May 2009

Monthly Archive

Sun 31 May 2009

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

A few weeks ago Turner Classic Movies presented yet another film of the Thirties which, had it been made in the Forties, would have been accepted by everyone as film noir.

I refer to Crime and Punishment (Columbia, 1935), based on Dostoevski’s classic novel. For obvious budgetary reasons director Josef von Sternberg makes no attempt to recreate mid-19th-century St. Petersburg, and we are told in an opening title that the story could take place at any time and anywhere.

This is why the protagonist’s name morphs from Rodion to Roderick Raskolnikov, and also why we never see any automobiles or horse-drawn vehicles or any other form of transportation that might give us a clue to whether we are in the 19th or the 20th century.

Amid grotesque shadows and bizarre camera angles, Peter Lorre in his first role after escaping from Hitler’s Europe played Raskolnikov — how could that whiny, sweaty, pop-eyed little toad have ever imagined himself to be an Ubermensch above the law? — while the police detective Porfiry Petrovich was played by Edward Arnold, who the following year would be cast, for one film only, as Nero Wolfe.

If you missed the TCM debut of this version of Crime and Punishment, watch for it when next it’s shown.

Speaking of Nero, it was my good fortune that I began reading Rex Stout in the late 1950s, when I was in my middle teens and also pigging out on a dozen or more TV Western series a week.

Why was this a lucky break for me? Because one of those Western series saved me from misunderstanding Archie Goodwin.

If you were following the Wolfe saga during the Hammett-Chandler era when the novels and novellas were first coming out, you might easily have tried to assimilate Archie to the legion of wisecracking PI/first person narrators of the time, and then rejected the character when you sensed what a poor fit that was.

Even so astute a critic as John Dickson Carr, writing in 1946, referred to Archie as “insufferable” and a “latter-day Buster Brown.”

But if you were fortunate enough to discover Stout in the late Fifties, at a time when millions of Americans including myself were watching Maverick every Sunday evening, you might have recognized Archie Goodwin and Bret Maverick as soul brothers.

You might have credited Rex Stout with having created in prose the Great American Wiseass prototype which James Garner brought to perfection on film. You might have longed to see one of Stout’s novels filmed with Orson Welles as Wolfe and Garner as Archie. At least I did. What a shame that it never happened!

When did TV movies begin? The first films that networks called by that name were broadcast in the fall of 1964. But if a TV movie is a feature-length film that tells a continuous story and was first seen in a single installment, the genre dates back at least to the suspense thrillers and Westerns that were aired one week out of four, beginning in the fall of 1956, as part of the prestigious CBS anthology series Playhouse 90 (1956-61).

As a young teen I watched some of those films. Until recently the only one I had revisited as an adult was So Soon to Die (January 17, 1957), starring Richard Basehart and Anne Bancroft and based on the novel of the same name by Jeremy York, one of the many bylines of the hyper-prolific John Creasey (1908-1973).

A few weeks ago I came upon another, one that I hadn’t seen in more than half a century. The Dungeon (April 10, 1958), written and directed by David Swift, starred Dennis Weaver as a man who, after being acquitted of murder, is kidnapped by a psychotic ex-judge and locked up in a cell in the attic of his isolated mansion, along with several other acquitted defendants.

A great noir premise and a great cast to boot — Paul Douglas, Julie Adams, Agnes Moorehead, Patty McCormack, Patrick McVey, Thomas Gomez, Werner Klemperer, the list goes on and on. And the tension is heightened by the magnificently ominous music of a never credited Bernard Herrmann.

I wish Swift had provided a backstory to explain what turned the judge into a sociopath, and my mind, not to say my nose, boggles when I start wondering how his prisoners (one of whom has been held for more than a year!) ever showered or kept clean-shaven or changed clothes. But if you have the good fortune to find this film on DVD as I did, it’s well worth seeing and, thanks to Herrmann, hearing.

The Poetry Corner has been on sabbatical lately but I need to bring it back in order to tout perhaps the finest detective novel to deal centrally with the subject.

The author was Nicholas Blake, known outside our genre as C. Day Lewis (1904-1972), poet laureate of England and the father of actor Daniel Day-Lewis. The detective, as always except in Blake’s non-series crime novels, is Nigel Strangeways.

The title is Head of a Traveler (1949). Thomas Leitch in his essay on Blake in Mystery and Suspense Writers, Volume 1 (Scribner, 1998), describes the novel as “one of his most tormentedly introverted. The central figure is the distinguished poet Robert Seaton, whose household is destroyed by the unexpected discovery of his vanished brother Oswald’s decapitated corpse. The events of the fatal night remain obscure even after Strangeways’ final explanation; the real interest of the novel is in its impassioned examination of the costs of poetry — the lengths to which poets and those who love them will go in pursuit of their craft.”

Anthony Boucher in his short-lived “Speaking of Crime†column in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (August 1949) was a bit less enthusiastic: “Blake knows so much about his theme, the nature of poetic creation, that he never quite conveys it convincingly to the reader.”

Whichever critic is right, when it comes to the intersection of crime fiction and poetry, Head of a Traveler remains the “locus classicus.â€

Sun 31 May 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

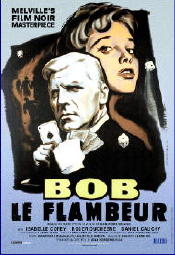

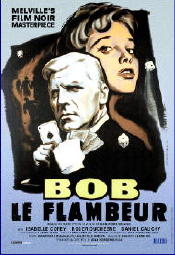

BOB LE FLAMBEUR. Mondial, France, 1956; William Mishkin, US, 1959, as Bob the Gambler. Isabelle Corey, Daniel Cauchy, Roger Duchesne, André Garet, Gérard Buhr, Guy Decomble. Director: Jean-Pierre Melville.

One of the advantages of being something of a round peg in a department of square holes is that I am occasionally allowed to teach something that “nobody else” has any interest in doing, like the course on French Film that I have just finished teaching.

Most of the films are by directors like Renoir, Clair, Virgo, Carne, and Ophuls, but I always manage to slip in a genre film by a director not many people would consider essential. In past years this meant films by Clouzot (Le Cor beau and Jenny Lamour).

This year it was Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1955 thriller, Bob le flambeur (Bob the Gambler), a film that Melville had repudiated before his death in 1972 (“I will not allow this film ever to be screened again”) but that many critics now consider to be his finest achievement in a series of studies of criminals and the criminal milieu.

Ostensibly, Bob the Gambler is an extended character study leading to a climactic caper, the robbery, by a team of well trained specialists, of the casino at Deauville.

But Melville manages to undermine almost every cliche of the caper film with a rigorously analytic style that manages to distance the spectator from the characters and cut away from the caper at the climactic moment, only returning to it in the final moments to dispense almost briskly with the basic plot elements and provide a final, comically ironic look at the protagonist, Bob the gambler.

Melville, in an interview, related how, after seeing Huston’s film The Asphalt Jungle, he realized that he no longer wanted to — or could not — make a classic caper film. He decided instead to make what he called a “comedy of manners” (“comedie de moeurs”), but most American viewers will probably, like the students in my class, find this an odd film indeed.

Melville’s film preceded New Wave films like Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Godard’s Breathless by about four years, but the look of the film (shot on location in the streets and buildings of Montmartre) and the use of a jazz sound track seem to look forward to the innovative filmmaking of the late fifties and early sixties.

The credits are presented over shots of Montmartre from the “heights” of Sacre-Coeur (the church) to the “depths” of Place Pigalle, a moral distance underlined by the matter-of-fact narration of Melville.

But the spectator who expects an explicit moralistic study of the contrasts between the sacred and the profane will be disconcerted as the camera prowls restlessly along the streets, into the back rooms of cafes and restaurants, with Sacre-Coeur only present as a shape dimly glimpsed through the closed curtains of Bob’s elegant apartment.

The affection the camera shows for the landscape may be disconcerting to the viewer who is looking for a narrative thread that will engage him, but location filming is a prominent feature of New Wave films, as in The 400 Blows, whose “travelogue” beginning is reminiscent of the beginning of Bob, all the more so in that both films benefited from the same superb photographer, Henri Decae.

The final shot in Bob is of an empty car parked on a lonely stretch of beach and completes a circle initiated by the documentary shots of buildings at the beginning of the film.

The inner life of the characters is never explored in a way that is satisfying to the viewer, and it is perhaps appropriate that the frame is emptied of people at the beginning and the end.

The viewer expecting the tight plotting of Hitchcock or the claustrophobic, fatalistic character study of Huston, will be disappointed. In Melville’s work, fate is chance, but the camera lingers on geometric patterns (wall-paper, windows, a floor covering) that suggest an intercrossing of plot lines that will only be evident on repeated viewings.

The characters are elusive and the “content” of their relationships is like a crossword puzzle that may or may not be correctly filled in by the spectator.

Melville’s expressed wish that the film not be re-released has been ignored. The formal, discreet patterns of this apparently open but controlled narrative with something of the look of a photograph by Walker Evans have lost none of their capacity for frustrating the viewer accustomed to the heightened, mounting suspense of Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950) or Kubrick’s The Killing (1956).

All three of these films are about defeat and loss, but Bob manages to retrieve an ironic victory from a failure, and the sardonic humor of this victory appears to clash with the conventions it has intermittently adhered to.

In Breathless, Goddard paid tribute to Melville by including, a reference to the character, Bob (Roger Duchesne), and by using Melville to play the role of a novelist interviewed by Patricia, the young American with whom the small-time Parisian hoodlum, Michel, has fallen in love.

She betrays Michel, echoing the thematics of betrayal in Bob, where Anne (Isabelle Corey) betrays Paulo and Bob’s careful planning, but the final irony is perhaps Melville’s attempted betrayal of his beautiful and still fascinating portrait of Bob the gambler and his Parisian milieu.

And one can only wonder to what extent Godard was again tipping his hat to Melville when one of his characters comments that he and his friends avoid Montmartre, which is dangerous for them and their “kind.”

But Godard met successfully the cinematic challenge of his gifted predecessor and his tribute is, finally, the best witness to Melville’s achievement.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

Sat 30 May 2009

BRUTE FORCE. Universal International, 1947. Burt Lancaster, Hume Cronyn, Charles Bickford. Yvonne De Carlo, Ann Blyth, Ella Raines, Anita Colby, John Hoyt, Howard Duff, Whit Bissell, Art Smith. Director: Jules Dassin.

A movie that takes place almost entirely behind the walls of a prison is not likely to have many women in it, and if it weren’t for brief flashbacks, there wouldn’t be any at all. Anyone in 1947 who paid 25 cents to see Yvonne De Carlo in this film should have marched right up to the box office afterward and demanded his money back.

In spite of the posters and lobby cards, a prime example of which you can see below, Miss De Carlo graces the screen for less than five minutes, but I have to admit, she makes the most of them.

In this movie she plays the Italian girl friend of the GI in World War II (Howard Duff) who took the rap for her after she shot her father when he broke down and tried to turn him in to the authorities.

In fact, it seems that the women in their lives are part of the stories of all of the men in Cell R-17, in one way or another.

Some are weak (Whit Bissell) and some are strong (Burt Lancaster), but none are really evil — except perhaps Joe Collins (Lancaster), who seems to be a leader of a small gang but whose soft spot is a crippled woman whom he loves (and who does not know what he did for a living).

No matter. When Burt Lancaster glowers at you, with those dark accusing eyes, you know you’ve been glowered at. This seems to have been only his second movie, the first being The Killers (1946), and if his performance in that earlier picture didn’t make an impression on the movie-going public, this one surely did. Joe Collins means to escape, and he doesn’t care how.

Standing in his way, however, is not the weak-kneed warden, who simply wants everyone to get along — including Gallagher, the grizzled but pacifistic Charles Bickford who’s in charge of the prison newspaper and expecting to get a parole any day now. No, the other person whose role in this movie you will remember for a long time is Captain Munsey (Hume Cronyn), the slim but sneering and slickly sadistic head of the prison guards whom everybody locked up inside hates with a passion, to the utmost fiber of their being.

Some prisoners break under his thumb of iron, some don’t. The ending of this movie — I don’t think it will surprise anyone if I say that indeed there is a break-out eventually does take place — is filled with the chaos of lights blazing, sirens wailing, and the sound of gunfire ringing off the walls.

Who gets out, who survives? That I can’t tell you, but I can tell you this. No one walked out of the movie when it was playing, and no one asked for their money back. (That the movie gets a little preachy toward the very end is forgivable. No one paid any attention to that anyway. Prison life was hard in 1947, and while it may have changed, it never got any easier.)

Sat 30 May 2009

MICHAEL ALLEN – Spence and the Holiday Murders. Walker, hardcover, first U.S. publication 1978. UK title: Spence in Petal Park: Constable, hc, 1977. Paperback reprint: Dell, February 1981; Scene of the Crime #14.

The season is Christmas, the victim is a swinging young bachelor with an unsuspected habit of snapping photos through the windows of the girls’ school across the way, and so the immediate conclusion is that someone was being blackmailed.

As everyone has come to expect of the British police procedural, Detective, Superintendent Spence’s investigation is carried out so diligently and smoothly that it could as well serve as a primer for the novice mystery reader.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979.

Bibliographic data. [Expanded from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin] —

ALLEN, MICHAEL (Derek) 1939- . Pseudonym: Michael Bradford. SC: Supt. Ben Spence, in all below:

Spence in Petal Park. Constable 1977.

Spence and the Holiday Murders. Walker 1978. Reprint of Spence in Petal Park.

Spence at the Blue Bazaar. Constable 1979.

Spence at Marlby Manor. Walker 1982.

BRADFORD, MICHAEL. Pseudonym of Michael Allen.

Counter-Coup. Muller, hc, 1980; Critics Choice, pb, 1986. “Rebels overthrow the South African government and President Kasaboru is on the run with Philip Morgan, formerly of the Metropolitan Police.”

Sat 30 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAN STUMPF:

JOHN P. MARQUAND – Think Fast, Mr. Moto. Little Brown, US, hardcover, 1937. Robert Hale, UK, hc, 1938. Film: TCF, 1937 (scw: Norman Foster, Howard Ellis Smith; dir: Foster). Reprinted several time in both hardcover and soft, including Pocket #59, June 1940 (shown).

The film version of Black Magic seemed to have set off a wave of let’s-go-back-and-read-that-again, which washed John P. Marquand’s 1936 novel Think Fast, Mr. Moto up onto the shores of my consciousness.

Marquand won a Pulitzer for a book nobody reads anymore, and I’m afraid he’ll generally be remembered more for Moto than for Apley. At that, Think Fast is readable enough, fast enough, mildly surprising in its way, and readily forgettable.

Something about a Nice Young Man coming to Hawaii to untangle the affairs of a distant, hostile and beautiful relative, getting enmeshed with crooks and smugglers and all that sort of thing. It’s the kind of book that can be flatteringly described as Vapid; not bad, really, but remarkably unremarkable.

I particularly liked the way the characters seemed pulled out of Hollywood B-movies. When Marquand pits his hero and heroine against an amusing gangster, Chinese warlord, sallow Russian and the redoubtable Mr. Moto, one can’t help but picture Bob Cummings, Dolores Del Rio, Lloyd Nolan, Warner Oland, Mischa Auer — and of course, Peter Lorre.

One thing I found rather disturbing, though: when Marquand wrote this thing, Japan was raping China; they were doing to China what Hitler did to the Jews, in one of the most brutal invasions in history. But in Think Fast, Mr. Moto, the bad guys are all plotting to smuggle supplies to the disparate elements in China fighting the Japanese, and our nice young man helps Mr. Moto put a stop to all this to keep his family from scandal.

Makes one wonder where Marquand’s moral compass was.

Fri 29 May 2009

UNCOMMONLY DANGEROUS: ERIC AMBLER ON TV

by Tise Vahimagi

The early literature of Eric Ambler belongs with such contemporaries as Graham Greene and Geoffrey Household: novels which plausibly construct their dark and ominous prophesies of quiet disaster and which find the power game, as played out by ordinary people on intercontinental trains and across shifting frontiers, more imaginatively stimulating than the one-man antics of the post-Ian Fleming era.

Above all, Ambler’s novels have that air of confident enjoyment in the game they are playing which is so easily conveyed to the reader: his works are entertainments, in Greene’s sense of the word, and, undeniably, intelligent ones.

It is a truism that Ambler was the founding father of the modern political thriller, the writer who brought the genre to maturity in the 1930s. In just six novels, from The Dark Frontier in 1936 to Journey into Fear, 1940, he created the distinctive form that was to have a seminal influence on all writers in the genre.

In the late 1930s, he had strong anti-fascist leanings and his stories reflected the political tensions of the time, when Europe was about to explode. Before he rewrote the conventions of the spy thriller, the genre was epitomised by Sapper’s thuggish Bulldog Drummond and Buchan’s Hannay, officer-class heroes with little more than a gung-ho approach to life and its problems.

Moreover, detective stories of the day (by the likes of Dorothy L. Sayers) were considered respectable; thrillers in the former vein were not. Happily, Ambler changed all that.

His heroes were genuinely ordinary people, amateurs of a kind closer to Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden. They stumbled into complex situations, where they had to make tough choices under pressure. A romantic sense of Ruritania gave way to a more precise Italy, France and Turkey preparing for a second world war.

As we know, four of his six pre-war novels became films (of varying merit). The Mask of Dimitrios (Warner Bros, 1944; from A Coffin for Dimitrios) and Journey into Fear (RKO, 1943) remain consistently enjoyable with a nice tangle of mystery and suspense.

Background to Danger (WB, 1943; from Uncommon Danger) provides a suitably menacing, violent atmosphere for Greenstreet and Lorre to display their familiar brand of icy unpleasantness.

The British production, Hotel Reserve (RKO, 1944; from Epitaph for a Spy), already reviewed and discussed in detail here, looked better (thanks to camera operator Arthur Ibbetson) than it perhaps deserved.

For the most part, the television work of an author (whether as adaptations of their work or as original teleplays) is generally regarded — when it is regarded at all — as less than worthy of interest. My view is that all of an author’s work is of interest. The TV representations of Ambler’s work are, admittedly, more often less-than-rewarding but are still worthy of examination.

His earliest work to appear in a television translation was the espionage thriller Epitaph for a Spy (1953), a BBC-produced six-part serial dramatised by Giles Cooper and featuring Peter Cushing as the innocent-in-a-spot teacher Josef Vadassy. The following year, CBS adapted the story (drawing on the services of three writers) for their anthology series Climax! (CBS, 1954-58), starring Edward G. Robinson as the frightened, bumbling character.

BBC-TV returned to Ambler’s story again in 1963 for a four-part serial (dramatised by the usually dependable Elaine Morgan). Unfortunately, the producers, seemingly lacking confidence in the 1938 work, decided to condense the story into four instalments and, of all things, update it to the 1960s (changing nationalities, providing new motives and readjusting relationships). It is indeed unfortunate that the 1953 BBC version no longer exists; it should be considered a small mercy that there is no sign of a recording of the 1963 ‘satire’.

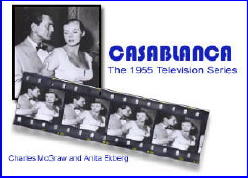

Although A Coffin for Dimitrios was not afforded an adaptation for television as such, the basic plot turned up as “Satan’s Veil” (1956), an episode of the Warner Bros. TV drama Casablanca (ABC, 1955-56).

The storyline (presumably a Warner property since their 1944 The Mask of Dimitrios) was reworked in the form of an adventuress (the sultry Rossana Rory) trying to conceal the details of her faked death from Charles McGraw’s hard-boiled Rick.

Considering that other WB works were given a small-screen adaptation (“Casablanca”, in 1955; “Mildred Pierce”, 1956; “To Have and Have Not”, 1957, etc.) via the adventurous Lux Video Theatre (CBS/NBC, 1950-57), one wonders why the perfect-for-TV Dimitrios was overlooked.

The other Climax! presentation was a lamentable “Journey into Fear” (1956) with a quivering John Forsythe as a terrified-out-of-his-wits American engineer whose life is endangered in Istanbul and then shipboard to Genoa by ever-present assassins. Hitchcock television regular James P. Cavanagh adapted Ambler’s 1940 novel.

The Schirmer Inheritance (ITV, 1957), involving a New York attorney’s search for the rightful heir to a $4,000,000 inheritance, was adapted into a six-part serial by Kenneth Hyde for Britain’s ABC-TV company. Not so much a wary passage through post-war Europe (in the Greene/Third Man vein) as a gallery of suspicious figures in a rather over-talky journey to a bandits’ lair on the Yugoslav-Greek border.

Ambler moved to Hollywood in the late 1950s and, in 1958, married long-time Hitchcock collaborator producer-writer Joan Harrison, who was at that time producing the Alfred Hitchcock Presents (CBS/NBC, 1955-62) and Suspicion (NBC, 1957-59) anthologies.

For the latter collection (where he met Harrison), Ambler wrote the soft mystery “The Eye of Truth” (1958) featuring Joseph Cotton as a blackmailed corrupt attorney who’s trying to cover up some incriminating documents. In 1962 he was brought on-board the Alfred Hitchcock Presents series to adapt a Nicholas Monsarrat short story as the episode “Act of Faith” (1962) in which an aspiring author seeks finance from a successful novelist, with unexpected repercussions. (This was Ambler’s second adaptation of a Monsarrat work; the first, the screenplay for the 1953 wartime drama The Cruel Sea, earned him an Oscar nomination.)

Perhaps his most curious and direct television contribution was as creator of the mystery series Checkmate (CBS, 1960-62), an often satisfying who’s-going-to-do-it drama involving a trio of San Francisco private investigators: their job, and the series’ hook, being to prevent crimes before they happen.

Although it was intimated at the series’ launch that Ambler himself would be contributing original stories, the series did employ the tantalising talents of many respected crime-mystery writers, including Leigh Brackett, Jonathan Latimer and William P. McGivern. The hugely enjoyable “The Terror from the East” (1961) episode (written by Harold Clements), with a highly suspicious, shambling Charles Laughton as a visiting missionary from China, has our heroes running in circles like hypnotised rabbits.

A later, similarly formatted series, The Most Deadly Game (ABC, 1970-71), created by Mort Fine and David Friedkin (for Aaron Spelling Productions), featured three criminologists who, rather than preventing crimes, engaged in solving offbeat whodunits. Since Joan Harrison was one of the series’ producers (along with Fine & Friedkin) one can be less than surprised by the similarity.

Although some modern sources have credited Ambler with the development of The Most Deadly Game, Fine and Friedkin are the only ones to receive a ‘created by’ credit.

An additional point of interest: a co-writer credit for the episode “Model for Murder” (1970) goes to the fascinating but elusive Elick Moll who, in collaboration with Frank Partos, wrote the screenplay for the hauntingly Woolrichian Night Without Sleep (20th Fox, 1952), based on Moll’s original treatment (and published as a novel in 1951).

For Alcoa Premiere’s “Pattern of Guilt” (1962), Ambler, as producer of the episode, hired Helen Nielsen to compose an original teleplay for what may have been a proposed series’ pilot episode. The story involved Ray Milland as a reporter who is assigned to cover a series of murders, all spinsters, where related clues are found at each murder scene. Little seems known about this one; why Ambler suddenly became a producer (if in fact so), was it actually intended to spin-off a Milland-as-reporter series?

Following up the association with Aaron Spelling Productions, Ambler wrote and Harrison produced Love, Hate, Love (ABC, 1971), an annoyingly tedious TV movie thriller starring Ryan O’Neal and Lesley Warren as a couple stalked by Warren’s psychotic ex-boyfriend (Peter Haskell).

The next of Ambler’s spy stories to be adapted for the small screen was the four-part A Quiet Conspiracy (ITV, 1989). Taken from his 1969 novel The Intercom Conspiracy, the post-le Carré plot follows former journalist Joss Ackland and his daughter Sarah Winman as they stumble about in an international conspiracy involving a secret NATO spy satellite. The red herring fishery was worked overtime, thanks to producer Anglia TV’s co-production casting of various, unfamiliar European actors.

With The Care of Time (ITV,1990), another made-for-TV film (Anglia TV), adapted from Ambler’s 1981 novel, the central character, an American ghost writer (a baffled Michael Brandon), is an outsider who is drawn into an overly-complicated web of international intrigue.

The puzzling plotting and colourful scenery moves (totters, at times) from Pennsylvania, across Europe to the Austrian Alps, collecting Christopher Lee’s political fixer, who’s ducking his enemies, and his attractive body-guard (Yolanda Vazquez) along the way. An ambitious TV film with a reach that was greater than its grasp.

A couple of Footnotes: one of relevance to the above television work; the other because it’s an irresistible connection.

(I) In 1965, US trade journals began making brief, intriguing references to the production of a pilot episode (“The Seller’s Market”), written by Ambler, for a proposed espionage series called Journey Into Fear for NBC; the episodes would revolve around star Jeffrey Hunter as a scientist who is drawn into working for the CIA.

Completed (and an hour in length), the series was rejected by the network and the pilot episode was despatched to the vaults. Perhaps the partnership of Ambler and the 1960s Spy Boom would have been an awkward one (he had a dislike for master-villains, pseudo-scientific gadgets and the general paraphernalia that characterised the 1960s spy genre), but the possibilities still fire the imagination.

For a fuller report on this unsold series, check this link for Glenn Mosley’s (University of Idaho) absorbing survey.

(II) Geoffrey Household merits some reference here, not only because Ambler wrote the screenplay for Rough Shoot (1953; aka Shoot First), based on his 1951 novel, but that Household’s espionage/adventure characters belong to the same fold as Ambler’s victims of circumstance.

His most famous work is of course Rogue Male (1939), becoming the much praised Fritz Lang film Man Hunt in 1941 and, in 1976, an equally commendable TV film starring Peter O’Toole. Another TV film, Deadly Harvest (1972), was made from his 1961 novel Watcher in the Shadows.

Two early Suspense (CBS, 1949-54) episodes based on Household stories (“Death Drum”, 29 Jan 1952; “Woman in Love”, 26 Aug 1952) can be viewed on the Internet Archive. (Follow the links provided.)

Eric Ambler Television:

1. Epitaph for a Spy (serial; BBC, 14 March-18 Apr 1953; 6 x half-hour). Producer/Director: Stephen Harrison. Scr: Giles Cooper, from 1938 novel. Cast: Peter Cushing (as Vadassy), Ferdy Mayne, Warren Stanhope, Joan Winmill.

2. “Epitaph for a Spy” / Climax! (CBS, 9 Dec 1954). Dir: Allen Reisner. Scr: Donald S. Sanford, David Friedkin, from Ambler novel. Cast: Edward G. Robinson (Vadassy), Melville Cooper, Marjorie Lord, Dave O’Brien.

3. “Satan’s Veil” / Casablanca (ABC, 31 Jan 1956). Dir: Alvin Ganzer. Scr: Norman Lessing, Nelson Gidding, from ‘story’ by Ambler. Cast: Charles McGraw, Marcel Dalio, Rossana Rory, Dan Seymour.

4. “Journey into Fear” / Climax! (CBS, 11 Oct 1956). Dir: Jack Smight. Scr: James P. Cavanagh, from 1940 novel. Cast: John Forsythe (as Graham Johnson), Eva Gabor, Arnold Moss, Anthony Dexter.

5. The Schirmer Inheritance (serial; ITV, 3 Aug-7 Sept 1957; 6 x half-hour). Prod: Stuart Latham. Dir: Philip Dale. Scr: Kenneth Hyde, from 1953 novel. Cast: William Sylvester, Vera Fusek, Jefferson Clifford.

6. “The Eye of Truth” / Suspicion (NBC, 17 Mar 1958). Prod: Alfred Hitchcock. Dir: Robert Stevens. Scr: Eric Ambler. Cast: Joseph Cotton, George Peppard, Leora Dana, Philip Van Zandt.

7. Checkmate (series; CBS, 1960-62). Created by Eric Ambler. Regular Cast: Anthony George (as Don Corey), Doug McClure (Jed Sills), Sebastian Cabot (Dr. Carl Hyatt).

8. “Pattern of Guilt” / Alcoa Premiere (ABC, 9 Jan 1962). Prod: Eric Ambler. Dir: Bernard Girard. Scr: Helen Nielsen. Cast: Ray Milland, Myron McCormick, Joanna Moore, Olive Carey.

9. “Act of Faith” / Alfred Hitchcock Presents (NBC, 10 Apr 1962). Dir: Bernard Girard. Scr: Eric Ambler, based on a story by Nicholas Monsarrat. Cast: George Grizzard, Dennis King, Florence MacMichael, Jeno Mate.

10. Epitaph for a Spy (serial; BBC, 19 May-9 Jun 1963; 4 x half-hour). Prod/Dir: Dorothea Brooking. Scr: Elaine Morgan, from Ambler novel. Cast: Colin Jeavons (Vadassy), Burnell Tucker, Janet McIntire.

11. Love, Hate, Love (TV film; ABC, 9 Feb 1971). Dir: George McCowan. Scr: Eric Ambler, based on story by Ambler, Robert Summerfield. Cast: Ryan O’Neal, Lesley Ann Warren, Peter Haskell, Henry Jones.

12. A Quiet Conspiracy (serial; ITV, 24 Feb-17 Mar 1989; 4 x hour). Prod: John Rosenberg. Dir: John Gorrie. Scr: Alick Rowe, from 1969 novel The Intercom Conspiracy. Cast: Joss Ackland (as Theodore Carter), Sarah Winman, Hartmut Becker.

13. The Care of Time (TV film; ITV, 26 Aug 1990). Dir: John Davies. Scr: Alan Seymour, from Ambler novel. Cast: Christopher Lee, Yolanda Vazquez, Ian Hogg, Michael Brandon.

Footnote: “Seller’s Market” / Journey into Fear (1966 pilot episode; not transmitted). Prod: Joan Harrison. Dir: Robert Stevens. Scr: Eric Ambler. Cast: Jeffrey Hunter.

EDITORIAL COMMENT. Eric Ambler was born 28 June 1909, so next month will mark the 100th anniversary of his birth. We apologize for jumping the gun by a few days, but we welcome the opportunity to toast here and now one of the greatest spymasters of all time.

Fri 29 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

JOHN HAWKES – The Lime Twig.

New Directions, paperback, 1961; reprinted several times & still in print. UK edition: Neville Spearman, hardcover, 1962.

If you’ve ever wondered what a Gold Medal novel or Dick Francis thriller written by a literary icon would be like then The Lime Twig should be your cuppa. John Hawkes is a legendary figure in the American literary world probably best remembered for his erotic novels Traveler and Blood Oranges, but his breakthrough novel is The Lime Twig, an expanded novella about a lower middle class English couple whose boredom leads them into a downward spiral of crime, violence, and death.

Michael and Margaret Banks are befriended by William Hencher, who decides to do them a good turn by letting them in on a sure thing — the hijacking of a race horse. But from the beginning things go wrong. Hencher is killed in the heist, and Michael is chosen by the gang to take his place as their front man, kept quiet by the sexual lure of two women. When Margaret becomes suspicious she is kidnapped, and after Michael becomes enamored of one of the femme fatales, Sybilline, she is raped and murdered. When Michael tries to free himself he too meets his fate.

The book is written in a lush nightmarish style that gives the novel the feel of descending into a dream world where nothing is quite what it seems to be. Michael is caught up in an erotic dream and Margaret in an erotic nightmare until both their fates dovetail in death.

The chapters are separated by articles by a sports journalist, Sidney Slyter, whose commentary was insisted upon by the publisher to keep the reader from being too confused. You can use them for that purpose or skip them, but don’t expect a suspense novel in the usual sense. Suspense, at least what we mean by suspense, isn’t really Hawkes’ point or interest.

It’s that kind of a book.

Still, as literary writers go, Hawkes is never dull and has genuine ability. The Lime Twig doesn’t really work as a crime novel, but it does work as a study of human nature and a portrait of innocent individuals caught up through no real fault of their own in a growing nightmare, even if it comes in the guise of a favor and an erotic gift.

Hawkes’ most accessible novel was Adventures in the Alaskan Skin Trade, a novel about an Alaskan Madam who operates a fly in brothel. He is almost always interesting and often treads on the dark side of human nature. Others than those I’ve mentioned, you might also try his novel Whistlejacket.

That said, whether or not you want to read a book like The Lime Twig depends a great deal on your tolerance for literary style (and pretense), and your understanding going in that this is not Elmore Leonard or John D. MacDonald.

However much it may sound like a Gold Medal original, its aims and intent are in other areas, and anyone expecting a thriller is apt to be disappointed. The Lime Twig has the same relation to most crime novels that Donald Gammell’s film Performance has to most gangster films.

But understanding that, Hawkes is a good writer, never pretentious or full of himself, and certainly The Lime Twig has a nightmarish quality many a suspense writer would envy.

As a crime novel it is a curiosity, as a literary novel a small masterpiece. Hawkes is an excellent writer, but he’s not for all tastes and admittedly can be difficult going — especially if you have a low tolerance for literary style. He writes beautifully, and can even be entertaining, but he’s not basically an entertainer. The darkness in his books can make Cornell Woolrich look like a cockeyed optimist.

This is a worthy book, but if you read it, I hope you don’t think you’re going to find a thriller. If you decide to read it and hate it, remember, I warned you going in.

___

Bibliographic data: You can find all a list of all of John Hawkes’ contributions elsewhere online. This website is one that will do very nicely. The Lime Twig is not currently in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, but from David’s review, I (Steve) think it should be. His entry in CFIV presently looks like this:

HAWKES, JOHN (Clendennin Burne, Jr.) 1925-1998.

Death, Sleep, and the Traveler (New Directions, 1974, hc) [Ship] Chatto, 1974.

Whistlejacket (U.S.: Weidenfeld, 1988, hc) [England] Secker, 1989.

[UPDATE] 05-30-09. Al agrees. In it goes. The book will appear in the next installment of the online Addenda to the Revised CFIV.

Thu 28 May 2009

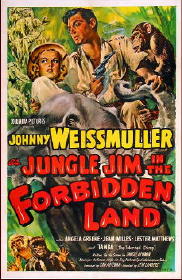

JUNGLE JIM IN THE FORBIDDEN LAND. Columbia, 1952. Johnny Weissmuller, Angela Greene, Jean Willes, Lester Matthews, William Tannen. Based on the comic strip character created by Alex Raymond. Director: Lew Landers.

I was joking around in the comments following my recent TCM Alert, posted here, saying something like this, and I quote:

“As for Jungle Jim — the movies, that is — I remember seeing them at the local movie theater when I was 10 or 12, and thinking even then that they weren’t very good. I suspect that, as you seem to be hinting, they haven’t improved with age.

“No matter. I’ll tape them anyway. Nobody says I have to watch them — but I probably will. Call me curious.”

My goodness. I did watch one, this one, and I have to tell you, assuming that it’s typical of the rest of the series (*), I didn’t really realize how bad they were. The funny thing is, I’ve just checked some of the reviews this mess of a movie has had over the years. They’re generally favorable, and the movie is simply awful. I’d have to stretch like Plastic Man to say anything positive about it, and then I’d be lying to you.

(*) This was number eight of either 13 or 16 films in the series. The last three Johnny Weissmuller essentially played himself after Columbia lost the use of the name of the Jungle Jim character. So unless I’m told otherwise, I’ll assume this one’s typical enough.

But by golly, they must have been successful. They wouldn’t have kept making them if people hadn’t kept going to see them. This one’s barely an hour long, but without all of the stock footage of various animals found in all four corners of the world, it probably wouldn’t have been run much over 30 minutes or so.

That plus a plot that makes no sense at all. To sum it up: ivory, a tribe of giant people, a lady anthropologist (the beautiful Angela Greene, whom you can see in the photo with Jim), rampaging elephants, greed – as exemplified by the truly and magnificently hard-boiled Denise (Jean Wiles), a chimp that does nonsensical things to make the kid folks laugh, and a rookie governmental commissioner who doesn’t know which end is up.

Did I mention a crooked native chief? Truth serum? Well I have now.

The costumes of the giant people (all two of them) were left over from some werewolf movie, I’m afraid to say. I hate to say this also, but the only reason that this review is so long – it’s probably going to take me longer than watching the movie itself to get it typed, formatted and posted – is so there’s room to fit all of the images in.

But I especially like this small movie theater flyer I found online. I certainly remember those from either of the two theaters in the town that I grew up in, but I hadn’t seen one in many a year until today.

In fact, the name of the theater on this very same promotional flyer is the Lyric, one of the two theaters I was just referring to. I’d wonder if it were the same one, but I imagine every other small town in the 1950s had a Lyric Theatre.

PostScript. If you read the review carefully, you’ll discover that I lied to you. There are some positive aspects to this movie, and I mentioned them both.

Thu 28 May 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

EARL DERR BIGGERS – Keeper of the Keys. Bobbs-Merrill, US, hardcover, 1932. Cassell, UK, hc, 1932. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback.

I recently went back to a simpler time and reread Keeper of the Keys, by Earl Derr Biggers, the last of the Charlie Chan novels. Those who know Chan only from the B-movies of the ’30s and ’40s will be pleasantly surprised at how readable and well plotted the six books about him are.

Charlie, at Lake Tahoe to find the missing son of millionaire Dudley Ward, encounters his first taste of snow. The plotting is deft, and there is depth in the portrayal of Chan, especially his reactions to bigotry and “Americanization.”

Aphorisms, those sayings which occur in most Chan movies, seem more appropriate here as they embody Chan’s detective methods. As he gathers clues, he says, “We must collect in leisure what we may use in haste. The fool in a hurry drinks his tea with a fork.”

When Chan sits down to weigh the clues, he remarks, “Thought is a lady, beautiful as jade. Events of tonight make me certain I must not neglect the lady’s company longer.”

Most mysteries written more than fifty years ago are far more dated. Fortunately, those in the Chan series are notable exceptions.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (slightly revised).

Thu 28 May 2009

THE GOLDEN AGE OF BRITISH MYSTERY FICTION, PART VII

Reviews by Allen J. Hubin.

A Stranger Came to Dinner by Andrew Soutar (Hutchinson, 1939) is a fairly vigorous specimen of the 1930s British thriller, involving London inquiry agent Phineas Spinnet in an espionage affair.

At first sight it seems to involve only a straightforward murder, as Sir Peter Greebe is battered to death in his mansion while a bizarre collection of international guests is enjoying his hospitality. The Yard is invited in and Spinnet is hired by a newspaper to poke about and report.

At least he does the former, and the case quickly becomes murkier. A Japanese house guest is found hanged in a sealed room in which there is no place from which the rope could have been suspended — but little is made of this impossibility and the solution is casually revealed. Spinnet’s role becomes official and involves, among other perils, a fall from an airplane and torture in Portugal.

There seems to be some sinister threat against Britain, and the name of the mysterious secret agent known as the Buzzard (friend or foe? live or dead?) circulates. Spinnet, playing both ferret and bait, catalyzes a surprising resolution.

***

Robert Machray‘s Sentenced to Death (Chatto, 1910) dates from an age when men were strong and silent and women pure. Its subtitle is “A Story of Two Men and a Maid,” and so it is.

The maid is Zilla Barradell, pure and wealthy, who while taking the cure in the brine baths at Wyche meets one of the men. This is Halliday Browne, strong and silent, silent especially on the subject of his secret service activities in India, the sentence of death by Indian extremists which hangs over his head, and his growing love for Zilla.

The other man is Fernando Valdespino, a weak villain with a penchant for losing money at cards. Zilla does not see beyond his handsomeness and allows him to spike her relationship with Browne. Meanwhile a plot to bring terror and violence to England has been uncovered, and Browne, as chief investigator and principal target, is drawn into the fray.

Who are the nasties in this scheme and who, besides Halliday, are their targets, and where are they hiding out? A diverting period piece, straightforward and predictable, is this — a romantic thriller, not a detective story.

***

I am well pleased with the first Paul McGuire tale I’ve read, Murder by the Law (Skeffington, 1932). McGuire seems to have a certain currency: Barzun & Taylor speak well of at least some of his works, and his books (especially those not published in the U.S., like this one) were (at least in my book-collecting years) both sought and scarce.

The plot and setting in Law are certainly acceptable but not exceptional. Rather more significant are the characters McGuire sketches for us, and his skillful and evocative use of language, particularly in dialogue.

One overly hot week of an English summer various people, including the curious folk of the New Health and Eugenist persuasion, gather at Bellchurch on the Sea. Also among the gatherers is Harold Ambrose, a poisonous novelist toward whom McGuire directs his most inspired venom. While someone else directs a blunt object…

Ambrose’s battered corpse is found on the beach, and Supt. Fillinger — trailed by narrator Richard Tibberts and painter-sleuth Jack Savage — thrusts his elongate form into a social realm containing at least one satisfied and accomplished killer.

***

Although Rogues in Clover by Percival Wilde (Appleton, 1929) is listed in ?Queen?s Quorum,? is hideously scarce (only this first hardcover edition was ever published, to my knowledge), and has been sought after feverishly by collectors with deadly glints in their eyes and bankrolls in their fists (I came by my copy in an curious fashion in a one-time visit with dealer/ author Van Allen Bradley), as one American entry in this set of reviews, it barely qualifies as marginal mystery/detection.

We are introduced, in an opening chapter (?The Symbol?) to Bill Parmalee, son of a wealthy Connecticut farmer. Parmalee fled hearth and home to become a card sharper, pursuing a career of cheating which had its ups and downs, one of the latter finding him, unexpectedly, in his home town.

He thought then to visit his widower father, who spurned him because of his life of crime. A duel over a deck of cards ensued, in which his father reawakened all those good instincts Bill had submerged, and Bill is then welcomed back into the paternal bosom.

The remaining seven stories detail the cheating schemes Bill uncovers, usually in poker games and always at the behest of his woolly and wealthy friend Tony Claghorn. These are pleasant tales, nicely told with genteel humor and amusing insight into human nature, and they are better read as such than crime fiction.

***

NOTE: Go here for the previous installment of this column.

Next Page »