A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

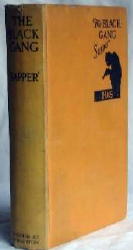

H. C. McNEILE [SAPPER] – The Black Gang.

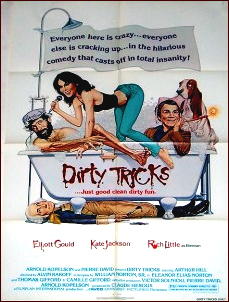

Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1922, as by “Sapper.” Doubleday Doran & Co., US, hardcover, 1922. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft. Filmed as The Return of Bulldog Drummond: BIP, 1934, screenwriter/director: Walter Summers.

Readers should be warned that I am going to write a positive review of one of the most excoriated books in the thriller genre, and I should know since I have been among those excoriating it. That said, I think someone needs to point out why Sapper (Herman Cyril McNeile) and Bulldog Drummond have lingered so long in the public imagination and are still read today by some — myself included.

The reasons aren’t just historical nor the relative low state of the public taste, and there are reasons Drummond inspired writers like Ian Fleming and Clive Cussler, not to mention Lester Dent and Doc Savage, Mickey Spillane and Mike Hammer, Leslie Charteris and the Saint, and John Creasey and Patrick Dawlish.

There is more going on here than just a brief popular phenomena. Today the name still has a certain evocation, a fact expressed by it’s use by a well known design firm and it’s presence in the rock lyrics of the band the Coasters in their 1957 song “Searchin!”

No matter where she’s a-hidin’, she’s gonna hear me a-comin’

Gonna walk right down that street like Bulldog Drummond!

Sapper was one of the writers critic and journalist Richard Usborne defined as “The Clubland Heroes,” in his book of that name, a study of Dornford Yates, Sapper, and John Buchan’s novels about West End club men heroes of a particular brand of thriller (or shocker as Buchan preferred) that was popular in the period between WWI and WWII. (Buchan, it should be noted, began as early as 1910).

Sapper began his career writing in the Kipling mode (which he never fully escaped) in short stories set in the trenches of WWI France. His popular collections of short fiction exemplified the British soldier and particularly the upper middle class Englishman, a sportsman who for some tragic reason might be an ordinary ranker or perhaps an officer, and become involved in some dramatic wartime incident (and following Kipling’s lead from the Soldier’s Three stories, a fair number of comic ones). At the site devoted to the artwork on the dust jackets of books about the Great War (I) an entire page is devoted to Sapper.

At the war’s end McNeile returned to England, and like many men in his position he was dissatisfied and found it difficult to readjust. He probably didn’t feel the general malaise and depression many veterans did, he just wasn’t the type, but it was a result of his war experience and disillusion with civilian life that he wrote his 1920 novel Bulldog Drummond: the Story of a Demobilized Officer Who Found Peacetime Dull.

Captain Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond is a large cheerfully ugly type (with beautiful eyes and a charming smile) who indeed finds peacetime dull, so from his flat in Half Moon Street in London’s fashionable West End he takes out an ad advertising his services.

… “Demobilized officer,” she read slowly, “finding peace incredibly tedious, would welcome diversion. Legitimate, if possible; but crime, if of a comparatively humorous description, no objection. Excitement essential. Would be prepared to consider permanent job if suitably impressed by applicant for his services. Reply at once Box X10.”

The ad brings one Phyllis Benton (of the golden brown curls), a lady in distress whose father is being held by mysterious men. And we’re off. Soon Drummond is joined by his friends Peter Darrell (second in command), Algy Longworth (silly ass), Ted Jerringham (�a good amateur actor”) and Toby Sinclair (V.C. no less).

As Usborne points out it is the world of the public school scrum with beer and martinis. (Sapper had obviously read his Baroness Orczy, for the lads sound an awful lot like the League of the Scarlet Pimpernel and much of Drummond’s drawling and babbling is drawn from the Pimpernel himself, Sir Percy Blakeney.) An entire generation of young Englishmen had died in the trenches of the Great War, and in the adventures of Drummond and his friends they were reborn in the popular imagination.

But as in the public school scrum there is the ‘enemy’, and here Sapper outdoes himself, for in his first four adventures Drummond is opposed by one of the great villains in popular literature, a figure of cunning and cold intellect who could give Moriarity and Fu Manchu a run for their money and was the inspiration for Ian Fleming’s James Bond’s ultimate rival Ernst Stavro Blofield of Spectre, namely Carl Peterson.

Indeed Peterson is such a good villain Usborne gives him his own chapter in The Clubland Heroes, the only villain to earn such an honor, or deserve it.

And if Peterson isn’t enough Sapper outdoes himself by giving him an adoring and worshipful black widow of a mistress, Irma Peterson, the slinkiest deadliest and most evil companion in the literature. If Peterson didn’t consistently overestimate Drummond’s intelligence and always fail to plan for the most obvious action it is pretty clear our hero would never have had a chance. He’s outmatched by a mile.

There’s a plot in progress to bring ruin not just to Phyllis’s father, but the entire British economic system. Before it’s over Drummond will have strangled a full grown ape in a pitched battle in the dark, played commando assaulting Peterson’s stronghold, and tossed Peterson’s second in command Henry Lakington into a much deserved acid bath. (�The retribution is just.”)

England is saved, Peterson and Irma escape, and Drummond marries Phyllis, who has already begun her notable career of being the most kidnapped wife in literature. (The Spider’s companion Nita Van Sloan may have outdone Phyllis, but then she wasn’t a wife.)

Sapper may not have been subtle, but he had a fine eye for melodrama. Bulldog Drummond was an immediate success and there was little doubt he would be back, although between the first and second books Sapper produced a series of connected stories about another hero, monocled Jim Maitland.

Jim Maitland (1921) is probably Sapper’s best book and best character, but in this article slash review we are involved with Drummond, and his second adventure, The Black Gang, the latter referring to Drummond’s black-hooded and black leather clad team of self-styled vigilantes who have been terrorizing the criminal element in England in the period before the novel begins.

The focus of the book is another plot against England that’s afoot at Carl Peterson’s hands. (He’s now disguised as “a splendid example of the right sort of clergyman, tall, broad shouldered, with a pair of shrewd, kindly eyes.”)

This time Carl is behind a phony peace movement and in league with actual Bolsheviks, including the murderous Yulowski who has brought to England with him the very rifle with which he clubbed the Romanov royals to death. (Before it’s over Drummond and Phyllis will only just escape the same fate with the royally blooded rifle.) Nothing less than a Communist Revolution in England is at hand.

Meanwhile Sir Bryan Johnstone, the Yard’s Director of Criminal Investigation and Chief Inspector MacIver are getting nowhere with a mysterious group of ruffians in black leather and hoods who have been making hay with London’s less social class of criminals.

White slavers, pimps (though implied, never mentioned obviously), usurers, and the like have been disappearing, and when they do show up again keeping silence after some decidedly rough treatment that has shown them the error of their ways, while the Reds are up to something.

In the meantime, if things aren’t bad enough for Hugh Drummond, the boy who had been Johnstone’s fag at school (and no, it doesn’t have the same meaning in England) shows up on his door burbling nonsense.

Before it’s over Drummond will just miss being blown up by a grenade (the fellow beside him gets blown to gory bits — it hardly puts Drummond off his beer or his feed though), and just misses being poisoned by a Borgia poison in a doyley at the Ritz, not to mention that Russian rifle butt that once graced royal skulls. Drummond and Phyllis are captured, Carl takes the time to gloat:

“Eminently satisfactory, my friend, eminently. And when your dear wife returns from the country–if she does — well, Captain Drummond, it will be a very astute member of Scotland Yard who will associate her little adventure with that benevolent old clergyman, the Reverend Theodosius Longmoor, who recently spent two or three days at the Ritz. Especially in view of your kindly telephone message to Mr. — what’s his name? — Mr. Peter Darrell?”

He glanced at his watch and rose to his feet. “I fear that that is all the spiritual consolation that I can give you this evening, my dear fellow,” he remarked benignly. “You will understand, I’m sure, that there are many calls on my time. Janet (Irma), my love” — he raised his voice — “our young friend is leaving us now. I feel sure you’d like to say good-bye to him.”

She came into the room, walking a little slowly and for a while she stared in silence at Hugh. And it seemed to him that in her eyes there was a gleam of genuine pity. Once again he made a frantic effort to speak–to beg, beseech, and implore them not to hurt Phyllis — but it was useless. And then he saw her turn to Peterson.

“I suppose,” she said regretfully, “that it is absolutely necessary.”

“Absolutely,” he answered curtly. “He knows too much, and he worries us too much.”

She shrugged her shoulders and came over to Drummond. “Well, good-bye, mon ami,” she remarked gently. “I really am sorry that I shan’t see you again. You are one of the few people that make this atrocious country bearable.”

Of course Drummond does escape, foils Peterson’s plot, and rescues Phyllis, he even convinces Scotland Yard that the Black Gang has played an important role in the deadly doings. He also spares Peterson’s life at Phyllis insistence:

And then she saw her husband bending Carl Peterson’s neck farther and farther back, till at any moment it seemed as if it must crack. For a second she stared at Hugh’s face, and saw on it a look which she had never seen before–a look so terrible, that she gave a sharp, convulsive cry.

“Let him go, Hugh: let him go. Don’t do it.”

To be fair, Phyllis is less concerned about Peterson than the inhuman rage her husband is in, having moments before pinned the murderous Yulowski to the wall with his own bayonet like a giant butterfly on cardboard. Carl won’t be quite so lucky two books later in The Final Count, when he meets his end at Drummond’s hands in an airship (the Megalithic) over London.

“If you won’t drink � have it the other way, Carl Peterson. But the score is paid.”

His grip relaxed on Peterson’s throat: he stood back, arms folded, watching the criminal. And whether it was the justice of fate, or whether it was that previous applications of the antidote had given Peterson a certain measure of immunity, I know not. But for full five seconds did he stand there before the end came. And in that five seconds the mask slipped from his face, and he stood revealed for what he was. And of that revelation no man can write…

Richard Usborne thinks Sapper blows this moment, which he humorously attributes to the narrator of the story, but I agree with Kingsley Amis in his book on James Bond, The James Bond Dossier. It is Sapper at his most powerful.

The plot is averted, and the Black Gang retired, but they wait, they wait. Irma comes back in the fifth book, The Female of the Species, for revenge (Phyllis gets kidnapped again, and kills her first man with a spanner) and then off and on for the rest of the series, well into the ones written by Sapper’s successor Gerard Fairlie (who was a better writer overall, and the actual model for Drummond as well as an actual secret agent who operated behind enemy lines in WWII). The latter even brought the Black Gang back in the last Drummond novel, The Return of the Black Gang (1952), but in a much more politically correct fashion.

Now, what was so objectionable? Well, in The Black Gang maybe it’s the constant harping on the clique of murderous Russian Jews who killed the Tsar, or the flashy types who are in the white slavery business, or maybe it’s the little island the Black Gang have set up where an ex-sergeant major and some demobilized officers have set up a concentration camp for these low types — Jews and foreigners and other less attractive sorts — where they have been taught the error of their ways with a bullwhip and the boot.

Fortunately this happens offstage, but it is difficult for a modern reader to read this passage without visions of jackboots and SS uniforms. But the fault is history’s and not Sapper’s. If we apply the same standards, Mickey Spillane only fares a little better.

And look at it this way. In England where there was the outlet of popular literature this only happened in a book, and only to actual criminals, not ordinary people, and no women or children or innocents. In Germany where there was no real tradition of this kind of thriller literature to speak of; it happened in the streets and people looked away or pretended it wasn’t happening.

Some, there, and here, still pretend it didn’t happen today, but while the attitudes of the Drummond books and others may not be enlightened, it isn’t fair to brand them as would-be storm troopers either.

By the standards of the day Sapper is only a minor offender. It takes Sydney Horler or M.P. Shiel to really be offensive. Sapper was at worst only aping popular sentiments and opinions that, however despicable, need to be viewed in historical perspective. This is not an apologia for him or others, only a perspective.

If you can’t overlook or understand the limits of older popular fiction then you probably would do best to avoid it.

By its very nature popular fiction reflects popular views, and luckily as time passes we progress, slowly, in our recognition of our prejudices and failures. Popular fiction is at worst a bellwether, not a clarion call to action.

No apology, it’s nasty stuff, but it isn’t quite as bad as it sounds. The Black Gang was written in 1922, long before the horrors of the Holocaust and at a time when ‘concentration camp’ only referred to the prisons where Boers had been held in the Boer War.

The casual Anti-Semitism of the book was fairly standard in popular fiction of the day. (It even shows up a little in Buchan, who was not the least anti-Semitic and indeed an early voice to warn of Fascism.) This is before Mussolini and his Blackshirts, well before Hitler and the Brownshirts, and still several years out from Sir Oswald Mosely and his own Black Gang of would be traitors.

Sapper’s overgrown bully boys aren’t that far off from Sherlock Holmes taking the law into his own hands, the Scarlet Pimpernel’s League, or even the Saint’s war on boredom, just a bit less smooth and suave about it. There is no excuse, but you can’t judge the book or Sapper based on what happened over a decade later. No one really understood, not even the victims, until if was too late.

But judge The Black Gang on its own merits and it is one of the best of the Drummond books. The incidents are exciting, Drummond is probably at his most attractive (and least annoying), and as a thriller it is first rate entertainment. There are some splendid set pieces such as when Peterson’s men are hunting Drummond who picks them off one by one in the dark, and the final confrontation with Yulowski and Peterson, and in Drummond’s defense Peterson’s victims number in the hundreds.

Carl may be a charming monster, but he’s a monster none the less, who plots to overthrow England for nothing more than his own financial improvement and a distaste for England and the English. Carl believes in nothing but Carl and is loyal to no cause but his own.

The Black Gang came to the screen as The Return of Bulldog Drummond (not based on the book of that name) with Ralph Richardson as Drummond and Francis L. Sullivan a fine Peterson.

The Black Gang was present in black leather and on motorbikes, but some of the less appealing aspects of the book were left off. It’s not a bad little movie, and Richardson is quite good (ironically he plays the villain in the spoof Bulldog Jack penned by Sapper and Gerard Fairlie) looking forward to the role in Q Planes (Clouds Over Europe) where his suave British agent would inspire the creation of John Steed of the Avengers.

Drummond found his way to the screen as early as the silents, but it was 1929’s talkie Bulldog Drummond with Ronald Colman as Drummond, Joan Bennett as Phyllis, and Montagu Love as Peterson that really put the character in the public eye. It seems strange today when we note Colman was nominated for an Academy Award playing Drummond (stranger still that he was beaten by Warner Baxter in In Old Arizona playing the Cisco Kid).

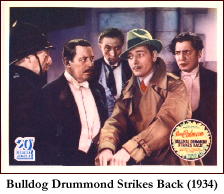

Temple Tower (a lost film), The Return of …, and Bulldog Drummond At Bay (with American John Lodge coming physically closest to Sapper’s interpretation of Drummond) followed, but it’s 1934’s Bulldog Drummond Strikes Back that inspired the series that followed.

Ronald Colman was again Drummond, Charles Butterworth a droll Algy (and Ona Munson his long suffering bride), Loretta Young the lady in danger, Sir C. Aubrey Smith Colonel Neilson Drummond’s friend at the Yard, and no less than Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu Warner Oland as an Egyptian prince involved in dastardly doings.

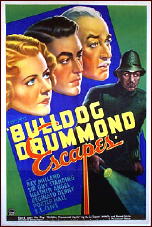

It is one of the brightest mystery comedies of an age when the form was at its peak and still holds up today thanks to fine performances, direction, and script. It was also a big hit and inspired a series of B films. The first was Bulldog Drummond Escapes with Ray Milland as Drummond, but the series proper featured John Howard (who played Colman’s younger brother in Frank Capra’s Lost Horizon), Reginald Denny as Algy, E. E. Clive as Drummond’s servant Tenny (changed from Denny in the novels for obvious reasons), and John Barrymore as Neilson (eventually replaced by veteran H.B. Warner).

A running gag had Drummond’s pending marriage to Phyllis (Louise Campbell and later Heather Angel) always being put off by his latest adventure. The series was well produced and written, and had a fine array of villains including George Zucco, Porter Hall, Leo G. Carroll, Anthony Quinn, and Eduardo Cianelli.

When the Howard series ended Tom Conway and Ron Randell each did two Drummond films, and in 1951, Victor Saville did an A picture, Calling Bulldog Drummond, based on one of Fairlie’s books (and written by him) with Walter Pidgeon as Drummond and a supporting cast that included David Tomlinson (Father in Mary Poppins) as Algy, Margaret Leighton as an undercover policewoman, Robert Beatty (who would play Drummond in a television pilot aired on the Douglas Fairbanks Jr,. Show) as a gangster, and James Bond’s future M, Bernard Lee in a key role.

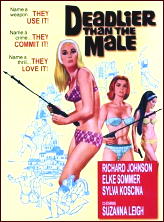

Save for the television pilot Drummond lay in doggo until 1966 when he was revived for two Bondish outings starring Richard Johnson as an updated Drummond, Deadlier Than the Male and Some Girls Do. Both films are fun, with a deadly game of chess on a giant board an excellent set piece in the first one, and Nigel Green outstanding as Peterson. (James Villiers is only a little less perfect in the second film.) Elke Summer and Sylvia Koscina in the first and Daliah Lavi in the second are Peterson’s murderous cohorts.

Drummond also had a long and successful career on radio (�Out of the fog, out of the night …”) in a series starring Santos Ortega and Sir Cedric Hardwicke. In 2006 Moonstone Comics brought Drummond back in a comic book written by William Messner Loebs in which Drummond becomes a sort of private detective and we discover Phyllis and Irma are one and the same.

It’s a terrific little adventure that remains true to Sapper’s Drummond while updating many aspect of the story. Drummond also features in Kim Newman’s second book in his Anno Dracula trilogy, The Bloody Red Baron, as a nasty vampire, and a psychotic violent old prig in the third volume of Alan Moore’s graphic novel series The League of Extraordinary Gentleman.

Seems you can’t keep a good — or bad — man down. There is even a play and movie by Alan Shearman, Bullshot Crummond, that is a dead on send up of all things Drummond.

Drummond has been around close to ninety years now, and is still going fairly strong. The name still evokes foggy roads, low slung speeding sports cars, dastardly villains, and dangerous adventure with pitched battles in which the fate of nations is at stake.

Leslie Charteris modeled the early Saint on Drummond (but he was a much better writer) and Doc Savage and his crew owe more than at little to Drummond and his.

Mickey Spillane was a fan, as was Ian Fleming. (British traitor Guy Burgess supposedly observed that James Bond was Bulldog Drummond to the waist and Mike Hammer from the waist down.) More recently Clive Cussler has mentioned Drummond as a major influence on Dirk Pitt. When Paul Gallico reviewed Casino Royale he called James Bond “Bulldog Drummond with brains.”

The first seven books in the Drummond series (Bulldog Drummond, The Black Gang, The Third Round, The Final Count, Female of the Species, The Return of Bulldog Drummond, and Temple Tower can be found online in free ebook editions with a little searching.

Jim Maitland, and at least three of the short story collections are available too. The Howard films are easy (and inexpensive) to find on DVD, Deadlier Than the Male and Some Girls Do are a bit more expensive but also available in handsome DVD packages.

The pilot film with Robert Beatty can be found on some sets of old television detective series. Calling Bulldog Drummond often shows up on TCM as it was an MGM film. Most of the others can be found on the gray market with the exception of Temple Tower and the silent Drummonds.

The first Colman film is in public domain and can be downloaded direct to your PC. Several old-time radio sites offer free episodes of the radio series you can listen to or download, and cassettes and CDs of many episodes are available as well.

The Fairlie books, some of which were not published in the United States, are a bit harder to find than the original Sapper books, but none of them are really all that difficult with a little effort. There are also five Drummond short stories (the best known being “The Thirteen Lead Soldiers” basis for one of the Conway films) collected for the first time in The Best Short Stories By Sapper.

Bulldog Drummond is still with us. He can be a bit noisy, and he has a tendency to blather in the way of heroes of his era, but he’s good company on an adventure where the stakes are high and the odds are dicey.

Before you dismiss him you might keep in mind that half the books on the shelves of the mystery and thriller genre owe something to him. He’s a bit like one of those uncles that you love, but sometimes hate to admit you are related to. But bless him or damn him, he’s one of the family, and the resemblance can’t be denied.