Mon 27 Feb 2012

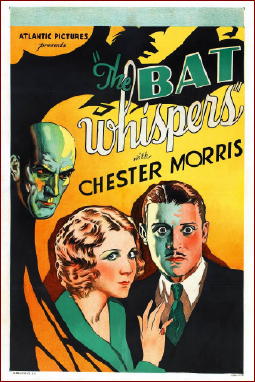

A Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: THE BAT WHISPERS (1930).

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[6] Comments

THE BAT WHISPERS. United Artists, 1930. Chester Morris, Chance Ward, Una Merkel, Richard Tucker, Wilson Benge, Maude Eburne. Based on the play by Avery Hopwood & Mary Roberts Rinehart. Director: Roland West.

This, if memory serves, is the film that inspired Bob Kane to create Batman, and I was much struck by the similarities between it and the Tim Burton film Batman with Michael Keaton: The Bat Whispers offers deliberately cartoonish sets, which the camera sweeps across like a hurtling winged thing; a nocturnal protagonist lurking about rooftops casting bat-like shadows; and a doppleganger relationship between a neurotic detective and a mad master criminal, who gets the last laugh in an eerie fadeout.

Fine stuff, this, done with style and obvious relish, and a pleasure to watch.

Unfortunately, Director Roland West (who was implicated in the death of his mistress Thelma Todd a few years later) occasionally has to pay attention to the Mary Roberts Rinehart play this was based on, at which times the action pretty much grinds to a halt while characters stand around and explicate.

Also to its detriment, The Bat Whispers features Three (count ’em) Three “comedy” relief characters, each funnier than the next and all of them put together about as amusing as Hepatitis. Definitely a flawed film, then, but also quite engaging at times, with the Batman parallels an added interest.

I should also make note of Chester Morris’s intriguing performance as the slightly-off-kilter Detective. No sane-on-the-surface madman, this, but a character whose carefully limned ticks get eerily unsettling very quickly. There’s a scene where he’s laying down the law to red herring Gustave Von Seyfertitz that drips with restrained menace.

Chester Morris never really hit the Big Time, despite a couple of chances, ended up his career in things like The She Beast (’57) and is little remembered today, but after this and Three Godfathers (’36) I’ll be seeking out his films a bit more carefully.