THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

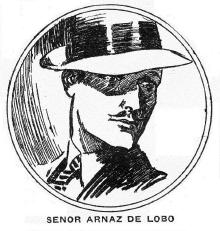

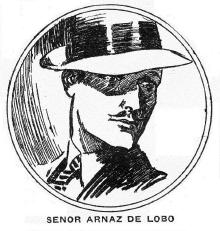

#15. Senor Arnaz de Lobo, Soldier of Fortune, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

Senor Arnaz de Lobo … announces himself bored with life… But Senor Lobo makes no secret of his dissatisfaction. The world, he claims, has become too civilized to offer adventure. (The Choice of Weapons)

Erle Stanley Gardner (1889-1970) is probably best known for his long-running series about the always victorious lawyer, Perry Mason, but he also had hundreds of exciting stories in the pulps. Many of these appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly, where he had multiple series running: Senor Arnaz de Lobo, Sidney Zoom, Lester Leith, the Patent Leather Kid, The Man in the Silver Mask, and other standalone stories that could have been turned into series. The Lester Leith series seems to have been the most popular in the magazine, but the other series were popular as well.

The Senor Lobo stories are fun, action-packed stories that were nothing like the other detective and mystery stories in the magazine. Senor Lobo and his friend, El Mono Viejo, are basically soldiers of fortune thrown into the midst of a city where they continually find adventure and danger.

Lobo is like a knight errant, always ready to jump to the defense of a lady in danger or to right a wrong. Of course, the adventurers don’t turn down any money that comes their way, and many a criminal finds himself divested of his cash after running into them. Here is a paragraph from the beginning of one their adventures that describes Lobo:

To appreciate the character of Senor Arnaz de Lobo, revolutionist, soldier of fortune, and gang buster, it must be remembered that he was hard. Governments are not overthrown, even in South and Central America, save by courage, valor, and a certain ability to capitalize circumstances. (A Matter of Impulse)

His physical description is given early in the series:

Standing in the doorway was six feet of lean, whip-corded strength, bronzed by tropic suns. Dark eyes surveyed them in scornful appraisal. He was attired in a natty spring suit. In his right hand he carried a light cane. The left hand held the hat… (Gangsters’ Gold)

He reveals that he is only part Spanish — his mother was Spanish and his father American, and he himself is an American citizen. This brings the question as to whether his name had been changed or was originally Lobo. He can speak not only English and Spanish but also French and Chinese. He fought in Central and South America and also in China and Africa.

Events from the past are often alluded to in the course of their American adventures. El Mono Viejo’s real name is not given in the series, just his nickname and description: “which means ‘The Boss Ape,’ short, abnormally broad of shoulder and long of arm, his eyes round and brown.†(Costs of Collection)

Although Senor Lobo often uses guns in the course of his adventures, his favorite weapon is his sword cane. It has a retractable blade, and Lobo often uses it in confrontations with criminals. Lobo kept weapons of various kinds in his car that would be of use in close quarter fighting, including hand grenades.

One story describes an outing against gangsters thusly: “And now as they swept into this gangster hide-out, each man carried two hand grenades, two guns, extra clips of shells, and a tear gas bomb.†(The Sirens of War)

So they were well prepared for any fighting to be done, which is more than most of the criminals up against them could claim. Senor Lobo also had a special car for his adventures – a roadster “specially constructed for power, acceleration, and an ability to take right angle turns at high speed.†(Broken Eggs)

Unfortunately, Lobo’s adventures were rough on equipment, and the car was shot to pieces by a machine gun in “Broken Eggs.†However, doubtless he had it repaired or acquired another because cars were indispensable in his work.

Another requirement for his work was a safe place to live. He had to constantly change his apartments whenever their location was revealed, often abandoning his belongings at the same time. “To maintain safety it was necessary that he keep himself well under cover. The place where he had his apartment was known to but two people, El Mono Viejo and himself.†(Carved in Jade)

Lobo also tried to keep his whereabouts secret from the police. As El Mono Viejo stated about the police viewpoint: “They are angry now at our methods. They say we are as much of a menace to law enforcement as are the gangsters upon whom we war.†(Carved in Jade)

In virtually every story the soldierly professionalism of Lobo and his lieutenant are stressed, and the lack of such qualities in their gangster opponents is also stressed. In fact, the gangsters’ lack of ability to handle the tactics of the two soldiers of fortune is shown to best effect in the story “Barking Dogs.†Here the two soldiers raid a gangster headquarters in order to rescue a woman, and defeat a gangster mob many times their size. Afterwards, the gangsters claimed to the police and newspapers that twenty rival gangsters had raided their stronghold, and asked for a police investigation. Clearly, they never knew what hit them.

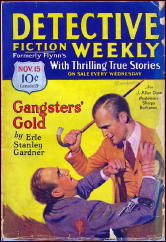

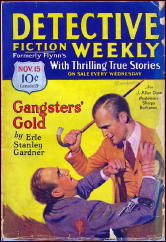

The series, which ran for 23 stories, starts out with basically a two-part beginning, though each can be read separately and were published four months apart. In “The Choice of Weapons†and “Gangsters’ Goldâ€, the two parts of the opening story, Lobo is up against a hard fight with Butch Pender and his gang. These early stories are full of action, with Lobo out-maneuvering the gangsters twice in their attempt to rob gold from a bank. Lobo originally came to the U. S. in response to a strange situation. It seems that a dying American gangster named High Test Barker, wanting revenge on his enemies, makes a will leaving $70,000 in gold to Senor Lobo.

The will makes the condition that Lobo can have the money only if he avenges Barker’s death. So Lobo comes up to take care of the situation and steps into what might be termed a hornet’s nest of trouble. The first stories are based upon this plot. After it runs its course, Lobo becomes involved in one adventure after another in the city.

The series seems to have quite a lot of the influence of Leslie Charteris’ series about The Saint (who appeared in DFW itself in 1938-39 and 1943). However, there was nothing like it in the magazine during the series run from 1930-34.

Detective Fiction Weekly boasted many series, and none of them were remotely similar to Senor Lobo. Plenty of professional detectives, both private and government, ran through the pages. Also plenty of amateur detectives of all kinds appeared in stories. Senor Lobo fell into none of these categories. He was a professional who enjoyed what he did as a mercenary and revolutionary, as well as his new work as a gangbuster.

Lobo was at his happiest when engaged in a conflict. He states to a woman: “sometimes I feel the lust for adventure in my blood… Perhaps I’ll pull out one of these days and start another revolution.†(Gangsters’ Gold)

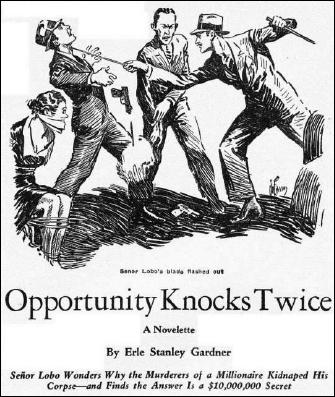

He does eventually leave for another revolution — in the last story, “Opportunity Knocks Twiceâ€, he and his assistant leave the city for Latin America for this purpose.

In an example of Lobo’s predilection for getting into trouble, see the story “The Sirens of Warâ€. In this story, Lobo is bored with inaction and soft living. He is pacing the late night sidewalks of the city looking for action. As his assistant, El Mono Viejo, says, “it has been a week, and we have had no action.â€

So they wander the streets until, finally they find some trouble to get involved in. Trouble in the form of a kidnapping of a wealthy woman. Lobo involves himself in the matter to the extent that he goes after the kidnappers and in a couple of violent shootouts wipes them out. He returns the ransom money, minus what he takes for expenses.

The expenses are what Lobo refers to in other stories as “the costs of collectionâ€, and usually run ten per cent of the money returned. (Costs of Collection)

Lobo gets involved in more conflicts with criminals by investigating any strange occurrence that strikes his interest. After things quieted down too much, he got the idea of paying taxicab drivers to report unusual occurrences to him. This helped keep Lobo busier, even if only part of the drivers’ reports led to action against criminals.

Another example of Lobo’s penchant for getting into trouble occurs in “Carved in Jadeâ€, an early story. This one starts in Chinatown, a popular setting for Gardner. Lobo wants to eat Chinese food, but his visit to a Chinese restaurant involves him with a group of gangsters who try to kill him in a trap. Lobo is up against both American and Chinese criminals in this story.

One of the funnier stories is “Costs of Collectionâ€, where Lobo and his friend are almost broke, thanks to their bank going under with all of their money in it. Far from finding it to be a bad situation, the two adventurers laugh about the situation and decide they have to make more money.

“Caramba!†said El Mono Viejo, “but we need guardians, we two. We put money in a bank, and presto! We cannot take it out!†So Senor Lobo needs to find some gangsters to fight and money to appropriate. He uses almost the last of his money to pay for information from a cabdriver, and as a result finds some crooks to fight and a young woman to rescue. Coincidentally, Senor Lobo takes $10,000 in cash from some crooks as what he calls the “spoils of warfareâ€. So he is back in the money again.

By the time of the story “A Hundred to Oneâ€, many of the local gangsters were fed up with Lobo’s interference in their affairs and made attempts to eliminate him by setting traps. In the words of one newspaper that Lobo saw, they intended “to rid the city of a “disturbing influence†in the shape of an independent adventurer, who seemed to enjoy interfering with gang activities for the sheer pleasure of the ensuing conflict.â€(A Hundred to One)

Lobo smiled at the article; all he wanted was some excitement and conflicts with the gangsters were one way to do this. In fact, he tells El Mono Viejo: “We can ask but three things of life, beautiful women, hard fighting—and a clean getaway.†(A Clean Getaway)

So we can assume this is the philosophy of Senor Lobo. But he has another philosophical comment in another story: “Senor Arnaz de Lobo snapped out his philosophy of life in a single sentence: “I am not afraid to die,†he said, “nor do I want to be afraid to live.†(The Spoils of War)

El Mono Viejo is constantly warning Senor Lobo to beware of beautiful women, because their enemies may use them as bait for traps for him. Nevertheless, Lobo continues to enter the traps. As he says: “Trap or no trap, I like the bait. There is beauty and adventure, a woman and danger, a mystery and a threat. I know of no better combination.†(A Clean Getaway)

El Mono Viejo is much more serious-minded than Lobo, and more cautious. Lobo occasionally calls him “Sobersides†to poke fun at his serious attitude. El Mono Viejo enjoys the action and adventure, but he sees matters differently: “life is a stern reality.†(Leaden Honeymoon)

The Senor Lobo series was undoubtedly more fantasy than reality based, but it was the kind of crime-fighting stories that appealed to readers, as shown by the fact that it lasted for 23 stories and probably could have run longer.

Each story features Senor Lobo and El Mono Viejo becoming involved in gangster activities, and usually culminates in a violent gun battle (sometimes with explosives used).

Naturally, Senor Lobo always comes out on top and wins the girl when one is part of the conflict. El Mono Viejo told Senor Lobo “it was a wonderful idea of yours — this business of coming to the city and antagonizing organized crime.†(Opportunity Knocks Twice). He only complained when there was insufficient action.

The last story, “Opportunity Knocks Twice,†is a fast-moving tale of action, started when a taxicab driver’s report of a very unusual occurrence puts Lobo on the trail of a $10 million secret and murder.

At the same time, Lobo and El Mono Viejo are getting ready to offer their services to a revolutionary, who is in the city buying arms for a revolution in Latin America. If he doesn’t want their services, then they will offer them to the opposing side.

By this time, El Mono Viejo is tired of the “guerilla warfare†with the city’s gangsters, and wants nothing more than to leave so they can get involved in a war or revolution. So the story is of the two mercenaries running around trying to resolve the murder and at the same time keep an eye out for when the time is ripe to leave for Latin America.

The title refers to the two opportunities that Senor Lobo has in the story: firstly the murder and secondly the revolution. As Senor Lobo says at the end of the story: “In our profession,†he said, “one does not overlook opportunity’s second knock.â€

So the series has a conclusion of a sort, as the two prepare to leave the city they have lived in for over four years. It is certain that the criminals will not miss them.

This is an excellent series that deserves reprinting. As this series was finishing its run in 1934, another series was beginning that seems to show some influence of Senor Lobo: the Park Avenue Hunt Club series of Judson P. Philips. This was a small group of men who were devoted to fighting gangsters, and enjoyed their work. Though it is doubted if they ever enjoyed it to the extent that Senor Lobo did.

The Senor Arnaz de Lobo series by Erle Stanley Gardner:

The Choice of Weapons July 12, 1930

Gangsters’ Gold November 15, 1930

Red Hands December 6, 1930

A Matter of Impulse February 7, 1931

Killed and Cured February 21, 1931

Carved in Jade May 9, 1931

Coffins for Killers July 25, 1931

No Rough Stuff December 5, 1931

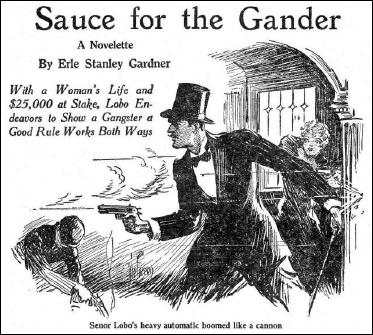

Sauce for the Gander December 12, 1931

Barking Dogs March 26, 1932

A Hundred to One April 30, 1932

A Private Affair June 25, 1932

Trumps November 12, 1932

A Clean Getaway December 3, 1932

Tickets for Two December 31, 1932

The Spoils of War January 14, 1933

Leaden Honeymoon March 11, 1933

Results May 6, 1933

The Sirens of War September 16, 1933

Costs of Collection November 18, 1933

The Code of a Fighter January 27, 1934

Broken Eggs May 5, 1934

Opportunity Knocks Twice October 27, 1934

Note: An earlier version of this article appeared in Blood ‘n’ Thunder magazine (#16, Fall 2006).

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by Harold de Polo.

12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.

13. HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE, by J. Lane Linklater.

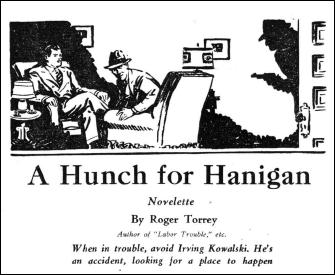

14. HANIGAN & IRVING, by Roger Torrey.