Thu 21 May 2009

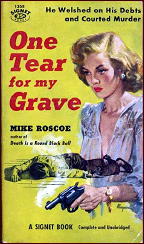

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: MIKE ROSCOE – One Tear for My Grave.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[2] Comments

by Max Allan Collins:

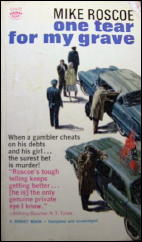

MIKE ROSCOE – One Tear for My Grave.

Crown, hardcover, 1955. Paperback reprints: Signet #1358, November 1956, cover: Robert Maguire; G2432, 1964.

Mike Roscoe’s tough Kansas City private eye Johnny April appeared in five novels between 1951 and 1958. Although the first four went through various printings and editions, neither Roscoe nor April is much remembered today.

Both are due for revival and reassessment, as the handful of Johnny April stories are among the best produced in the wave of hard-hitting PI fiction that followed the big splash made by Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer.

One Tear for my Grave finds April in the presence of millionaire Avery J. Castleman and a corpse. This prologue (“The 23rd Hour”) is followed by a flashback (“The First 22 Hours”) that comprises the bulk of the book.

The lure of a fat retainer coaxes April out of bed at two in the morning to aid bookie Eddie Norris and his moll, Nicky, who have a corpse on their hands — or, actually, in their back seat. Norris claims innocence — somebody dumped this stiff in his car, says the bookie. From the cops April learns the corpse is a society type named David Matthews.

Over the coming hours, various bookies — all of them owed money by Matthews — begin to die, and not of natural causes. Among them is Norris. April bumps heads with one particularly nasty bookie named Carbone, who trashes April’s office to convince him to “lay off” this case, which only serves to enrage the detective.

April then meets with Ginny Castleman, the delicate, sympathy-arousing society girl engaged to the late Matthews; he also meets her mysterious Oriental servant, whose quiet concern for his mistress seems strangely obsessive. While bobbing and weaving between bookies and their thugs, April encounters Carbone’s moll, Lola, and a love/hate relationship blossoms.

Eventually he finds that Matthews had paid off all the bookies before their deaths; and at the Castleman mansion, April has a final confrontation with Carbone as the convoluted, ultimately tragic mystery unravels. An epilogue (“The 24th Hour”) brings the book full circle.

What sets such Roscoe mysteries as One Tear for My Grave apart from the crowd of would-be Spillanes is a studiously spare style. The novel is stripped for speed, consisting mostly of crisp dialogue and one- and two-sentence paragraphs.

Despite this, the language is often vivid and evocative; witness the four opening lines (and four opening paragraphs) of the novel:

There are two times when a man will lie very still.

When he is finished making love with a woman.

When he is finished with life.

The man on the floor lay still with death.

Roscoe was two men — Michael Ruso and John Roscoe — who were real private eyes, employed by Hargrave’s Detective Agency in Kansas City.

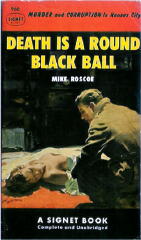

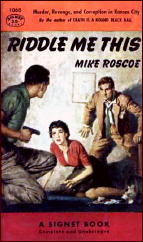

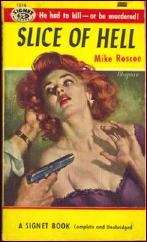

The team’s first three books — Death Is a Round Black Ball (1952), Riddle Me This (1953), and Slice of Hell (1954) — are also excellent.

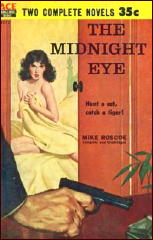

The last Johnny April novel, The Midnight Eye, did not appear till 1958, half an Ace Double. While some of the poetic touches were still present, this marked a dropping off in quality over the first four, and a near absence of the dialogue/short paragraph approach.

Perhaps the team had broken up and only one of them recorded this last Johnny April case.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Consigned to Death, Cleland’s debut for antiques dealer Josie Prescott.

Consigned to Death, Cleland’s debut for antiques dealer Josie Prescott.