CORNELL CLUB:

The Woolrich Adaptations of François Truffaut

by Matthew R. Bradley

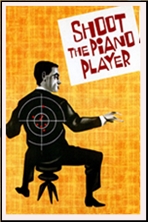

It is no surprise that the term film noir is French, given how avidly Gallic filmmakers and/or critics (some were both) embraced what we now know as noir fiction and its cinematic counterpart, or that they turned to the former as source material. The novels of David Goodis, for example, were adapted into not only the Bogart/Bacall vehicle Dark Passage (1947) but also the likes of François Truffaut’s Tirez sur la Pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player, 1960), based on Down There (1956); Henri Verneuil’s Le Casse (aka The Burglars, 1971), based on The Burglar (1953), filmed Stateside in 1957; and La Lune dans le Caniveau (The Moon in the Gutter, 1983), directed by Diva (1981) phenom Jean-Jacques Beineix.

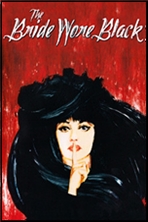

While Henry Farrell may be best known as the original author of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1960), and thus the “Godfather of Grande Dame Guignol,†Truffaut’s 1972 adaptation of his 1967 novel Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me (aka Une Belle Fille comme Moi [A Gorgeous Girl Like Me]) is surely noir, and Truffaut also filmed two books by the arguably definitive noir writer, Cornell Woolrich: The Bride Wore Black (1940), part of his celebrated series of “Black†Novels, and Waltz into Darkness (1947), published under his pen name of William Irish.

Made in England, Truffaut’s controversial 1966 version of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) had been a considerable departure, his first film in English and in color and his only SF effort, shot by future director Nicolas Roeg rather than usual cinematographer Raoul Coutard. But he was back on his literal and metaphorical home turf with La Mariée Etait en Noir (The Bride Wore Black, 1967), shooting in France and adapting another noir novel with familiar faces both behind the camera (Coutard and co-scenarist Jean-Louis Richard) and in front (Jeanne Moreau, Jean-Claude Brialy).

The legendary book-length interview Hitchcock/Truffaut (1966) had recently been published, and the fact that the Master of Suspense’s Rear Window (1954) was also based on Woolrich story is one aspect that makes this perhaps Truffaut’s most Hitchcockian work, as is carrying over composer and Hitch mainstay Bernard Herrmann from Fahrenheit in their second and final collaboration.

The film is basically a quintet of set pieces in each of which the title character, Julie Kohler (Moreau), kills a man, making sure he knows her identity, e.g., she pushes Bliss (Claude Rich) from his balcony during a party when he tries to retrieve her windblown scarf; lures Coral (Michel Bouquet) to a rendezvous where she poisons him; and leaves Rene Morane (Michel Lonsdale) to suffocate in a sealed closet while his son, Cookie (Christophe Bruno), slumbers upstairs.

Flashbacks gradually reveal that she is avenging the death of her childhood sweetheart, David (Serge Rousseau), shot dead on the church steps after their wedding as the five fooled around with a loaded rifle across the street. The film addresses neither how Julie tracks down the men — strangers drawn together on a single occasion, sharing only a predilection for guns and women (the latter ultimately their undoing), who fled, never to meet again — nor whether David’s accidental killing justifies theirs.

Julie clearly has her own idea of justice, leading her to call the police and clear Cookie’s teacher, Miss Becker (the striking Alexandra Stewart), as whom she posed, by providing details only the killer could know.

I don’t know how, or even if, the novel tackles any of these questions, yet in a sense, it doesn’t matter; we don’t turn to Cornell Woolrich for rigorous logic but for his fever-dream imagination and style, and Truffaut himself, obviously interested more in the effect than in explanations, begins to play with our expectations as Julie’s next target, Delvaux (Daniel Boulanger), is suddenly arrested for unrelated crimes, so she turns to the last on her list, artist Fergus (Charles Denner).

When she begins posing for him as the bow-wielding huntress (how apt!) Diana, we suspect how he will meet his end, yet for the first time, she seems hesitant after Fergus, anticipating Denner’s role as Truffaut’s L’Homme Qui Aimait les Femmes (The Man Who Loved Women, 1977), avows his amour.

It is around this point that Truffaut uses maximum cinematic sleight of hand, misdirecting us with a subplot about how Fergus’s friend Corey (Brialy) remembers seeing Julie at Bliss’s party and tries to identify her.

Having watched in step-by-step detail as she dispatched each of her previous victims, we are genuinely surprised when Truffaut abruptly cuts back to Fergus lying dead with an arrow protruding from his body, and even more so when the seemingly relentless avenger leaves an incriminating mural of herself on the wall, which along with her attending the artist’s funeral leads to her arrest and confession, albeit without explanation.

But — as my first-time-viewer wife quickly deduced — it is all a means to an end, and as Julie, with knife concealed, delivers meals to inmates of the same prison where Delvaux is confined, we await the inevitable off-screen shriek as she finishes her mission.

Asked by Le Monde in 1968 if Hitchcock had influenced the film, the director said, as quoted in Truffaut by Truffaut (*), “Certainly for the construction of the story because, unlike the novel, we give the solution of the enigma well before the end [as in Hitch’s Vertigo (1958)]…. Contrariwise, the desire to make the characters speak of everything else but the intrigue itself is decidedly not very Hitchcockian and more characteristic of a European turn of mind.â€

In 1978, he called it “the only one I regret having made… I wanted to offer…Moreau something like none of her other films, but it was badly thought out. That was a film to which color did an enormous lot of harm. [A permanent rift with Coutard reportedly left Moreau sometimes directing the actors.] The theme is lacking in interest: to make excuses for an idealistic vengeance, that really shocks me…. One should not avenge oneself, vengeance is not noble. One betrays something in oneself when one glorifies that,†as he opined to L’Express.

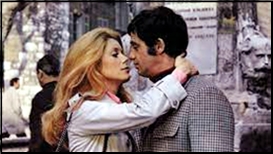

Truffaut’s Woolrich adaptations were made with only one film (my personal favorite of his), Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses, 1968), in between; the fatalistic nature of the second, Mississippi Mermaid (1969) — whose title seems more appropriate in French, La Sirène du Mississippi, given the sinister connotations of “siren†— makes it not too surprising that, per New York Magazine critic David Edelstein’s TCM introduction, it was his biggest financial failure, but I think it deserved better.

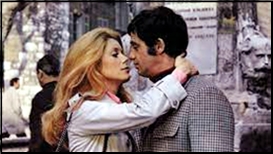

The first of his features on which Truffaut had sole screenwriting credit, it updates Woolrich’s 1880 New Orleans setting to the contemporary French island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean, to which the ship Mississippi brings a woman (Catherine Deneuve) claiming to be Julie Roussel, the mail-order bride of Louis Mahé (Jean-Paul Belmondo, whom I have loathed since seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s seminal French New Wave debut, À Bout de Souffle [Breathless, 1960]). She doesn’t match the photo that Julie had sent him, but Louis clearly falls for her at first sight and marries her anyway.

She says she sent a photo of a neighbor to ensure that Louis did not marry her for her looks, while he wrote that he was the foreman and not the owner of a cigarette factory, because he did not want to be married for his money. After “Julie†cleans out his bank accounts and disappears, Berthe Roussel (Nelly Borgeaud) arrives, and we learn that her sister was murdered aboard the ship by Richard (Roland Thénot), who later abandoned accomplice Marion Vergano, so they hire private detective Comolli (Bride alumnus Bouquet) to find the impostor.

In France, Louis spots Marion in some news footage — precisely paralleling D’Entre les Morts (From Among the Dead, 1954) by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the source novel for Vertigo — then locates and confronts her, but is unable to kill her; Louis shoots Comolli when he gets too close and refuses to take a bribe, and the couple’s peripatetic future as fugitives seems bleak, despite Louis forgiving Marion for trying to poison him and her declaration of love.

When I saw this for the second time (c. 2014), the first being in the 1999 “Tout Truffaut†retrospective at the hallowed ground of New York’s Film Forum, it seemed surprisingly familiar. It’s true that at various times I have also read Waltz into Darkness (I was honored to be asked to weigh in on whether Viking Penguin, where I was then employed, should reissue it, which they did) and seen the 2001 remake, Michael Cristofer’s Original Sin, notorious for its steamy scenes between Antonio Banderas and Angelina Jolie — talk about something for everyone — but I think there’s more to it than that, perhaps something distinctively Woolrichian.

His future biographer, Francis M. Nevins, Jr., wrote in Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers that “love dies while the lovers go on living, and [he] excels at showing the corrosion of a relationship between two people,†plus the theme of imposture recurs in I Married a Dead Man (1948), also filmed in France as J’ai Éspousé une Ombre (I Married a Shadow, 1983), starring Nathalie Baye.

“I read [the novel] when I was doing the adaptation of The Bride Wore Black,†Truffaut told Le Monde in 1969. “At that time, I actually read everything [he] wrote in order to steep myself in his work and to keep as close as possible to the novel, despite the unfaithfulness necessary in films. I like to know thoroughly any writer whose book I transpose to the screen [as he had with Goodis and Bradbury]…. My final screenplay was less an adaptation in the traditional sense than a choice of scenes. With this film, I was finally able to realize every director’s dream: to shoot in chronological order a chronological story that represents an itinerary…. [The] shooting began on Réunion Island, continued in Nice, Antibes, Aix-en-Provence, Lyons, to finish in the snow near Grenoble. The fact of respecting the chronology permitted me to ‘build’ the couple with precision….The Mermaid is above all else the tale of a degradation through love, of a passion.â€

(*) Text and documents compiled by Dominique Rabourdin; translated from the French by Robert Erich Wolf (New York: Abrams, 1987).

___

Portions of this article originally appeared on Bradley on Film.