The Amazing Colossal Belgian:

A Quartet of Christie Expansions

Part 3: “Dead Man’s Mirror”

by Matthew R. Bradley

Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot story “The Second Gong” (Ladies Home Journal, June 1932; The Strand Magazine, July 1932) was collected in The Witness for the Prosecution and Other Stories (1948). It was expanded considerably as “Dead Man’s Mirror,” which debuted in Murder in the Mews and Other Stories (1937) with three other novellas; Mews was published in the U.S. as Dead Man’s Mirror, initially minus “The Incredible Theft,” restored in 1987. Serialized in the London Daily Express (April 6-12, 1937), “Theft” was expanded from “The Submarine Plans” (The Sketch, November 7, 1923; The Blue Book Magazine, July 1925), originally collected in The Under Dog and Other Stories (1951).

“Gong” is set on a single night at Lytcham Close, the ancestral home of musician Hubert Lytcham Roche, the last of his line, whose megalomaniacal behavior is either eccentric or certifiable, depending upon who is asked. Among his obsessions is punctuality at dinner, announced with a gong at precisely 8:05 and 8:15 P.M., and woe betide any guest who is tardy.

It opens as Hubert’s nephew, Harry Dalehouse; Joan Ashby, invited at his behest by the “vague” Mrs. Lytcham Roche; and Geoffrey Keene, Hubert’s secretary, converge in the hall, having heard what Joan insists is the second gong, but although it is now 8:12, butler Digby says it is the first, dinner being delayed for 10 minutes by the late 7:00 train.

Astounded at this unprecedented departure from tradition, they hear a sound, but cannot agree what it was—a shot, perhaps from a nearby poacher? a car backfiring?—or which direction it came from. They are soon joined by Hubert’s wife; adopted daughter, Diana Cleves, a distant cousin; and friend and financial advisor, Gregory Barling, yet when the second gong sounds, Hubert is not in evidence.

As the drawing-room door opens at last, it is not he but Poirot who enters, then Digby reports that Hubert came down at 7:55 and entered the study, whose locked door Poirot has Keene and Barling force, revealing him dead of a shot that passed through his head and apparently shivered a mirror on the wall.

The gun below his hand, locked French window, and paper bearing just a scrawled word, “Sorry,” suggest suicide, the conclusion reached by Inspector Reeves, who amiably says he needs no co-operation from the unconvinced Poirot. Yet his manie de grandeur is not consistent with suicide, and Poirot explains he was summoned by Hubert, who thought he was being swindled, declining to call in the police for “family reasons.”

Barling says that Hubert was receptive to the idea of Diana marrying him and admits he is in love with her, yet she has “played fast and loose with every man for twenty miles around,” and has been “seeing a lot” of the new estate agent, Captain John Marshall, who lost an arm in the war.

Di, who says she was in the garden when the shot was heard, calls Barling a crook, while Keene—seen with the “eyes in the back of [Poirot’s] head” picking up something outside the study—states it was a tiny silk rosebud from her handbag, and Marshall confirms that Hubert lost a bundle speculating on Barling’s “[w]ildcat schemes.”

Poirot finds two pairs of footprints in the garden where Di had picked Michaelmas daisies for the table and later a rose to cover up a grease spot on her dress. Convening everyone in the study, he shows how jarring a loose mechanism can lock the French window from outside, then elicits the terms of Hubert’s will: Di inherits…provided a potential husband takes the family name.

Yet a recent codicil stipulates that if said husband is not Barling, then Harry inherits, and Poirot “put[s] the case against” Di—who flirted with Keene to deflect attention from true intended Marshall—before he fingers Keene. Shot with a silencer, the fatal bullet hit the gong, heard only by Joan in her room above, and was later retrieved by Keene, who then dropped it under the mirror he’d cracked to help stage the scene, smoothing out Di’s first footprints in the flower bed to conceal his own; he later fired his revolver out the window before dashing from the drawing room into the hall, giving him his alibi for 8:12. Harry generously offers to halve the estate with Diana, disinherited for refusing to wed Barling.

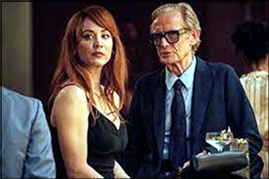

“Dead Man’s Mirror” features a return appearance by Mr. Satterthwaite, who was usually seen in Christie’s stories of Harley Quin but crossed paths with Poirot in Murder in Three Acts (1934), first serialized in The Saturday Evening Post (June 9-July 14, 1934) and then published in the U.K. as Three Act Tragedy. Adapted by ITV with David Suchet in 1993 for Series 5 of Agatha Christie’s Poirot, “Mirror” backtracks to Poirot receiving the letter in which Gervase Chevenix-Gore imperiously summons him to Hamborough Close. At a duchess’s party, he seeks out Satterthwaite—given neither explanation nor introduction—to pump him regarding the old family (“Sir Guy de Chevenix went on the first crusade”).

The novella also briefly describes his journey, but beginning with his arrival, many of the mechanics of the story, even specific passages, are anologous, with the usual renaming of characters (if not always in a one-to-one correspondence). Di, Marshall, Digby, Barling, Harry, and Joan are roughly equivalent to, respectively, Ruth, Captain John Lake, Snell, Colonel Ned Bury, Hugo Trent, and his girlfriend, Susan Cardwell. Keene is effectively bifurcated into secretary Godfrey Burrows and research assistant Miss Lingard, assisting Gervase with the family history; newly added lawyer Oswald Forbes notes that “my firm, Forbes, Ogilvie and Spence, have acted for the…family for well over a hundred years.”

Local law is here represented by Major Riddle, the Chief Constable of Westshire County, whose investigation—with old friend Poirot—puts to shame the cursory one by Reeves, a virtual walk-on. Christie eliminates much of the humor inherent in the collective surprise over the host’s failure to appear for dinner, but compensates with his wife, Vanda, a self-professed reincarnation of Egyptian queen Hatshepsut and “a Priestess in Atlantis,” who claims to see Gervase’s spirit in the study. Forbes explains that although he disapproved of his sister’s marriage, his proposed new will stipulated that Ruth marry Hugo, not Bury, whose ill-advised investment was in the Paragon Synthetic Rubber Substitute Company.

It is Lingard whom Poirot espies picking something up, which she identifies as a pencil that Bury had made out of a bullet fired at him in the South African War, and murdered Gervase with Ruth—secretly wed to Lake three weeks earlier—as a motive. Bury reveals that unknown to her, she was no distant cousin, but the illegitimate daughter of Gervase’s brother and a typist, who’d “renounced all rights” after he died in the Great War. Poirot’s apparent accusation of Ruth has the desired effect and Lingard confesses, confirming the truth privately to Poirot: she was the typist, who wanted to protect Ruth’s happiness by preventing the new will, and burst a blown-up paper bag to simulate the sound of a shot.

— Copyright © 2024 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Up next: Remembered Death

Editions cited —

“The Second Gong” in Witness for the Prosecution: Dell (1979)

“Dead Man’s Mirror” in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories: William Morrow (2013)