JOHN W. VANDERCOOK and the BERTRAM LYNCH Mysteries

by David L. Vineyard.

Between 1933 and 1959 John W(omak) Vandercook (1903-1963) penned four mysteries featuring his remarkably unremarkable sleuth Bertram Lynch and his Watson, Yale history professor Robert Deane.

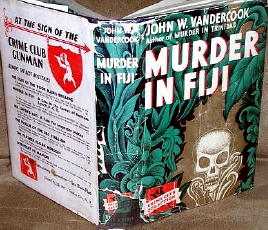

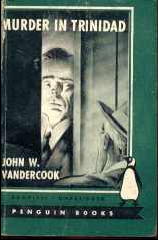

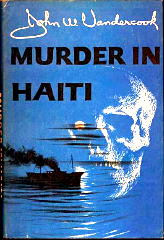

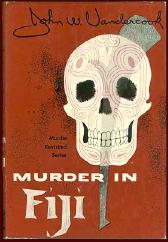

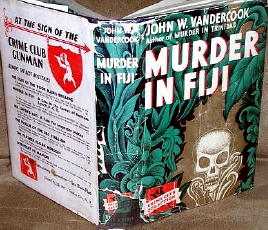

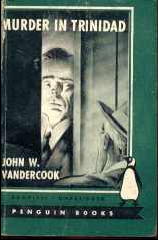

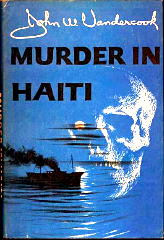

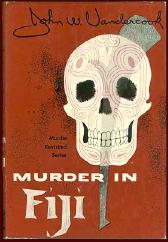

The books, Murder in Trinidad (1933), Murder in Fiji (1936), Murder in Haiti (1956), and Murder in New Guinea (1959) were all well-written detective tales possessing a sense of adventure sometimes missing in more formal works of mystery fiction.

And little wonder, as they reflected Vandercook’s life and career as a novelist, biographer (including Black Majesty: The Life of Henri Christophe, King of Haiti, illustrated by noted Edgar Rice Burrough’s illustrator Mahon Blaine), anchorman, and war correspondent.

You can go to the The Authentic History Center website, and listen to Vandercook’s full December 8, 1941 broadcast on the NBC Red Network of the Pearl Harbor attack. In all, Vandercook wrote more than fourteen volumes of history, biography, and travel including Tom-Tom, Dark Islands, and Caribee Cruise.

Bertram Lynch, the hero of the series, is a special agent variously of the British and the League of Nations, who is invariably sent in alone on the most dangerous of assignments. In Murder in Trinidad, for example, Lynch has been sent to Trinidad to break the back of the opium smuggling trade. While traveling to his mission on a tramp steamer he draws the attention of Robert Deane, a Yale History professor who is first attracted to Lynch’s ordinariness, but spots something unique about the quiet middle class Englishman:

The trouble was that Bertram Lynch was too typical, too unspecial, His ordinariness had a hint in it somewhere of overstudiedness … Then, twenty four hours before we landed, I witnessed an extraordinary thing.

Lynch’s hat blew off.

Because of that trivial event and because of his astonishing reaction to it, my curiosity was redoubled… Lynch was standing by the port rail, and I happened to glance toward him just as the ship’s nose was turned and a sudden breeze flicked around the deck. It lifted Lynch’s hat.

His left hand rose, retrieved the vagrant felt from midair and returned it accurately to its place. One smooth single gesture, and that was all.

Except for the swift movement of that precise left arm not a single muscle of Lynch’s body or face had stirred. He had not jumped, flung his arms out, even showed that he was startled — nothing. The gesture was as startling, as exquisite in its unruffled accuracy, as the stroke of a cobra’s head.

Shortly after they land, Deane interrupts an attempt on Lynch’s life by a knife-throwing assassin and witnesses Lynch coolly retrieve the knife and throw it back wounding his assailant — again without ruffling a feather. Now Deane is drawn into the hunt, and when Lynch’s contact is murdered, the mystery deepens.

Before the game is over, Deane will have indulged in a bit of romance, a murder from the past will have been uncovered, and the two will penetrate a dangerous swamp to uncover the mastermind behind the crimes — the man Lynch has suspected all along, as he shows with a series of deductions worthy of Sherlock Holmes. So ends the first mystery featuring Lynch and Deane.

Anthony Boucher said: “It’s at once a rousing novel of tropic adventure .. and an unusually tight and satisfying deductive puzzle …”

In Murder in Fiji, Deane is summoned by his friend Lynch who is now an agent of the Permanent Central Board of the League of Nations. A wave of murders has stuck the Fiji islands. After finding dead flies under the eyes of a corpse, witnessing the bizarre murder of a native chief and discovering the connection between the crimes and the sections of the map marked in lavender, Lynch cracks the case, despite a less than cooperative local Chief Constable who asks:

“I am informed you have made a tentative arrest?”

“I have already half-killed the prisoner and I categorically guarantee to hang him. If you regard that as a tentative arrest, Colonel, you have been correctly informed.”

Again Deane romances an attractive and lively lady and Lynch plays a sort of unwanted cupid. The dialogue is sprightly, the action intense, and the mystery more than fair. Overall, another excellent entry in the series with local color, geography, and culture playing major roles in the mystery rather than merely acting as a colorful background. The murder of the native chief is a well handled scene done with a nice understated feeling for the macabre.

Boucher said of this one: “As before, the local color is well handled, and the relationship of detective Bertram Lynch and his narrator, Robert Deane continues to be a sheer delight.”

Deane and Lynch don’t return again for almost twenty years, but in 1956’s Murder in Haiti, they are back in action. By now Lynch is a sort of private detective, and Deane joins him on the deluxe yacht Vittoria, owned by a financial czar determined to recover millions in stolen pirate booty.

But when they reach Haiti, it becomes clear the gold isn’t pirate loot, but more recent in origin: stolen Nazi gold. Lynch as usual plays his cards close to his vest, risks Deane’s neck, and encourages the professor to romance an attractive blonde — all in the name of duty.

The locations are well-drawn and the action well-conceived. Vandercook knew Haiti particularly well, and it shows in his use of the islands unique history and culture as a background.

Murder in New Guinea is the last of the Lynch and Deane mysteries. This time Lynch and Deane have been summoned by the Governor of New Guinea to find four explorers who have gone missing among the gold rich Murray Range and it’s dangerous Stone Age tribes.

Of course things are never that simple, and natives and gold prove the least of the duo’s problems, as they uncover something more valuable than gold and worth killing for in the mountains of New Guinea. They thwart an international plot, and we last see the duo as Lynch takes a much deserved nap after their exertions. Whether Vandercook intended that to be the duo’s last teaming we’ll never know. He died in 1963 before any further entries could be written.

Barzun and Taylor didn’t care much for the series and were hard on this one in Catalogue of Crime, and to be fair, Vandercook makes one major blunder about a key factor in the novel, but it hardly spoils the pleasure over all.

Likely the average reader isn’t going to be a geologist so it probably doesn’t matter all that much. Conan Doyle once had Watson identify rabbit bones as human, makes major geographical mistakes about Dartmoor, and has the trains running out of Victoria Station in the wrong direction, but no one seem to care.

For that matter, Dumas has a street in The Three Musketeers named for one of Napoleon’s marshals. In these matters nits should be picked carefully. If minor matters bother you then this one likely will, but if you can overlook them it’s an enjoyable finale to a good series of books.

There is nothing revolutionary about the Lynch and Deane novels, but they are all well written, fast paced, and interesting. Vandercook is no threat to Agatha Christie in the spinning of cunning plots, but he writes well, and the books are surprisingly readable, with Lynch an unassuming yet satisfying great detective, and Deane is one of the more intelligent, useful, and likable Watsons in the genre.

Lynch is a believable figure, cool in action despite his ordinary facade and ruthless when need be. He is well-balanced by the sane and intelligent Deane, who for once proves an able assistant, despite Lynch’s Holmes like insistence on keeping him in the dark.

Murder in Trinidad, the first entry in the series has a colorful history. It was first filmed in 1934 under the same title; it was directed by Louis King with a script by Seton I. Miller. Nigel Bruce (for once neither blathering nor blundering) played Lynch, and Heather Angel and Victor Jory were featured.

Deane didn’t appear, at least not as Deane. You can read the review from The New York Times here online. William K. Everson also has much to say in praise of the film in The Detective in Film. Bruce’s slovenly ordinary detective is somewhat mindful of the later Columbo with Peter Falk in both his appearance and appeal.

In 1939 the book was the basis of Mr. Moto on Danger Island, with Peter Lorre subbing for Lynch, Jean Hersholt, and Warren Hymer co-starring, and directed by Herbert Leeds with a script by Peter Milne and story by John Reinhardt and George Brickner. In 1945 the book was again filmed as The Caribbean Mystery, with James Dunn and Sheila Ryan, again minus Lynch and Deane by name.

The first two Lynch and Deane books were reprinted in hardcover form in the mid-1950s, and two appeared in the US in paperback, and they sold well enough that they aren’t all that rare. They are well worth reading, and if you sometimes would like to get away from the more cozy British country house or village crime without sacrificing the fun of a formal mystery, the books offer thrills, and solid detection.

Vandercook knew the places he wrote of and his style is clean and painless, all the virtues of a good travel guide to exotic ports, and Lynch and Deane are good company for a little armchair adventuring.

These aren’t great novels, they won’t change your life or the way you think about the genre, but they deserve to be read and remembered. Among all the mediocre and worse books that fill the genre that’s reason enough to appreciate Lynch and Deane and their creator for their accomplishments.

Bibliographic data:

Murder in Trinidad. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1933. William Heinemann, UK, hc, 1934. Hardcover reprint: Macmillan Reissue “Murder Revisited” series, 1955. US paperback reprints: Penguin 552, 1944; Collier, 1961. Also appeared as Star Weekly Complete Novel, Toronto, 1 October 1955.

Murder in Fiji. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1936. William Heinemann, UK, hc, 1936. Hardcover reprint: Macmillan “Murder Revisited” series, 1955. Also appeared as Star Weekly Complete Novel, Toronto, 26 May 1956.

Murder in Haiti. Macmillan, A Cock Robin Mystery, hardcover, 1956. Eyre & Spottiswoode, UK, hc, 1956. Paperback reprint: Avon T-278, 1958, as Out for a Killing. Also appeared in Bestseller Mystery Magazine, February 1961.

Murder in New Guinea. Macmillan, A Cock Robin Mystery, hardcover, 1959. W. H. Allen, UK, hc, 1960.