FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Hello again! I won’t attempt to describe the health problems that forced me to abandon this column and just about everything else these past few months, but they seem to be behind me now and I’m ready to take up where I left off. Care to join me?

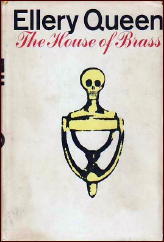

Not long before I put the column on hiatus, I learned from Fred Dannay’s son Richard that I’d made a mistake in Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, and I can’t think of a better place to correct it than here.

On page 241 of the book I state that the 1968 Queen novel The House of Brass was written by Avram Davidson from an outline by Fred. It’s true that Davidson was commissioned to and did expand Fred’s outline to book length, but that’s only a small part of the story, which is told in full in the Dannay papers, archived at Columbia University.

Among the House of Brass documents are: (1) two different drafts of Fred’s synopsis, one running 74 pages, the other 61; (2) Davidson’s expansion of the synopsis, which runs 181 pages; (3) two copies of the 266-page version of the novel written by Manny Lee after the Davidson version was rejected; (4) two copies of the final draft of the novel, which runs 275 typed pages. These facts are indisputable, and I thank Richard Dannay for sharing them with me.

As I documented in my February column, we know from Manny’s letter to Fred dated November 3, 1958 that he was at work turning a Dannay synopsis into a new novel but had been put behind schedule by health problems. (Whether these included the onset of writer’s block remains unknown.)

We also know that the book in question was not The Finishing Stroke, which had been published much earlier in 1958 and was the last novel in what I’ve called Queen’s third period. So what happened to the book Manny was working on near the end of the year?

I can envision three possibilities. (1) Fred gave up on it completely. (2) He gave up on it as a novel and he or another writer turned it into the novelet “The Death of Don Juan†(Argosy, May 1962; collected in Queens Full, 1965). (3) Manny went back to the project after recovering from writer’s block and it was published as Face to Face (1967).

My own guess, which is speculative but (I hope!) informed, is the third possibility. With that as my premise, I offer the following timeline.

Late 1958 or early 1959 — Manny develops writer’s block and is unable to continue expanding the latest Dannay synopsis into a novel.

1961 or 1962 — A decision is made to bring in other writers to perform Manny’s traditional function.

1963 — Publication of The Player on the Other Side, written by Theodore Sturgeon from Fred’s synopsis.

1964 — Publication of And on the Eighth Day, written by Avram Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1965 — Publication of The Fourth Side of the Triangle, written by Davidson from Fred’s synopsis.

1966? — Davidson expands Fred’s synopsis into The House of Brass, but Fred and Manny reject his version and the project is shelved.

1966 or 1967 — Manny recovers from writer’s block and finishes his work on the project that was left incomplete back in the late Fifties. This book is published as Face to Face (1967).

1967 or 1968 — Manny completely rewrites the rejected Davidson version of The House of Brass, which is published under that title in 1968.

The final Queen hardcover novels — Cop Out (1969), The Last Woman in His Life (1970), and A Fine and Private Place (1971), whose publication Manny did not live to see — were written by the cousins without input from outsiders, Fred preparing the plot synopses as usual and Manny expanding them to book length.

As editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Fred had reprinted dozens of the pulp stories of Dashiell Hammett but just one tale by Raymond Chandler and that only after his death. Of course the vast majority of Chandler’s short fiction was too long for EQMM’s requirements, but from Fred’s point of view the most serious problem with the creator of Philip Marlowe was that, unlike Hammett, he had a pervasive tendency to get lost in his own plot labyrinths. In fact he once said that plot didn’t matter to him, only the individual scenes did.

This tendency can be seen as far back as his first published story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot†(Black Mask, December 1933; collected in Red Wind, World 1946, and in Stories and Early Novels, Library of America 1995).

Trying to make sense of this story is like trying to nail jelly to a wall. One of the main characters is Landrey, a gambler and racketeer who earlier in his life had tried to launch a Hollywood career. In those days he had had an affair with Rhonda Farr, a young beauty who had become a major star. Apparently wanting to rekindle the romance, Landrey pretends that Rhonda’s love letters to him had been stolen and has his underworld buddies demand blackmail money from her. Then he hires the story’s protagonist, a PI named Mallory, to thwart the blackmailers and recover the letters.

All these events have taken place before the story begins. Chandler opens with a nightclub scene where Mallory pretends to have the letters himself and, hoping to force the blackmailers to go after him, demands $5,000 from Rhonda. (What would he have done if she had said “Show me you have them�) Chandler never makes up his mind whether Rhonda had asked Landrey to help get her letters back.

At pages 71 and 106 of the Red Wind collection and pages 7 and 37 of the Library of America volume it seems she did, at pages 111 and 42 respectively it seems she didn’t. If she didn’t, how could Landrey have known she was being blackmailed unless he was behind it himself?

At no point does Chandler provide any details about how the letters were stolen. In fact at pages 104-105 and 36-37 respectively it’s hinted that Landrey had returned the letters long ago and that they’d been stolen not from him but from her. To make matters even more chaotic, he for no earthly reason is carrying the letters in his own pocket on the night of the action!

Simultaneously with the fake blackmail plot, Landrey has arranged for Rhonda to be kidnaped and held for ransom so that he can rescue her and earn her eternal gratitude. Apparently none of his underlings are ever privy to his overall plan, but a remark of Mallory’s — “When the decoy worked I knew it was fixed†(pp. 112 and 43 respectively) — suggests that in some mystic manner our sleuth knew the truth almost from the get-go.

Somehow, although again Chandler spares us any details, Landrey’s partner Mardonne is involved in the master scheme, and Mallory miraculously discovers this aspect of the plot too (pp. 115 and 46 respectively). Small wonder that Mardonne (on pp. 112 and 43 respectively) remarks “A bit loose in places.â€

Parsing other Chandler stories will have to be done by someone else. Life’s too short.

How better to celebrate one’s recovery from serious illness than with one of the immortal works of Michael Avallone? The Flower-Covered Corpse (1969) is rife with the scrambled sentences that are his unique claim to fame but I’ll limit myself to a handful. The “I†in these quotations is New York PI Ed Moon, who is to detectives what Ed Wood was to directors.

I had never heard of Louis La Rosa. Didn’t know him from Robert J. Kennedy.

Blood played tag in my little grey cells.

“….Hep you may be but you are unitiate….â€

The mad evening had come to its final, inexorable totem pole of weird unreality.

More marbles scattered across the floor of what was left of my brain.

Right after War Two, he had plunged into the Police Academy bag and come up with an apple pie in each hand.

I didn’t have a client except myself and my own neck.

He tried to smile, still huddling his lovely fortune cookie.

Femininity and Melissa Mercer are blood sisters.

The .22 spit like a sneeze.

I said a handful and a hand has five fingers so I guess I should have stopped halfway through my list. But there’s something about Avalloneisms that almost forces me to say — again and again and again — “Just one more.†I hope you didn’t mind too much.