Reviewed by TONY BAER:

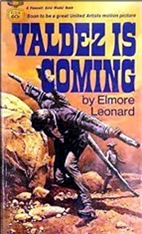

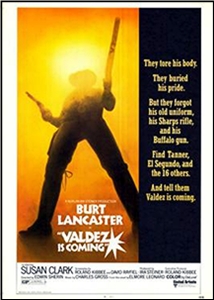

ELMORE LEONARD – Valdez Is Coming. Fawcett R2328, paperback original, October 1970. Library of America #308, hardcover: Elmore Leonard: Westerns: Last Stand at Saber River / Hombre / Valdez Is Coming / Forty Lashes Less One / Stories. Film: United Artists, 1971, starring Burt Lancaster & Susan Clark; director: Edwin Sherin.

Bob Valdez is a local constable in some bullshit Arizona corporation town, late 1800’s. There’s some trouble down at a barn.

Frank Tanner is the big man in town. He ain’t a big man physically. Tough and wiry as the expired slim jim between the seat folds of your rental car. But he’s got maybe 20 gunmen working for him, and he makes a lot of coin running guns down to Mexico to sell to the revolutionaries and running cattle thru the frontier.

Tanner says the man in the house is a black deserter of the cavalry who murdered Tanner’s friend. And this deserter has got to die. So he and his gunmen have cornered the man inside a barn, and have been shooting the thing up, indiscriminately.

Valdez, being the law, figures he’d better come around and see what the ruckus is. None of your business, he’s told. Brusquely. The law is expected to serve the Man.

Well I’m still gonna go in and talk to the guy, says Valdez.

So Valdez walks to the barn. Knocks on the door. And talks to the guy and his wife, a Native American woman. Very pregnant. The man has proof he’s not the guy they’re looking for. He was honorably discharged, and his papers are in his wagon.

They go to retrieve the papers, Valdez yells for Tanner to hold his fire. But Tanner has used Valdez as a diversion to set his rifle sights on his prey. At close range. The man now thinks Valdez has betrayed him. And draws his pistol.

Valdez, having no choice, pulls his double barreled sawed off scattershot first, and blows the man away.

Tanner walks up to the man and says: He’s not the guy. Black guys all look the same anyway. But this ain’t him. You killed the wrong guy.

Valdez says: It was you that made the mistake. You took the woman’s husband. You should pay her five hundred bucks for the loss of her husband, the baby’s father.

‘If I wanted you to talk, I’d tell you,’ says Tanner. Learn your place. And tells his men to kick Valdez’s ass. Strap a cross to his back. In the desert. So he can die.

Valdez doesn’t die, though. He kidnaps Tanner’s woman. A beautiful blonde. He’ll give her back, he says. Soon as Tanner pays the widow her $500.

Tanner’s woman “had come from Prescott with her nightgowns and linens to marry James C. Erin, and five years and six months later she fired three bullets into him from a service revolver and left him dead.â€

Once kidnapped by Valdez, turns out she’s not too fond of Tanner either. She likes Valdez better:

“Slowly her hands came up in front of her and she began unbuttoning her shirt, her hands working down gradually from her throat to her waist. She said, ‘I told you I killed my husband. I told you I don’t want to marry Frank Tanner. I told you I have nothing. You decide what I want.â€

Tanner tells his men kill Valdez and bring his woman back.

But when she tells his men she prefers Valdez, they turn on Tanner. “A man holds his woman or he doesn’t. It’s up to him, a personal thing between him and the man who took the woman.â€

Tanner took the Native woman’s man. So Valdez took Tanner’s woman.

Justice.

———–

It’s a good, tough Western. Some atypical stuff happens for a Western — not the least of which is the woman’s free will. She’s not your average damsel in distress. And this seems to take all sides by surprise. The ending, too, is atypical. At first I was a bit disappointed by a lack of fireworks. There’s a great buildup to a showdown that never happens.

But the more I think about it, the more I like it. Apparently the number of actual gunfights in the wild west were surprisingly few. Plenty of folks surely chickened out. But chickens are rarely the stuff of myth. And the western is nothing if not mythology. Elmore Leonard shows great courage in delivering a chicken shit denouement.

I enjoyed it. If Valdez is coming, you should go ahead and let him in. He’s good company.