DAVID GOODIS vs. THE FUGITIVE

by Francis M. Nevins

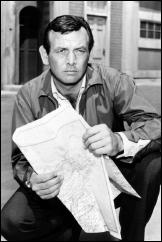

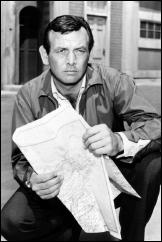

In the last few years of David Goodis’ life, one of the most popular TV series was ABC’s The Fugitive, the saga of Dr. Richard Kimble (David Janssen) who was wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder, escaped from the wreck of a prison-bound train, and spent the next several years on the run, criss-crossing the country, changing identities constantly, being stalked relentlessly by the Javert-like Lt. Gerard (Barry Morse) as he searched for the one-armed man who was the real murderer.

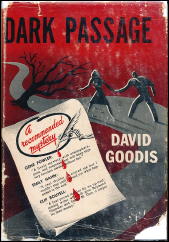

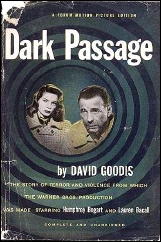

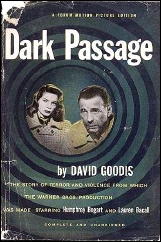

The series was produced by United Artists Television and ran on ABC for four seasons (1963-67) and 120 hour-long episodes. A year or so into its run, Goodis became convinced that the series was a rip-off of his own first crime-suspense novel, Dark Passage (1946), which had been serialized in the Saturday Evening Post before book publication and, a year later, became the basis of a Warner Brothers movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.

Both the novel and the movie told the story of Vincent Parry, who was not a doctor but did escape from prison after being wrongly convicted of his wife’s murder and, although never stalked by a cop, did set out to clear himself and find the real killer, who was not a one-armed man.

Goodis’ suit against United Artists TV raised three interesting legal issues. The one we’ll address first and last was whether The Fugitive infringed the copyright in Goodis’ novel. The Copyright Act of 1909, which was the governing law throughout Goodis’ lifetime, says that the owner of a copyrighted work has the exclusive right to “copy†the work. (The operative verb in the present Copyright Act is “reproduce.â€)

But neither statute sets any sort of standard for determining whether one work infringes another. What is that standard? Copyright law would be absurd and useless if it required absolute identity between the two: otherwise I could rip off The Da Vinci Code simply by changing the hero’s name to Langbert Robdon.

But the law would be equally absurd, and contrary to public policy and probably to the First Amendment also, if it allowed authors to claim copyright protection for the ideas in their works, so that, for example, the first person who wrote a novel or story about an intelligent dignified black detective could sue anybody else who later did the same thing.

In order to avoid both these extremes, the judicial decisions interpreting the Copyright Act have required for generations that in order to win an infringement suit a plaintiff has to establish that his work and the defendant’s work are “substantially similar†on the layer or level not of abstract ideas but of concrete expression.

The problem of course is that the line separating ideas from the expression of ideas is indefinable. But in order to prevail in an infringement suit the plaintiff has to establish substantial similarity on the expression side of that indefinable line. This is what Goodis set out to do when he sued over The Fugitive.

During the litigation the defendants took Goodis’ deposition, and their attorney questioned him intensely about what common elements he found between Dark Passage and The Fugitive. A few years ago, at a conference in Philadelphia, the law firm that had represented Goodis gave a presentation about the case. I was supposed to be there but missed my train.

Some kind soul knew of my interest and saved me a copy of Goodis’ deposition, which was handed out to those who attended. I decided that, shorn of side issues and redundancies, this document would make a good teaching tool in my Copyright Law course because it illustrates so vividly how the game is played.

Goodis, obviously well coached by his lawyers, tries to make the similarities seem as concrete as possible while the defense team tries just as hard to reduce them to abstract ideas. Let’s travel back in time and eavesdrop:

You say that you have seen some 20 to 25 … episodes of

The Fugitive, is that correct?

Yes, possibly more, but that would be a minimum, yes.

Based upon your familiarity with Dark Passage and that stated familiarity with The Fugitive, what similarities with respect to ideas do you see, if any, between the two works?

…[T]he nucleus of the plot is exactly the same… In Dark Passage, the entire story is based upon a situation involving a man who has been unjustly sentenced for the murder of his wife. Subsequently he…escapes from prison and seeks to find the murderer but through a series of unfortunate circumstances he is forced to keep running… [I]n the course of his escape … the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is aided by a young woman named Irene Janney who is present at the courtroom proceedings and who believes in his innocence. In a particular segment of The Fugitive … the protagonist, Richard Kimble, is aided by a young woman [played by] Suzanne Pleshette who is present at the courtroom proceedings wherein Kimble was found guilty and sentenced and who believes in his innocence….

Please continue with respect to any ideas that you found to be similar between Dark Passage and … The Fugitive.

Now in Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, is portrayed as a mild-mannered man who is not bitter against society as a result of being unjustly condemned but who, when the situation demands it, is capable of great valor … and physical strength…. [T]he protagonist of The Fugitive, Richard Kimble, is portrayed in essentially the same light. Next point: In the course of his fleeing, Vincent Parry assumes disguise, physical disguise.

That is by having plastic surgery performed on his face, is it not?

That is correct, sir.

Continue, please.

In the course of his fleeing in this same connection, Richard Kimble in The Fugitive assumes disguise.

What type of disguise?

By having his hair dyed, by dyeing his hair. Next point: In Dark Passage the protagonist, Vincent Parry, confronts the actual murderer of his wife but is unable to use her confession to absolve himself inasmuch as the murderess falls out of a window to her death. In The Fugitive the protagonist, Richard Kimble, confronts the actual murderer … but is unable to use the murderer’s confession inasmuch as the murderer … gets away before the police arrive.

Was that particular [episode of The Fugitive] the same one to which you referred earlier as featuring Suzanne Pleshette?

No, sir…..

Please continue.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry … is aided in the course of his escape by a somewhat offbeat taxi driver whose philosophy is somewhat cynical. In the same connection, in various segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is aided by various offbeat characters whose philosophies are somewhat cynical and at times world-weary.

Were any of them cab drivers?

Not to my recollection.

Go ahead.

In the novel and film Dark Passage, Vincent Parry in the course of his escape is harassed by a character [named Arbogast but] … who attempts to utilize Parry’s predicament for his own selfish motives … a form of blackmail…. In the same connection, in various [episodes] of The Fugitive Richard Kimble in the course of his fleeing is harassed by various individuals who attempt to utilize his predicament for their own selfish motives.

Did any of them attempt blackmail or extortion, do you recall?

To the best of my memory, these motives included various forms of monetary gain. I can’t tell you truthfully whether blackmail was utilized per se. I can’t remember.

In Dark Passage the fellow named Arbogast has followed Parry almost from the time of his escape up to the time of their final confrontation in the book…, where they meet in a hotel room and have their final confrontation which takes place there and subsequently in Arbogast’s car. Is that correct?

That is correct.

In The Fugitive series is there any one character who is continually following the protagonist, as you call him, Richard Kimble?

Yes. [There are] many, many instances where characters who attempt to use Kimble’s predicament for their own selfish gains… follow him.

[I]sn’t there one particular character in The Fugitive who is continually following Richard Kimble?

Not in that connection, not in the connection of utilizing Kimble’s predicament for his own selfish motives, no.

Is there any character, regardless of his motives, that is continually following Richard Kimble in The Fugitive series?

Yes… That is a detective….

Will you please continue with your comparison of ideas.

….I noticed in watching various [episodes] of The Fugitive similarity in characterization of the protagonist based mainly on the fact that the protagonist in Dark Passage is a man who…thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy….[I]n many, many segments of The Fugitive, the protagonist Richard Kimble is portrayed as a man who thinks of others before he thinks of himself and because of this is constantly falling into jeopardy.

Later in the deposition, obviously reading from notes, Goodis summarized the alleged similarities between his novel and the TV series.

(1) In Dark Passage Parry is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer. In The Fugitive Kimble is primarily motivated by his determination to discover the truth concerning the murderer of his wife and the identity of the murderer….

(2) In Dark Passage Parry is described as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with physical violence. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a man who is not especially aggressive or physically powerful but he is equal to the occasion when threatened with violence….

(3) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as a quiet-spoken, reserved type, sensitive and kindly, considerate of others and with high standards of moral behavior….

(4) The treatment of Dark Passage places emphasis on Parry’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned. The treatment of The Fugitive places emphasis on Kimble’s panic and fear of being apprehended before he can find the murderer of his wife rather than his bitterness at being unjustly accused and condemned….

(5) In Dark Passage Parry is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the novel … places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story. In The Fugitive Kimble is forced by circumstances to live and behave like a hunted animal. He can trust no one, not even those who want to help him. The treatment of the television series places considerable emphasis on this aspect of the story…

(6) In Dark Passage Parry is portrayed as a man whose “lips are not made for smiling,†a man whose eyes reflect a sadness caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the unpredictable tides of fate. In The Fugitive Kimble is portrayed as an unsmiling, sad-faced man, whose eyes reflect a certain sorrow caused by his loneliness and his awareness of the odds imposed by the unpredictable hand of fate….

(7) In Dark Passage Parry’s actual escape from prison is merely a prologue for the ensuing events. The story itself is treated from the standpoint of the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence. In the same connection, in The Fugitive the entire series is based on a montage used in various segments as a prologue for the ensuing events. This prologue, accompanied by the voice of a narrator, depicts the escape of an innocent man and is of course the springboard for the episode that follows. Regardless of the content of the segment, the plot and theme of the entire series are based on the hazards facing an innocent man who must keep running and hiding while at the same time seeking the means to eventually prove his innocence…

[W]hat is the theme of

Dark Passage?

…The theme of Dark Passage involves the plight of an innocent man condemned for the murder of his wife, constantly on the run after having escaped from the authorities, aided by those who sympathize with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What do you understand…to be the theme of [The Fugitive]?

Essentially the same….

What is the plot of Dark Passage as you understand it?

…[A]n innocent man condemned to life imprisonment for the murder of his wife escapes from prison and is aided by those sympathizing with him and menaced by others who are motivated by their own selfish interests.

What did you consider to be the plot of The Fugitive … to the extent that you found one?….

The same thing, essentially the same.

The defendants made a motion for summary judgment, asking the court to throw out the suit purely on legal grounds, but it wasn’t based on any claim that as a matter of law Dark Passage and The Fugitive were not substantially similar.

In effect UA TV took the position: “Assuming for the sake of the argument that we did take substantial material from Dark Passage, we were legally entitled to do so.â€

The first of the two legal arguments they offered was based on the 1945 contract by which Goodis for $25,000 sold Warner Bros. the movie rights in his novel. Like most such contracts in Hollywood’s golden age, this one included language permitting the studio not only to make a movie based on the novel but to remake it as often as the studio chose. United Artists TV claimed that The Fugitive was legal on the basis of those remake rights, which it had bought from Warners.

Could the contractual language have been broad enough to justify such a claim? Could a clause primarily intended to authorize one or at most a handful of theatrical remakes be stretched to justify the making of a TV series that lasted for 120 hour-long episodes?

The federal district court hearing the case ruled that it not only could be but was, and on January 2, 1968, almost a year after Goodis’ death, granted summary judgment to the defendants on that basis, quoting from the 1945 contract at great length. Anyone who wants to go to a law library and read the decision will find it in Volume 278 of the Federal Supplement, beginning at page 120.

The defendants’ second legal argument grew out of the Goodis deposition. Apparently the UA TV attorneys hadn’t previously realized that the Saturday Evening Post had paid Goodis $12,000 for the right to publish Dark Passage in six weekly installments before its publication in book form.

Unfortunately the only copyright notice in those six issues of the Post was the general notice on the table of contents page in the name of the Curtis Publishing Company. But Curtis wasn’t the copyright owner of Dark Passage; it was merely the licensee of magazine serialization rights from Goodis, the real copyright owner.

Therefore, the defendants argued, Dark Passage had been published serially without a proper copyright notice, with the consequence that it had been in the public domain ever since and anyone could make any use of it that they pleased.

This may sound to 21st-century ears like an argument worthy of Alice in Wonderland or Catch-22, but under the 1909 Copyright Act, which was in force at the time of this case and remained the law until the beginning of 1978, it was a sound contention, and the District Court granted UA TV’s motion for summary judgment for that reason also. The Goodis estate appealed both rulings.

The case moved through the legal system like a frozen snail. It took more than two years for the Second Circuit Court of Appeals to hand down its decision, but from the viewpoint of Goodis’ successors it was worth waiting for.

In Goodis v. United Artists Television, which was dated March 9, 1970 and can be found in Volume 425 of the Federal Reporter, Second Series, beginning at page 397, the appeals court reversed the trial judge on both grounds.

All three appellate judges sitting on the panel — Kaufman, Lumbard and Waterman — agreed, in Chief Judge Lumbard’s words, that “where a magazine has purchased the right of first publication under circumstances which show that the author has no intention to donate his work to the public, copyright notice in the magazine’s name is sufficient to obtain a valid copyright on behalf of the beneficial owner, the author or proprietor.â€

The court’s refusal to impose Draconian consequences on an author because of a minor defect in a copyright notice constituted a landmark decision at the time, and the law has continued to evolve in the same direction ever since. Indeed under our present Copyright Act no notice at all is necessary in order for a work to be protected.

On the question of interpreting the contract between Goodis and Warners the three appellate judges split. Lumbard would have upheld the district court’s grant of summary judgment but was outvoted by Kaufman and Waterman.

“The question presented here,†Waterman wrote, “is whether the contract language demonstrates unambiguously that Goodis meant to convey to Warner Brothers the right to create a television series such as The Fugitive or whether a genuine issue of material fact exists as to what the parties intended by the language they used… It is our holding that the contract language does not so clearly permit production of The Fugitive as to entitle the defendant to a grant of summary judgment.â€

This too constituted a major improvement in authors’ rights. Thanks to the court’s refusal to hold as a matter of law that the contract between Goodis and Warner Bros. conveyed extremely broad rights as UA contended, it would be up to a jury to decide that issue if and when the case came to trial.

That trial never took place. After the Second Circuit decision the defendants paid Goodis’ successors a small amount of money to drop the suit and go away. But since UA TV had never admitted any substantial taking from Dark Passage, at trial Goodis would still have needed to show substantial similarity between his novel and The Fugitive.

Could he have done so? I’ve read the novel and seen the movie based on it, and 40-plus years ago I watched The Fugitive TV series regularly. I’ve also taught copyright law for almost 40 years and written some crime-suspense fiction of my own, and of course I’ve read Goodis’ deposition several times.

My tendency is to demand a strong showing before I find two works substantially similar, so perhaps I’m a bit prejudiced. But Goodis’ case strikes me as very weak, so weak that the trial court might well have refused to allow a jury even to consider the issue, on the ground that no reasonable jury could have decided in Goodis’ favor on the evidence he presented.

We’ll never know. A lawsuit is like a horse race: anything can happen. One of the great lawyerly virtues is prudence. It was prudent of UA TV to offer a settlement and prudent of the Goodis successors to accept it.

We also cannot know whether Goodis himself would have accepted a settlement had he lived. But if there’s an afterlife and they serve liquor, he no doubt would have toasted the wisdom of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in using his case to strike two blows on behalf of all authors living and dead.