WHAT IS A CRIME CLASSIC?

by Josef Hoffmann

If we were to believe the language of publishers, booksellers and collectors, there is a multitude of so-called “crime classics.†And yet not every crime novel that has exercised a certain appeal on a particular number of readers, even decades after its publication, deserves the attribute “crime classic.â€

At a time of “retromania†(Simon Reynolds), at a time in which computers, the internet and e-books can and perhaps will tend to compile, store and make accessible all texts, longevity in itself is not sufficient as a criterion.

The term “crime classic†denotes a distinction, a seal of quality, which raises the novel concerned above the average, especially when books are produced and distributed more or less industrially in masses. So which crime novels have the prerogative to maintain a presence and to claim the attention of generations of readers?

If we try to determine the particular characteristics of a crime classic, we might concentrate on the intrinsic qualities of the narrative text, such as an ingenious plot and lustrous prose, or on extrinsic features such as its continuous presence in the book market over decades and special regard among literary critics.

At any rate, “classic†in the sense of a crime novel does not mean that it corresponds to the literary-aesthetic ideals of a so-called classic era, that it distinguishes itself from romantic or realistic or other epochal styles, or that it demonstrates a particularly exquisite language.

Classic is also not identical to nostalgic. That said, any nostalgic reading need, satisfied by a certain crime novel that revives good old or bad old times, does not necessarily mean that the novel is not a crime classic.

It seems obvious to assume a complex interplay of the intrinsic and extrinsic qualities of a crime novel, which ultimately lead a particular crime novel to stand the test of time, to still appear “fresh†even after decades have passed, and to enrich its reader.

I now intend to examine more closely how such interplay works, creating tradition and literary history.

While Edmund Wilson’s infamous polemic “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?†might be arrogant, it does provide an opportunity to undertake certain differentiations. A distinction must first be made between “crime classics†and the classics of world literature.

“Crime classics†are not classics that also happen to be crime novels. “Crime classics†require other criteria of attribution. If we were to apply Wilson’s standards of modern classic literature (James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann), there would be at most a dozen crime novels that would meet these standards and deserve the title of “classic.â€

Using Gertrude Stein’s criteria for “masterpieces†would produce even fewer. In her view, masterpieces do not describe the things of reality, recognised by the reader to his enjoyment; rather, they create and embody a being in themselves, something fundamentally new. This is the case in very few crime novels, if at all in any.

Furthermore it should be noted that a “crime classic†is not automatically every work by any crime author who has also written, among other things, a few “crime classics.†If, for example, we consider the best, most successful crime novels by Agatha Christie to be “crime classicsâ€, this does not mean that her weaker publications should also achieve this status.

Crime authors are rarely so perfect, from a literary point of view, to suggest that those who have written a number of “crime classics†will never dip below this level, and always write masterfully. Such an assumption is disproved by many weak crime novels by good authors.

Ultimately, the criteria for all subgenres of crime novels are not the same. Different standards apply to the traditional whodunit, which make the novel a “crime classic,†than to a gangster story or a psycho thriller.

In a whodunit much more emphasis is placed on a perfectly structured, thoroughly logical and at the same time original plot, on the clever distribution of “clues†throughout the text and a surprising and plausible solution to the riddle than is the case in a gangster story.

What is required of all “crime classics,†however, is that they demonstrate a certain superior level of prose, and that their specific dramatic suspense works.

One criterion that is insufficient to qualify a novel as a “crime classic†is some random innovation; e.g., a particular method of murder or a criminal deduction technique, which is presented in a novel for the very first time. In spite of the innovative element a crime novel might still be written using lousy language and a sloppy plot, so that the predicate “crime classic†is not appropriate.

Equally insufficient is the fact that a crime writer (or his works) was read widely at the time and showered with praise by critics. I question, therefore, whether even a single work by Edgar Wallace deserves to be considered a “crime classic†although he was appreciated by highly competent authors such as Gertrude Stein, Dashiell Hammett and H. R. F. Keating.

Positive acknowledgement by literary critics is an extrinsic feature. A prerequisite here is continuity over a long period of time, which does not mean that all criticism highlights the same aspects of a crime classic and appraises them positively. Perspective and standards can shift, particularly over the course of decades.

Not every critic must provide identical reasons for his praise. A further extrinsic characteristic of a crime classic is that it is generally read more than once. Especially in the case of the traditional whodunit a large time span is often left between readings, so that the forgetful reader can try to solve the mystery anew.

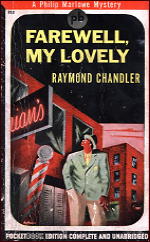

But we should remember Chandler’s criterion that a really good crime novel must also provide reading pleasure even if the last chapter is missing (and even if the experienced reader figures out the end of the story).

In other words, every crime classic must possess literary qualities and may not profit merely from the uncertainty as to how the story ends. It must touch the reader, so that scenes, lines of dialogue, comparisons or other elements of the novel become indelible in his memory. It may not leave one cold, but instead must challenge the reader to adopt a position for or against the crime novel or some of the statements contained therein.

More specifically, a crime classic must distinguish itself by means of such a complex power of literary qualities that a single reading, or a reading in a particular historical period, does not exhaust these literary riches, but rather the work provides new aspects for later readings or subsequent generations of readers.

Upon first perusal in youth, the aspects that play a role and are assessed positively will be different to those in more mature years, or in later life. The manner in which this is caused by a crime novel might well remain a mystery to most readers, upon which critics and literary scholars can continue to work. I only wish to warn against awarding the distinction of crime classic prematurely to all old crime novels that appear, in some way, to be worth reading.

To conclude, here are some suggestions related to the discussion: Are the following crime novels crime classics or simply cult novels for those in the know?

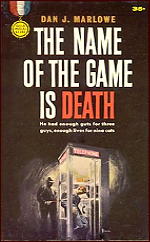

Dan J. Marlowe: The Name of the Game Is Death (1962), praised by Ed Gorman, Stephen King.

Ted Lewis: Jack’s Return Home (1970), praised by Paul Duncan, Max Décharné.

Simon Troy: Waiting for Oliver (1963), praised by Mary Ann Grochowski, Bill Pronzini.

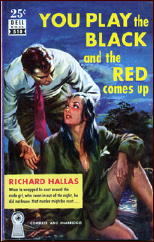

Richard Hallas: You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up (1938), praised by David Feinberg, E. R. Hagemann.

Vin Packer: Whisper His Sin (1954), praised by Anthony Boucher, Jon L. Breen.

Mildred Davis: The Room Upstairs (1948), praised by Marvin Lachman, Jean-Patrick Manchette.

Norbert Davis: The Mouse in the Mountain (1943), praised by Bill Pronzini, Ludwig Wittgenstein.

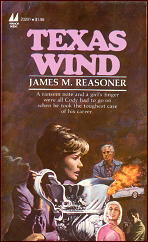

James Reasoner: Texas Wind (1980), praised by Ed Gorman, Bill Pronzini.

Sources:

Italo Calvino: Warum Klassiker lesen?, Munich/Vienna 2003 (English edition: Why Read the Classics, in: The Uses of Literature, 1986)

Raymond Chandler: Raymond Chandler Speaking, edited by Dorothy Gardiner & Kathrine Sorley Walker, London 1962

J. M. Coetzee: Was ist ein Klassiker?, Frankfurt am Main 2006 (English edition: What Is a Classic?: A Lecture, in: Stranger Shores. Literary Essays 1986-1999, New York 2001)

T. S. Eliot: Was ist ein Klassiker?, in: Ausgewählte Essays, Berlin/Frankfurt am Main 1950, 469-511 (English edition: What Is a Classic?, London 1945)

H. R. F. Keating: Crime and Mystery: the 100 Best Books, London 1987

Ezra Pound: ABC des Lesens, Frankfurt am Main 1967 (English edition: ABC of Reading, New York 1934)

Gertrude Stein: Was sind Meisterwerke. Essay, Zürich 1985 (English edition: What Are Masterpieces and Why Are There So Few of Them?, 1940)

Edmund Wilson: Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?, in: Howard Haycraft (ed.): The Art of the Mystery Story, New York 1992, 390-397

Translated by Carolyn Kelly.