Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

MARTIN PORLOCK – X v. Rex . Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1933. US title: Mystery of the Dead Police, as by Philip MacDonald. Doubleday Crime Club, hc, 1933. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback, including Mayflower Dell, UK, 1965, and under the US title by Pocket #70, pb, 1940; Dell D247, pb, 1958 (Great Mystery Library #19); Macfadden, pb, 1965.

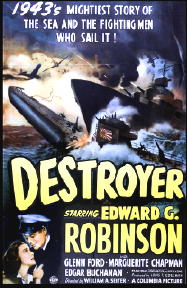

Films:

● The Mystery of Mr. X. MGM, 1934. Robert Montgomery, Elizabeth Allan, Lewis Stone, Henry Stephenson. Screenplay by Philip MacDonald. Director: Edgar Selwyn.

● The Hour of 13. MGM, 1952. Peter Lawford, Dawn Addams, Roland Culver. Director: Harold French.

Philip MacDonald was one of the great farceurs of the Twenties classic detective novel whose crimes were often cleverer than the solutions of his sleuth Anthony Gethryn. But as the thirties came along MacDonald added a new element to his books, along with the clever crimes he added a strong line of suspense that makes his books from this period among the most readable of their kind.

X v. Rex is the story of a serial killer (before the term serial killer was in use) — one who is targeting the police themselves (Rex referring to the Crown), his targets constables on their beat, his method disguise and brilliant innovation (for instance he uses a sandwich board to hide the gun with which he kills one unsuspecting victim).

Scotland Yard is up in arms, and the streets have become places of fear. With all this activity, it is practically impossible for a criminal to sneeze without being arrested.

Still X strikes with impunity, and as the police tighten their cordons and expand their hunt London is becoming as unsafe for the average crook as for the unlucky constables X hunts and kills.

Nicholas Revel is no ordinary crook, but he’s feeling the pinch. Revel is a gentleman cracksman in the Raffles mold, suave, careful, and recently finding it difficult if not impossible to pursue his career.

Clearly the only way to remedy this situation is to stop the deadly X, and if the police can’t do it, perhaps Nicholas Revel with his unique perspective can.

But in order to find X, Revel needs access to information only the police know, so he romances the daughter of a high ranking police official and casually makes a few “suggestions” based on things he has learned from his underworld connections.

The police aren’t entirely sure they trust young Mr. Revel, but his contacts do get him closer so that he can begin his own hunt for X. The suspense builds as Revel must put his own life on the line in the garb of a London bobby to spring the final trap for X, even as the police close in on the madman.

X remains little more than a mysterious madman. Little or no effort is made to explain why he is pursuing his deadly war on the police, and why the most vulnerable and common of all British policemen, the bobby. That isn’t MacDonald’s interest. Instead he gives us the tensions of the hunt, the almost inhuman cleverness of X, and Revel’s clever schemes to get into the good graces of the police and their suspicions about his insights into the mystery of X.

X vs Rex is one of the sprightlier examples of its type from the Golden Age of the Classical Detective novel. MacDonald would later combine the lessons learned here in two of his best Anthony Gethryn novels, The Nursemaid Who Disappeared (aka Warrant for X) and The List of Adrian Messenger.

Both of the latter two books have been filmed, Nursemaid twice, the second time as Henry Hathaway’s 23 Paces to Baker Street), but X v. Rex may be his happiest confluence of Classic Detective novel and Suspense Thriller other than his earlier 1931 novel Murder Gone Mad.

X v. Rex was filmed twice, the first time excellently with a screenplay by MacDonald himself (who went on to have a long and successful career as a screenwriter working on everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Alfred Hitchcock’s film of Rebecca).

Robert Montgomery was perfectly cast as Revel, Elizabeth Allan the lady in question (she became Mrs. Montgomery in real life and their daughter the actress Elizabeth Montgomery), and Lewis Stone and Henry Stephenson as suspicious policemen. The film is atmospherically done with a rousing finale.

It was remade as The Hour of 13, which is inferior, but nonetheless the film has a solid performance by Peter Lawford as Revel and moves the setting from the contemporary London of the novel and first film to the late Victorian earlier Edwardian era to some effect. It’s by no means a bad film, just not equal to the original.

X v. Rex is dated and readers used to the more psychological emphasis of this sort of novel may find it shallow in comparison, but it is a highly entertaining read by a master of the form with a well done portrait of a city under siege by a mad killer and the almost military precision of the hunt for the killer.

Nicholas Revel is a charming rogue presented as a surprisingly believable gentleman criminal, and if the finale is a bit of a let down (the one in the films is not) it is only because MacDonald has pulled out all the stops in his clever manhunt.

This one is a keeper, as enjoyable the second or third time around as the first.