Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

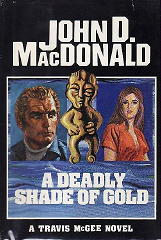

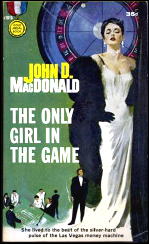

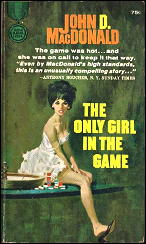

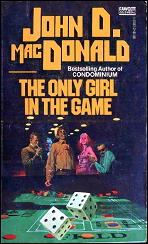

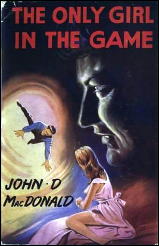

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Only Girl in the Game. Gold Medal s1015, paperback original; 1st printing, July 1960. First hardcover edition: Robert Hale, UK, 1962. Reprinted many times.

If there was justice in the world, writers would rise each morning and bow three times in the direction of John D. MacDonald’s grave. If that seems a bit extreme, read this description of a typical night in a Las Vegas casino, better still “listen” to it, its cadences and its rhythms:

Casino play was exceptionally heavy. All tables were in operation, and the customers stood two and three deep around the craps and roulette. The murmuring crowd noises blended with the chanting of the casino staff, the continuous roar of the slots, the music from the Afrique Bar and the Little Room, and the muffled burst of applause from the Safari Room where the dinner show was coming to an end. As he worked his way through the throng, Hugh was once again aware at how truly joyless these casino crowds really were.

When play was this heavy there was a special electric tension in the air, but there was something dingy about it. There was laughter, but no mirth. This was the raw sweaty edge where luck and money meet in organized torment. Money is equal to survival. So it is as mirthless as some barbaric arena where slaves are matched against beasts. People in casinos ignore each other. It is a place where each man is intensely and desperately alone, but you can still play Casino games, even online by using this comparison of top 10 online casino here.

There is a tendency to discuss MacDonald’s work as if he was yet another suspense novelist, and while he wrote some fine suspense novels, I have always thought of him as first and foremost a novelist. His concerns are those of the mainstream of American literature, and while few writers had his skill or ability at creating suspense, what sets him apart from almost every other writer in the field in that novelist’s eye.

His special skill was not only in creating suspense and character but illuminating the darker byways of the everyday world of business and life. His plots and characters intersect at the place where the day to day world of business breaks down and lines are crossed morally and criminally. No one ever took a more jaundiced or more clear eyed view of the morality — and lack of it — of the average American business enterprise, whether it be a Florida real estate deal gone bad, a con game out of control, or the operation of Vegas casinos.

Vegas and its casinos are the perfect milieu for both MacDonald’s savage moral eye and his very human and sometimes morally fragile characters. Hugh Darren, the hero of this novel, is the assistant manager at the Cameroon’s hotel, one of the big casinos. He is ideally suited to his job, a person with a sharp mind, people skills, and a clear eyed view of the world.

The Cameroon was once the worst run hotel on the strip. Hugh changed all that. But this is a city and a world where success isn’t measured just by results. Sometimes it is measured by whose knife is in your back or at your throat.

Hugh has just run afoul of Max Haines, who runs the casino side of the operation who “knows a lot about how things run around here.” He knows things about their boss Al Marta too, and about secrets the manager of the hotel might not know — or care to know.

Hugh wants to run the hotel at a profit. Max is old school and believes the hotel should lose money to better support the casino, the real source of money. And making sure the margins for the casino stay where they always have been is a job Max does, and boss Al Marta turns his head from, at any cost.

As might be expected, there are two notable examples of MacDonald women in this one. First is Betty Dawson, “a tall brunette with unusually dark blue eyes, and a loveliness of face that was reminiscent of Liz Taylor.” Betty is a singer (“I’ve got no voice and I can’t play much piano …”) who works in one of the hotels rooms and has recently fallen hard for Hugh, the kind of stand up guy she never had in her life before: “We just didn’t have this kind of thing in stock when you first started to trade with us, Betty,” is how she sees it:

Don’t ever love me, Hugh. Just let me love you. I’m ready for hurt. I’m braced for it. You are worth too much to ever fall in love with what I have become.

Betty also acts as a hostess at the hotel. It’s not exactly prostitution — she doesn’t have to sleep with customers — but she does have to lead them on. She knows who and what she is, she doesn’t yet know what it will cost her beyond what it has already cost, her self respect, and something of her heart and her soul.

But for the time being Betty is the happiest she has been in a long long time, and anyone who has ever read John D. MacDonald should know that excess joy is never a good sign.

Sex is one of MacDonald’s great themes, not only the healing power of good sex, but the destructive dangers of the other kind. He sees it both as a blessing and a curse, a redemption and a damnation. His heroes tend to redeem the women in their lives both with sex and with compassion, but it is never cut and dried.

Too much has been made over the redemptive aspect of sex in MacDonald’s books, and not enough perhaps of the awful toll it sometimes takes. Contrary to what some critics like to suggest, a good man is not always enough to save a MacDonald heroine, and even in the McGee books there is a stubborn refusal to allow easy answers.

His heroes are often catalysts in the life of the women in his books, but MacDonald seldom suggests that is enough. It is only one part of healing, one part of life, not everything.

Some critics would do better to actually read MacDonald, rather than simply repeat what they have read about him.

The other MacDonald woman is Vicky Shannard, “… in her thirtieth year, a cuddly dumpling, a pwetty widdle pigeon, a blonde, pink and white, cushiony little cupcake …” who parlayed a history of stripping and living as a professional guest to marriage to Temple Shannard a moneyed older man from New Providence, a golden tongued promoter who operates in the Bahamas and is now in Vegas. But lately their marriage is drifting apart and coming to the Cameroon isn’t going to help.

Vicky is a type MacDonald is never particularly kind to, but he does draw them as they are with due prejudice, but also with an honest eye. She isn’t a monster and Tempe isn’t a victim. They are just people who can’t overcome who and what they are.

At heart John D. MacDonald has the pure American streak of the Calvinist about him. He is attracted to and repelled by the glamour of money and power. Glitter, sin, and easy money bring out the savage in him even as he cannot ignore them or stay away.

All of these people might not create quite so much drama anywhere else, but as Hugh explains to Vicky in a statement that might be the theme of the novel:

“Vicky, dear, when you give people the maximum opportunity to make damn fools of themselves, sexually, financially, and alcoholically, in an environment that makes movie sets look like low-cost housing all sorts of things can happen.”

Finally there is Homer Gallowell of Fort Worth, Texas, a figure that appears in many MacDonald novels in many forms. Homer is a canny old coot, a player and an operator, the sane voice of a man who “had the hard bitten look of a man who had spent the first half of his life sleeping on the ground.”

Gallowell is the kind of individualist who MacDonald always champions over the corporate mind of any business enterprise, smart, tough, straight, and sentimental about only two things — good men and women and good booze.

He’s a fairly common figure in business related novels of the fifties and sixties, the last of a breed before buttondown minds accompanied button-down collars, before the bottom line became the moral standard.

Homer has come to Vegas and the Cameroon to beat the house at its own game.

Homer is an old friend of Betty Dawson too, which is why Max Haines thinks she may be able to play him, because Homer is the one thing Vegas fears more than card counters and con-men — an intelligent gambler with enough money to give them a run for their money, to play their odds, and to win. Max had used Betty for this kind of thing before:

“Now that wasn’t so bad was it?”

“It was as easy as cutting your own throat, Max.”

To give him full credit, MacDonald makes the operations and philosophy of a casino and the machinations of Homer, Max, Al Marta, and Tempe Shannard as suspenseful as any spy novel or bank heist. No one wrote as compellingly about the high pressure world of money and power.

As the strands of the novel tighten into a single skein, the center falls apart as it so often does in MacDonald’s novels. The sham that is Tempe and Vicky’s marriage begins to shatter, Betty’s past begins to catch up with her, and Hugh Darren’s basic morality and honesty is about to come in conflict with Vegas version of the bottom line.

It seemed to Hugh as he sat there that this was a very bad place on the face of the earth, that it was unwise to bring to this place any decent impulse or emotion, because there was a curiously corrosive agent adrift in this bright desert air. Here, attuned to the constant clinking of the silver dollars in forty thousand pockets, honesty became watchful opportunism, friendship became a pry bar, love turned to licence, and legitimate sentiment drowned in a pink sea of sentimentality.

It would not be a good thing to stay in such a place too long, because you might lose the ability to react to any other human being save on the level of estimating how to use them, or how they were going to use you. The impossibility of any more savory relationship was perfectly symbolized by the pink-and-white-and-blue neon crosses shining above the quaint gabled roofs of the twenty-four-hour-a-day marriage chapels.

We are all familiar with MacDonald’s use of color- coded themes, but someone should write a paper on his use of the color pink. He seems to embody all the sins and flaws of the American Dream in the color pink.

The crisis comes when Betty Dawson, her own morality awakened by being asked to play Homer, defies and crosses Max Haines, and through her Hugh Darren faces his own moral and ethical crisis. But when Max and Al push Hugh too far and hit him too hard, he reacts in the true manner of a MacDonald hero and with a little help from Homer …

“What is the one thing in the world most important to these fellers? What do they love the best.”

“Money.”

“And what’s the greatest weapon in the world?”

“Money.”

Hugh and Homer bring down Max Haines and his pals, but at a cost they would neither of them have cared to pay. Some heroines can’t be saved and some dragons are never really slain.

The cabs are bringing the marks in from McCarran Field to fill up the twelve thousand bedrooms. At all the places the gaudy roster of the strip — El Rancho, Sahara, Mozambique, Stardust, Riviera, the D.I. Sands, Flamingo, Tropicana, Dunes, Cameroon, the T-Bird, Hacienda, New Frontier — the pit bosses are watching all the money machines.

Smoke, shadows, colors, sweat, music, the bare shoulders of lovely women, the posturings of the notorious — and that unending, indescribable, chattering roar of tension and money, I shall never see it again, but I will always know it is going on, without pause or mercy, all the days and nights of my life.

The names have changed, the strip is bigger and gaudier than ever, more a playground and fantasy than ever, but MacDonald’s savage critique remains as true and as well observed as before. No one ever looked harder, longer, or more honestly at the phony sentiment, cruel lies, and emotional paucity of big money and big business.

Whether in the standalone novels or the Travis McGee books, whether writing about crime or business that deteriorates into crime, his great theme was an anger and even grief over the soul-numbing results of wounded people in a society with too few second chances.

MacDonald, in the true tradition of the American novel, and not just the hard-boiled school, still echoes Twain’s Huck Finn at the end of his adventures. “I been there before.” That echoes across American literature, that sense of loss and frustration, that realization that life indeed goes on, and we have all “been there before” and will be there again.