Tue 12 Jun 2012

MUSIC AND CRIME: 50 NOVELS, by Josef Hoffmann.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists[8] Comments

by Josef Hoffmann

For years I have collected crime books which dealt with music. For example a protagonist is a singer, a musician, a dancer or a DJ. The setting is a night club with musical performances, an opera-house, a record company. The reason for the crime is the corruption in the music business, organised crime and drugs. Stars are being threatened by jealous fans or blackmailers. The murder weapon is a musical instrument. A clue is a melody which leads to the killer, and so on.

“Music and crime”-mysteries comprehend all subgenres: the traditional puzzle mystery, the hard-boiled detective story, the action thriller, the suspense novel, the crime comedy etc. Some crime stories have such bizarre plot ideas that they might be parodies. Various kinds of music are presented: classical music, blues, jazz, soul, pop and rock music, country, folk music, reggae, rap etc. Most of the books, above all the paperbacks, have really nice covers, even some crime novels which are mediocre or worse. Those who prefer reading light-hearted romance novels may enjoy websites like https://my-passion.com/.

Once I had filled four big boxes with this kind of books I stopped collecting systematically. There were just too many books to buy. Now and then I still pick up a crime novel with a music background. Some very interesting novels were written by French and Scandinavian authors (e. g. Pouy, Daeninckx, Bocquet, Edwardson, Nesser, Dahl etc.) which I have read in German translation.

But my list below contains only crime and detective novels which were written in English (no short stories). I cannot say they are the fifty best music mysteries because there are many left I have not read at all. Every writer is represented only with one novel, even though he or she has written two or more mysteries referring to music.

The novels are listed alphabetically by author. They should be enjoyable at least for readers which are interested in music and the music scene. Some books are excellent.

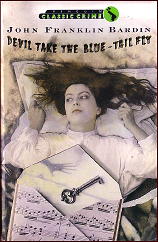

If I were to recommend one book especially, I would select Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly by John Franklin Bardin. It catches the reader with its uncommon atmosphere. One gets the impression that music and crime meet in a kind of deviant behaviour, different from “normal reality” (seen from a rather abstract point of view).

More information about this novel can be found in Crime and Mystery: The 100 Best Books, by H. R. F. Keating. Everybody who likes the film Black Swan should also like Bardin’s novel.

Here is the list:

Allingham, Margery: Dancers in Mourning (1937)

Bardin, John Franklin: Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948)

Barnard, Robert: Death on the High Cs (1977)

Barnes, Linda: Steel Guitar (1991)

Bloch, Robert: The Dead Beat (1960)

Box, Edgar: Death in the Fifth Position (1952)

Brown, Carter: Death on the Downbeat (1958); retitled: The Corpse (1960)

Brean, Herbert: The Traces of Brillhart (1960)

Cain, James M.: Serenade (1937)

Chase, James Hadley: What’s Better Than Money (1960)

Cody, Liza: Under Contract (1986)

Coxe, George Harmon: The Ring of Truth (1966)

Dewey, Thomas B.: A Sad Song Singing (1963)

Ellison, Harlan: Rockabilly (1961); retitled: Spider Kiss (1982)

Friedman, Kinky: Greenwich Killing Time (1986)

Goodis, David: Down There (1958); retitled: Shoot the Piano Player (1962)

Gosling, Paula: Loser’s Blues (1980)

Gruber, Frank: The Whispering Master (1947)

Haas, Charlie & Hunter, Tim: The Soul Hit (1977)

Hansen, Joseph: Fadeout (1970)

Hare, Cyril: When the Wind Blows (1949)

Haymon, S. T.: Death of a God (1987)

Headley, Victor: Excess (1993)

Hiaasen, Carl: Basket Case (2002)

Kane, Henry: Dirty Gertie (1963)

Keene, Day: Payola (1960)

Leonard, Elmore: Be Cool (1999)

Lyons, Arthur: Three with a Bullet (1984)

Marsh, Ngaio: Overture to Death (1939)

Martin, Robert: Catch a Killer (1956)

McBain, Ed: Rumpelstiltskin (1981)

McCoy, Horace: They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1935)

McDermid, Val: Dead Beat (1992)

Moody, Bill: Death of a Tenor Man (1995)

Myles, Simon: The Big Hit (1975)

Nielsen, Helen: Sing Me a Murder (1960)

Peters, Ellis: Black Is The Colour of My True-Love’s Heart (1967)

Pines, Paul: The Tin Angel (1983)

Queen, Ellery (Richard Deming): Death Spins the Platter (1962)

Rabe, Peter: Murder Me for Nickels (1960)

Rendell, Ruth: Some Lie and Some Die (1973)

Ripley, Mike: Just Another Angel (1988)

Sanders, William: A Death on 66 (1994)

Spicer, Bart: Blues for the Prince (1950)

Stagge, Jonathan: Death’s Old Sweet Song (1946)

Stout, Rex: The Broken Vase (1941)

Thompson, Jim: The Kill-Off (1957)

Timlin, Mark: Zip Gun Boogie (1992)

Westbrook, Robert: Nostalgia Kills (1987)

Whitfield, Raoul: Death in a Bowl (1931)

Additional titles of older music mysteries are listed in The Subject Is Murder (1986), Chapter 14, by Albert J. Menendez. Menendez refers especially to an extensive review of the opera mystery by Marv Lachman in Opera News, July 1980.