Search Results for 'woolrich'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Sat 13 Oct 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

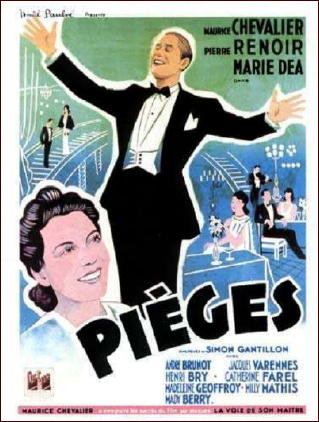

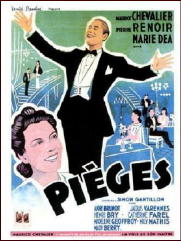

Since my last column I’ve seen Pièges, the French film from 1939 with so many strange links to Cornell Woolrich, and discovered even more of the same. I’ll limit myself here to three.

First of all, the movie is episodic in just the way so many of Woolrich’s best-known novels are episodic. It’s impossible that director Robert Siodmak and the screenwriters borrowed the structure from a Woolrich novel of that sort since all of those novels, beginning with The Bride Wore Black (1940), postdate Pièges.

Could the filmmakers have known of Woolrich’s first use of episodic structure in the long 1937 novelet “I’m Dangerous Tonight� Barely possible but most unlikely since that tale remained buried in the pulps for decades and wasn’t collected until 1981.

Secondly, for just a minute or two, beginning with Marie Dea’s discovery of her vanished girlfriend’s bracelet in Maurice Chevalier’s desk, Pièges evokes the classic Woolrich situation where the protagonist is made to seesaw back and forth between believing the person he or she loves is innocent and accepting the evidence of the other’s guilt. The earliest Woolrich story in this vein is “The Night Reveals†(1936) so the filmmakers could have known of it.

Third, when Chevalier in Pièges is put on trial for murder, director Robert Siodmak covers the scene in just a few impressionistic fragments. Woolrich in Phantom Lady (1942) covers the trial of Scott Henderson in somewhat the same way: prosecutor’s closing argument, jury verdict, death sentence. He could have chosen this approach simply because he knew no law and didn’t care to learn any, or because it was suggested to him from seeing Pièges. We’ll never know.

Pièges was released in France late in 1939, apparently just before the outbreak of World War II. Was it ever released in the U.S.? Yes it was. In the chapter on Siodmak in his 1994 book Beyond Hollywood’s Grasp: American Filmmakers Abroad, 1914-1945, Harry Waldman tells us that its original English-language title was Personal Column and quotes from the review of it that appeared in the New York Times. Clearly Woolrich could have seen the picture.

But did he? Since there’s no reason to believe he knew French, it’s unlikely he would have gone unless the print shown in New York was subtitled. Was it? Waldman doesn’t tell us and so far I haven’t found the answer elsewhere.

Siodmak is included in Beyond Hollywood’s Grasp because Harry Waldman believed he was American by birth. In fact, as I mentioned last month, the director was of German Jewish descent and his birthplace was Dresden. But the myth that he was a son of the South, born in Memphis, has circulated for generations. I must say I’m grateful that Harry Waldman accepted that myth. His mistake made my research for this month’s column ridiculously easy.

In my high school and college days I read just about all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels — except those that hadn’t been published yet! — and some but not all of the novels about Bertha Cool and Donald Lam that he wrote as A.A. Fair.

Last month I pulled out one that as far as I could remember I hadn’t read before and gave it a try. The results are mixed. Bedrooms Have Windows (1949) opens in the lobby of a large hotel to which, as we learn later, Lam has trailed a suspected con man. Suddenly a petite and gorgeous blonde, clearly meant to evoke Veronica Lake, invites Donald to escort her into the hotel’s cocktail lounge.

There she spins a yarn that takes them both to a remote motel where they register as husband and wife. The woman walks out on Lam around the same time that a man in another unit of the motel apparently kills his mistress and then himself. All this in the first couple of chapters!

Eventually we learn that the counter-plotting stems from the blonde’s determination to break up the marriage between the man her sister loves and the tramp he actually married and a blackmail ring’s determination to cash in on the situation. But, if I may mangle metaphors, under scrutiny much of the plot labyrinth collapses like a house of cards, which is an all too common fault in Gardner.

The coincidences that keep things moving might have fazed a Harry Stephen Keeler, and the storyline suffers from a number of coffee-out-the-nose elements, for example that the police accept as an obvious suicide the death of that guy in the motel who, as Gardner omits to tell us till near the end of the book, was shot between the eyes.

I wouldn’t rank this as one of the finest in the Cool and Lam series, but it moves fast and has plenty of the adversarial dialogue that was a Gardner trademark and reflects its time well, with plenty of references to the skyrocketing inflation of the years right after World War II. I don’t recommend it strongly but I can’t call it worthless either. Shall we say one thumb down?

This month’s column is both shorter and later than usual. Why? Because I have been and still am putting in a slew of hours on the index to Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection. Gad, what drudgery! The book will come out around February and a short excerpt will appear in the January 2013 EQMM. I hope those who read this column regularly will keep an eye out for both.

Sat 8 Sep 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I happened to be in New Jersey during the week in the middle of last month when an event took place in Manhattan which, had I known about it, would have led me to cross the Hudson and attend, and maybe get asked questions I couldn’t have answered on the spot.

On Thursday, August 16, as part of its ongoing series of French crime thrillers, the Museum of Modern Art ran the little-known 1939 film Pièges (Traps), starring Maurice Chevalier and directed by Robert Siodmak (1900-1973). Born in Dresden to Jewish parents, Siodmak wisely left Germany for France soon after Hitler came to power and, after completing Pièges, left France for a new life in Hollywood as a specialist in what became known as film noir.

Our interest here is in the skein of connections between Pièges, its director, and the most powerful of all noir authors, Cornell Woolrich.

First, the film’s springboard situation. After several young Parisian women mysteriously disappear, the police suspect that their adversary is a serial killer who finds his prey by placing newspaper ads seeking single young women. The cop in charge of the cases enlists the lovely taxi-dancer who roomed with the latest victim to go undercover, answer some of those ads, and serve as bait for a trap.

Sound familiar? To my ears the echoes of Woolrich’s pulp classic “Dime a Dance†(Black Mask, February 1938; first collected in The Dancing Detective, 1946, as by William Irish) are as loud as the roar of the sea, although to the best of my knowledge no one has commented upon the resemblance in print or on the Web.

Introducing Pièges to the MoMA audience, curator Laurence Kardish mentioned that the print, with new English subtitles, had arrived from France just two hours earlier. If the film had ever been shown in the U.S. before, it came and went in a blink.

Among the huge audience listening to Kardish was noir connoisseur Kurt Brokaw, who in an email (not to me) described “the first meandering hour†of the film as “more florid melodrama than noir… Chevalier sings and mugs and mopes around and is such a pain. The femme Marie Dea is good, but the picture seems to run forever.â€

Eventually, Brokaw pointed out, the film assumes a noir look and feel — and takes on a strong resemblance to Woolrich’s classic suspense novel Phantom Lady.

The problem here, as most Woolrich lovers know, is that that novel first appeared in hardcover in 1942, three years after Pièges. As they say in the cafés of Montmartre, was ist hier los? Could Woolrich have lifted Phantom Lady’s plot from a French film that had lifted its springboard situation from a Woolrich story?

When Brokaw’s correspondent invited me to weigh in on the issue, I replied that the original version of Phantom Lady was Woolrich’s short novel “Those Who Kill†(Detective Fiction Weekly, March 4, 1939).

The pub date would make it seem more likely that Pièges borrowed from Woolrich than the opposite. And when you factor into the equation that “Those Who Kill†takes place in France–!

At this point our conversation was joined by West Coast noir maven Eddie Muller, who told us that the Pièges/Phantom Lady connection was not a new discovery but had been discussed by Deborah Alpi in her 1998 book on Siodmak.

According to Alpi, the French film was based on the trial and conviction of a young German intellectual named Eugen Weidmann, who had murdered several women traveling in France.

Time out for a sidebar. Weidmann was the last criminal in France to be publicly guillotined. The execution took place in 1939, the same year Siodmak made Pièges, the same year Woolrich wrote his classic “Men Must Die†(Black Mask, August 1939; usually reprinted as “Guillotineâ€), which is about a French criminal desperately trying to avoid his date with the headsman. Coincidence, or had Woolrich been reading about the beheading of Weidmann?

As if our skein weren’t tangled enough already, there is one final knot. When Phantom Lady was itself filmed, in 1944, would anyone care to guess who got the job directing the picture? Yes, it was Robert Siodmak.

However we interpret this sequence of events, we seem to be stuck with some coincidences worthy of Woolrich himself, and maybe even of Harry Stephen Keeler. Someday I’ll track down Alpi’s book, and also a DVD of Pièges if there is one.

Anyone who sampled Boston Blackie on YouTube after reading my last column doesn’t need to be told that it was hardly a detective program at all but much more like an action-packed Western series set in the present, i.e. the early 1950s.

Also accessible on YouTube is another series of the same vintage which is closer to the detective genre and even features reasoning of sorts, but I didn’t care for it 60 years ago and still don’t today.

The 39-episode Front Page Detective was produced by small-screen pioneer Jerry Fairbanks (1904-1995), first broadcast on the short-lived Dumont network in 1951 and rerun times without number on local stations throughout the rest of the Fifties.

The title came from a pulp true-crime magazine but its protagonist, café-society columnist and amateur detective David Chase — described as a sleuth with “an eye for the ladies, a nose for news, and a sixth sense for danger†— was created especially for TV.

“Presenting an unusual story of love and mystery!†the unseen announcer would purr in dulcet tones at the start of each episode. His introduction concluded with: “And now for another thrilling adventure as we accompany David Chase and watch him match wits with those who would take the law into their own hands.â€

Starring as Chase was one-time matinee idol Edmund Lowe (1892-1971), a name familiar to moviegoers for a third of a century before his entry into television. During the 1920s he specialized in suave romantic roles complete with waxed mustache, but the biggest boost in his film career came when director Raoul Walsh cast him opposite Victor McLaglen in What Price Glory? (Fox, 1926), first of the Captain Flagg-Sergeant Quirt military comedies.

Lowe’s foremost contribution to the detective film came ten years later when he portrayed Philo Vance in The Garden Murder Case (MGM, 1936), but he also played a New York plainclothesman of the 1890s opposite Mae West in Every Day’s a Holiday (Paramount, 1938).

By the early 1950s Lowe had begun to show his age, and in Front Page Detective he looked all too convincingly like a man of almost sixty who’s determined to pass himself off as 25 years younger.

In many an episode he’d romance the woman in the case, rattle off a few deductions — once he reasoned that a letter supposedly from an Englishwoman was a forgery because the writer used the U.S. spelling “check†rather than the British “cheque†— and then collar the villain personally after a pistol battle or fistfight underscored by Lee Zahler’s background music for Mascot and early Republic serials.

Supporting Lowe were Paula Drew as Chase’s fashion-designer girlfriend and crusty George Pembroke as the inevitable stupid cop. Appearing in individual episodes were such stalwarts of TV’s pioneer days as Joe Besser, Rand Brooks, Maurice Cass, Jorja Curtright, Jonathan Hale, Frank Jenks and Lyle Talbot.

Filming was 99% indoors, on some of the cheapest sets ever seen by the televiewer’s eye. The director of every episode I’ve seen recently was Arnold Wester, whose name crops up almost nowhere else in TV history, hinting that it may have been an alias for producer Jerry Fairbanks.

Whoever he was, his idea of directing was to point the camera at the actors and leave the room. Many scripts were by veterans of pulp detective magazines and radio like Robert Leslie Bellem and Irvin Ashkenazy, with an occasional contribution by Curt Siodmak, the younger brother of director Robert Siodmak — do I connect the items in this column or what? — and author of the classic horror novel Donovan’s Brain.

Three episodes of the series — “Murder Rides the Night Train,†“Seven Seas to Danger†and “Alibi for Suicide†— are accessible on YouTube, and a few others can be found on various DVD sets in the bins of dollar stores.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYPaS6qp3-A

Most seem to have vanished but their gimmicks can often be deduced from the brief descriptions in crumbling issues of TV Guide. In “The Case of the Perfect Secretary†Chase tries to find out why Dr. Owens, the inventor of a synthetic cortisone, didn’t show up for a scheduled lecture. He finds Owens’ laboratory deserted and later discovers that the doctor has been murdered, the letter M imprinted on his forehead. It takes no Charlie Chan to figure out that the M is most likely a W.

“Honey for Your Tea†finds Chase looking into the claim of a young actress that her fiancé was brutally murdered by her dramatic coach (Maurice Cass), a gnarled and crippled old man whose hobby is beekeeping. Anyone want to bet that this isn’t the old bee-venom poisoning shtick?

In “The Other Face†Chase investigates the death of a handsome actor who “accidentally†fell from his penthouse terrace shortly after telling his psychiatrist of his desire to fall through space. If the murder victim didn’t turn out to be not the actor but his look-alike understudy, toads fly.

Other episodes seem to have more intriguing story lines. In “Napoleon’s Obituary†a man named for Bonaparte dies the day after asking Chase to write his obituary, and the trail leads our sleuth to a house all of whose inhabitants sport the names of historic figures.

In “Ringside Seat for Murder†Chase witnesses a bizarre murder during a wrestling match where one of the athletes (using the term loosely) is stabbed in the back with a poisoned dart while pinned to the mat by his opponent.

Front Page Detective never pretended to be a classic, but for all its cliches and Grade ZZZ production values it was a pioneering effort in tele-detection that deserves perhaps a wee bit more than to be totally forgotten.

Fri 13 Jul 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

It’s official, gang. I’ve just signed a contract with Perfect Crime Books for the publication of — how shall I describe it? It may not be quite as hefty as my book on Cornell Woolrich, whose title I adapted for the titles of these columns, but it will certainly qualify as a literary doorstop.

Back in the 1980s I wanted my Woolrich book to answer almost any imaginable question about the haunted recluse I’ve called the Hitchcock of the written word. Now as I slipslide into senility I want my new book to be just as comprehensive about the two first cousins from Brooklyn who wrote some of the most complex and involuted detective novels of the genre’s golden age.

Are you familiar with everything bagels? This tome will be, I hope, the Everything Book on Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Its tentative title is Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection.

I think I heard a question from cyberspace. “Hey, didn’t you do that book already, back in the Watergate era?†Well, sort of. But as I got older I became convinced that I hadn’t done all that good a job.

Fred Dannay was the public face of Ellery Queen, and in the years after we met he became the closest to a grandfather I’ve ever known, but I never really got to know the much more private Manny Lee. He and I had exchanged a few letters, and we met briefly at the Edgars dinner in 1970, but he died before we could meet again.

Because of his untimely death Royal Bloodline inadvertently gave the impression that “Ellery Queen†meant 90% Fred Dannay. One of the most important items on my personal bucket list was to do justice to Manny.

Thanks largely to the memoirs published by his son Rand Lee, and to the Dannay-Lee correspondence (in Blood Relations, published early this year by the same Perfect Crime Books that will issue The Art of Detection), and to the correspondence between Manny and Anthony Boucher, which is archived at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, I’ve come to a much clearer understanding of Manny, of who he was and how he lived and worked and thought.

The Art of Detection improves on Royal Bloodline in all sorts of ways but for me this one is the most important. In addition it provides much more detail on subjects like the EQ radio series (1939-48) and the decades-long interaction between the cousins and Boucher.

And of course it covers all sorts of subjects that postdate the early 1970s, like the EQ TV series with Jim Hutton, and Fred’s third marriage and last years and death. And there will be a number of photographs never seen before.

When I first discovered the Ellery Queen novels, that byline was a household name. It still was when I first met Fred Dannay. I can’t believe that in my lifetime the Queen name has (except in Japan) been so completely forgotten. Maybe, just maybe, with the publication of Blood Relations this year, and of my book next year, and of Jeffrey Marks’ biography-in-progress two or three years from now, I’ll live to see the return of Ellery Queen to the public eye.

On June 5, at age 91, Ray Bradbury died. In his own field he was and will remain a giant. As far as I can determine, among the hundreds of authors whose work Anthony Boucher reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle during and for a while after World War II, he was the last one standing.

Reviewing Bradbury’s Dark Carnival collection in his Chronicle column for June 22, 1947, Boucher called the author “the most fascinating and individual talent to appear in the fantasy field for a long time….[T]here’s no telling what may come of this still very young man.â€

During his early and middle twenties Bradbury also wrote stories for crime pulps like New Detective, Dime Mystery and Detective Tales. Was Boucher familiar with them?

“For years,†he wrote in his Dark Carnival review, “I have been prowling newsstands and buying any magazine with a Ray Bradbury story.†Observe that that sentence isn’t limited to fantasy-horror magazines.

In any event Boucher was long dead by the time Bradbury’s earliest crime tales were collected in the paperback original A Memory of Murder (Dell, 1984). We know that Bradbury was a great admirer of Cornell Woolrich, and he may well have been the first writer for whose short crime fiction Woolrich was the model and polestar.

Woolrich never once used a series character. After two tales about a character called the Douser — for my money the weakest of the fifteen in the collection — Bradbury followed that lead. He never approached Woolrich’s mastery of pure edge-of-the-chair suspense but, for a kid in his middle twenties, did a noble job creating noir atmosphere Woolrich style.

The more you’re at home in Woolrich, the more you feel a sense of deja vu when you read Bradbury’s stories. “Yesterday I Lived!†(Flynn’s Detective Fiction, August 1944) echoes Woolrich’s “Preview of Death†(Dime Detective, November 15, 1934; collected in Darkness at Dawn, 1985) in the sense that both are about a Hollywood plainclothesman of low rank investigating the death of a lovely actress while she’s filming a scene:

“He went out into the rain. It beat cold on him… Cleve clenched his jaw and looked straight up at the sky and let the night cry on him, all over him, soaking him through and through; in perfect harmony, the night and he and the crying dark.â€

In that paragraph and countless others in these stories, it’s obvious whom Bradbury is channeling.

Sometimes Bradbury offers his own take on a Woolrich springboard situation, for example in “It Burns Me Up!†(Dime Mystery, November 1944), which tracks Woolrich’s “If the Dead Could Talk†(Black Mask, February 1943; collected in Dead Man’s Blues, 1947) in that each is narrated in first person by a corpse.

Sometimes there’s an echo even in the titles, for example “Wake for the Living†(Dime Mystery, September 1947), which evokes Woolrich’s classic “Graves for the Living†(Dime Mystery, June 1937; collected in Nightwebs, 1971).

Bradbury’s prose tends to be more shrill and lurid than Woolrich’s, and pockmarked with exclamation points — even in the titles! — as Woolrich’s never was, but the influence is crystal clear.

In his introduction to A Memory of Murder, Bradbury was quite modest about his contribution to our genre:

“I floundered, I thrashed, sometimes I lost, sometimes I won. But I was trying … I hope you will judge kindly, and let me off easy.â€

This old jurist has done just that, and urges others who reread these stories to bang their gavels softly.

“Sweet, dear, impossible man. I wonder who he’s making love to now. I wish it were me. I have the education and breeding to appreciate a gentleman like he is.â€

No one seems to have guessed who wrote those ludicrous lines, supposedly from the viewpoint of an educated woman, that I quoted in my last column.

Maybe that’s because in a sense I was trying to mislead. The malapropisms from Keeler, Avallone, John Ball, William Ard and myself were false clues in the Carr-Christie-Queen manner, playing completely fair with the reader but designed to give the impression that the sixth quotation was by a sixth person.

In fact it wasn’t. The perp, as at least one reader should have figured out, was the ineffable Avallone. Here’s another from the same inexhaustible cornucopia:

“Wolfman Dakota, born of an Apache mother and a Texan rancher, with bronze skin and hot blood in his veins … killed with a weapon unique in crime-land circles. A blowgun filled with poison-tipped darts. A leftover from his Apache heritage….â€

Ah yes, who can forget the climax of Stagecoach, with those damn red savages chasing the coach across the salt flats, blowing their poison darts at the Duke and Claire Trevor and all the other passengers?

Thu 1 Dec 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME, by Marvin Lachman

LAWRENCE BLOCK – Deadly Honeymoon. Macmillan, hardcover, 1967. Paperback reprints include: Dell, 1969; Jove, 1986; Carroll & Graf, 1995. Filmed as Nightmare Honeymoon (1974).

Transplant Cornell Woolrich into a more permissive decade, and you would have this book, first published in hardcover in 1967.

A young attorney and his bride go to a remote Pennsylvania cabin for; their honeymoon, but it is interrupted by rape and murder. In this brutal but extremely suspenseful novel, a manhunt is generated by a desire for revenge with which the reader can easily identify.

ANNE CHAMBERLAIN -The Tall Dark Man. Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1955. Paperback reprints include: Dell #925, 1956; Avon Classic Crime PN322, 1970; Academy Chicago, 1986.

The plot of this 1955 mystery, reprinted in an especially attractive edition, is decidedly Woolrichian. A thirteen year-old girl says she has seen a murder through the window of her Ohio school room, but no one will believe her. She also claims that the murderer saw and recognized her.

When Anthony Boucher originally reviewed this book, he paid it the extravagant praise of saying “This is purely and absolutely, The Suspense Novel, in an ideal form, which the genre rarely attains.” He did not exaggerate very much.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 8, No. 4, July-Aug 1986.

Wed 15 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

SUSPENSE — WITH A HITCH

Cornell Woolrich’s Rear Window and Other Stories

A Review by Curt J. Evans

CORNELL WOOLRICH – Rear Window and Other Stories. Penguin, paperback, 1994. First published as Rear Window and Four Short Novels: Ballantine, paperback original, 1984.

There have been so many Cornell Woolrich short story collections collected over the years that one can enter into an agonizing state of suspense just trying to decide which of these collections to buy. Fortunately I can assure you — if you do not know it already — that this particular collection is a corker.

Interestingly, not only is the title short story (“Rear Window,†1942) associated with that cinematic master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, so are the collection’s additional four tales: “Post-Mortem†(1940), “Three O’Clock†(1938), “Change of Murder†(1936) and “Momentum†(1940). Indeed, I strongly suspect this is why they are collected here in this volume.

Rear Window of course, is one of Hitchcock’s great films, while “Post-Mortem,†“Change of Murder†and “Momentum†all were filmed for the memorable television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents (“Change of Murder†as “the Big Switchâ€) and “Three O’Clock†was directed by Hitchcock himself for the fifties television series Suspicion.

I have seen all of these adaptations bar “Three O’Clock†and all are first class mystery entertainment. (“Three O’Clock†was retitled “Four O’Clock” and shown as the first episode of Suspicion on 30 September 1957. I have never seen an episode of this series.)

Woolrich’s “Rear Window†is an excellent story, but for me it has been rather upstaged by the film. Not so the rest, however. Of the remaining four stories the most minor is the early Woolrich tale “Change of Murder,†though it a clever little piece with a nice twist in the tail (it also is the shortest of the five by far).

“Momentum†is a strong work (again with a fine twist), but my absolute favorites in this collection are “Post-Mortem†and “Three O’Clock.†Though I have great admiration for the droll television adaptation of the former (with its excellent performances by Joanna Moore, Tatum O’Neal’s mother, and Steve Forrest, a brother of Dana Andrews), I found the story easily stands on its own as a biting and ironic domestic suspense classic rather on the order of Dorothy L. Sayers’ brilliant “Suspicion.†Quite a bit of plot complexity is packed into this tale (which was streamlined in the adaptation).

As indicated above, “Three O’Clock†was completely new to me, and I found it a powerful screw turner of tension. Again the tale has a domestic setting, but where “Post-Mortem†is black comedy, “Three O’Clock†is just blackly grim — and powerfully and memorably so.

Suspense is remorselessly (if at times improbably) drawn out and the twist, when it came, took me totally by surprise. I hesitate to say anything in detail about the plot for those who have not read the tale or seen the television adaptation. To those people: just read it!

Rear Window and Other Stories seems to me a great place to start a literary relationship with the great master of suspense Cornell Woolrich. It is also one to return to again and again … if you dare. Unpleasant dreams!

Tue 22 Jun 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Of all the authors who in the years after World War II moved mystery fiction “from the detective story to the crime novel,” perhaps the most influential American woman was Patricia Highsmith (1921-1995).

Certainly she’s the only one to have received so much critical attention after her death: first Andrew Wilson’s biography in 2003, more recently Joan Schenkar’s The Talented Miss Highsmith, which isn’t a conventional biography but more an exploration of Highsmith’s obsession-torn mind and emotions and how they spilled over into novels like Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley.

If you think Cornell Woolrich was something of a psychopath and a creep, you don’t know the meaning of those words till you’ve encountered Highsmith.

Both, of course, were homosexual. I gather from Schenkar’s book that Highsmith, who was born in Texas and came of age in the feverish New York of the World War II years and went through lovers with the fury of a Texas twister, was never terribly comfortable with being a lesbian.

Woolrich was perhaps the most deeply closeted, self-hating homosexual male author that ever lived. Both wound up worth several million but often acted as if they were penniless. Both lived mainly on booze, cigarettes and coffee, with peanut butter added to the diet in Highsmith’s case.

Both bequeathed their copyrights and other property to institutions, not human beings. Woolrich left an autobiographical manuscript (Blues of a Lifetime) which is full of obvious fiction; Highsmith left 8000 pages of notebooks which, as Shenkar demonstrates, are also pockmarked with falsifications.

But there were notable differences too. Just to mention one, Highsmith was fixated on possessions, keeping everything (except any paper trail leading back to the seven years she had spent in her twenties writing scripts for comic books like Spy Smasher and Jap Buster Johnson), while Woolrich kept nothing, not even copies of his novels and stories.

It’s most unlikely that the two ever met. Woolrich read very little crime fiction but appeared regularly in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in the Fifties and Sixties and may have read Highsmith’s EQMM stories.

We know she read the magazine steadily and, in her book Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, devoted almost a full page to Woolrich’s “Murder After Death” (EQMM, December 1964).

Why did she single out this rarely reprinted and never collected tale? Perhaps she saw something akin to her own evil protagonists in Georg Mohler, a loser at the game of love who turns to crime for emotional revenge.

When the wealthy and lovely Delphine rejects him for law student Reed Holcomb and then dies a sudden but natural death, Mohler concocts a laughably dumb plot to sneak into the funeral parlor, inject poison into her body and frame Holcomb for murder.

Woolrich’s detail work is sloppy and implausible and his climactic twist, like those in several of his earlier stories, comes straight out of James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. But the scene where Mohler hides in the funeral home and posthumously poisons his lover’s corpse is a gem of poetic horror.

If any single element in the tale deserved Highsmith’s attention it was this one. In fact she spent most of the page summarizing the plot, calling it a “quite well-done gimmick story” with “an elaborate but quite entertaining and believable scaffolding….” Go figure.

It was a gimmick—the two men in Strangers on a Train (1950) agreeing (or did they?) to exchange murders — that first made crime fiction readers (not to mention Alfred Hitchcock) take notice of the not yet 30-year-old Highsmith.

Later authors including Nicholas Blake and Fredric Brown worked their own variations on the theme. But who remembers its first appearance in the genre?

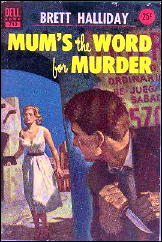

Mum’s the Word for Murder (1938) uses very much the same gimmick, although here it involves three murders, not two, and is saved till the solution rather than employed as a springboard.

The byline on this long-forgotten book was Asa Baker but the author’s real name was Davis Dresser and his best-known pseudonym was Brett Halliday, which he used for the all but endless adventures of Miami PI Michael Shayne, beginning in 1939, a year after Mum’s the Word came out.

As chance would have it, much of both novels is set in Texas, where both Dresser and Highsmith spent several of their formative years.

Thu 20 May 2010

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

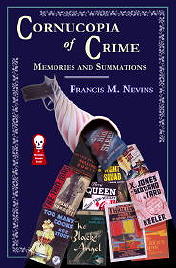

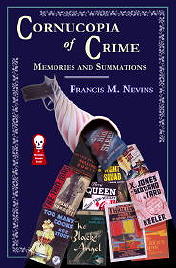

My apologies for the delay between columns. I was on the road for two and a half weeks, when I wasn’t traveling, proofreading my next book took up all my writing time.

Cornucopia of Crime, which Ramble House will be doing, will probably run about 450 closely printed pages when the index is finished. It will bring together a ton of long and short pieces I’ve written about mystery writers over the past 40-odd years, including some bits from this column.

The cover is by New Zealander Gavin O’Keefe, and as anyone can see from the attached image, it’s a knockout.

Part of my recent week in New York I spent at Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where Fred Dannay’s papers are archived, looking into whether Fred had saved anything written to him by Cornell Woolrich that I wasn’t already aware of.

My most interesting find was a brief undated note that accompanied Woolrich’s last story.”Just consider it on its merits, like you always have all stories,” he wrote. “Don’t feel sorry; I’ve had it better than most guys. I’d like one last publication, before I kiss it off. I’m a writer to the end. And glad I was one.”

Clearly the story accompanying this note was “New York Blues,” which Fred purchased in May or June of 1967 but didn’t publish in EQMM until the December 1970 issue, more than two years after Woolrich’s death.

There’s a penciled note on Woolrich’s covering letter which looks to me like Fred’s handwriting and suggests an alternate title for the story, one I actually like more than Woolrich’s: “The Last Hours.”

In the end, of course, Fred went with Woolrich’s title.

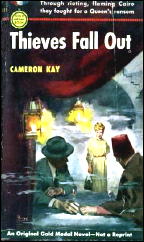

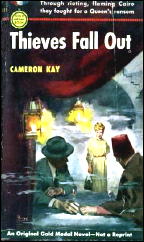

Stopping off in Cincinnati on the way home from my little odyssey, I happened upon a nice copy of Thieves Fall Out (Gold Medal pb #311, 1953), an obscure paperback original bearing the byline of Cameron Kay, which has never been seen on any other book before or since.

The true author? Gore Vidal. It’s an ordinary little number, set in Egypt in the days of King Farouk, with minimal action or suspense and not a bit of the satiric wit that enlivened the three whodunits Vidal wrote as Edgar Box during the same time period.

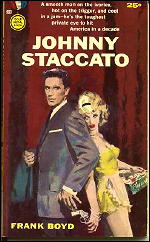

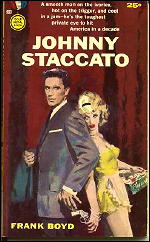

Among all the TV private eye series of the Fifties and Sixties that never caught on and were quickly cancelled, perhaps the finest was Johnny Staccato (NBC, 1959-60), starring John Cassavetes as a jazz pianist who makes ends meet by working as an apparently unlicensed PI.

Even in my late teens the music of my life was classical music, but I was still very fond of this series in first run and watched it from the first episode to the 27th and last.

Half a century later I’ve found the complete series on DVD and it’s still first-rate: evocative streets-of-New-York photography, fine performances (guests included Michael Landon, Martin Landau, Gena Rowlands, Elizabeth Montgomery, Elisha Cook and Mary Tyler Moore), excellent direction (with five episodes helmed by Cassavetes himself), offbeat scripts (including some by Fifties PI novelist Henry Kane), and of course tons of jazz, with a young hepcat then known as Johnny and later as John Williams—like yeah, man, that John Williams— doing the honors on piano.

The series must have been planned as a sort of Peter Gunn clone but turned out quite different, mainly, I think, because the cool-jazz sound of Gunn was replaced by a hotter, more passionate music style.

Something I read recently (I won’t say where) suggested to me that there ought to be an annual award for most eye-popping boner in or about mystery fiction. My first candidate for this honor, who shall remain nameless, wrote of Nero Wolfe that he “tended a rose garden on his roof….”

Ouch! That’s a thorn from one of those roses.

Sun 25 Oct 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

CORNELL WOOLRICH – The Bride Wore Black. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft, including: Pocket #271, 2nd printing 1945; Pyramid #80, 1953, as Beware the Lady; Dell D186, 1957, Great Mystery Library #1; Ace G-699; Collier, 1964; Raven House, 1981; Ballantine, July 1984.

Film: Films du Carosse, 1968, as La mariée était en noir (The Bride Wore Black). Co-screenwriter & director: Francois Truffaut.

The Bride Wore Black is Cornell Woolich’s first novel and has been reprinted by about half a dozen different paperback houses. If you’ve never read Woolrich, it is a splendid introduction and [when this review was first written] a recent edition from Ballantine may still be available.

While it is not Woolrich at his very best (for that, you’d have to read pulp novelets like “Goodbye, New York” or later books like Rendezvous in Black, also reprinted by Ballantine), it is very good indeed.

Woolrich is best known for his heart-stopping suspense, emotional prose, and use of outrageous coincidences. In The Bride Wore Black, we have his usual narrative drive, but the language is a bit more objective than it sometimes is, and the result is a bit less reader involvement than is needed.

The coincidences are there, in spades, and that makes suspending disbelief a bit tougher than usual. Still, only someone who’s read the best Woolrich would dare to cavil at this book, so don’t miss it if you’ve never read it.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 3, May/June 1987

(very slightly revised).

Editorial Comment: As soon as I’m able, I’ll be posting the three reviews of Woolrich novels that Mike Nevins did for 1001 Midnights, one a day, perhaps, beginning tomorrow. The three: The Bride Wore Black, The Black Curtain, and The Black Angel.

Wed 22 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Francis M. Nevins:

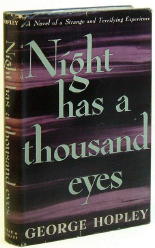

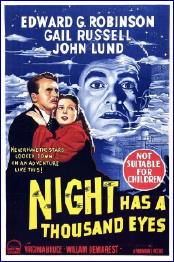

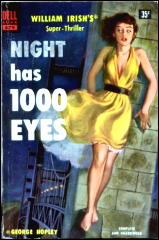

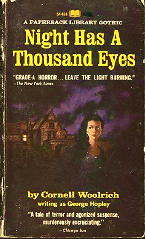

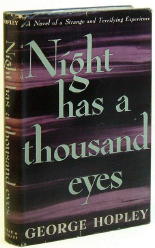

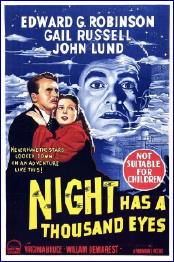

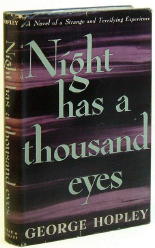

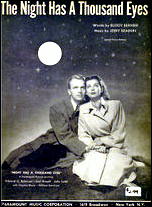

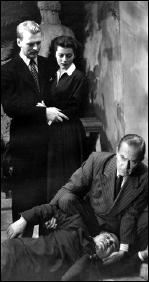

GEORGE HOPLEY – Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Reprinted as by William Irish: Dell #679, 1953. Reprinted as by Cornell Woolrich: Paperback Library 54-438, 1967. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was the first of two novels published under a pseudonym made up of Cornell Woolrich’s middle names, and of all his books it’s the one most completely dominated by death and fate. A simpleminded recluse with apparently uncanny powers predicts that millionaire Harlan Reid will die in three weeks, precisely at midnight, at the jaws of a lion.

The tension rises to an unbearable pitch as the apparently doomed man, his daughter, and a sympathetic young homicide detective struggle to avert a destiny that they at first suspect and soon come to hope was conceived by a merely human power.

Woolrich makes us live the emotional torment and suspense of the situation until we are literally shivering in our seats.

The roots of Woolrich’ s longest and perhaps finest novel lie deep in his past. From the moment at the age of eleven when he knew that someday he would have to die, he “had that trapped feeling,” he wrote in his unpublished autobiography, “like some sort of a poor insect that you’ve put inside a down-turned glass, and it tries to climb up the sides, and it can’t, and it can’t, and it can’t.”

Of all the recurring nightmare situations in his noir repertory, the most terrifying is that of the person doomed to die at a precise moment, and knowing what that moment is, and flailing out desperately against his or her fate.

This is what connects the protagonists of Woolrich’ s strongest work, including Paul Stapp in “Three O’Clock,” Robert Lamont in “Guillotine,” Scott Henderson in Phantom Lady, and of course Reid in Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Only a writer tom apart by human mortality could have created these stories.

Published under a new by-line and by a firm never before associated with Woolrich, Night Has a Thousand Eyes seems to have been intended as a breakthrough book, to introduce the author to a wider audience, but it was too grim and unsettling for huge commercial success.

The 1948 movie version, starring Edward G. Robinson as a carnival mind reader with the power to foresee disasters, had almost nothing in common with the story line of Woolrich’ s novel, let alone its power and terror.

This book is what noir literature is all about, a nerve-shredding suspense classic of the highest quality and a work that once read can never be forgotten.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Wed 22 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

GEORGE HOPLEY – Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Reprinted as by William Irish: Dell #679, 1953. Reprinted as by Cornell Woolrich: Paperback Library 54-438, 1967. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

Cornell Woolrich, that twisted and tortured man who haunted the novel of suspense like some Twentieth Century Poe, coined the term “line of suspense” to describe the mechanism that drives a good suspense novel.

In the simplest terms it is the element that drives the tale from one incident to the next — perhaps the killer’s motive as in The Bride Wore Black, the heroes amnesia as in Black Curtain, or here, in Woolrich’s masterpiece, the possibility of psychic powers and the inevitability of fate.

Woolrich’s novels are haunted by fate, sheer blind cruel and pointless fate. An unmarried pregnant woman on a train survives an accident and happens to be mistaken for another pregnant woman in the same car whose husband’s wealthy family has never seen her; a night’s drunk finds you facing the hot seat with no memory of what happened; a leopard escaped from an night club act cloaks the twisted mind of a killer; a sailor and a taxi dancer have only until dawn to clear him of a crime…

Fate is always having its little joke in Woolrich’s novels and stories, and in Night Has 1000 Eyes that little joke is at its most effective, and terrible.

Night opens appropriately at night. The hero is a young detective who spots an attractive young woman attempting suicide. He stops her, only to find she is desperate and frightened out of her wits.

Her wealthy father has been threatened, but this is no ordinary threat. A man claiming psychic powers has told her that her father will die at an appointed time and cannot be saved. And this psychic is never wrong.

Never.

Naturally the police take a dim view of this sort of thing, even though the psychic seemingly has asked for no money and committed no crime. But they encounter clever bunco artists all the time and they know that if they look deep enough they’ll find the game behind this one. Besides you can’t go around threatening a cities most wealthy men with blind retribution — it makes the taxpayers nervous.

Meanwhile the clock ticks and the time nears when the appointed hour will come.

And for every step forward there is one back, and still the uncanny predictions of this strange man come true.

When they finally uncover a tawdry romantic triangle involving the psychic, the victim, and the girl’s late mother they are certain they have the key — revenge and extortion. Still, they take no chances. They ring the victim with police and arrest the psychic who insists he means no harm to his old friend, and that he too will die shortly after the first man at his own appointed hour.

Now Woolrich ratchets the horror up to incredible levels. The tension is palpable and the suspense grows as each twist, each revelation comes. The psychic has predicted the man will die between the paws of a lion, and as the hour nears a lion escapes from the zoo, loose in the very area where the victim lives.

Mere coincidence, and yet …

And yet.

Ernest K. Gann coined the term “fate is the hunter” to explain why he left commercial aviation — because at some point in a pilot’s career the laws of simple math catch up with him and it becomes more likely he will crash than that he won’t. Woolrich understood the idea. Fate is a remorseless hunter, but Woolrich knows too you can’t run or hide.

Night Has a Thosand Eyes is a suspense novel and not a horror novel, but rightly has been claimed by both genres because the effect of the accumulation of events and coincidence begins to resemble something supernatural, though at each and every turn Woolrich is careful to eschew the simple explanation.

Again and again he takes the reader right up to the point of madness, and then pulls away, reveals another twist, shows us another possible path, all the while maintaining a palpable line of suspense that is almost unbearable.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a fairly long novel, but I have a hard time believing anyone once starting it put it down before it ended. Or slept much afterward.

And that may be where this book most resembles a horror novel and not a suspense novel, because most good suspense novels let you go when they come to the end. There is a build up to incredible tension and then a release.

Not in Night Has a Thousand Eyes.

If anything this book is more disturbing when it is over.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was well filmed by John Farrow with a fine screenplay by Barré Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer, with Gail Russell perfectly cast as the fey girl, John Lund the hero, Edward G, Robinson the psychic, William Demarest a doubting cop, and Jerome Cowan the doomed victim.

It’s a fine piece of film noir, but it is only a pale shadow of the novel. I don’t know that you could translate on film the tension that Woolrich builds in print. I’m not sure you’d want to, because as I say, Night Has a Thousand Eyes doesn’t let you off the hook. Not even when you have turned the last page and laid the book aside.

The book also inspired a popular song that warned us “The night has a thousand eyes/ and a thousand eyes can’t help but see…” recorded by Bobbie Vee, and the song from the film by John Brahin was and still is a popular jazz riff. (Follow the link to a YouTube video of the Bobby Vee version.)

That title has the ring of some ancient bit of wisdom or poetry. It has the feel of found wisdom, of something we all knew, but never put into words before this.

The night has one thousand eyes and they are watching us. We cannot run from them, we cannot escape them. Fate will not be denied, nor can any man escape his appointed time. We all will make our own appointment in Samara on time.

And perhaps it is that inevitability that gives this novel its power. We aren’t let off with easy answers, and though the solution leaves itself fully open for rational explanation there is a cold dark corner of the soul that knows that isn’t what Woolrich was telling us.

Woolrich wrote only one other as George Hopley, the majority of his work appearing as by Woolrich or William Irish. Many of his novels deserve to be read and reread, they are masterpieces of suspense, and despite his tendency to overheated prose even the least of them are worth rereading. But Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a special case.

Even among his output of taut and often disturbing novels, this one is a masterpiece. This is the one unforgettable novel in his repertoire.

Read it and you will never forget it.

But don’t read it before bedtime.

Not if you ever want a good night’s sleep again.