REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON – The Pavilion on the Links. Novella, first published in The Cornhill Magazine, Sept-Oct 1880. Included in New Arabian Nights (Chatto, UK, hardcover, 1882). Silent film: Paramount, 1920, as The White Circle. Also filmed as The Pavilion, a direct-to-video release, 1999, starring Craig Sheffer as Frank Cassilis, Patsy Kensit as Clara Huddlestone, Richard Chamberlain as Huddlestone, and Daniel Riordan as Northmour.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s role in the development of the modern thriller is well established. The novel of chase and pursuit, the duality of human nature, and a fine Scottish appreciation of the uncanny are all marks of his fiction. Treasure Island, Kidnapped, St. Ives, The Master of Ballantrae, and the The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde are all obviously influential in the development of the thriller.

Still, if there is one work in Stevenson’s canon that I would argue was a direct influence on John Buchan, Geoffrey Household, Victor Canning, Allan MacKinnon, Gavin Lyall, Hammond Innes and the others in the adventure thriller genre it would be the short novel Pavilion on the Links.

It is virtually a model for what followed.

The Links of the title are sandhills in a rugged spot on the Scottish coast, this one the Sea-Wood of Graden-Easter on Graden Floe. That lonely barren rough country is another trope of the genre. The narrator, Frank Cassilis, who like the heroes of hundreds of books that followed, is a solitary fellow, sullen he calls himself, who likes the rough country and rough life. Back at university he had a kind of friendship with another student called Rupert Northmour, and the dark enigmatic and dangerous Northmour is still another staple of the genre, the not quite good not quite bad guy whose motives are played close to the vest.

He is also a figure common to Stevenson’s fiction in the persona of Long John Silver, Alan Breck, or James Drurie.

Northmour and the Frank were at each others throats after staying at the remote pavilion of the title for some time and as the story opens neither has set eyes on the other for years and our hero has been drawn back to their old hangout for no real reason, “a place of dead mariners and sea disaster.â€

He is also, like the heroes of countless adventures to follow about to be plunged into high adventure, international intrigue, high crime, romance, and desperate battle with life and death and the fate of four people at risk beginning when he discovers the pavilion already occupied by none other than Northmour who is there waiting for special cargo off the schooner yacht Red Earl anchored nearby.

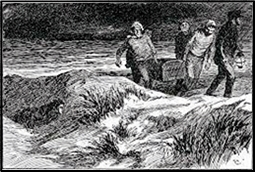

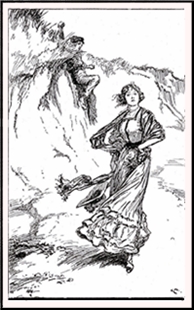

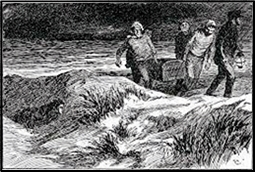

When a mysterious red bearded and exceptionally tall but unhealthy man and a beautiful girl come ashore on a wild and stormy night in the company of Northmour Frank’s curiosity is at fever pitch, not the least because of his instant attraction to the beautiful young woman, who once he has met her mysteriously warns him he is in great danger if the stays camping nearby, and not from Northmour.

The mysterious older man and young woman are father and daughter, Bernard and Clara Huddlestone, the old man a banker who, when he fell into financial trouble, found his only recourse was to ask help of Northmour who had been courting Clara. Northmour, it is suggested in exchange for Clara’s hand, is to smuggle the banker out of England and to safety in the South Pacific, because while trying to avoid his fate Huddlestone became involved with criminal elements, including a group of unforgiving Italians led by a mysterious and possible royal one known as XX whose funds Huddlestone embezzled.

He is not merely fleeing from prison, He is fleeing for his life from a blood vendetta.

Frank and Northmour finally meet again and while Northmour is not happy that Clara has obviously fallen for his friend, he knows he needs help: “… frankly I shall be glad of your help. If I can’t save Huddlestone, I want to at least save the girl…I shall act as your friend until the old man is either clear or dead. But… once that is settled, you become my rival again and I warn you — mind yourself.â€

Cornered and besieged by the Italians in the pavilion, their rivalry over Clara growing, and Northmour’s disgust at the criminal he is trying to save for Clara’s sake tearing at him it all comes to a fine fiery head of self sacrifice and somewhat ill natured nobility, because Northmour is no flowery 19th Century hero, but something of a rogue, a bit of a scoundrel in the Stevenson tradition, and in the tradition of the genre a Janus figure. No Sidney Carton speeches on the guillotine for Northmour.

All of this is the very stuff of an entire genre of British thriller fiction. Like most of Stevenson’s novels this one is still a historical, taking place sometime in the 1830’s or early 1840’s as best I can place it. But it is told in a contemporary voice and could frankly take place in some remote areas today. There are still a few spots on the Scottish coast you could fight a small war largely unnoticed. John Buchan makes some use of something very like this setup in Huntingtower replete with yacht, a princess, and Russians instead of Italians.

The striking thing about the book though is just how familiar it feels to anyone well versed in the genre replete with complex motives, shady figures on both sides, feckless hero caught up in something he doesn’t quite understand, feisty heroine, noble enemies, and of course Northmour the Byronic anti-hero figure who haunts the genre even today.

Storm-driven night, the romance of rough country by moonlight, desperate men in silent pitched battle, stealthy movements in the shadows, sudden death, and unexpected nobility are still a formula for a pretty good adventure story and still driving bestselling fiction today with only a few refinements.