December 2009

Monthly Archive

Wed 2 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

Reviewed by MIKE DENNIS:

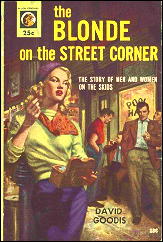

DAVID GOODIS – The Blonde on the Street Corner. Lion #186, paperback original; 1st printing, 1954. UK edition: Serpent’s Tail, softcover, 1998.

“Ralph stood on the corner, leaning against the brick wall of Silver’s candy store, telling himself to go home and get some sleep.”

That’s the opening line of The Blonde On The Street Corner, a 1954 novel written by David Goodis. Of course, Ralph doesn’t go home. Instead, he spots a blonde across the dark street and gawks at her. She eventually calls him over to light her cigarette, which he does.

Now, at this point, one might expect that Ralph would be lured into a tight web spun by this dazzling femme fatale, resulting in his eventual moral destruction, if not death. But Goodis doesn’t write that way. In fact, the blonde is fat, sharp-tongued, and lives in the neighborhood. Ralph knows her, and knows that she’s married. She propositions him right on the corner, but he rejects her. “I don’t mess around with married women,” he tells her. Then he goes home.

Much to the reader’s surprise, this encounter does not trigger the plot of the novel. In fact, it would be right to say that the novel has no plot, in the usual sense. Ralph returns to his impoverished Philadelphia home and spends the rest of the book wallowing in misery with his friends, all of whom are in the same boat as he: in their thirties, usually unemployed, and filled with unrealistic dreams.

One of his friends says he is a “songwriter,” but no one has ever recorded any of his songs. Another wants to be a big-league baseball player, but lasted only a week on a class D minor league team.

They spend most of their time leaning up against buildings, wearing only thin coats against the bitter Philadelphia winter, and wishing they had more money. They talk a good deal about going to Florida, where they can get jobs as bellmen in a “big-time hotel,” convinced this would jump-start their desperate lives.

The book goes on like this pretty much all the way through, with no moving story line, but it’s Goodis’s prose that keeps you riveted to the page. No one can paint a picture of a hopeless world better than he can.

For Goodis, Philadelphia is a desolate place, whose bleak streets offer little in the way of promise. Many of his novels were set there, and they all shared that common trait. Life in that city is, for him and his characters, usually an exercise in futility.

These are people who walk around with twenty or thirty cents in their pockets, who cold-call girls out of the phone book asking for dates, and for whom escape to Florida is always right around the corner. The finale provides the mortal body blow to Ralph, stripping him of the last shred of his dignity.

The Blonde On The Street Corner is a potent novel, filled with the passions and despair of its characters. All through this book, you find yourself longing to run into characters whose lives mean something. Then, you realize there aren’t any.

Copyright � 2009 by Mike Dennis.

Wed 2 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

TV mysteries1 Comment

Hi Steve,

1. The Wolfe Pack is screening one of the infamous widescreen Missing Minutes episodes of the A&E Nero Wolfe television series this Friday, Dec. 4th, in NYC: “Prisoner’s Base.” There’s a downloadable brochure online on the Wolfe Pack’s Home Page, which describes the event, and also in the Missing Minutes section of the website:

www.nerowolfe.org

http://www.nerowolfe.org/htm/AE/missing_minutes/missing_minutes.htm

2. The Jim Hutton-David Wayne Ellery Queen series is reportedly getting a legitimate release next year:

http://tvshowsondvd.com/n/13043

Cheers,

Tina Silber

Tue 1 Dec 2009

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

GEORGES SIMENON – Maigret and the Enigmatic Lett.

First published as The Strange Case of Peter the Lett: Hurst, UK. hardcover, 1933. First US edition: Covici Friede, hardcover, 1933. Translation of “Pietr-le-Letton” (Fayard: Paris, 1931). Also published as: Maigret and the Enigmatic Lett, Penguin, pb, 1963.

Superintendent Maigret, of No. 1 Flying Squad, looked up from his desk; he had the impression that the iron stove which stood in the middle of his office, with its thick black pipe sloping up to the ceiling, was not roaring as loudly as it should. He pushed aside the paper he had been reading, rose ponderously to his feet, adjusted the damper and threw in shovelfuls of coal.

Then standing with his back to the stove, he filled a pipe, and tugged at his shirt collar; it was a low one, but felt too tight.

And so we meet Jules Maigret in his too small office in the Quai des Orfevres, a large and deliberate man who always seems a little outside of his environment, a little uncomfortable in it.

The first of Maigret’s cases finds the good Commissar at the top of his game. Pietr the Lett is an international criminal that Interpol identifies as headed for Paris. Maigret heads for the train station at the Gare du Nord to intercept Pietr only to find a man fitting his description dead in the train toilet.

Inside the dead man’s pocket Maigret finds a photograph and a lock of red hair. Maigret and his man Torrence lunch at the Brasserie Dauphine behind the Place de Justice for the first time and discuss the case. It will become a familiar scene. Is Pietr dead, or two men — or more? Soon a virtual army of Pietr’s aliases present themselves.

With the help of the police lab at Quai de Orfevres, Maigret is lead to a couple, the Mortimer-Levinson’s, staying at the Hotel Majestic, millionaires and friends of one Oswald Oppington, and he follows the trail of one Olaf Swann, a Norwegian merchant marine officer to Mme Bertha Swann living in Fecamp.

Maigret has his man Torrence posted at the hotel and he travels to Fecamp where he follows a Russian, Fedor Yurovich, a Russian drunk, back from Mme Swann’s to the Jewish Quarter of Paris where he is living with a dancer, Anna Gorskin, physical age 25, but with a much older and more tarnished soul:

Her hair was greasy and unkempt, hanging down to her shoulders in thick strands. She wore a shabby dressing gown, which hung open, showing her underwear. Her stockings were rolled down past her podgy knees.

For the first time we see Maigret in his familiar form, cold, wet, and tired, even his famous pipe wet watching the goings and comings of the criminal classes. He is watching and waiting. He is biding his time, and soon he will act. But only when the time is right.

Later Maigret is wounded while following the Mortimer-Levinson’s from a night club. He rushes to the Hotel Majestic to find Torrence murdered, both attacks the work of the dancer Anna Gorskin.

Now Maigret tightens his web in the pursuit of the Lett, who has re-emerged, and finally tracks down the killer, revealing the mystery of the enigmatic criminal known as Pietr the Lett. Maigret, taking a note from the classical detective novel, allows the defendant an easy out.

The second bottle had a little rum left in it. The Superintendent picked it up. It clinked against the glass as he poured.

He drank slowly. Or rather he pretended to drink. He was holding his breath.

At last the report came. He drained the glass at one gulp.

And then he goes home to Mme Maigret. Until the next case.

From the beginning Maigret is something different. The writing is controlled and succinct. There is little extra verbiage, and Maigret himself is not given to colorful action or dress. He is a drab policeman enshrouded in a fog of pipe smoke, sipping Calvados, a beer, or a glass of Pernod at some small brassierie, steady, patient, and as inevitable as the dawn as he moves forward toward the truth through the lies, self delusion, and human frailties of the men and women he must investigate and pursue.

It would perhaps be an exaggeration to suggest in the course of an enquiry, cordial relations often develop between the police and the individual from whom they are trying to obtain a confession.

But unless the criminal is a soulless brute, a kind of intimacy almost always grows up.

This is the famous method of Maigret, the gradual cajoling, bullying, empathizing with the suspect as he uncovers the truth one layer at a time.

This is Maigret as Hemingway first encountered him, writing as Sim or sometimes Simenon, a Belgian journalist whose stories flowed from his pen in seeming endless progression growing darker, deeper, and more psychologically complex as time passes.

The Maigret novels invite us into a world that is at once familiar and foreign. Like Holmes’s London or Chandler’s L.A., Maigret’s Paris is a living place, a character itself, and realized so deftly that though in the background it is ever present in our unconscious mind.

But few debuts in crime fiction are as assured and complete as this one, and the remarkable thing is that it is the same voice and the same character we will know so much more about some eighty books later. Maigret, unlike many great fictional characters, comes to life fully formed sprung from the forehead of Simenon complete and instantly recognizable.

Few great detectives emerge so fully imagined on their first outing. For most there are stumbles, missteps, false starts. But Maigret, pipe puffing away, is here, as always, one with his world and ours, patiently nursing a glass of Calvados, his pipe smoke curling about him, his overcoat a bit too heavy for the weather, his great mind waiting to leap upon the truth, his great soul ready to embrace the frailties of the human beings he must deal with on a daily basis. This, too, is the method of Maigret.

Note: While I don’t think this book was adapted as one of the Maigret films. it was adapted as as an episode of at least three of the many international television series based on the character, including the best known British series with Rupert Davies (see above).

Tue 1 Dec 2009

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

BABETTE HUGHES – Murder in Church. D. Appleton-Century, hardcover, 1934.

Sir Arthur Quinn is a famous astrophysicist who is the bane of the religionists. He had shown “the theologians to be charlatans, religions to be apologies, and his more cautious confreres to be opportunists.”

Besides that, he is given to amorous intrigues, mushrooms for breakfast, and the sucking of fruit lozenges. It is the latter habit, possibly combined with the second, that brings about his death as he rather uncharacteristically attends Sunday services at St. Barnabas Church. Someone had coated several lozenges with muscarin, a poison that is derived from mushrooms.

Among the possibilities for the distinction of bumping him off are President Radford of the Western Institute of Technology, a pompous oaf who tries vainly to reconcile religion and science; Yozan Saijo, a Japanese physicist whom Quinn has insulted; Quinn’s “sexless” wife who worships him despite his philandering; a professional dancer whose movements were harsh and whose interpretations were grotesque and often venomous, and who had been one of many of Quinn’s inamoratas; George Coburn, Quinn’s valet, an ex-English jockey who sports a black eye given him by Quinn; a fanatically religious Russian technician, and others too numerous to mention.

Quinn had religious, scientific, and personal enemies, it seems.

Ian Craig, professor of Oriental literature at Stanford and frequent quoter of the aphorisms of Ti Li, is the amateur investigator. He gained some little renown when he solved the case chronicled in Murder in the Zoo (1932), another academic mystery.

This is one of the selections in “The Tired Business Man’s Library,” chosen to “afford relaxation and entertainment for everyone interested in Adventure and Detective Fiction.” Murder in Church meets that goal, but only barely.

– From

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 5, Sept-Oct 1987.

Bio-Bibilographic Data. [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

HUGHES, BABETTE (Plechner). 1906-?? Born and resident in Seattle; graduate of University of Washington; wife of playwright Glenn (Arthur) Hughes; author of numerous one-act plays.

Murder Murder Murder. French, pb, 1931. One-act play.

Murder in the Zoo. Appleton, 1932. [Prof. Ian Craig]

Murder in Church. Appleton, 1934. [Prof. Ian Craig]

Tue 1 Dec 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

THOMAS PYNCHON – Against the Day. The Penguin Press, hardcover; First Edition, 21 November 2006. Trade paperback: Penguin, October 2007.

I spent most of August re-reading The Brothers Karamazov, which I won’t review here because Dostoyevsky don’t need me to pimp for him.

I just mention it by way of saying that after I finished its 800-plus densely-packed pages, I swore to read a few lighter, shorter things for the next couple months — then got sucked into picking up Thomas Pynchon’s 2006 mega-novel Against the Day.

I loved it, laughed out loud as I read it (a thing I seldom did with Karamazov) got involved with the characters and absorbed in the stories. But the damthing’s nearly 1100 pages long!

This is a book of biblical proportions, with myriad plots, sub-plots, sub-subplots, long discursions into physics, metaphysics, boys’-adventure-dime-novels and kinky sex, with references to everything cultural, pop-cultural and subcultural. And then even more references, from obscure pagan deities to 50s rock&roll.

There’s even a website to explain all the references. (See also the Wikipedia page.) Minor characters long-forgotten resurface hundreds of pages later and take over the narrative for chapters on end, and stories veer from hard-rock realism to ethereal unreality.

But ultimately, if it’s about anything at all, Against the Day is probably about the line between surrealism and fantasy and how it defines our dreams. As such, I recommend it to anyone with time on their hands and an unabridged dictionary by their side.

Others be Warned: this is a book that could defeat the reader.

Tue 1 Dec 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE LETTER. Paramount, 1929. Jeanne Eagels, O. P. Heggie, Reginald Owen, Herbert Marshall, Irene Brown, Lady Tsen Mei, Tamaki Yoshiwara, Kenneth Thomson. Producer: Monta Bell; director: Jean de Limur. Adaptation: Garrett Fort, with dialogue by de Limur and Bell, based on the play by W. Somerset Maugham. Shown at Cinecon 40, Hollywood CA, September 2004.

Jeanne Eagels (1890-1929), a renowned stage actress of the 1920s (she appeared with great success in the stage version of Maugham’s Rain), made films for Thanhouser and World Pictures in 1916-1917 (one of the Thanhouser films, The Woman and the World, is available on DVD) and for MGM in 1927, but of the two sound films she made for Paramount, only The Letter is known to survive.

The print is somewhat rough, with the early sound technology (between the dialogue and sound effects, accompanied by strong background “noise,” the sound drops out completely) initially distracting until the ear adjusts.

In spite of this, the fragile beauty of Eagels (only 39 when she died of an apparent drug overdose and advanced alcoholism) and her vulnerable but compelling portrayal of the woman who betrays her husband and murders her lover make this a haunting film that largely overcomes its technical shortcomings.

Herbert Marshall (seen above), who would play the deluded husband in the 1939 version directed by William Wyler and starring Bette Davis, here plays the lover whom Leslie (Eagels) shoots when he confesses that he’s in a relationship with a Chinese woman and that he no longer cares for his high-class, British lover.

This version departs significantly from the Wyler film, and fellow Cinecon attendee John Apostolou confirmed (after an overnight reading of the original novella on which the play and films are based) that de Limur and Bell have largely followed Maugham’s concept.

Gale Sondergaard was memorable as the Chinese lover Li-Ti in 1939, but the casting of an accomplished Chinese actress (Lady Tsen Mei) in the role leads to an equally memorable performance.

In addition, the absence of a moral code in 1929 allowed the inclusion of a scene in Li-Ti’s gambling, drug and prostitution establishment that confronts Leslie with a cage filled with women of “pleasure” that highlights the immoral nature of of the Caucasian woman’s transgressions.

Also, in 1939, Leslie, freed by the courts, was killed in a punishment that society could not impose. Here, she is condemned to remain in a loveless marriage with a man who knows everything about her deceit, in a setting that, like the cage crowded with imprisoned prostitutes, will become her prison.

Some of the audience felt the film ended too abruptly as Leslie is given her sentence by her unforgiving husband and has little screen time to react to it although that could also be seen as heightening her realization of a life without hope of escape.

Tue 1 Dec 2009

SHELLEY SINGER – Following Jane. Signet, paperback original; 1st printing, March 1993.

I suppose everybody in the crime-reading world has wondered — momentarily, at least? — what it would be like to throwaway your day job and become a licensed PI. (Or unlicensed. In a dream world, who cares about technicalities?)

Here’s a book in which Barrett Lake, female, 40 and an unmarried high school teacher, does exactly that. When one of her students suddenly disappears, two weeks after a bloody knife murder in the supermarket where she works, Barrett asks the PI investigating the case (the disappearance, not the murder), if she could be of assistance. Surprisingly — or maybe not — he says yes.

Of course the murder and the disappearance are connected, and Barrett quickly discovers she has a knack for her new job. Not that the case takes much Sherlock Holmesian deductive ability — only slog-it-out detective work. Her mentor, Francis “Tito” Broz, stays intriguingly in the background, and I agree — he’s of far more interest there than if he played any other role in discovering what happened to Jane.

While Shelley Singer is a good writer, she’s not quite good enough to disguise the fact that this first case of Barrett Lake’s is little more than fluff. Nonetheless, in spite of the more-than-hints of the double-edged threats of incest and child abuse, she makes the pages fly by in rapid sequential fashion.

Barrett’s next case will be Picture of David, coming next October.

– This review first appeared in

Deadly Pleasures, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 1993 (very slightly revised).

The Barrett Lake series:

1. Following Jane (1993)

2. Picture of David (1993)

3. Searching for Sara (1994)

4. Interview With Mattie (1995)

« Previous Page