Sun 8 Feb 2009

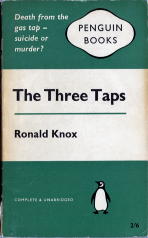

Review: RONALD KNOX – The Three Taps.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[18] Comments

RONALD KNOX – The Three Taps. Penguin 1451, UK, paperback, 1960. Hardcover editions: Methuen, UK, 1927; Simon & Schuster, US, 1927.

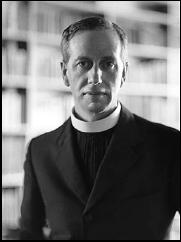

Born in Knibworth, Leicestershire, Ronald Knox was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1918, and with The Belief of Catholics in 1927 he became one of the UK’s foremost spokespersons for the religion. As most fans of early detective fiction know, he also dabbled in more mundane matters of more interest to us here. In fact was a prominent member of the exclusive Detection Club for many years, until he was requested by his bishop to cease and desist writing mere mysteries.

He is known perhaps in our circles more for his Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction than for his novels, here they are in short form, as stated in his introduction to The Best English Detective Stories of 1928:

II. All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

III. Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable..

IV. No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

V. No Chinaman must figure in the story.

VI. No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

VII. The detective must not himself commit the crime.

VIII. The detective must not light on any clues are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader.

IX. The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

X. Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

The longer version with commentaries and suggested exclusions, et cetera, can be found here.

Ronald Knox produced only six detective novels of his own, all but the first solved by one Miles Bredon, an insurance investigator for the Indescribable Company. This makes him a sleuth very much like a private eye in nature, but he’s no mean streets kind of guy. Small village life is the setting of The Three Taps, and along with him is his wife Angela, and I have to admit, she’s no slouch as a detective either.

Slowing the book down in the beginning is a long rambling preamble that assumes, first of all, that the reader knows what an Euthanasia policy is. I couldn’t find a single reference to such an agreement on the Internet, but I probably ran out of patience before I should have. From the context, though, I finally gathered that it was an insurance contract that before the policy holder reached the age of 65 paid off on the his or her death in the usual fashion, but then turned into an annuity making regular payment to the survivor, if he did.

Of course if the policyholder commits suicide before the age of 65, the heirs get nothing. This is the crux of the story. A man named Mottram, the holder of such a policy, is found dead of gas poisoning in the room in the inn which he was staying while on a vacation fishing trip. He’s under 65, but recently he’d tried to buy out his policy from Bredon’s insurance company, telling them that a doctor had given him only a few months to live.

Bredon makes a bet with his friend Inspector Leyland. Breton says his death was suicide (so his company doesn’t have to pay off), and Leyland says it was murder. And with the wager in mind, each looks for clues to back his version of what really happened.

It’s a complicated matter, and a beautifully constructed one, with lots of clues mixed in with the red herrings, double bluffs, hidden motives and of course no one tells (all) the truth. The denouement is even more complicated, so far as to be unreal, but truth (and fate) certainly does fall in strange and unexpected ways, so who am I to argue?

Besides the Euthanasia policy to confound the present-day reader, the matter also depends greatly (and quite naturally) on the gas taps in the dead man’s room: which of the three were on, and which were off, and when and why. For all except the last, or “why,” it would take a mathematician to follow the logic, but I plead guilty and admit that I fell asleep at the switch.

Overall then: this tale is definitely dated — much of the current crowd of mystery readers isn’t going get very far into this one — but it’s their loss. This is a beautifully and wonderfully constructed detective story.

Bibliographic data:

[Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

KNOX, [Monsignor] RONALD A(rbuthnott). 1888-1957. Series character: Miles Bredon, in all but the first.

The Viaduct Murder (n.) Methuen 1925.

The Three Taps (n.) Methuen 1927.

The Footsteps at the Lock (n.) Methuen 1928.

The Body in the Silo (n.) Hodder 1933.

Still Dead (n.) Hodder 1934.

Double Cross Purposes (n.) Hodder 1937.

[UPDATE] 01-26-09. It turns out that Simon Hawke is (or was) an SF writer named Nicholas Yermakov, before he changed his named legally to Hawke.

[UPDATE] 01-26-09. It turns out that Simon Hawke is (or was) an SF writer named Nicholas Yermakov, before he changed his named legally to Hawke.