March 2010

Monthly Archive

Mon 22 Mar 2010

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Captive Audience.” An episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (Season 1, Episode 5). First air date: 18 October 1962. James Mason, Angie Dickinson, Arnold Moss, Ed Nelson, Roland Winters, Sara Shane, Bart Burns. Teleplay: Richard Levinson & William Link, based on the novel Murder off the Record (1957) by John Bingham. Director: Alf Kjellin.

Victor Hartman (Arnold Moss) publishes mystery novels, but even so he’s unprepared for what’s been developing for the past few days. Victor has been receiving tape recordings from a prospective author named Warren Barrow (James Mason) in which Barrow may be revealing his plans to exact revenge on Janet West (Angie Dickinson) for trying to frame him for murder — OR what he’s saying on the tapes might just be notes for a novel he hopes to place with Victor.

Victor is unsure and calls in Tom Keller (Ed Nelson), one of his best mystery authors. Is Barrow really planning murder, or is he just floating ideas for a novel? Because, if Barrow IS serious, something has to be done — and fast ….

Altogether, the now legendary but then struggling to get established Richard Levinson and William Link were responsible for five Alfred Hitchcock Hour episodes, and not a bad one in the bunch: “Captive Audience”; “Day of Reckoning”; “Dear Uncle George”; “Nothing Ever Happens in Linvale”; and “Murder Case.”

Another Alfred Hitchcock Hour episode, “The Tender Poisoner,” was also derived from a John Bingham novel.

Hulu: http://www.imdb.com/video/hulu/vi1490550809/

Mon 22 Mar 2010

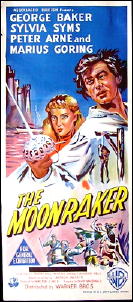

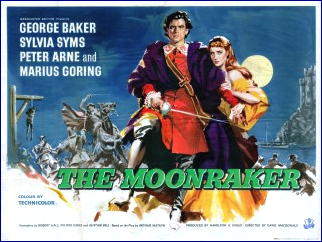

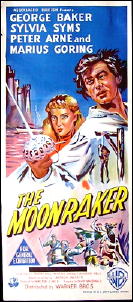

THE MOONRAKER. Associated British Picture Corporation, 1958. George Baker, Sylvia Syms, Marius Goring, Peter Arne, Clive Morton, Gary Raymond, Paul Whitsun-Jones, John Le Mesurier (Oliver Cromwell). Based on a play by Arthur Watkyn. Director: David MacDonald.

A “moonraker” is a smuggler who drops his contraband goods into coastal waters then rakes them up again in the moonlight.

I hope I have that right. If not, those of you who live in England, please do correct me on this — or anything else in this review I might happen to get wrong in the rest of what follows. British history is not necessarily my strongest suit.

The movie begins with the Moonraker (Anthony Earl of Dawlish, played quite handsomely by actor George Baker) riding by horseback in a purple tunic though open meadow land, green wooded areas, down the cobbled streets of a small town at night, then into open land again till we see in the near distance the outline of the circle of standing stones that make up the national monument called Stonehenge.

The next scene purports to take place within those same stones, but I’m not so sure. I suppose the film crew may have been allowed to do so? In any case, it is there that Dawlish meets Charles Stuart, whose father Charles I had recently been overthrown (and executed) by Oliver Cromwell.

It is the Moonraker’s task to ensure the safe passage of the would-be king to France, an event which of course actually happened, though the Moonraker’s role is, as I understand it, quite fictitious.

However, this dates the time that this movie takes place exactly: 03 September 1651. Robin Hood, another British folk hero that even those here in the US have heard of, came along much earlier, the 12th century A. D. and the time of Richard the Lionheart. Just to put events in perspective.

Here in the US as kids (probably not so much any more) we played a lot of Cowboys and Indians, and Good Guys and Bad Guys. Did boys in the UK play Robin Hood and His Merry Men very often? I’m guessing, but probably more than they did Cavaliers (Royalists) and Roundheads (Cromwell’s men).

In any case, it is the strife between the latter that this movie is about. Being based on a play, much of it takes place not in the open (other than the aforementioned opening credits) but in the confines of a small inn along the coast, where Charles Stuart is to begin his voyage by sea to France and his temporary exile.

Complicating matters, for the sake of a story, a girl (Sylvia Syms) who is betrothed to one of Cromwell’s high ranking officers is forced to confront both Dawlish and her own beliefs face-to-face. Romance wins out, but will there be the time and the place for it to bloom further?

There is, of course, much swordplay and other acts of derring-do that also take place, all very well done, in beautiful Technicolor. But while the movie is entertaining from beginning to end, the story itself just isn’t solid or meaty enough to stay in one’s memory for very long. Perhaps it’s more significant and means more in England than it does here?

Mon 22 Mar 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider & Bill Pronzini:

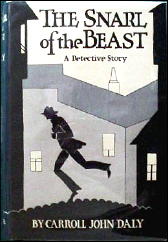

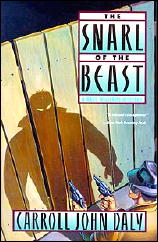

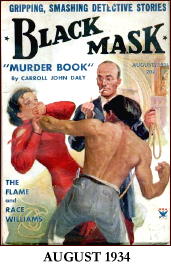

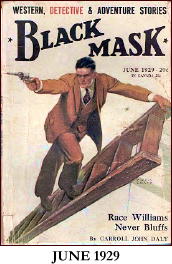

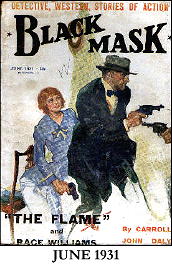

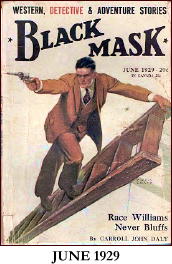

CARROLL JOHN DALY – The Snarl of the Beast. Edward J. Clode, 1927. Previously serialized in Black Mask, June-July-Aug-Sept, 1927. Hardcover reprint: Gregg Press, 1981. Trade paperback reprint: Harper Perennial, 1992.

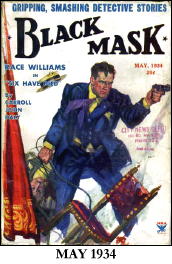

Carroll John Daly was one of the fathers of the modem hard-boiled private eye, a primary influence on such later writers as Mickey Spillane. His style and plots seem dated today, but the presence of his name on the cover of Black Mask in the Twenties and Thirties could be counted on to raise sales of the magazine by fifteen percent.

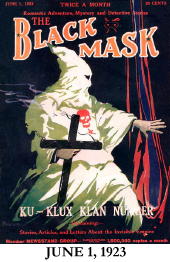

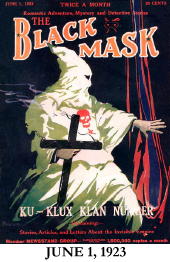

Daly’s major contribution was Race Williams, the narrator of The Snarl of the Beast and the first fully realized tough-guy detective (his first appearance, in the June 1, 1923, issue of Black Mask, preceded the debut of Hammett’s Continental Op by four months).

Williams was a thoroughly hard-boiled individual. As he says of one criminal he dispatches, “He got what was coming to him. If ever a lad needed one good killing, he was the boy.” Williams doesn’t hesitate to dole out two-gun, vigilante justice.

The Snarl of the Beast has an uncomplicated plot: Williams is asked by the police to help track down a master criminal known as “the Beast” and reputed to be “the most feared, the cunningest and cruelest creature that stalks the city streets at night.”

Williams is willing to take on the job and to give the police credit for ridding the city of this menace, just as long as he gets the reward. Along the way he meets a masked woman prowler, a “girl of the night,” and of course the Beast himself.

Daly is not known for literary niceties — his style can best be described as crude but effective — yet there is a certain fascination in his novels and his vigilante/detective.

Characterization is minimal and action is everything. “Race Williams — Private Investigator — tells the whole story. Right! Let’s go.”

Race Williams also appears in The Hidden Hand (1929) and Murder from the East (1935), among others. Daly created two other series characters, both of them rough-and-tumble types, although not in the same class with Williams: Vee Brown, hero of Murder Won’t Wait (1933) and Emperor of Evil (1937); and Satan Hall, who stars in The Mystery of the Smoking Gun (1936) and Ready to Burn (1951), the latter title having been published only in England.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Comment: For a long expository commentary of the book as well as the author, see Mike Grost’s Classic Mystery and Detection website. Included is a breakdown of the novel into its singular parts as they appeared in Black Mask magazine.

Sun 21 Mar 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

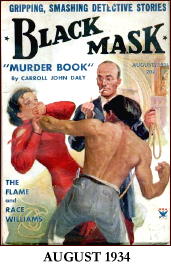

CARROLL JOHN DALY – Murder From the East. Frederick A. Stokes, hardcover, 1935. Previously serialized (as individual stories) in Black Mask, May-June, August 1934. Paperback reprint: International Polygonics, 1978.

Some books have everything — or nearly everything. Murder From the East is one of those. It has a bit of everything — the yellow peril, beautiful adventuresses, and tough guy private eyes.

And as the latter goes, there was never anyone tougher than Race Williams. And if you don’t believe it, just ask him.

“I just wanted to be sure that both your hands were occupied and that you were Race Williams. So — take that.”

His right hand, that was under his jacket, flashed into view. For the moment the hard square surface of a black automatic showed; jerked up so that I looked down the blue barrel of a German Luger.

Hard, red knuckles tightened and showed white. And — I shot him five times. Five times smack in the stomach, before he could ever squeeze the trigger.

Surprised? He was amazed.

So are we. But we shouldn’t be. Race Williams is the first private eye. True, Daly’s own Three Gun Terry Mack beat Race to the game, but Terry wasn’t a private eye, or a least never identified himself as one. He was an adventurer like Gordon Young’s tough gambler Don Everhard.

Race is the first of his breed (not the first private detective, but the first in the hard-boiled mode) making his debut in the Ku Klux Klan issue of The Black Mask in “Knights of the Open Palm.” Some of the stories were pro Klan — Daly’s was anti.

In Murder From the East Gregory Ford, who runs the biggest private detective agency in the city, is working for the government, and wants to hire Race to knock off a gunman who is gunning for Race anyway. But Race isn’t having any.

“Same old Race,” he nodded. “Still trying to pose as a detective and not as a gunman.”

But before the day is over the gunman has run down Race and met his just end. Then the man who hired the gunman shows up in Race’s office.

Tall, thin, slightly bent at the shoulders and dressed to play the Avenue …His face! Well, it was pointed, with a sharp but certainly not protruding chin. I don’t know if it was the color of his skin or the peculiar narrowness of those yellowish brown eyes that gave the impression he was Oriental.

His name is Count Jehdo, and he turns out to be from Astran, a country that is making trouble in Europe and Asia. He’s also involved in the “Torture Murders” the papers are screaming about.

Pretty soon Race is in the pay of the General, the man behind Gregory Ford, and the trail leads Mark Yarrow, the man behind the torture murders and Astran’s crimes but even he doesn’t know about the Number 7 man, the General’s man inside the organization, and Race’s job is to destroy Yarrow while the Number 7 man brings down Jehdo.

Then, who should show up but —

“Florence!” I said. “Florence Drummond — the Flame!”

The Flame and Race have been at this game for a while. She’s up to her neck in this new game and wants Race out of her way.

“This racket,” she nodded and her lips were very thin; very set. “A billion dollar racket!” She came to her feet, walked across the room, pushed aside the curtains by the window, and stood there a moment. There was sarcasm in her words. “I was always one for romance, Race. Let us say a man took my hand, bent forward, kissed it and promised that the day would come when I would sit in the palaces of those who ruled the world.”

But she has taken on more than a lover. She is now the Countess Jedho.

The rest of the book precedes in a hail of gun smoke as Race thins the numbers of the organization and generally makes a nuisance of himself. He’s captured and tortured, but escapes thanks to the Flame and eventually smashes Yarrow and Jehdo and reveals the Number 7 man.

“You made use of what you always make use of. It’s not your head; it’s the animal in you. The courage in you; the thing that drives you on. You’re licked — licked a dozen times, over and over. Everybody knows it but you! No, it’s not your head.”

Much has been written about Daly’s shortcomings as a writer, and most of it is true, but what is also true is that he wrote at a sort of white hot level straight from the hip, like the hot lead pouring from is blazing .45’s, and for all the melodrama, cliches and corn, there is a conviction to his best work that few writers ever managed.

In terms of style and literary considerations he is a pale shadow of Hammett and Chandler, and he could never plot or even created characters as well as Erle Stanley Gardner, but he was the most popular writer at the famed Black Mask, and his name on the cover drove sales up every month.

Time passed Daly and Race by. For a time his tales of Satan Hall, a Dirty Harry style cop, surpassed Race, and Race eventually fell from the Mask to lesser pulps as Daly’s career sagged. By his death in the 1950’s his books couldn’t find an American publisher.

For a time Race Williams and Carroll John Daly were kings of the hard-boiled private eyes. If they lacked the graces of the better writers they still offered their own brand of thrills and action, and in their wake marched the Dan Turner’s, Mike Hammer’s, and Shell Scott’s that followed. If nothing else Daly influenced Mickey Spillane, and in Spillane had a lasting impact on the genre.

Race and his creator are fairly insubstantial figures now, but once they were giants, and traces of their footprints still leave a trail. Park a few of your critical judgments and you can still find a good deal of enjoyment in Race’s adventures.

You may not applaud the writing, but you are likely to stay for the sheer entertainment. Perhaps more than many of the better writers from Black Mask, the true voice of the pulps thunders in the exploits of the one of a kind Race Williams.

Sat 20 Mar 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

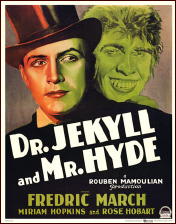

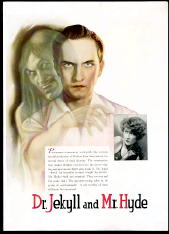

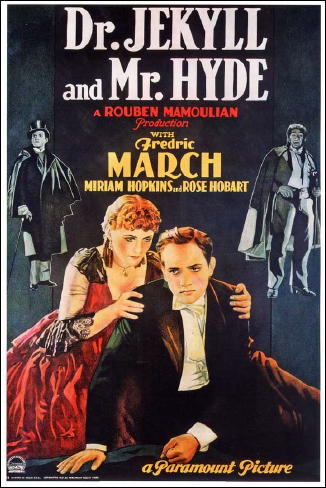

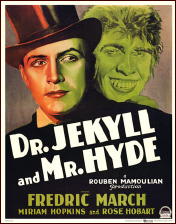

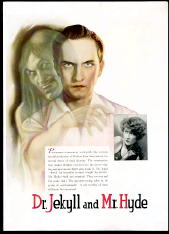

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE. Paramount Pictures, 1931. Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Holmes Herbert, Halliwell Hobbes, Edgar Norton, Tempe Pigott. Screenplay: Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath, based on the story by Robert Louis Stevenson. Director: Rouben Mamoulian.

In 1931, two films were released that are still being shown in theaters and on television: James Whale’s Frankenstein and Tod Browning’s Dracula. Their great popularity initiated the horror cycle of the thirties.

A third film was released that year whose subject was, like Frankenstein, the creation by a brilliant, eccentric scientist of a creature who threatens his creator’s life and sanity, but Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is director Rouben Mamoulian’s only horror film, and it has languished in relative obscurity,

The film’s fluid, imaginative camera work, for which Mamoulian was noted, allies it to the best horror/fantasy films of the period as well as to the innovative musicals that were Mamoulian’s chief subjects in his long Hollywood career. It may be of some interest to note, in this respect, Whale’s direction of the 1936 Showboat, and to suggest that in their free use of non-realistic elements, the musical and horror films of the thirties are not unrelated.

Mamoulian’s adaptation, like the other film versions of Robert L. Stevenson’s novella, places great emphasis on the laboratory and transformation scenes and, unlike the source, doesn’t attempt to conceal the nature of Hyde’s identity from the audience.

(In Stevenson’ s story, Hyde is the evasive criminal whose secret Mr. Utterworth, the lawyer-investigator wryly calling himself Mr. Seek, sets out to uncover, making of the adventure at once a morality and a detection tale.)

The laboratory is the conventional workshop of the thirties’ horror film, a classical locus that is at its most poetic and imaginative in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein. It is also a dramatic stage which gives some slight plausibility to the drug-induced emergence of the Hyde personality.

Mamoulian’ s principal interest is probably not in the horrific or suspenseful elements of the story, although his film is lacking in neither of these. His Hyde — a curious Simian-Negroid creation that may strike some viewers as a rather blatant ethnic stereotype — is certainly repulsive enough, but I think the director’s real subject is the consequences of the release of all inhibitions, his Hyde brooking no interference with any of his immediate needs and desires.

This is most evident in the careful portrayal of the apparent distinction between Jekyll, the staid Victorian lover (even if unconventional scientist), and Hyde, the sensual, brutal lover whose pleasure is in a sadistic inflicting of pain on his mistress. And it is in the tactful but powerful depiction of Hyde’s relationship with his mistress (marvelously played by Miriam Hopkins) that the originality of this film in its relation to the horror film lies.

The male/female relationships in the Hollywood horror films of the period tended to be chaste, unlike the franker treatment in other genre films: the rampant visual/sexual puns in the Busby Berkeley musicals, the poetic physicality of the Tarzan/Jane relationship in the first two MGM Weismuller/O’Sullivan films and Kong’s famous — and later edited — undressing of Fay Wray in King Kong.

If one of the cherished memories — and cliches — of the monster chasing and sometimes carrying the heroine to a possible but never realized fate worse than death, the sexual play in these films is relatively tame.

Not so in Mamoulian’s Jekyll. One of the best sequences — still memorable and unsettling is of Hyde’s unexpected return to his mistress’s chambers and his subsequent vicious teasing before he strangles her in a grim and deadly parody of the sexual embrace.

It has often been said that the Horror of Dracula (Hammer Films, 1957) made explicit the eroticism of the vampire myth; what should also be pointed out — and perhaps for its irony — is that in the year that Browning’ s Dracula presented the classic version of the gentleman vampire, Mamoulian’s night-creature (like Dracula, freest and most powerful in his mistress’ s bedroom) tortured and teased and sexually abused his lover a way that the “mainstream” horror film would only dare to follow a quarter of a century later.

The classic horror film has its narrative source in Victorian taboos and the way in which they are circumvented by the monster created in the laboratory or the grave. The vampire is the dark lover, the sensual bringer of pleasure and death, so unlike the correct, cardboard hero.

In Mamoulian’s film, the hero and the villain inhabit the same body. His Jekyll (Fredric March) has been criticized for his wooden playing, but what has not to my knowledge been pointed out is the way in which, as Hyde increases in strength, Jekyll comes to resemble him.

There is a striking scene when Jekyll returns home, free he thinks of Hyde but dressed in the cape and top-hat affected by his other self and in his extravagant gestures more like the exuberant Hyde than the controlled scientist.

But, then, Hyde was never far from Jekyll as the scientist pursued his obsession with the separation of the dual self, an obsession whose consequences are finally as destructive as Hyde’s natural genius for evil.

Early in the film, before Jekyll effects his first transformation, the good doctor treats a patient in her room. This patient is Ivy, the prostitute Hyde will pursue and kill, and as Jekyll takes his leave of her after they are surprised by his friend Lanyon in a passionate embrace, Ivy whispers seductively, “Come back,” and languorously, voluptuously moves her bare leg enticingly back and forth.

Mamoulian superimposes the shot of her leg and the echo of her invitation over the following scene as the supposedly blameless Jekyll and his friend walk away from the apartment. Sex and science are both seductive siren calls, and the breaching of limits is fatal for both scientist and lover.

Call Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde a morality play, a scientific romance, a monster film with many of the genre’s conventions, a psychological flirtation with the mysteries of the self, this superbly crafted and haunting film is an artful extension of the possibilities of the horror film, and it has a power to disturb that still sets it apart from most other genre films of its time.

� This review first appeared in

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 7, No. 1, January/February 1983.

Sat 20 Mar 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

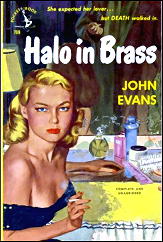

HOWARD BROWNE – Halo in Brass. Dennis McMillan, trade paperback, 1988. Originally published as by John Evans: Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1949; paperback reprint: Pocket #709, July 1950.

Another Eastern writer besides Steve Fisher who hit it big in the movie and television industry of Hollywood was Howard Browne, whose movie credits included The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and who wrote television shows like Mission Impossible and The Rockford Files.

Dennis McMillan Publications has recently reprinted one of Browne’s best books, Halo in Brass, which he originally published in 1949 as by John Evans.

As Evans, Browne wrote a small series of books about Chicago private eye Paul Pine, and each is memorable. Brass concerns Pine’s efforts to find a young woman who disappeared after she left Nebraska to live in Chicago.

It explores themes not generally written of in the mysteries of its era, but don’t read Browne-Evans just because he was ahead of his time. Read him because he was a remarkable story teller, one who was imaginative and who created one of the best first-person narrators in the long history of the private detective novel.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 4, Fall 1988

(slightly revised).

Sat 20 Mar 2010

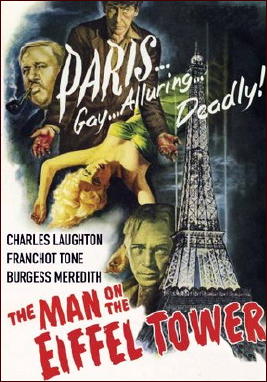

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

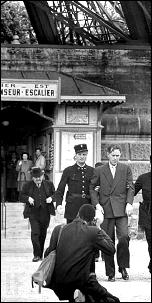

THE MAN ON THE EIFFEL TOWER. RKO, 1949. Charles Laughton (Inspector Jules Maigret), Franchot Tone, Burgess Meredith, Robert Hutton, Jean Wallace, Patricia Roc, Belita.

Screenplay: Harry Brown, based on the novel A Battle of Nerves (La Tete d’un Homme, Paris, 1931) by Georges Simenon. Director: Burgess Meredith.

The Man on the Eiffel Tower can be picked up on DVD for about a buck at bargain stores, and it’s well worth the effort. Burgess Meredith took a one-time shot at directing this and stars as a myopic scissors-grinder set up to be the patsy when Franchot Tone commits murder-for-hire.

Tone’s scheme works with creepy efficiency (A scene of Meredith stumbling about the murder scene looking for his smashed glasses prefigures the well-known Twilight Zone episode.) and Burgess seems headed for the Gallic equivalent of Slice-o-Matic till Inspector Maigret intuits the solution and sets about putting things right

The plot moves swiftly and with some intelligence, but this is basically an actor’s movie — watch it to see Burgess Meredith’s hammy underplaying, or Franchot Tone’s manic-depressive killer, a brilliant Raskolnikov flinging himself up against Charles Laughton’s relaxed, authoritative Maigret/Porfiry, who realizes the only way to resolve the problem is to gently coax a confession from a psychotic.

This felicitous mix of writing (courtesy of Harry Brown) directing and acting doesn’t come along all that often, and it provides here a deal of genuine pleasure for mystery fans and movie lovers like me.

Fri 19 Mar 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

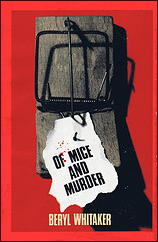

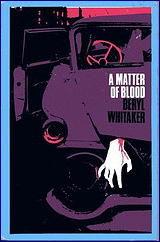

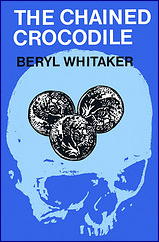

BERYL WHITAKER – Of Mice and Murder. Robert Hale, UK, hardcover, 1967. No US edition.

Ten o’clock on a Sunday morning is a fortuitous hour in most households. There is the prospect of indolence, and a sense of ill staved off. There is a more expansive, more leisurely breakfast than usual: there is the

News of the World. In all save the totally discouraged hope revives, and does not flicker out until approximately six-fifteen.

It is difficult not to expect good things from a novel that begins in such a manner, and Whitaker provides them. Her detective, in this and apparently her three other novels, is John Abbot, a schoolmaster with a private income and criminology for a hobby. Abbot is not a particularly interesting man; thus, paradoxically, he is most interesting.

With no present crime to pique his interest, he is studying the William Herbert Wallace case. He abandons this when his twin sister points out the affair at Turton Caundle, where a human body was burned in place of the traditionally stuffed “Winter Figure.”

Abbot goes to the village to investigate and finds himself becoming equally as, perhaps more, interested in a horrible accident that took place in the village a few months earlier.

Despite the murderer and the motive being evident, the novel holds one’s attention. The light beginning changes to a darker tint as the plot unfolds and Abbot, in his interviews, discovers the solution. Very close to first class.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 3, Summer 1992.

Bibliographic Data: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

WHITAKER, BERYL (Salisbury). 1916-1996. Series Character: John Abbot, in all.

Of Mice and Murder (n.) Hale 1967.

A Matter of Blood (n.) Hale 1967.

The Chained Crocodile (n.) Hale 1967.

The Man Who Wasn’t There (n.) Hale 1968.

Editorial Comments: At the moment, this is all I know about the author. Of her four mysteries, copies of only two of them can be found for sale on the Internet, Crocodile and Mice, with only two sellers offering the latter for sale, one for around $50, the other $120. Out of my league, I’m afraid.

Bill’s review makes the $50 one tempting, though, as he seldom used the phrase “first class” to describe a book. I wish he’d gone into more detail about what he found so enjoyable. It’s tantalizing to read what he has to say and be unable to ask him more.

[UPDATE] 03-22-10. British mystery bookseller Jamie Sturgeon has come across an erroneous entry for the author in Contemporary Science Fiction Authors, included at the editors’ own admission that none of the books she had written at that time were SF.

From the data presented, however, the chronological order of the books has been revised (see above), and the correct spelling of Beryl Whitaker’s middle name (Salusbury) will be noted as such in the next installment of the online Addenda to the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

Beryl Whitaker was born August 8, 1916, the daughter of Charles and Rosamund Colman (originally Collmann). Salusbury was her mother’s maiden name. She was married three times; her third husband was Gerald Whitaker, with whom she had three children. She died, as was previously known, in 1996.

Besides the four mystery novels, Jamie also discovered a short story collected in John Creasey’s Mystery Bedside Book 1974 (1973), the title of which is “Two Birds and a Stone,” which first appeared in London Mystery Magazine. Mrs. Whitaker also promised the editors of Contemporary SF Authors that her next novel would be science fiction, but if the book was ever written and published (and if so, under a pen name) is not known.

[UPDATE #2] Later the same day. In a copy of one of her books, Jamie has discovered a handwritten Thank You note from the author to a friend. Omitting the portions of a personal nature, Mrs. Whitaker says in part:

“I thought I would write thrillers because I didn’t reckon I had the talent to write the stuff I’d really like to. So you see this is why my little crime novels have their serious side, and are in some cases, sad.”

[UPDATE #3] 03-23-10 Thanks to Jamie once again for supplying the cover images you now see.

Thu 18 Mar 2010

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

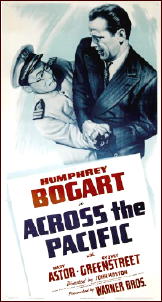

ACROSS THE PACIFIC. Warner Brothers, 1942. Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sidney Greenstreet, Victor Sen Yung, Keye Luke, Charles Halton, Richard Loo, Monte Blue. Screenplay by Richard Macauley, based on a Saturday Evening Post serial “Aloha Means Goodbye” by Robert Carson. Directed by John Huston .

Humphrey Bogart: I never saw anybody like you, you never have any clothes on.

Mary Astor: Well if anyone heard you complaining about it they would put you in a psychopathic ward.

It was inevitable that any follow up to The Maltese Falcon was going to be anti-climactic, which is a shame, because this lighthearted flag-waver has a myriad of charms all its own including the sexual byplay between Bogart and Mary Astor, and Sidney Greenstreet’s treacherous Dr. Lorenz.

And it probably didn’t help that midway through production the Second World War broke out with the very much for real attack on Pearl Harbor, and the plot about a fictional Japanese attack at the same location was suddenly too serious for this lighthearted treatment.

The production took a hiatus while the script was quickly rewritten, and somehow in the transition the title remained unchanged, even though now the ship in question never even reaches the Pacific. (It might also explain some less competent model work than usually seen from the studio effects department.)

Bogart is Rick Leland, a US Army officer cashiered for irregularities with company funds. He heads for Canada hoping to enlist, but they want no part of him, so he determines to sell his services to the Chinese and sets sail on a Japanese ship sailing for Panama and then Yokohama.

On board the ship are Dr. Lorenz (who teaches economics in Manila), his servant, and Alberta Marlowe (Mary Astor)

Humphrey Bogart: Don’t be an innocent bystander; they always get hurt.

who claims to be a simple girl from Medicine Hat out to see the world despite a wardrobe to die for and the sophistication of a woman of the world.

And as you quickly learn, nothing is exactly what it seems. Lorenz managed to get Leland on the ship because he knows of his military background, and Leland is in reality a secret agent, his disgrace a cover designed to lure Lorenz and the Japanese into approaching him.

After a stop over in New York where Victor Sen Yung comes on board as a jive-talking Japanese American sailing East to take over family business interest, Leland and Astor stop a Filipino from assassinating Lorenz.

Humphrey Bogart: How are you doing, angel?

Mary Astor: I think I got pushed in the face by someone. My – My lipstick’s smeared.

Humphrey Bogart: Aww, you look cute.

Mary Astor: And now, if you’ll excuse me, I’ll go to my cabin… and faint.

the good doctor makes it clear he wants information from Leland about Panama’s defenses and is willing to pay for it while Leland romances Miss Marlowe

Mary Astor: I’m not so obsessed with money as you seem to be. I can do without it.

Humphrey Bogart: You stick around with me and you’ll get plenty of practice.

and ingratiates himself with Lorenz.

Humphrey Bogart: (comparing his gun to Lorenz’s) : Mine’s bigger.

Once in Panama, things move fast. Astor disappears, and Greenstreet outwits Leland and gets the plans for the Canal’s air defenses. Leland meets a Chinese at a Japanese theater in Panama where a well staged shootout ensues, and then heads for a plantation that has been mentioned as a place of interest.

There he finds Astor, the daughter of the westerner (Monte Blue) forced to front for the Japanese, and discovers a hidden airfield built in the jungle. It’s December 6th, 1941, and using the information gotten from Leland, the Japanese are going to bomb the Canal to coincide with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Of course they are no match for our hero, who dispatches Victor Sen Yung with a right cross and grabs Richard Loo’s .50 caliber machine gun to shoot down the bomber and take care of the rest.

Back at the plantation Sidney Greenstreet contemplates hari-kiri, but lacks the nerve and Leland arrests him.

Humphrey Bogart: I’m disappointed. All that talk about will and strength.

And as they step outside a formation of American planes flies over:

Humphrey Bogart: Any of your friends in Tokyo have trouble committing hari-kiri, those boys’d be glad to help them out.

No one is arguing that this is the same category as The Maltese Falcon, but it is a remarkably assured and entertaining spy film with dialogue that sparkles and real sexual tension between Bogart and Astor.

This often gets lost among the bigger (and better) films of Bogart and Huston, but deserves to be seen and enjoyed. It’s fast, flip, sexy, and well acted by all concerned.

Maybe we should just be grateful that there are so many great films that this terrific good film gets lost in the shuffle. This tongue-in-cheek thriller is still fresh and smart, and more modern than most similar films of the era.

Note: Huston left to join the war effort and the final scene was shot by Vincent Sherman. And for some reason the two maps showing the Canal in the film are wrong. The one at the end of the film upside down with the Pacific on Panama’s East Coast! I suppose it’s possible the intent was to keep the enemy from using the maps, but you have to imagine the Japanese knew where the Canal was. You wouldn’t think it would be that easy to disguise.

Wed 17 Mar 2010

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

CRIMINAL JUSTICE. BBC, UK. Second series: 5 through 9 October 2009.

Maxine Peake, Denis Lawson, Sophie Okonedo, Steven Mackintosh, Kate Hardie, Nadine Marshall, Matthew Macfadyen, Zoe Telford. Written by Peter Moffat; director: Yann Demange.

This was a highly touted five part series (one hour each, no adverts) shown over five successive nights. It was actually the second under this title, but as I seemed to be the only person who didn’t enjoy last year’s opener, I was fearing the worst.

Actually this story of an oppressed wife who stabs her husband but then refuses to talk about it had some very good scenes and seemed to me to be on a different level that last year’s story.

We saw the progress of the wife through the flawed justice system both through the courts and on remand in the prison system. At times slow moving, and implausible in places, there were enough moving moments to make this worth persevering with.

« Previous Page — Next Page »