Search Results for 'whodunit'

Did you find what you wanted ?

Thu 8 May 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Having eaten up much of the past few weeks paginating the index for JUDGES & JUSTICE & LAWYERS & LAW, I must again rely on my dusty old files to provide raw material for this month’s column.

Lucky for me that my files are full of the stuff. In my salad days, beginning more than half a century ago, I got into the habit of writing for-my-eyes-only reviews not only of the full-length whodunits I read but also of the shorter works variously called short novels, novelettes, novellas and novellos, the last term coined by my beloved Harry Stephen Keeler, who probably pronounced the word with the accent on the first syllable.

From the hundred-odd paragraphs of comment on tales of this length that are moldering in my files I’ll exhume a few that strike me as not too uninteresting today.

Of all the characters who appeared frequently in novellos during the Golden Age, the two who stand tallest are Nero Wolfe and Simon Templar. Among the pile of tales of this length which the young Leslie Charteris (1907-1993) wrote about his Saintly hero, one of my favorites is “The Inland Revenue†(The Thriller, 25 April 1931, as “The Masked Menaceâ€; collected under its better-known title in THE HOLY TERROR, Hodder & Stoughton 1932, and THE SAINT VS. SCOTLAND YARD, Doubleday Crime Club 1932), in which we follow Simon as he tries to raise enough money to pay his income tax by extorting it from a sinister mastermind calling himself the Scorpion.

It’s a preposterously tongue-in-cheek saga with an astoundingly unfair surprise ending, but Charteris carries it off with the help of the satiric wit and brashness that were his trademarks.

When Charteris launched his career, by far the most popular English mystery writer was Edgar Wallace (1875-1932), who produced novels, novellos and short stories faster than a rabbit can produce baby rabbits. One of the most rousing and richly plotted of his tales at the length we’re investigating today was “The Man from Sing Sing†(The Thriller, 7 February 1931; collected in THE GUV’NOR AND OTHER STORIES, Collins 1932, U.S. title MR. REEDER RETURNS, Doubleday Crime Club 1932).

The parlormaid of Mr. J.G. Reeder, perhaps Wallace’s best known series detective, leads her boss into a bizarre case involving a lost false mustache, a spectacular embezzlement, a murdered Eton lecturer and a fortune found in a haystack. Our sleuth connects these and other items with reasoning that runs the gamut from sketchy to non-existent, but Wallace scores with his dry wit, tantalizing plot, swift economy of movement, and loving depiction of English working-class mores.

Baynard Kendrick (1894-1977) created more than one series sleuth but his signature character was the blind detective Captain Duncan Maclain. The captain debuted in 1937 and usually appeared in novels, but during the WWII years he also turned up in three novellos, collected after the war as MAKE MINE MACLAIN (Morrow, 1947).

I don’t have a copy of that book but I do own each of its component parts, and reread one of them recently to see if my opinion of it had changed since 1968. It hadn’t.

In “The Murderer Who Wanted More†(American Magazine, January 1944) one of the potential legatees of a Staten Island matriarch’s estate is shot to death during a fierce snowstorm while traveling on the post-midnight local train from the St. George ferry terminal to the end of the line at Tottenville to visit his dying mother. Both before and after that murder come several attempts on the life of another potential legatee, a lovely young artist who had recently painted Maclain’s dogs.

The captain’s key deduction is unconvincing and the motive Kendrick attributes to the killer shows that he didn’t know the first thing about the law of wills, but the Staten Island setting is unusual and vivid enough.

The earliest collections of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novellos appeared in 1942 and 1944 but contained only two tales apiece. Most of Wolfe’s cases at that length appeared three to a book, but only after threesomes had been published featuring other sleuths including Duncan Maclain, as we’ve just seen, and Michael Shayne, the Miami-based PI created by Brett Halliday (1904-1977).

Fast, complex and professional are the words for “Dinner at Dupre’s†(Mystery Book Magazine, September 1946; collected in MICHAEL SHAYNE’S TRIPLE MYSTERY, Ziff-Davis 1948), in which Mike’s search for the murderer of a prospective client leads him to the hamlet of Cheepwee, Louisiana and a temptingly described Southern dinner with a nymphomaniac who has a new angle on the bigamy racket.

Brisk pace, shrewd plotting, an honest if not startling solution, and minimal self-conscious toughness prompted me a few generations ago to give this one very high marks.

Now we tackle a work actually written not too long before I began to set down some of these scribbles. Richard S. Prather (1921-2007) didn’t turn out a slew of novellos about his quintessentially cool PI Shell Scott, but the few he did were among the joys of my late teens.

Take for instance “Babes, Bodies and Bullets†(Cavalier, April 1958; collected in SHELL SCOTT’S SEVEN SLAUGHTERS, Fawcett Gold Medal pb #S1072, 1961). Hired to solve a Beverly Hills attorney’s murder, which he witnessed, Scott runs into a gaggle of gruesome gangsters, an assortment of luscious wenches and a mounting heap of corpses.

The plot is sorta thin, but Prather’s feel for action and tempo and his wild-and-woolly prose, plus a sequence of gruesome horseplay in an underworld hospital, lift this novello to the top of the heap.

May I stray from the month’s topic for a moment? The last living actor to portray Ellery Queen in any national medium died on March 12, a few weeks short of his 100th birthday. Richard Coogan was best known for TV work — starring in the early live sci-fi series CAPTAIN VIDEO, having a long-running role in the daytime soap LOVE OF LIFE, playing Marshal Matt Wayne on the Western series THE CALIFORNIANS — but he began his career in radio and portrayed Ellery during late 1946 and early ‘47.

Anthony Boucher, who at that time was collaborating on the weekly scripts with EQ co-creator Manfred B. Lee, described Coogan’s performance in a letter to Lee (25 October 1946) as “not quite so smug†as his predecessor’s. Coogan’s main interest in his twilight years was golf. He was in his mid-nineties when I talked with him over the phone in connection with my book ELLERY QUEEN: THE ART OF DETECTION, but he struck me as in amazingly good health, and anyone who checks out his reminiscences of CAPTAIN VIDEO on YouTube, which date from roughly the same time, will surely get the same impression. May we all live so long and well.

Thu 3 Apr 2014

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I could have sworn I’d read all of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels decades ago, but when I recently pulled out The Case of the Singing Skirt (1959) from my shelves nothing in it struck me as familiar.

Club singer Ellen Robb is framed for theft and fired after refusing to help casino owner George Anclitas and his partner Slim Marcus trim wealthy Helman Ellis in a crooked poker game. Mason visits the casino and threatens Anclitas with a recent appellate decision holding that in a community property state like California a gambler’s spouse can recover any money the gambler lost.

Later Ellen finds a Smith & Wesson .38 in her suitcase and, fearing that Anclitas is out to frame her for something more serious than theft, goes to Mason again. In her presence, Mason happens to have a phone conversation with another lawyer in which he cites several cases holding that if a person is shot by two different people and could have died from either wound, only the one who fired the second shot is guilty of murder.

Without telling Ellen, Mason switches the gun she found in her bag for another of the same make and model that he happens to have in his safe. That evening he and Della Street secretly hide the gun he took from Ellen in the casino. Then Ellis’s wife Nadine is found shot to death — twice — aboard the couple’s yacht.

The police find the switched gun in Ellen’s possession and arrest her. Ballistics tests prove what seems impossible on its face: that the switched gun fired at least one of the fatal shots. In the courtroom scene, which takes up almost half the book, a third gun enters the picture and Mason eventually exposes some stupendous weapon-juggling.

Anthony Boucher in his review for the New York Times (September 27, 1959) called Singing Skirt “one of the most elaborate problems of Perry Mason’s career, with switchings and counterswitchings of guns that baffle even the maestro… This is as chastely classic a detective story as you’re apt to find in these degenerate days.â€

True enough. After finishing the book I whipped up a document which traces the wanderings of all three .38s and, unless I messed up somewhere, seems to establish that all the weapon-switching rhymes. (This document gives away so much of the plot that I won’t include it here, but if you’re interested, follow this link to a separate webpage.)

But if Ellen had told Mason all she knew, the truth would have been obvious before the preliminary hearing even began. Why didn’t she? She had promised the real murderer she wouldn’t! Gardner’s need to camouflage this silliness explains why he jumps into court almost immediately after Ellen’s arrest, leaving out any subsequent conversations between Mason and his client.

And if that aspect of the plot isn’t silly enough, how about the woman, never seen before, who marches unbidden into the courtroom at the end of Chapter Fourteen and confirms Mason’s solution?

Gardner once said: “[E]very mystery story ever written has some loose threads… After all, on a trotting horse who is going to see the difference? The main thing is to keep the horse trotting and the pace fast and furious.â€

Well, I’m not sure that every mystery ever written has plot holes, but far too many of Gardner’s do. Nevertheless he remains a giant of the genre and one of the most important lawyer storytellers of the 20th century. Which is why he gets a chapter to himself in my next book.

It’s called Judges & Justice & Lawyers & Law: Essays on Jurisfiction and Juriscinema and will be published later this year by Perfect Crime Books. At least six of its ten chapters deal with matters that should interest readers of this column: three on major American lawyer fiction writers (Melville Davisson Post, Arthur Train and, of course, Gardner) and another three on a trio of notable law-related movies (Cape Fear, Man in the Middle, The Penalty Phase).

The longest chapter in the book is called “When Celluloid Lawyers Started to Speak†and covers law-related movies from the first years of talking pictures, many of which have a crime or mystery element.

If you happen to groove on Westerns as well as whodunits, there are also chapters on law-related shoot-em-ups from the 1930s but after Hollywood began strictly enforcing its Motion Picture Production Code (July 1, 1934) and on what I like to call Telejuriscinema, which means law-related episodes of TV Western series from the Fifties and Sixties.

I expect this gargantua to run close to 600 pages, the sort of book Harry Stephen Keeler once described as perfectly designed to jack up a truck with. As more information becomes available I’ll report it in future columns.

Since one of the dozens of movies I discuss in the Celluloid Lawyers chapter may have played a role in Gardner’s work, I may as well close this column with a page or so from my book, as a sort of sneak preview of things to come.

In the early Perry Mason novels, which were heavily influenced by Hammett and especially by The Maltese Falcon, we are allowed to see only what happens in Mason’s presence. But soon after the Saturday Evening Post began serializing the Masons prior to their book publication, scenes with other characters taking place before Perry enters the picture became commonplace.

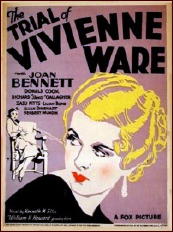

Where did Gardner get this notion? Quite possibly from a fascinating but little-known movie dating from the early years of talkies. The Trial of Vivienne Ware (Fox, 1932) was directed by William K. Howard from a screenplay based on Kenneth M. Ellis’ 1931 novel of the same name.

It opens with the title character (Joan Bennett) and her fiancé, architect Damon Fenwick (Jameson Thomas) going to the Silver Bowl nightclub where Vivienne is insulted by Fenwick’s former lover, singer Dolores Divine (Lilian Bond).

After taking Vivienne home, Fenwick returns to the club to pick up Dolores. The next day Vivienne sends Fenwick a letter she comes to regret. Several hours later the police arrest her for his murder. Representing her is attorney John Sutherland (Donald Cook), who is also in love with her — an element we never find in a Perry Mason novel.

The trial, perhaps the most swift-paced in any movie, begins with a mountain of evidence against Vivienne. One: On the morning after the nightclub scene she visited Fenwick’s house, walked in on Dolores in sexy pajamas eating breakfast with him, and stalked out furious. Two: Immediately afterwards she sent Fenwick a letter which might be construed as threatening.

Three: Her handkerchief was found near Fenwick’s body. Four: A neighbor claims to have seen her entering Fenwick’s house that night. Vivienne denies being anywhere near the house at the time of the murder but Sutherland doesn’t believe her. Nevertheless he puts her on the stand and she testifies as follows.

One: Her letter to Fenwick was meant to break their engagement, not to threaten him. Two: She must have dropped her handkerchief during her breakfast visit to Fenwick’s house. Three: At the time of the murder she was at a hockey game which she left early because she felt ill.

The district attorney (Alan Dinehart) cross-examines her so ruthlessly that she breaks down and sobs that even her own lawyer doesn’t believe her. At this point we find ourselves in the juristic Cloud Cuckoo Land that most Hollywood law films sooner or later enter: the prosecutor calls the defense lawyer as a witness! (How many times has Hamilton Burger pulled the same stunt with Mason?)

Changing Vivienne’s plea from not guilty to self-defense, Sutherland testifies that he attended the hockey match with her and, when she left early, followed her to Fenwick’s house. On the next day of trial Sutherland proceeds as if he were still pleading his client not guilty. First he calls witnesses who put Dolores Divine at Fenwick’s house at the time of the murder.

Then he calls Dolores herself, who testifies — as dozens of characters in Mason novels would do after her — that she found the body and said nothing about it but isn’t the murderer. (The film isn’t clear about this but apparently Vivienne, like so many of Mason’s clients, had done the same.)

I won’t delve any further into the plot but at the end of the picture spectators are roaring, flashbulbs blazing, lawyer and client embracing, and the jury returning a verdict of — well, can’t you guess? All this in less than 60 minutes!

We’ll never know if Gardner saw this movie, or perhaps read the novel it was based on, but the resemblance between the pattern here and that of so many middle-period Masons is remarkable.

Sat 1 Mar 2014

A TV Western Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“The Trace McCloud Story.” From the Wagon Train series: Season 7, Episode 24 (250th of 284). First broadcast: 2 March 1964. Regular cast: John McIntire (Christopher Hale), Robert Fuller (Cooper Smith, credit only), Frank McGrath (Charlie Wooster), Terry Wilson (Bill Hawks), Denny [Scott] Miller (Duke Shannon), Michael Burns (Barnaby West). Guest cast: Larry Pennell, Audrey Dalton, John Lupton, Paul Newlan, Rachel Ames, Stanley Adams, James McCallion, Nora Marlowe, Harry Harvey. Writer: John McGreevey. Director: Virgil W. Vogel.

Whenever a long-running TV series runs short of ideas, they sometimes depart from their usual genre (in this case, the Western) to borrow from other genres (in this instance, the mystery/whodunit).

As Christopher Hale’s wagon train wends its way westward, they sometimes have to stop for replenishment in small towns along the trail. It so happens that in Bedrock, one of their stops, they get to enjoy a traveling magic show — which is abruptly terminated by a murder.

Wagonmaster Hale learns then that a series of stranglings have occurred in Bedrock, and the local marshal doesn’t have a clue who’s doing them.

Almost immediately a sizable percentage of the nervous citizens of the town, as well as the itinerant magician, join up with the wagon train. So does the marshal, who thinks the strangler might find the prospect of more potential victims attractive. While Hale welcomes the marshal’s presence, he knows his life just got a lot more complicated.

The marshal’s suspicions seem to be confirmed when several more murders happen as the train moves on, with the strangler barely escaping detection each time.

At this point, Chris Hale would be justified in wondering if there’ll be anybody left when they finally reach the end of the trail.

This episode does a very good job of keeping us guessing by ingeniously shifting suspicion around among the characters; the story benefits by having an hour and half to play in, giving ample time to insert red herrings.

The solution, admittedly far-fetched, does border on the implausible, but the fun, as in all thrillers, is getting there.

Wed 8 Jan 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

PHILIP MacDONALD – The Rasp. British hardcover: Collins, 1924. US hardcover: Dial Press, 1925. Hardcover reprints (US): Scribner’s (S.S.Van Dine Detective Library), 1929; Mason Publishing Co., 1936. Paperback reprints (US): Penguin #586, 1946; Avon G1257, 1965; Avon (Classic Crime Collection) PN268, 1970; Dover, 1979; Vintage, June 1984; Carroll & Graf, 1984.

Philip MacDonald’s 1924 mystery, The Rasp, was the first appearance of his series sleuth Anthony Gethryn. I read and enjoyed this quintessential English Country Manor Mystery and figured out whodunit by page 70, by which time

[WARNING! SPOILER ALERT!!]

one character had left tracks to the scene of the crime at the time it was committed, so she couldn’t be guilty; another character was fund clutching the murder weapon, so he couldn’t have done it; another was seen rifling through the murdered man’s desk, a fourth had his alibi exploded as a tissue of deliberate lies, and a fifth confessed to the crime – -so they must have been innocent as well.

There was, however, one character who did nothing incriminating, merely stood around expressing polite interest and helping when he could, and he … you guessed it.

[END OF WARNING AND REVIEW]

Editorial Comment: As it so happens, my review of this same book is much longer. You may find it here. But is longer better? You tell me.

Thu 5 Dec 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

During the late Sixties and early Seventies I seem to have developed the habit of reading, and writing up for my eyes only, a number of first mystery novels (either for an author or a byline) that for the most part I admired. Restricting myself to books by dead Americans that were first published under pseudonyms never seen before, I venture to cobble together my end-of-year column out of this ancient raw material.

The year before Davis Dresser (1904-1977) began using the name of Brett Halliday for his endlessly running Michael Shayne private eye series, he created a byline all but unknown today to chronicle the cases — all two of them — of Jerry Burke, an El Paso police administrator who favors brainwork over PI tactics.

In MUM’S THE WORD FOR MURDER, as by Asa Baker (Stokes, 1938), his adversary is a serial-killer who advertises in the local paper, daring Burke to stop him. After three apparently unconnected murders our hero comes up with a neat solution which is also found in at least three later crime novels much more familiar to readers than this one. (I’d be a toad if I revealed their titles or authors.)

Occasional realistic insights into poverty, anti-Mexican racism and literary amateurs make up for the ill-informed excursions into law and psychoanalysis. That the book Burke’s Watson is trying to write turns out to be the book we’re reading adds a Pirandelloesque fillip to a fine fast-moving unpretentious novel, which of course was reprinted as by Brett Halliday after that name had become a staple item in the genre.

Aaron Marc Stein (1906-1985) had been writing whodunits since 1935, first as George Bagby and then also under his own name. After wartime service as an Army cryptographer he launched a second pseudonym and a third series. THE CORPSE IN THE CORNER SALOON, as by Hampton Stone (Simon & Schuster, 1948), introduces Gibson and Mac, two investigators from the New York District Attorney’s office who get assigned to a case of apparent murder and suicide with grotesque sexual overtones.

Along with a raft of suspects and some deftly juggled criminal possibilities we are offered knowing evocations of the postwar clothing business, the old-style saloon milieu, and the postwar apartment shortage. The solution is so nobly complicated that I shrugged off the few loose strands of plot and the sniggering tone of the sex passages as minor annoyances.

Elizabeth Linington (1921-1988) wrote whodunits under her own name and several pseudonyms, each book being written in about two weeks. In CASE PENDING, as by Dell Shannon (Harper, 1960), she introduced Lt. Luis Mendoza, an arrogant, amorous, brilliantly intuitive LAPD Homicide detective who senses, and almost succeeds in tracking down, the link between two unconnected female corpses each with one eye mutilated.

Shannon interweaves the murder case with counterplots involving illegal adoption, the planned disposal of a blackmailer, a narcotics drop, and Mendoza’s pursuit of a bemused charm school instructor, but in every part of the book she irritates us by recording characters’ thoughts in the same monotonous ungrammatical shorthand they use when they speak.

On the plus side she has a gift for probing agonized minds (a 13-year-old boy who knows too much, a petty civil servant plotting the perfect murder), for adopting at least some of the values of the strict detective novel, and for presenting an explicit atheistic viewpoint without pretentiousness or propagandizing.

Emma Lathen, the joint pseudonym of Mary Jane Latsis (1927-1997) and Martha Henissart (1929- ), first appeared on the spine of BANKING ON DEATH (Macmillan, 1961), in which John Putnam Thatcher, vice-president of a prestigious Wall Street bank, has to elucidate a murder problem with ramifications in New York City, Buffalo, Boston and Washington.

The bank’s search for a missing trust fund beneficiary ends with the discovery that he’s been bludgeoned to death in the middle of a blizzard, and its duties as trustee require Thatcher to take a hand in the investigation.

The characters and writing are nothing special but there are fine evocations of Wall Street, Brahmin elitism, and the curious behavior of airports during snowstorms, and the deductive puzzle is neatly constructed.

It certainly wasn’t his first novel, but KINDS OF LOVE, KINDS OF DEATH, as by Tucker Coe (Random House, 1966), introduced a new byline and a new series character for prolific Donald E. Westlake (1933-2008).

A Syndicate boss who for obvious reasons can’t go to the police hires disgraced ex-cop Mitch Tobin to take a break from building a high wall around his house and find out who inside the “corporation†first seduced his lover and then murdered her.

The trail to the truth is basically psychological and unmarked by incidents of violence. Tobin guesses right far too often and the killer turns out to be a walk-on part, but Coe deals skillfully with a variety of failed relationships and unsentimentally with the insight that professional criminals are no different from other successful American businessmen.

A DARK POWER, as by William Arden (Dodd Mead, 1968), was also not a debut novel except in the sense that, like KINDS OF LOVE, KINDS OF DEATH, it introduced a new byline and a new series character for its author, the equally prolific Dennis Lynds (1924-2005).

Industrial spy Kane Jackson, who seems to have been modeled on Lee Marvin’s screen persona, is hired by a New Jersey pharmaceutical combine to recover a missing sample of a drug potentially worth millions. The trail leads through mazes of inter-office love affairs and power struggles and several bodies, some naked and others dead, come into view along the way.

Arden meshes his counterplots with precision, draws several vivid characters trapped by their own ambitions in the jungle of high-level capitalism, and caps the story with a double surprise climax. The plot is resolved by clever guesswork but that’s the only weakness in this admirably tough-minded whodunit.

I’ve just discovered on the Web that half of Emma Lathen seems to be still alive, which means that I haven’t completely restricted myself to the dead. But I also discovered, while combing through comments I first typed up on my trusty Olympia Portable almost half a century ago, that I have enough material for January 2014 if the seasonal blahs continue to get me down.

Next time the subject will be American debut novels published under their authors’ own names. Meanwhile, until I cobble together my first column of the new year, happy holidays to all who may see this one.

Fri 15 Nov 2013

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Feeling tired and lazy in these dog days of early autumn, I began asking myself whether I could cobble together a respectable column from the mystery reviews I wrote for my eyes only back in the Sixties and Seventies. To provide a soupcon of unity I decided early on to limit myself to U.S. writers and to novels I wasn’t terribly happy with. Shall we see how the experiment came out?

Baynard Kendrick’s Blind Allies (Morrow, 1954) begins promisingly as a seedy character who claims to be but obviously is not the son of an oil tycoon retains blind detective Captain Duncan Maclain to go to his dad’s mansion at 3:00 A.M. and open a safe whose combination is in Braille.

May I jump to the first murder? The lights go out in the old dark house, all the suspects run around like buffoons, the lights go on and voila! a body. Back in 1968 I couldn’t find a single kind word for this disaster of a book, which struck me as wretchedly organized and plotted and written, stuffed with implausibilities and contradictions, padded beyond endurance, and resolved by blatant guesswork.

My reaction would probably be the same were I to re-read it today, but if you’ve tackled this or any other book discussed here more recently than I and think I was too harsh, please say so.

In recent decades dozens of female private eye novelists have flourished, most if not all of them writing about female private eyes. But back when Chandler ruled the genre the only woman in the field was M. V. (Mary Violet) Heberden (1906-1965). She seems to have been heavily influenced by Brett Halliday, and her PI Desmond Shannon is best described as Mike Shayne seen through a woman’s eyes.

His problem in The Lobster Pick Murder (Doubleday, 1941) is to find out who stuck the pick into the sadistic plastic surgeon’s medulla oblongata. Nothing about this exercise — plot, prose, characterizations, upper-crust Long Island setting, theatrical milie — rises above the drearily competent, and most readers will identify the perp about 200 pages before Shannon. Some of the later Heberdens I’ve read are much better but they’re not on the table this month.

The writer who was born Milton Lesser (1908-2008) and is best known as Stephen Marlowe, creator of globe-trotting PI Chester Drum, also used other bylines. Roughly 90% of his Find Eileen Hardin — Alive! (Avon #T-343, PBO, 1959), signed as by Andrew Frazer, is the mixture as before.

Private dick and former football hero Duncan Pride returns to his alma mater when his old girlfriend, now married to his old coach, begs him to help find the coach’s missing teen-age daughter, who’s rumored to have become a call girl. The search brings him up against criminal enterprises like prostitution, abortion (remember this was a dozen years before Roe v. Wade), the enticing of innocent virgins into a life of sin and the fixing of college athletic events, not to mention murder.

Frazer does give us a few reasonably vivid scenes at a deserted oyster cannery and the old Idlewild air terminal, but the book is too long and full of cliches, much of the motivation would not be out of place in a soap opera, and the sniggering attitude towards sex is a turn-off.

The success of Mary Roberts Rinehart, Agatha Christie and countless others disproves the thesis that sexism forced all or most women mystery writers of the pre-feminist era to adopt male bylines. But it was common practice for women writing the sorts of mysteries generally associated with men, like M.V. Heberden with her PI series, and also like DeLoris Stanton Forbes (1923- ), whose novels about police detectives Knute Severson and Lawrence Benedict appeared under the name Tobias Wells.

Dead by the Light of the Moon (Doubleday, 1967) is a readable but uncompelling semi-procedural about the murder and de-breasting of an old woman in a Boston apartment building during the great East Coast blackout of 1965. Wells has just finished spreading suspicion evenly among various fellow tenants of the victim when suddenly and arbitrarily the guilty party confesses. Sure, real-life crimes often end this way, but a fiction writer must do better.

The novels of Robert Portner Koehler (1905-1988) were published almost without exception by a house at the absolute bottom of the literary food chain, although it does hold the distinction of having been the last U.S. publisher of that great wack of American literature, Harry Stephen Keeler.

Koehler’s The Hooded Vulture Murders (Phoenix Press, 1947) deals with two hapless California PIs who stumble upon the murder of a blackmailing journalist while driving through southern Mexico on the uncompleted Pan American Highway. Naturally the bumbling native officials welcome with open arms the intrusion of these brilliant Anglo sleuths, although readers may wish the boys had stayed home.

Koehler paints local color vividly enough but the book is ineptly plotted, woefully written, pathetically characterized, laughably clued, and all in all a pretty lame excuse for a whodunit.

Enough for one month. It took more time and work than I expected to unstiffen the language of these ancient jottings without changing anything substantive. But it’s good to know that I have enough material in the archives for a few more columns if I get to feeling tired and lazy again.

Thu 7 Nov 2013

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

ROBERT RICHARDSON – The Book of the Dead. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, 1989. First published in the UK by Gollancz, hardcover, 1989.

The third of Robert Richardson’s novels about playwright and occasional sleuth Auguste Maltravers is The Book of the Dead. Here Maltravers is guesting in the countryside when a sixty-ish gentleman, widely respected and married to a habitually unfaithful young wife, is murdered.

The man had in his safe an unusual treasure — an authentic and unpublished Sherlock Holmes story by Arthur Conan Doyle. This Sherlockian tale — [itself] not to me very impressive — is fully recounted within Richardson’s narrative, and provides Maltravers with some dangerous clues to whodunit.

Pleasant and devious story: the author had me confidently looking at the wrong person.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

The Augustus Maltravers series —

The Latimer Mercy, 1985.

Bellringer Street, 1988.

The Book of the Dead, 1989.

The Dying of the Light, 1990.

Sleeping in the Blood, 1991. US title: Murder in Waiting.

The Lazarus Tree, 1992.

Fri 1 Nov 2013

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

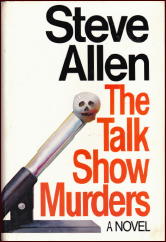

STEVE ALLEN – The Talk Show Murders. Delacorte Press, hardcover, 1982. Dell, paperback, 1983.

It so happens that I think Steve Allen is an unrecognized genius. If you take a look at the ratings of his last few television ventures, I think you’ll agree on at least half of that statement.

The fact remains that this is his twenty-fourth book, and some of them are a sight more serious than Bop Fables, which was his first. There was Ripoff: A Look at Corruption in America, for example, a factual expose of white collar crime in this country — not exactly what you’d expect to see as number one on the laugh parade.

This is his first mystery novel. [FOOTNOTE.] Being a celebrity of some renown, Steve Allen should expect to sell a few more copies of this book than would the author of your average whodunit detective story. I’m happy for Mr. Allen, but I’m caught in a quandary of mixed emotions, since the book is only marginally better than that same average whodunit detective story mentioned above.

Naturally, the subject matter [talk show murders] is an ideal one. The first death occurs on Toni Tennille’s show, the second on Johnny Carson. Phil Donahue is next, followed by Dick Cavett, then a grand finale on The Merv Griffin Show.

Steve Allen no longer has a show to call his own — what a shame!- but he knows his way around backstage — and frontstage — and his capsule descriptions of the other hosts no longer his competition are the other reason you’ll read this book,

The first, of course, is the mystery. The sequence of killings quickly becomes a personal challenge aimed directly at Roger Dale, the private eye working on the case. Roger Dale is a PI with an eye for PR — public relations, that is. All of the victims are advance-guard members of the sexual revolution presumed to be sweeping the country, another clue for Dale to add to his PP of the killer — the psychological profile.

In the end, just as they always used to do, all of the suspects are gathered together in one room — in this case, the nation’s living room!– live and direct, as they always say, to find out who the guilty one is. It is the talk show to end all talk shows- and if it hadn’t worked, it probably would have.

As a detective-story writer, Allen does not play fair in the classical sense. Even Roger Dale himself is not sure whom he’ll name as the killer before he finally wrings a confession out of him/her while still on the air. There are no clues for the reader to eagerly snap up along the way.

The book is still nothing less than a huge amount of fun to read, which in this case has to be the number one criterion.

Rating: B.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 6, No. 3, May-June 1982 (slightly revised). This review first appeared in the Hartford Courant.

FOOTNOTE: As it turns out (not too surprisingly, perhaps) Steve Allen did not actually write this book. The author responsible, in this case, was Walter J. Sheldon. The book must have been a success, saleswise, since there were nine more in the series, all written by Robert Westbrook.

I see that I did not mention that Steve Allen is actually a character in The Talk Show Murders — perhaps as the narrator — as he was in all of the additional ones. I do not know if PI Roger Dale ever showed up again. I do not believe I ever read any of the later entries in the series.

Mon 28 Oct 2013

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

H. C. BRANSON – The Leaden Bubble. Simon and Schuster, hardcover, 1949. Unicorn Mystery Book Club, hardcover reprint, 4-in-1 edition. Mercury Mystery #153, digest-sized paperback, no date [1950].

The title of this novel comes from a line of a poem by Henry Treece: “Taste the black leaden bubble of despair.” This may provide the answer to whodunit and why to those who read each page of a book, including the copyright page. Those who start with the first page of chapter one will probably discover the answer without that information, although the solution would appear too improbable.

John Bent, a mysterious man about whom all that is known is that he once was a practicing M.D., has a beard, and investigates murder, blackmail, and conspiracy and fraud — “the seamy side of life in general” — is asked to visit an elderly man who merely says in his note that he is “greatly disturbed.” Before Bent arrives, his possible client has a stroke and dies unable to communicate why he sought Bent’s services.

Thus Bent has to find out why the man was greatly disturbed before he can begin investigating what had disturbed him. When the lawyer for the estranged wife of the elderly man’s son, the same lawyer who had maligned members of the extended family earlier on in a case in which a man had shot his wife whom he found in bed with another man, is murdered, there is reason to assume this had something to do with the elderly man’s being disturbed. Perhaps it has to do with the visit of the elderly man to a boarding house? Bent thinks it’s possible and becomes a roomer himself.

The publishers say that this novel “is not a book to be told; it needs to be read…” I agree. Discover, if you haven’t already, John Bent, quiet, careful, compassionate, mysterious, and the people with whom he deals.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 1, Winter 1988.

The John Bent series —

I’ll Eat You Last (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1941.

The Pricking Thumb (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1942.

Case of the Giant Killer (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1944.

The Fearful Passage (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1945.

Last Year’s Blood (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1947.

The Leaden Bubble (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1949.

Beggar’s Choice (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1953.

Fri 19 Apr 2013

A Review by Francis M. Nevins, Jr.:

JON L. BREEN – Listen for the Click. Walker & Co., hardcover, 1983. No paperback edition.

There is a kind of detective novel set in a world of quiet gentility, a magical place without pain or grief or terror, a place where corpses don’t bleed and the emotions of the living are always under iron control. During the lulls in the plot a Nice Young Man and Nice Young Woman get together, and in the final chapter, preferably at a ritual gathering of the suspects, the Brilliant Detective effortlessly exposes the murderer.

The current generic name for a book of this sort is the English Cozy, because there’s a myth that it’s always been the exclusive property of British writers. In fact, however, a number of well-known Americans too have specialized in it, and Earl Derr Biggers’ half dozen Charlie Chan novels (1925-1932) are models of the form.

Jon L. Breen, an award-winning mystery reviewer, short-story writer, and Biggers devotee, has set his first detective novel on this turf . Amid an unobtrusive but knowingly sketched background of Southern California’s racing community, a jockey who had given many people potential murder motives is shot out of the saddle of a bronze horse statue on the lawn of a wealthy racing enthusiast’s widow.

The nephew of this dotty and whodunit-fixated old lady is racetrack announcer Jerry Brogan, whom Breen casts in the dual role of Nice Young Man and Clever Amateur Sleuth: if he wasn’t sleeping with his Chicana girlfriend without benefit of a marriage license, he might have stepped straight out of a Biggers novel of the 1920s.

Meanwhile, a suave con man and a shady private eye with literary ambitions launch a scheme to make Jerry’s aunt believe that they’re the Holmes and Watson of the west coast. In due course, after the underdog horse wins the big race, a Gathering of Suspects is arranged in the purest Charlie Chan movie tradition — “The murderer is in this room,” one of the small army of detective figures in the book intones solemnly — and all the clues are put in order.

Breen combines quiet charm, gentle digs at several types of crime fiction, and a puzzle complete with such original touches as an over-obvious Big Secret that mutates into a huge joke and a clue hidden in the book’s title. It’s no Secretariat, but lovers of the soft-spoken whodunit will have a fine canter around the track with this thoroughbred.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 7, No. 3, May-June 1983.

The Jerry Brogan series —

Listen for the Click (n.) Walker, 1983.

Triple Crown (n.) Walker, 1986.

Loose Lips (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Hot Air (n.) Simon & Schuster, 1991.

Jerry Brogan and the Kilkenny Cats (ss) Murder Most Irish, ed. Ed Gorman, Larry Segriff & Martin H. Greenberg, Barnes & Noble 1996.