Thu 23 Jul 2009

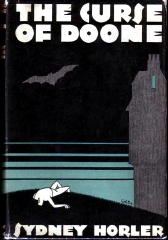

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS review: SYDNEY HORLER – The Curse of Doone.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[9] Comments

by Bill Pronzini:

SYDNEY HORLER – The Curse of Doone. Hodder & Stoughton, UK. hardcover, 1928. Mystery League, US, hardcover, 1930. US paperback reprint: Paperback Library 53-931, 1966.

A journalist and writer of football stories (the British variety) until his early thirties, Sydney Horler began publishing “shockers” in 1925 and went on to produce upwards of a hundred over the next thirty years.

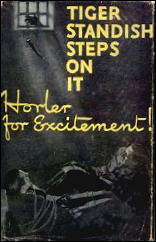

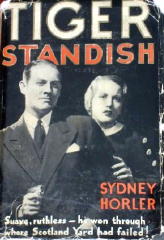

He created a menage of series characters, most of them Secret Service agents of one kind or another, including Bunny Chipstead; “The Ace”; Nighthawk; Sir Brian Fordinghame; and that animal among men, Tiger Standish.

The Standish books — Tiger Standish Steps on It (1940) is a representative title in more ways than one — were especially popular with Horler’ s readership. His greatest literary attribute was his imagination, which may be described as weedily fertile.

His favorite antagonists were fanatic Germans and Fu Manchu-type megalomaniacs, many of whom were given sobriquets such as “the Disguiser,” “the Colossus,” “the Mutilator,” “the Master of Venom,” and “the Voice of Ice”; but he also contrived a number of other evildoers to match wits with his heroes — an impressive list of them that includes mad scientists, American gangsters, vampires, giant apes, ape-men from Borneo, venal dwarfs, slavering “Things,” a man born with the head of a wolf (no kidding; see Horror’s Head, 1934), and — perhaps his crowning achievement — a bloodsucking, man-eating bush (“The Red-Haired Death,” a novelette in The Destroyer, and The Red-Haired Death, 1938).

The Curse of Doone is typical Horler, which is to say it is inspired nonsense. In London, Secret Service Agent Ian Heath meets a virgin in distress named Cicely Garrett and promptly falls in love with her. A friend of Heath’s, Jerry (who worries about “the primrose path to perdition”), urges him to toddle off to his cottage in Dartmoor for a much needed rest.

Which Heath does, though not before barely surviving a mysterious poison-gas attack. And lo! — once there, he runs into Cicely, who is living at secluded and sinister Doone Hall.

He also runs into a couple of incredible coincidences (another Horler stock-in-trade); monstrous vampire bats and the “Vampire of Doone Hall”; two bloody murders; hidden caves, secret panels and caches; a Prussian villain who became a homicidal maniac because he couldn’t cope with his sudden baldness; and a newly invented “war machine” that can force enemy aircraft out of the air by means of wireless waves and stop a car from five miles away.

All of this is told in Hoder’s bombastic, idiosyncratic, and sometimes priggish style. (Horler had very definite opinions on just about everything, and was not above expressing them in his fiction, as well as in a number of nonfiction works. He once said of women: “Of how many women can it truly be said that they are worthy of their underclothes?” And of detective fiction: “I know I haven’t the brains to write a proper detective novel, but there is no class of literature for which I feel a deeper personal loathing.” Racism was another of his shortcomings; he didn’t like anybody except the English.)

This and Horler’s other novels are high camp by today’s standards; The Curse of Doone is just one of several that can be considered, for their hilarious prose, pomposity, and absurd plots, as classics of their type.

Unfortunately, most of Horler’s “shockers” were not reprinted in this country. Of those that were, the ones that rank with The Curse of Doone are The Order of the Octopus (1926), Peril (1930), Tiger Standish (1932), Lord of Terror (1937), and Dark Danger (1945).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.