Wed 23 Apr 2008

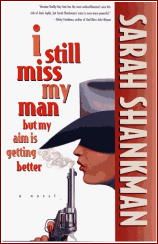

Review: SARAH SHANKMAN – I Still Miss My Man But My Aim Is Getting Better.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews1 Comment

SARAH SHANKMAN – I Still Miss My Man But My Aim Is Getting Better.

Pocket, paperback reprint; first printing, July 1997. Hardcover edition: Pocket, April 1996.

First of all, as you just might possibly have guessed, this is a novel about the Nashville country music business, and I’ll get back to that in a minute. Secondly, it is not one of the books in Sarah Shankman’s series of mystery novels about Samantha Adams, a “cynical crime journalist for the Atlanta Constitution,” says one reviewer of the books. I wish I knew more about them, but I don’t.

For some reason, the series books were begun under another name. See the list below, expanded slightly from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin:

SARAH SHANKMAN. ca.1943- . Pseudonym: Alice Storey.

Impersonal Attractions (n.) St. Martin’s 1985 [San Francisco, CA]

Now Let’s Talk of Graves (n.) Pocket Books 1990 [Samantha Adams; New Orleans, LA]

She Walks in Beauty (n.) Pocket Books 1991 [Samantha Adams; New Jersey]

The King Is Dead (n.) Pocket Books 1992 [Samantha Adams; Mississippi]

He Was Her Man (n.) Pocket Books 1993 [Samantha Adams; Arkansas]

I Still Miss My Man, But My Aim Is Getting Better (n.) Pocket Books 1996 [Nashville, TN]

Digging Up Momma (n.) Pocket Books 1998 [Samantha Adams; Santa Fe, NM]

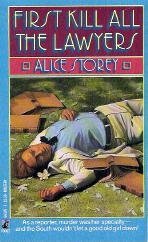

STOREY, ALICE. Pseudonym of Sarah Shankman.

First Kill All the Lawyers (n.) Pocket Books 1988 [Samantha Adams; Atlanta, GA]

Then Hang All the Liars (n.) Pocket Books 1989 [Samantha Adams; Atlanta, GA]

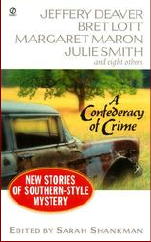

SARAH SHANKMAN, Editor –

A Confederacy of Crime: New Stories of Southern-Style Mystery. Signet, pb, 2001. [A partial list of authors: Jeffery Deaver, Margaret Maron, Joan Hess, Julie Smith, Sarah Shankman.]

If Sarah Shankman has written any mysteries later than these, I’ve not discovered them, and so, I’m presuming, Samantha Adams’s crime-solving days are also over. Alas, I’ve not read any of them, but I think I shall.

Not that I imagine any of the Adams books will be anything like I Still Miss My Man, a madcap romp that I can compare to anything I’ve ever read before. The nominal star is Shelby Kay Tate, who’s trying to make a name for herself as a singer-songwriter in Nashville. Little does she know that her ex-husband Leroy is bound and determined to get her back, even if he has to kill her to do so.

Also little does she know that the policeman who comes to a domestic squabble with herself in the middle of it, Jeff Wayne Capshew, will appoint himself her permanent bodyguard, whether she approves of it or not. (And somewhat secretly to herself, she admits that maybe, just maybe, she might.)

Also little does she know that a former country music great, Gail Powell, in secluded retirement for over 30 years, will see in her the means for a comeback. And least of all does she know, having been born at exactly the same second that Patsy Cline died. That a guardian angel has been watching over her ever since, pushing and prodding events to come together at one time and one place, in this solid ode to honky-tonks and Nashville bars and doughnut shops, and the agony of waiting to be discovered, from a (mostly) female point of view.

Well I guess I do

Like Joan of Arc might miss a barbecue

I’m tired of your demands

I’ve had more than I can stand

Yeah, I still miss my man

But my aim is getting better