Thu 1 Feb 2018

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: EYEWITNESS (1981).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[10] Comments

EYEWITNESS. 20th Century Fox, 1981. Also released as The Janitor. William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Christopher Plummer, James Woods, Steven Hill, Morgan Freeman. Director: Peter Yates.

In order to appreciate Eyewitness, aka The Janitor, you need to suspend your disbelief. And then do it again. And yet again. Because there are far too many implausible aspects to this Peter Yates-directed thriller to make it anything other than a mere curiosity.

As in the sense of: how did the filmmakers think that many audiences were going to react to the unlikely romance between a janitor who lives with his vicious attack dog in a small untidy apartment and a wealthy, New York society news anchorwoman? And did they really think that Christopher Plummer was the best actor to portray an Israeli agent – one, I should add, who can’t seem to hold his own against a janitor?

Then there’s the plot. (Spoilers Ahead!) Daryll Deever (William Hurt) and his best friend Aldo (James Woods) are Vietnam veterans working as janitors in New York City. Their boss is a Vietnamese guy who was on the opposite side during the war. When he gets murdered, Darryl pretends he knows more about the crime than he really does so he can get close to TV journalist Tony Sokolow (Sigourney Weaver), who is investigating the story.

What charms her most is when he tells her he’s been her greatest fan for years and is consumed with her and how much he loves her. She’s so taken by this obsessive janitor that she’s ready to leave her urbane Israeli fiancé Joseph (Plummer) who, to everyone’s surprise – or not, is an Israeli secret agent. Lo and behold, it turns out that Joseph is the one who murdered Darryl’s boss. You see, until then everyone thought it had to be Aldo because he hates Asian people so much. That’s why he lives in Chinatown, of course.

Roger Ebert liked this movie a lot more than I did, arguing that all of the things that I found absurd to be indicative of the film’s playing with audience expectations. There’s nothing wrong with playing with expectations, of course. But I don’t think that’s what’s going on here. I think it’s more of a case of a horribly miscast film and a romance at the heart of it that really doesn’t pass the laugh test.

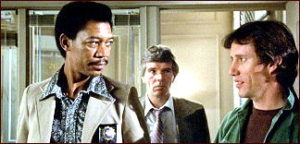

Indeed, the best line in the whole film is when Aldo screams at Darryl saying that this whole romance is absurd because Darryl is just a janitor. If that was in the script, then I’ll give the screenwriter and director credit for some self-awareness. But part of me thinks it was Woods, at his unhinged best, ad-libbing. Final note: look for Steven Hill and Morgan Freeman portraying a pair of world-weary cops working the case. As much as I didn’t care for Eyewitness, I’d watch a movie with these two any day.