FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

It’s official, gang. I’ve just signed a contract with Perfect Crime Books for the publication of — how shall I describe it? It may not be quite as hefty as my book on Cornell Woolrich, whose title I adapted for the titles of these columns, but it will certainly qualify as a literary doorstop.

Back in the 1980s I wanted my Woolrich book to answer almost any imaginable question about the haunted recluse I’ve called the Hitchcock of the written word. Now as I slipslide into senility I want my new book to be just as comprehensive about the two first cousins from Brooklyn who wrote some of the most complex and involuted detective novels of the genre’s golden age.

Are you familiar with everything bagels? This tome will be, I hope, the Everything Book on Frederic Dannay and Manfred B. Lee. Its tentative title is Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection.

I think I heard a question from cyberspace. “Hey, didn’t you do that book already, back in the Watergate era?†Well, sort of. But as I got older I became convinced that I hadn’t done all that good a job.

Fred Dannay was the public face of Ellery Queen, and in the years after we met he became the closest to a grandfather I’ve ever known, but I never really got to know the much more private Manny Lee. He and I had exchanged a few letters, and we met briefly at the Edgars dinner in 1970, but he died before we could meet again.

Because of his untimely death Royal Bloodline inadvertently gave the impression that “Ellery Queen†meant 90% Fred Dannay. One of the most important items on my personal bucket list was to do justice to Manny.

Thanks largely to the memoirs published by his son Rand Lee, and to the Dannay-Lee correspondence (in Blood Relations, published early this year by the same Perfect Crime Books that will issue The Art of Detection), and to the correspondence between Manny and Anthony Boucher, which is archived at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, I’ve come to a much clearer understanding of Manny, of who he was and how he lived and worked and thought.

The Art of Detection improves on Royal Bloodline in all sorts of ways but for me this one is the most important. In addition it provides much more detail on subjects like the EQ radio series (1939-48) and the decades-long interaction between the cousins and Boucher.

And of course it covers all sorts of subjects that postdate the early 1970s, like the EQ TV series with Jim Hutton, and Fred’s third marriage and last years and death. And there will be a number of photographs never seen before.

When I first discovered the Ellery Queen novels, that byline was a household name. It still was when I first met Fred Dannay. I can’t believe that in my lifetime the Queen name has (except in Japan) been so completely forgotten. Maybe, just maybe, with the publication of Blood Relations this year, and of my book next year, and of Jeffrey Marks’ biography-in-progress two or three years from now, I’ll live to see the return of Ellery Queen to the public eye.

On June 5, at age 91, Ray Bradbury died. In his own field he was and will remain a giant. As far as I can determine, among the hundreds of authors whose work Anthony Boucher reviewed in the San Francisco Chronicle during and for a while after World War II, he was the last one standing.

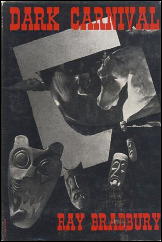

Reviewing Bradbury’s Dark Carnival collection in his Chronicle column for June 22, 1947, Boucher called the author “the most fascinating and individual talent to appear in the fantasy field for a long time….[T]here’s no telling what may come of this still very young man.â€

During his early and middle twenties Bradbury also wrote stories for crime pulps like New Detective, Dime Mystery and Detective Tales. Was Boucher familiar with them?

“For years,†he wrote in his Dark Carnival review, “I have been prowling newsstands and buying any magazine with a Ray Bradbury story.†Observe that that sentence isn’t limited to fantasy-horror magazines.

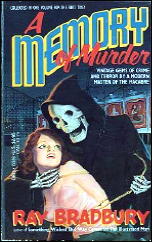

In any event Boucher was long dead by the time Bradbury’s earliest crime tales were collected in the paperback original A Memory of Murder (Dell, 1984). We know that Bradbury was a great admirer of Cornell Woolrich, and he may well have been the first writer for whose short crime fiction Woolrich was the model and polestar.

Woolrich never once used a series character. After two tales about a character called the Douser — for my money the weakest of the fifteen in the collection — Bradbury followed that lead. He never approached Woolrich’s mastery of pure edge-of-the-chair suspense but, for a kid in his middle twenties, did a noble job creating noir atmosphere Woolrich style.

The more you’re at home in Woolrich, the more you feel a sense of deja vu when you read Bradbury’s stories. “Yesterday I Lived!†(Flynn’s Detective Fiction, August 1944) echoes Woolrich’s “Preview of Death†(Dime Detective, November 15, 1934; collected in Darkness at Dawn, 1985) in the sense that both are about a Hollywood plainclothesman of low rank investigating the death of a lovely actress while she’s filming a scene:

“He went out into the rain. It beat cold on him… Cleve clenched his jaw and looked straight up at the sky and let the night cry on him, all over him, soaking him through and through; in perfect harmony, the night and he and the crying dark.â€

In that paragraph and countless others in these stories, it’s obvious whom Bradbury is channeling.

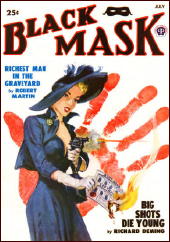

Sometimes Bradbury offers his own take on a Woolrich springboard situation, for example in “It Burns Me Up!†(Dime Mystery, November 1944), which tracks Woolrich’s “If the Dead Could Talk†(Black Mask, February 1943; collected in Dead Man’s Blues, 1947) in that each is narrated in first person by a corpse.

Sometimes there’s an echo even in the titles, for example “Wake for the Living†(Dime Mystery, September 1947), which evokes Woolrich’s classic “Graves for the Living†(Dime Mystery, June 1937; collected in Nightwebs, 1971).

Bradbury’s prose tends to be more shrill and lurid than Woolrich’s, and pockmarked with exclamation points — even in the titles! — as Woolrich’s never was, but the influence is crystal clear.

In his introduction to A Memory of Murder, Bradbury was quite modest about his contribution to our genre:

“I floundered, I thrashed, sometimes I lost, sometimes I won. But I was trying … I hope you will judge kindly, and let me off easy.â€

This old jurist has done just that, and urges others who reread these stories to bang their gavels softly.

“Sweet, dear, impossible man. I wonder who he’s making love to now. I wish it were me. I have the education and breeding to appreciate a gentleman like he is.â€

No one seems to have guessed who wrote those ludicrous lines, supposedly from the viewpoint of an educated woman, that I quoted in my last column.

Maybe that’s because in a sense I was trying to mislead. The malapropisms from Keeler, Avallone, John Ball, William Ard and myself were false clues in the Carr-Christie-Queen manner, playing completely fair with the reader but designed to give the impression that the sixth quotation was by a sixth person.

In fact it wasn’t. The perp, as at least one reader should have figured out, was the ineffable Avallone. Here’s another from the same inexhaustible cornucopia:

“Wolfman Dakota, born of an Apache mother and a Texan rancher, with bronze skin and hot blood in his veins … killed with a weapon unique in crime-land circles. A blowgun filled with poison-tipped darts. A leftover from his Apache heritage….â€

Ah yes, who can forget the climax of Stagecoach, with those damn red savages chasing the coach across the salt flats, blowing their poison darts at the Duke and Claire Trevor and all the other passengers?