheffery than Harry was but have the advantage of living in the age of that fantastic contraption known as the microwave.

The third author in whose moccasins I now walk became a widower not once but twice. Fred Dannay (1905-1982), better known as Ellery Queen, married the former Mary Beck in 1926. She died of cancer on July 4, 1945, leaving Fred with two small children to raise.

In 1947 he married the former Hilda Wiesenthal, who was ten or eleven years younger than he and was the daughter of a cousin of Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal. She died in 1972, also of cancer.

By that time I had come to know Fred well and he had become the closest thing to a grandfather I had ever known. I went through this awful period of his life with him. There’s a photograph of him taken at this time which shows the empty devastated face of a man waiting for the dark to claim him.

Just as Keeler had married again a few years after Hazel’s death, so did Fred a few years after Hilda’s. I got to know Thelma Keeler well and am convinced that she saved her husband’s life. I also have no doubt that Fred’s third marriage, to the former Rose Koppel, saved his. Will I luck out in my final years as they did?

I apologize for devoting so much of this column to death but I really don’t have much choice at the moment. Less than a week before Christmas I learned that I’d lost one of my closest mystery-loving friends.

Bob Briney was something of a universal genius. Physically he evoked Orson Welles or Nero Wolfe but was soft-spoken and totally without their irascibility and moved with a certain gingerliness as if he were afraid he’d crush something if his movements were more forceful.

He was born near Benton Harbor, Michigan in December 1933 and spent most of his academic career in Massachusetts, at Salem State University. He earned a Ph.D. in mathematics and recovered from the ordeals of his dissertation and orals, so he told me, by reading most of the novels of John Dickson Carr in less than a month.

Like the clever men of Oxford in The Wind in the Willows, he “knew all that was to be knowed‗about mystery fiction, fantasy, s-f, horror, Westerns, just about every form of popular fiction you can name, plus ballet and opera and movies and classical music and so much more.

His ability to keep prodigious masses of data in perfectly organized form would have shamed many a computer. He wrote prolifically and with dry wit about books and authors, assiduously collected works in the genres he loved — every room in his large house including the bathroom was a library first and foremost — and corresponded with Sax Rohmer, P.G. Wodehouse, John Creasey and countless other authors.

It was pure pleasure to read his commentary or listen to his conversation. We started corresponding in the late Sixties, thanks mainly to Al Hubin and The Armchair Detective, and met for the first time in 1970 when I took a bus from New Jersey to a science fiction convention in Manhattan that he was attending.

Beginning in 1980 he followed in Keeler’s footsteps by putting out the pre-computer equivalent of a blog, which he called Contact Is Not a Verb (a famous line from one of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novels) and kept going until September 2006, a grand total of 149 issues, of a copy of every one of which I am a proud possessor.

Bob developed diabetes and in the fall of 1990, when I was a visiting professor in New Jersey, had to have some of his toes amputated. Unable to climb the stairs of his own house, he was sleeping in a hospital bed installed on the ground floor. I traveled to Salem by Amtrak and spent a long weekend playing housekeeper: schlepping cartons around so he could access the classical music he loved, taking his clothes to the laundry, even cooking us a few meals (for whose quality I will not vouch).

Until a few years ago we would rendezvous every summer at the Pulpcon in Dayton, Ohio. Then unaccountably this shy but gregarious man dropped out of sight. Almost no one heard a word from him or knew anything about his health.

Finally, just a few days before Christmas, I learned he’d been found dead in his house late in November. He had no immediate family. As of this writing I don’t know the cause, or what will happen to the vast library he had accumulated over the decades. All I know is that he was one of the most brilliant and memorable people in my life.

Bouchercon, Philadelphia, 1989. Me (Steve Lewis), Art Scott, Bob Briney, George Kelley, and Mike Nevins. Photo taken by Ellen Nehr.

Bouchercon, New York, 1983. Ellen Nehr and Bob Briney.

Bouchercon, Chicago, 1984. Marv Lachman, Bob Briney, Ellen Nehr and Steve Stilwell.

Many thanks to Art Scott for providing the photos above.

Sun 23 Jan 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

BYRON PREISS, Editor – Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe: A Centennial Celebration. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1988. Softcover editions: Perigee Press, 1990; ibooks, 1999. [Note that the latter adds a new introduction, two new stories, and a map of Philip Marlowe’s Los Angeles.]

Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe: A Centennial Celebration may be the only anthology I choose to list in my Crime Fiction Bibliography. Chandler was born in 1888, created Philip Marlowe, and the world — at least the crime fiction world — has never been the same. So some of the current top practitioners here pay tribute to both.

Marlowe stars in all twenty-three stories, set explicitly in years from 1935 to 1959, and they resonate not so much with Chandler’s writing style (which most of the authors don’t try to imitate) as with the times and places, with the ambiance of the private eye on the Chandlerian mean streets.

Some stories are distinctly more effective than others, but in the main this is quite enjoyable. And at the end, in “The Pencil,” Chandler himself shows us all how it should be done.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 4, Fall 1989.