REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

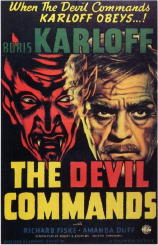

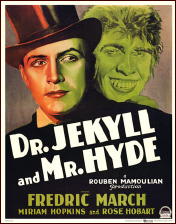

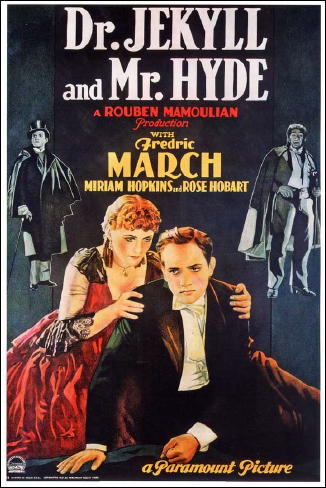

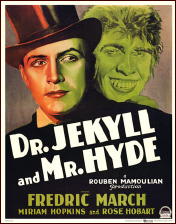

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE. Paramount Pictures, 1931. Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Holmes Herbert, Halliwell Hobbes, Edgar Norton, Tempe Pigott. Screenplay: Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath, based on the story by Robert Louis Stevenson. Director: Rouben Mamoulian.

In 1931, two films were released that are still being shown in theaters and on television: James Whale’s Frankenstein and Tod Browning’s Dracula. Their great popularity initiated the horror cycle of the thirties.

A third film was released that year whose subject was, like Frankenstein, the creation by a brilliant, eccentric scientist of a creature who threatens his creator’s life and sanity, but Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is director Rouben Mamoulian’s only horror film, and it has languished in relative obscurity,

The film’s fluid, imaginative camera work, for which Mamoulian was noted, allies it to the best horror/fantasy films of the period as well as to the innovative musicals that were Mamoulian’s chief subjects in his long Hollywood career. It may be of some interest to note, in this respect, Whale’s direction of the 1936 Showboat, and to suggest that in their free use of non-realistic elements, the musical and horror films of the thirties are not unrelated.

Mamoulian’s adaptation, like the other film versions of Robert L. Stevenson’s novella, places great emphasis on the laboratory and transformation scenes and, unlike the source, doesn’t attempt to conceal the nature of Hyde’s identity from the audience.

(In Stevenson’ s story, Hyde is the evasive criminal whose secret Mr. Utterworth, the lawyer-investigator wryly calling himself Mr. Seek, sets out to uncover, making of the adventure at once a morality and a detection tale.)

The laboratory is the conventional workshop of the thirties’ horror film, a classical locus that is at its most poetic and imaginative in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein. It is also a dramatic stage which gives some slight plausibility to the drug-induced emergence of the Hyde personality.

Mamoulian’ s principal interest is probably not in the horrific or suspenseful elements of the story, although his film is lacking in neither of these. His Hyde — a curious Simian-Negroid creation that may strike some viewers as a rather blatant ethnic stereotype — is certainly repulsive enough, but I think the director’s real subject is the consequences of the release of all inhibitions, his Hyde brooking no interference with any of his immediate needs and desires.

This is most evident in the careful portrayal of the apparent distinction between Jekyll, the staid Victorian lover (even if unconventional scientist), and Hyde, the sensual, brutal lover whose pleasure is in a sadistic inflicting of pain on his mistress. And it is in the tactful but powerful depiction of Hyde’s relationship with his mistress (marvelously played by Miriam Hopkins) that the originality of this film in its relation to the horror film lies.

The male/female relationships in the Hollywood horror films of the period tended to be chaste, unlike the franker treatment in other genre films: the rampant visual/sexual puns in the Busby Berkeley musicals, the poetic physicality of the Tarzan/Jane relationship in the first two MGM Weismuller/O’Sullivan films and Kong’s famous — and later edited — undressing of Fay Wray in King Kong.

If one of the cherished memories — and cliches — of the monster chasing and sometimes carrying the heroine to a possible but never realized fate worse than death, the sexual play in these films is relatively tame.

Not so in Mamoulian’s Jekyll. One of the best sequences — still memorable and unsettling is of Hyde’s unexpected return to his mistress’s chambers and his subsequent vicious teasing before he strangles her in a grim and deadly parody of the sexual embrace.

It has often been said that the Horror of Dracula (Hammer Films, 1957) made explicit the eroticism of the vampire myth; what should also be pointed out — and perhaps for its irony — is that in the year that Browning’ s Dracula presented the classic version of the gentleman vampire, Mamoulian’s night-creature (like Dracula, freest and most powerful in his mistress’ s bedroom) tortured and teased and sexually abused his lover a way that the “mainstream” horror film would only dare to follow a quarter of a century later.

The classic horror film has its narrative source in Victorian taboos and the way in which they are circumvented by the monster created in the laboratory or the grave. The vampire is the dark lover, the sensual bringer of pleasure and death, so unlike the correct, cardboard hero.

In Mamoulian’s film, the hero and the villain inhabit the same body. His Jekyll (Fredric March) has been criticized for his wooden playing, but what has not to my knowledge been pointed out is the way in which, as Hyde increases in strength, Jekyll comes to resemble him.

There is a striking scene when Jekyll returns home, free he thinks of Hyde but dressed in the cape and top-hat affected by his other self and in his extravagant gestures more like the exuberant Hyde than the controlled scientist.

But, then, Hyde was never far from Jekyll as the scientist pursued his obsession with the separation of the dual self, an obsession whose consequences are finally as destructive as Hyde’s natural genius for evil.

Early in the film, before Jekyll effects his first transformation, the good doctor treats a patient in her room. This patient is Ivy, the prostitute Hyde will pursue and kill, and as Jekyll takes his leave of her after they are surprised by his friend Lanyon in a passionate embrace, Ivy whispers seductively, “Come back,” and languorously, voluptuously moves her bare leg enticingly back and forth.

Mamoulian superimposes the shot of her leg and the echo of her invitation over the following scene as the supposedly blameless Jekyll and his friend walk away from the apartment. Sex and science are both seductive siren calls, and the breaching of limits is fatal for both scientist and lover.

Call Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde a morality play, a scientific romance, a monster film with many of the genre’s conventions, a psychological flirtation with the mysteries of the self, this superbly crafted and haunting film is an artful extension of the possibilities of the horror film, and it has a power to disturb that still sets it apart from most other genre films of its time.

� This review first appeared in

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 7, No. 1, January/February 1983.