Tue 1 Dec 2015

Mike Nevins on HARRY STEPHEN KEELER (Post-THANKSGIVING Edition).

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns[6] Comments

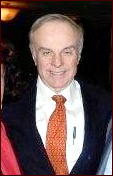

by Francis M. Nevins

I’ve never had much interest in Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) but somewhere along the line I wound up with a copy of Jan Cohn’s biography IMPROBABLE FICTION (1980). A few weeks ago, for no particular reason, I started idly skimming through this book. At least it was idle skimming until a paragraph on page 155 brought me up short. It seems there was a time early in the 20th century when Rinehart became interested in spiritualism.

As we learn from Cohn: “Mary and Stan [her husband] probably had their first experience with spiritualism in 1909, at Lily Dale near Chautauqua, where there was a spiritualist camp. Both had sittings there with a medium named Keeler. First they wrote notes on a slate and awaited replies that were to come through Keeler. Stan wrote notes to his father, his brother Charlie, and a young doctor friend, but the replies were unsatisfactory. A trumpet seance followed and Stan’s brother Charlie spoke, but again it was unconvincing.â€

The Keeler mentioned here didn’t make it into the index of Cohn’s book, obviously because she didn’t know the rest of his name. I do. I had read about this spiritualist before, and I remembered where. Not to keep anyone in suspense, he was the uncle of Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967), the nuttiest filbert who ever sat down to a typewriter and one of my favorite writers ever.

Harry’s first wife had died of cancer in 1960, and her death so devastated him that for the next three years he was unable to write fiction. He did, however, bang out a long series of “Walter Keyhole†newsletters. These in effect constituted a low-tech blog, printed on multi-colored paper, discussing any subject that caught his fancy—cosmology, autobiography, writers’ gossip, religion, restaurants, cats, whatever — and mailed out on an irregular basis to almost everyone for whom he had an address.

The hobby, or whatever you want to call it, cost him up to $50 a week, an amount not to be sneezed at in those days, but he obviously felt the price was worth it and kept it up, although less frequently, even after he remarried and until about six months before his death. Over the decades I acquired originals or photocopies of 188 of these newsletters, and several years ago I organized the material in them into THE KEELER KEYHOLE COLLECTION (2005), a hefty volume which I still thumb through with enjoyment every so often. I knew that was where I had first heard about Harry’s slate-writing uncle, and finding the relevant passages plus a bit of time with my good buddy Joe Google brought me up to speed.

Pierre L.O.A. Keeler (the initials stand for Louis Ormond Augustus) was born in 1855, or perhaps 1856, and died in 1948 at age 92, or perhaps 93. Late in 1960 Harry wrote in one of his Keyhole newsletters that Pierre,

A few months later, after reading a piece about Pierre in the National Enquirer, he complained in another Keyhole that the Enquirer “neglected completely to point out that the high spot of his work was to bring out messages from the ‘dead’ not only upon the slates brought by his clients, but in actual handwritings of the dead.â€

Are we to conclude that Harry believed Unc was a genuine medium? Not at all. In a later Keyhole, probably dating from the summer of 1963, he claims to have known Pierre “fairly intimately†and describes him as “a consummate sleight-of-hand artist, deriving his astounding results via various methods, [and] was, therefore, a charlatan. Was, in short, exactly like all male members of the tribe of Keeler.†No Mike Avallone-style I’m-the-greatest hype for Harry!

Googling Pierre’s name, we find that he was quite a character, continuing his slate-writing career for decades despite being exposed again and again by a number of psychic investigators including Houdini. Could he have fooled people on the same scale in the Internet age that allows us to learn so much about him with so little effort? Probably. There’s an old Latin proverb, mundus vult decipi, the world wants to be deceived, that I suspect remains true today.

Writing about his uncle, Harry consistently misarranged his middle initials, L.A.O. instead of L.O.A. I don’t know if we should make anything of this, but it’s a sober fact that the female lead in one of the most charming Keeler novels, Y. CHEUNG, BUSINESS DETECTIVE (1939), is a young woman of Chinese-Hawaiian descent named Loa Marling. Did Harry derive that name from his uncle Pierre’s middle initials?

Writing about Harry can easily become habit-forming, for me anyway. I acquired the habit back in my teens when I first discovered HSK, and here I am about to turn 73 and still hooked!

Having become a lawyer and law professor during those intervening decades, I have a particular interest in Harry’s take on that subject. Very few of his books have lawyer protagonists but one of those few is the first Keeler novel that I ever stumbled upon. The main character in THE AMAZING WEB (1930) is David Crosby, a young attorney who screws up his first big case—where the defendant is the woman he loves!—but goes on several years later to prove himself a tiger of the courtroom, with a golden future as a criminal defender ahead of him and, as Keeler Koinkydink would have it, the same young woman at his side. Here, at the end of more than 500 pages of plot labyrinth, is where David Just Says No.

Instead David decides to buy a farm and devote the rest of his life to producing “clean sweet food for the thousands.â€

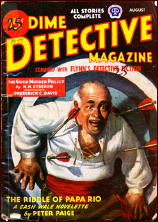

The other Keeler novel with a lawyer protagonist offers a more positive view of the profession and is also of historical importance because its protagonist is a woman. THE CASE OF THE LAVENDER GRIPSACK (1944) is the fourth and final volume of what today is known as the Skull in the Box series. Elsa Colby, recent graduate of Chicago’s Northwestern Law School, has signed a Keeler Krackpot Kontract that will divest her of title to a valuable piece of real estate known as Colby’s Nugget, and vest title in her rascally uncle Silas Moffit, if she should be disbarred or lose a criminal case within a certain number of months.

For obvious reasons Elsa is accepting no cases and spends her time making a quilt. Moffit pressures Judge Hilford “Ultra Legal†Penworth to compel her to defend a capital case she can’t possibly win and to disbar her on the spot — which is within the judge’s power as Chief Commissioner of the Ethical Practices Subdivision! — if she refuses. To understand what the case is about you have to read the three previous Skull in the Box books — THE MAN WITH THE MAGIC EARDRUMS (1939), THE MAN WITH THE CRIMSON BOX (1940) and THE MAN WITH THE WOODEN SPECTACLES (1940) — but any readers not up to that ordeal may substitute the summary I wrote for the second edition of Jon L. Breen’s NOVEL VERDICTS (1999).

The trial — for a murder that took place less than 24 hours earlier! — is to be held in the drawing room of Judge Penworth, who is suffering from a bad case of gout. The courtroom action is full of long-winded speeches and light on Q-and-A but packed with Keeler’s inspired daffiness — and with sentences like this one and several of those above which feature long asides punctuated with an exclamation point! The crossword puzzle exegesis in Chapter 13 is guaranteed to pop the eyeballs of every cruciverbalist, and the surprise ending will knock the socks off any reader with the patience to hang on till the end. As in THE AMAZING WEB, although this time the attorney is the woman and the client the man, they’re clearly going to get married after the book is closed.

Thanksgiving is two days away as I finish this column. In the years of his widowerhood Keeler endured a number of long and lonely turkey days, and an entry in a Walter Keyhole newsletter written late in 1962 memorializes one of them.

I hope everyone who reads this column had a far more pleasant holiday than that.