Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

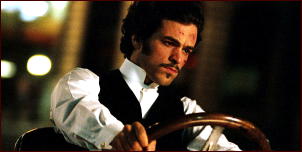

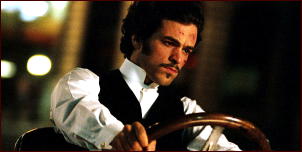

ARSÈNE LUPIN. 2004. Raymond Duris, Kristin Scott Thomas, Pascal Greggory.

Director: Jean-Paul Salomé, Screenplay: Jean-Paul Salomé and Laurent Vachaud, based on the novel La comtesse de Cagliostro (aka The Memoirs of Arsène Lupin) by Maurice Leblanc. In French with subtitles; 131 minutes.

“Louis XI. François 1st. Henri IV. Louis XIV. Arsène Lupin.

“What pride I felt the day I set foot in this forgotten place.

“To have found the lost secret of the Kings of France, to become its master, its only master, to receive such inheritance!”

— Arsène Lupin in

L’Aiguille Creuse (

The Hollow Needle), Chapter 10, by Maurice Leblanc.

For those who only know the name Arsène Lupin, a brief introduction is in order. Lupin is a French gentleman burglar/detective created by journalist Maurice Leblanc (1864-1941) in the feuilletons or newspaper serials that dominated French popular fiction from the days of Alexandre Dumas and Eugene Sue well into the 20th Century.

Lupin debuted in the magazine Le Sais Tout in 1905, and the stories were collected in 1907’s Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar (aka Arsène Lupin in Prison and Arsène Lupin Escapes), following the pattern established by Ponson du Terraill’s picaresque Rocambole two generations earlier.

Twenty volumes followed with The Billions of Arsène Lupin being the last to be published in Leblanc’s lifetime in 1941. Unlike many of his fellow laborers in the disposable newspaper serials, Lupin carved a place for himself as the premier example of the French detective story, his international fans extending to President Theodore Roosevelt and beyond.

A genius with a keen sense of justice, panache, and an ego to match, Lupin is one of the most fully imagined characters in the genre, and the star of countless films, books, comics, and even animated adventures. Three American films, many French films and television series, Japanese films and anime, even a Philippine television series have all followed.

Lupin is a master of disguise and has a small army of identities under which he operates including private detective Jim Barnett, Prince Sernine, Don Luis Perena, M. Lenormand (who rises to no less than the head of the Surete), and others. As often as not Lupin may not be identified as Lupin until late in the tale — if at all.

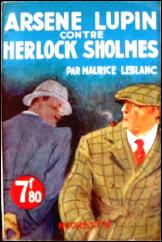

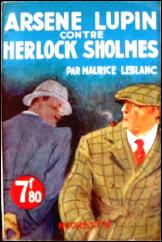

Like most fictional criminals, he changes midway in his career to more detective than thief rivaling Sherlock Holmes with whom he had two memorable encounters (today the books use Holmes’ name, but at the time he was Herlock Sholmès), but even at his most criminal he is a righter of wrongs and defender of the weak, and like Holmes he is given to a sort of manic depression, very high highs and low lows (several times he considers suicide when all is lost).

If Lupin is a younger brother to Raffles, he is at least that or more to the Saint. That said, Lupin is a very Gallic hero, given to dramatic flair and boasting. Compared to Lupin, Poirot, the Belgian, is a shrinking violet.

Over his long career he also acquires a great deal of wealth, numerous wives and lovers, a lost son, and even his own submarine (The Secret of Sarek) given to him for his services to a Moroccan prince (his adventures, both recorded and only referred to carry him to the literal ends of the Earth — to Antarctica, Saigon, Tibet, New York, Morocco … but always back to France).

In 813, the greatest of the Lupin sagas, he only just misses becoming a power in Europe by putting a puppet king on a European throne. He is possibly the most ambitious hero in the genre.

Today the adventures of his non-canonical grandson Lupin III, created by manga artist Monkey Punch and hero of anime and live action films (including The Castle of Cagliostro directed by anime legend Hayao Miyazaki) are better known to most than Lupin himself, but the original still has his charms, and in 2004 he returned to the big screen in a widescreen adventure worthy of a career that began in 1905 and which continues today.

In the 1950’s and 60’s five pastiche of his adventures were penned by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narjeac, authors of Les diaboliques and Vertigo. Today many of the books are still in print, and his adventures continue in pastiche form in the Black Coat Press “Tales of the Shadowmen” anthologies.

Arsène Lupin, the film, is based on Leblanc’s 1924 novel Le comtesse de Cagliostro (in the US and UK, The Memoirs of Arsène Lupin), which recounts the origins of Lupin and his first great adventure.

Taking a cue from that, the film opens with Lupin’s childhood where he is the son of a young woman virtually indentured to her well-married half sister and a teacher of fencing and martial arts (particularly savate — French kick boxing).

The young Lupin is enamored of his cousin, and unaware of the tensions in the house — or that his father is a thief after a fabulous necklace owned by his uncle — in fact the necklace — the infamous piece of jewelry owned by Marie Antoinette that helped to spur the French Revolution and part of the lost jewels of the kings of France.

When the police come for Lupin’s father, he escapes, but returns and enlists Arsène to steal the necklace, but he is apparently killed in a struggle with an accomplice within sight of the famous “Needle” a peculiar shaped rock off the French coast, and Arsène and his mother are exiled from their home, young Arsène swearing revenge on society and particularly on his uncle and men like him.

Some years later we meet the youthful adult Arsène (Raymond Duris) on board a gala yacht for a costume ball. Despite his grand manner, monocle, and white tie and tails he is little more than a pickpocket, but a talented one.

It’s at this point he meets the beautiful Countess Cagliostro, Josephine Balsamo (Scott Thomas), who claims to be the granddaughter of Joseph Balsamo. the notorious Count Cagliostro, charlatan, con man, and according to some, alchemist and wizard. (See Dan Stumpf’s review of the film Black Magic and his review of the Alexandre Dumas pere novel Joseph Balsamo elsewhere on this blog.) She takes young Arsène under her wing as her lover and student and transforms him from a mere pickpocket into a master criminal.

But there are dark undercurrents stirring. There is a mysterious cabal of wealthy men sworn to protect the secrets of the lost jewels of the French kings, plus the dangerous man who serves them and is the sworn enemy of Josephine, — the strange scarred man who serves Josephine and distrusts Arsène, and Josephine herself — who rumor has it is not the grand daughter of Cagliostro, but the daughter — the immortal daughter over a century old.

Eventually Lupin breaks with her, but by now he too is sworn to uncover the secrets of the lost treasure of the king’s of France which leads him back to the cousin he once loved as a youth.

Thus begins the duel of wits between Lupin and the Countess and the cabal who protect the lost treasure. Cross and double-cross, buckled swashes, gallant gestures, disguise, and the elegance of France in another age are on display in a handsome film that manages to keep tongue in cheek in true Lupin style while never laughing at itself or the audience for enjoying it.

Though the plot is complex and elements from several of the Lupin novels are brought in, the plot is easy to follow, and Duris makes a charming Lupin, one who grows from something of a talented ruffian in gentleman’s clothing to a master criminal and suave adventurer.

He has a gamin quality, a rougher edge beneath the suave exterior that gives the character more depth than simply another charming adventurer — much like the original by Leblanc. Thomas as Josephine is simply lovely and clearly having fun playing the wicked and treacherous Josephine, and Eva Green as Lupin’s true love is both touching and beautiful in what could have been a throwaway role.

I’ll go no farther in describing the plot because I can’t without giving away too much, but needless to say, there are surprises to be had, and twists unexpected, before the film reaches its end, leaving you satisfied and wanting more.

But that said, and for any treasure hunters out there, despite the film and Leblanc’s book, the famous Needle which features in the film and the Lupin novel, The Hollow Needle, is not hollow, but solid rock. The lost treasures of the French kings will have to be found somewhere else.

Arsène Lupin is a beautifully shot film that seems to have that same slightly golden glow of photographs of that gilded age. It’s not only a handsome film to look at, but one of the most lavish and playful any genre film has earned. It is also faithful to both the letter and spirit of the Leblanc novels. It’s more than worthy of Lupin and his adventures.

And a word has to be said for the cinematography of Pasal Ridao. The film is a delight to look at with stunning camera work and sets and costumes adding real depth to the proceedings.

Lupin was played by John Barrymore in Arsène Lupin (1932, with Lionel cast as his nemesis Inspector Ganimard and Karen Morley in a racy pre-code role as an undercover police agent helping to trap Lupin — it’s delightfully ripe old time cinema) and Melvyn Douglas in Arsène Lupin Returns.

Charles Korvin played the role in a later film. In France, Robert Lamoureaux, George Descrieres, Jean-Claude Brialy, and Jean-Pierre Cassel have all played Lupin in several films and television series (available in boxed sets, but in French).

There have also been Lupin comics in France, an animated series, and there were several radio series, one hosted by Lupin himself. In Japan Lupin was played by a Japanese actor in live action films and later featured in an anime aside from the popular Lupin III films and series. In the Philippines a series about a wealthy playboy who was really a thief was called Lupin ran and is also available on DVD.

Lupin has also appeared in Jean-Marc and Randy Lofficier’s “Tales of the Shadowmen” anthology series from Black Coat Press, most recently in my own “The Jade Buddha” in volume 5 of that series in which he encounters the real model for Fu Manchu, Hanoi Shan.

There are several good French sites for Lupin, and you can learn a good deal more about him at the sites for Black Coat Press and the French Wold-Newton Universe including full bibliographies, chronologies, and filmographies.

Many of the Lupin books are in print, and those that are not relatively easy to find for the most part, and quite a few are available to read online or download as free ebooks including Leblanc’s two science fiction novels and a few of the non-Lupin novels.

But even if you don’t want to dip into his literary adventures, treat yourself to this lavish and enjoyable film. Few creations in the genre have received so faithful or so lush a tribute.