Sat 6 Aug 2022

A PI Mystery Review by Tony Baer: LEIGH BRACKETT – No Good from a Corpse.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

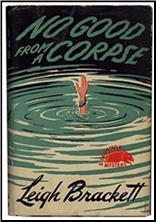

LEIGH BRACKETT – No Good from a Corpse. Coward McCann, hardcover, 1944. Title story of No Good from a Corpse (Dennis McMillan, hardcover, 1998, along with eight short stories. Handi-Books #32, paperback, date? Collier, paperback, 1964.

Los Angeles private detective Ed Clive is in love with Laurel: a nightclub singer, cute, sprightly, and equally in love with him. But Laurel can’t be true. They both know it, so Clive keeps things platonic. It’s the only way to keep Laurel interested — kinda like an unneutered Jake and Lady Brett Ashley in Sun Also Rises. But he loves her desperately, nonetheless.

Laurel’s a lady with a past. A past that includes Clive’s ex-best friend Mick. Mick and Clive grew up together. Mick screwed around with Clive’s girlfriend back when they were 18, and Clive has neither forgiven nor forgotten.

But when Laurel is found bludgeoned to death with Mick’s walking stick, Clive is the only one who thinks it’s a set-up. Clive’s the only guy between Mick and the gas chamber.

Clive starts out the story with pretty good wits and one-liners. Asked why he’s not wearing his laurels, he says he’s afraid they’d sprout in the rain. When he tells a rival to leave Laurel be, the rival says “I’ve always wondered what God looked like.†“Now you know,†Clive retorts.

But once he loses his love, darkness cuts a swath across his world. Places “smelled of many people, many things, none of them clean.†A woman’s “face slid away from under popped brown eyes as though it was too tired to stay put.†“[T]he blacked out neons … gave an eerie feeling of desolation, as though Clive was the last man walking on a dead world.†At the screaming pleading pleas of “‘Oh God. Oh God’ …. Clive doubted whether God was worried much.â€

While Clive solves what turns out to be a crime of Byzantine complications, and saves Mick from death, he ends the book with the downbeat thought that “of all things, never to have been born is best.â€

It’s an excellent Chandleresque detective novel — apparently excellent enough to convince Howard Hawks that Leigh Brackett ought to partner equally with William Faulkner in drafting the Big Sleep screenplay.

I’m a big fan of standalones. They give the author the freedom to put their characters thru the ringer; to destroy them or resolve their conflicts; to leave nothing left. A standalone leaves the reader always wondering, unsure of the ground on which they stand. There’s not the relative safety of a recurring series character (a la James Bond) who you know will come out of the thing relatively unscathed. Private detective standalones are fairly rare.

This is a good one.