Thu 19 Jul 2012

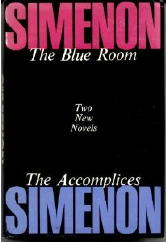

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review: GEORGES SIMENON – The Blue Room and The Accomplices.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[2] Comments

by George Kelley & Marcia Muller

GEORGES SIMENON – The Blue Room and The Accomplices. New York: Harcourt Brace & World, hardcover, 1964. Published separately in UK by Hamish Hamilton, hardcovers, 1965/1966. Translations of Le Chambre Bleue (Paris, 1964) and Les Complices (Paris, 1955).

While Simenon is best known for his Maigret novels, his non-series works of psychological suspense are equally compelling. They express a kind of dark inevitability, a sense of events unwittingly set in motion by one’s actions and then gathering an uncontrollable momentum of their own. This volume presents two of the best of these novels.

In The Blue Room, Simenon explores the erotic — and ultimately disastrous — relationship of an innocent man and a woman who is as ruthless as she is passionate. Tony’s main interest in life is making love with his mistress, Andree.

Naive and trusting, he remains unaware of her evil nature until his wife and her husband are found dead of strychnine poisoning. Tony is arrested for the crimes, and the story of what went before is told in flashback as he is questioned by the police.

Even though we already know where the events are leading, we nevertheless fear for Tony as we watch Andree’s corruption overwhelm him; and their final encounter of the lovers at the trial is one of the more chilling in mystery fiction.

The Accomplices is completely different in tone and theme from The Blue Room, but equally haunting.

Joseph Lambert is married, the father of six children, and has another on the way. A fairly successful businessman, Lambert feels everything is going his way.

But then the unexpected happens: While Lambert is driving wildly down the road, engaged in an amorous dalliance with his secretary, he loses control of his car. A school bus filled with children swerves to avoid him, but crashes into a wall and bursts into flame; dozens of little children die in the accident.

Lambert moves quickly to cover up his guilt, but his unconscious proves to be his own prosecutor, judge, and jury. This is a fascinating novel of psychological torment and pressure, and has grave implications for modern society.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.