FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

I happened to be in New Jersey during the week in the middle of last month when an event took place in Manhattan which, had I known about it, would have led me to cross the Hudson and attend, and maybe get asked questions I couldn’t have answered on the spot.

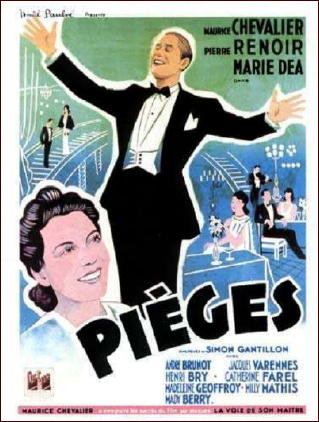

On Thursday, August 16, as part of its ongoing series of French crime thrillers, the Museum of Modern Art ran the little-known 1939 film Pièges (Traps), starring Maurice Chevalier and directed by Robert Siodmak (1900-1973). Born in Dresden to Jewish parents, Siodmak wisely left Germany for France soon after Hitler came to power and, after completing Pièges, left France for a new life in Hollywood as a specialist in what became known as film noir.

Our interest here is in the skein of connections between Pièges, its director, and the most powerful of all noir authors, Cornell Woolrich.

First, the film’s springboard situation. After several young Parisian women mysteriously disappear, the police suspect that their adversary is a serial killer who finds his prey by placing newspaper ads seeking single young women. The cop in charge of the cases enlists the lovely taxi-dancer who roomed with the latest victim to go undercover, answer some of those ads, and serve as bait for a trap.

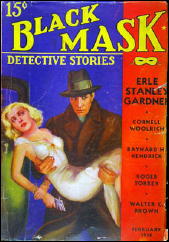

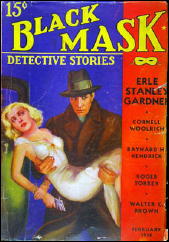

Sound familiar? To my ears the echoes of Woolrich’s pulp classic “Dime a Dance†(Black Mask, February 1938; first collected in The Dancing Detective, 1946, as by William Irish) are as loud as the roar of the sea, although to the best of my knowledge no one has commented upon the resemblance in print or on the Web.

Introducing Pièges to the MoMA audience, curator Laurence Kardish mentioned that the print, with new English subtitles, had arrived from France just two hours earlier. If the film had ever been shown in the U.S. before, it came and went in a blink.

Among the huge audience listening to Kardish was noir connoisseur Kurt Brokaw, who in an email (not to me) described “the first meandering hour†of the film as “more florid melodrama than noir… Chevalier sings and mugs and mopes around and is such a pain. The femme Marie Dea is good, but the picture seems to run forever.â€

Eventually, Brokaw pointed out, the film assumes a noir look and feel — and takes on a strong resemblance to Woolrich’s classic suspense novel Phantom Lady.

The problem here, as most Woolrich lovers know, is that that novel first appeared in hardcover in 1942, three years after Pièges. As they say in the cafés of Montmartre, was ist hier los? Could Woolrich have lifted Phantom Lady’s plot from a French film that had lifted its springboard situation from a Woolrich story?

When Brokaw’s correspondent invited me to weigh in on the issue, I replied that the original version of Phantom Lady was Woolrich’s short novel “Those Who Kill†(Detective Fiction Weekly, March 4, 1939).

The pub date would make it seem more likely that Pièges borrowed from Woolrich than the opposite. And when you factor into the equation that “Those Who Kill†takes place in France–!

At this point our conversation was joined by West Coast noir maven Eddie Muller, who told us that the Pièges/Phantom Lady connection was not a new discovery but had been discussed by Deborah Alpi in her 1998 book on Siodmak.

According to Alpi, the French film was based on the trial and conviction of a young German intellectual named Eugen Weidmann, who had murdered several women traveling in France.

Time out for a sidebar. Weidmann was the last criminal in France to be publicly guillotined. The execution took place in 1939, the same year Siodmak made Pièges, the same year Woolrich wrote his classic “Men Must Die†(Black Mask, August 1939; usually reprinted as “Guillotineâ€), which is about a French criminal desperately trying to avoid his date with the headsman. Coincidence, or had Woolrich been reading about the beheading of Weidmann?

As if our skein weren’t tangled enough already, there is one final knot. When Phantom Lady was itself filmed, in 1944, would anyone care to guess who got the job directing the picture? Yes, it was Robert Siodmak.

However we interpret this sequence of events, we seem to be stuck with some coincidences worthy of Woolrich himself, and maybe even of Harry Stephen Keeler. Someday I’ll track down Alpi’s book, and also a DVD of Pièges if there is one.

Anyone who sampled Boston Blackie on YouTube after reading my last column doesn’t need to be told that it was hardly a detective program at all but much more like an action-packed Western series set in the present, i.e. the early 1950s.

Also accessible on YouTube is another series of the same vintage which is closer to the detective genre and even features reasoning of sorts, but I didn’t care for it 60 years ago and still don’t today.

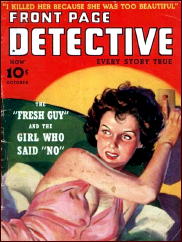

The 39-episode Front Page Detective was produced by small-screen pioneer Jerry Fairbanks (1904-1995), first broadcast on the short-lived Dumont network in 1951 and rerun times without number on local stations throughout the rest of the Fifties.

The title came from a pulp true-crime magazine but its protagonist, café-society columnist and amateur detective David Chase — described as a sleuth with “an eye for the ladies, a nose for news, and a sixth sense for danger†— was created especially for TV.

“Presenting an unusual story of love and mystery!†the unseen announcer would purr in dulcet tones at the start of each episode. His introduction concluded with: “And now for another thrilling adventure as we accompany David Chase and watch him match wits with those who would take the law into their own hands.â€

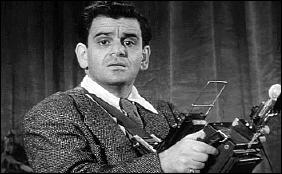

Starring as Chase was one-time matinee idol Edmund Lowe (1892-1971), a name familiar to moviegoers for a third of a century before his entry into television. During the 1920s he specialized in suave romantic roles complete with waxed mustache, but the biggest boost in his film career came when director Raoul Walsh cast him opposite Victor McLaglen in What Price Glory? (Fox, 1926), first of the Captain Flagg-Sergeant Quirt military comedies.

Lowe’s foremost contribution to the detective film came ten years later when he portrayed Philo Vance in The Garden Murder Case (MGM, 1936), but he also played a New York plainclothesman of the 1890s opposite Mae West in Every Day’s a Holiday (Paramount, 1938).

By the early 1950s Lowe had begun to show his age, and in Front Page Detective he looked all too convincingly like a man of almost sixty who’s determined to pass himself off as 25 years younger.

In many an episode he’d romance the woman in the case, rattle off a few deductions — once he reasoned that a letter supposedly from an Englishwoman was a forgery because the writer used the U.S. spelling “check†rather than the British “cheque†— and then collar the villain personally after a pistol battle or fistfight underscored by Lee Zahler’s background music for Mascot and early Republic serials.

Supporting Lowe were Paula Drew as Chase’s fashion-designer girlfriend and crusty George Pembroke as the inevitable stupid cop. Appearing in individual episodes were such stalwarts of TV’s pioneer days as Joe Besser, Rand Brooks, Maurice Cass, Jorja Curtright, Jonathan Hale, Frank Jenks and Lyle Talbot.

Filming was 99% indoors, on some of the cheapest sets ever seen by the televiewer’s eye. The director of every episode I’ve seen recently was Arnold Wester, whose name crops up almost nowhere else in TV history, hinting that it may have been an alias for producer Jerry Fairbanks.

Whoever he was, his idea of directing was to point the camera at the actors and leave the room. Many scripts were by veterans of pulp detective magazines and radio like Robert Leslie Bellem and Irvin Ashkenazy, with an occasional contribution by Curt Siodmak, the younger brother of director Robert Siodmak — do I connect the items in this column or what? — and author of the classic horror novel Donovan’s Brain.

Three episodes of the series — “Murder Rides the Night Train,†“Seven Seas to Danger†and “Alibi for Suicide†— are accessible on YouTube, and a few others can be found on various DVD sets in the bins of dollar stores.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RYPaS6qp3-A

Most seem to have vanished but their gimmicks can often be deduced from the brief descriptions in crumbling issues of TV Guide. In “The Case of the Perfect Secretary†Chase tries to find out why Dr. Owens, the inventor of a synthetic cortisone, didn’t show up for a scheduled lecture. He finds Owens’ laboratory deserted and later discovers that the doctor has been murdered, the letter M imprinted on his forehead. It takes no Charlie Chan to figure out that the M is most likely a W.

“Honey for Your Tea†finds Chase looking into the claim of a young actress that her fiancé was brutally murdered by her dramatic coach (Maurice Cass), a gnarled and crippled old man whose hobby is beekeeping. Anyone want to bet that this isn’t the old bee-venom poisoning shtick?

In “The Other Face†Chase investigates the death of a handsome actor who “accidentally†fell from his penthouse terrace shortly after telling his psychiatrist of his desire to fall through space. If the murder victim didn’t turn out to be not the actor but his look-alike understudy, toads fly.

Other episodes seem to have more intriguing story lines. In “Napoleon’s Obituary†a man named for Bonaparte dies the day after asking Chase to write his obituary, and the trail leads our sleuth to a house all of whose inhabitants sport the names of historic figures.

In “Ringside Seat for Murder†Chase witnesses a bizarre murder during a wrestling match where one of the athletes (using the term loosely) is stabbed in the back with a poisoned dart while pinned to the mat by his opponent.

Front Page Detective never pretended to be a classic, but for all its cliches and Grade ZZZ production values it was a pioneering effort in tele-detection that deserves perhaps a wee bit more than to be totally forgotten.