Thu 3 Jul 2014

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: GIRLS ON PROBATION (1938).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[5] Comments

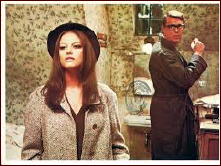

GIRLS ON PROBATION. Warner Brothers, 1938. Jane Bryan, Ronald Reagan, Anthony Averill, Sheila Bromley, Henry O’Neill, Elisabeth Risdon, Sig Rumann, Dorothy Peterson, Susan Hayward. Director: William C. McGann.

Girls on Probation stars Jane Bryan and Ronald Reagan. Although the title suggests that the film will be some form of woman’s prison drama, jail plays only a minor role in this altogether good, albeit uneven, crime film.

Although it’s not a film noir, Girls on Probation is still very much product of the late 1930s and does have several characteristics of what would later be considered film noir. These include a (somewhat) doomed protagonist, a series of events that spin out of control, and a mise-en-scène with a foggy night and a cheap boarding hotel.

The plot follows the steps, or should I say, missteps, of a rather naïve twenty-something woman, Connie Heath (Bryan). Her brutish, although well-meaning, father (Sig Rumann) makes her life miserable. Even worse for Connie is her misbegotten friendship with her friend, the scheming Hilda Engstrom (Sheila Bromley), a co-worker who ends up getting Connie mixed up in two criminal acts.

The first involves the quasi-theft of a dress, which leads to a police record for Connie. The second, and far more serious one, is an armed bank heist pulled off by Hilda’s thuggish boyfriend, Tony. This leads to a stay in the local jail for the two girls. As for Tony, he gets hard time, but later breaks out of prison to join up with Hilda in the girls’ hometown. Since his character is never really developed beyond that of an armed thug, it’s hard to feel bad for the guy when the cops plug him and he plunges off a stairwell.

Throughout the film, Connie’s just a bit too nice for her own good. Fortunately, local attorney Neil Dillon (Reagan) is around to save the day and make everything right again. He also happens to become Connie’s love interest, employer, and fiancé.

Interestingly enough, Bryan, who retired from acting early, and Reagan would remain in touch throughout the years. She and her husband, drug store magnate Justin Dart, would form part of Reagan’s inner circle.

In the pantheon of great crime films from the 1930s and 1940s, Girls on Probation probably really doesn’t really amount to all that much. The film’s ending, in particular, is a bit too sentimental, with Connie needlessly apologizing to the dying Hilda.

Still, Girls on Probation is an above average film with consistently good acting from Bryan. Reagan’s pretty good in this one too, although he’d reprise the role of a prosecuting attorney to much fuller effect in Storm Warning, which I reviewed here. Both films are worth seeing, although the latter is a much more serious film.