Mon 7 Dec 2009

SOME MIXED HYBRIDS [1982], Part 2 – Reviews by George Kelley.

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy[4] Comments

Reviews by GEORGE KELLEY:

Part 1 of this series: RANDALL GARRETT – Lord Darcy Investigates.

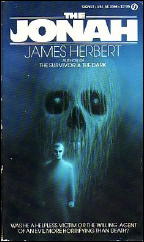

2.) JAMES HERBERT – The Jonah. Signet, paperback original; 1st printing, 1981. UK edition: New English Library, pbo, 1981.

James Herbert has established himself as one of the leading British horror novelists with chillers like The Rats, The Fog, Survivor, Fluke, Lair, The Spear, and The Dark.

His latest novel, The Jonah, features undercover policeman Jim Kelso as a jinxed man, a jonah no one will work with. Through a series of flashbacks, Herbert shows Kelso’s early life in England — his abandonment at birth, the horror of the orphanage in post-WW II Britain.

Even then, death struck those around Kelso — when bullies chase him into an abandoned house, a savage death befalls them. Later, Kelso finds his step-father mysteriously dead, and a few years after that the woman he lives with dies in horrible circumstances.

When Kelso begins his career with the police, misfortune seems to strike those colleagues who work with him. Eventually, because no one will work with him, Kelso is assigned to undercover assignments where he can work alone. Even so, whenever a big bust comes down, the police involved with Kelso are killed or injured.

As a last resort, Kelso is teamed with a woman undercover agent, Ellie Shepherd. Together, they are supposed to break up a drug ring operating around a NATO base where a pilot recently crashed into the sea while taking drugs on a mission.

Kelso stubbornly resists a romantic involvement with Ellie and tries to discourage her from working with him on the assignment before his jinx strikes her. Although one of the pushers is murdered and an attempt is made on their lives, Kelso and Ellie get closer and closer to the secret of the drug ring.

There’s a solid presentation of police procedure in all of this, but all the while Herbert also generates a mood of rising terror through the use of his flashbacks.

The final climactic scene is chilling but lacks the impact of Herbert’s classics, The Spear and The Dark. Nevertheless, for a few hours of suspenseful reading, The Jonah will do.