June 2011

Monthly Archive

Sun 5 Jun 2011

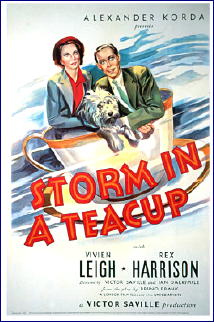

STORM IN A TEACUP. United Artists, UK/US, 1937. Vivien Leigh, Rex Harrison, Cecil Parker, Sara Allgood, Ursula Jeans, Gus McNaughton, Lee Strasberg. Based on the play Sturm im Wasserglas by Bruno Frank; author of the Anglo-Scottish version: James Bridie. Directors: Ian Dalrymple & Victor Saville.

Vivien Leigh is beautiful, almost exquisitely so, Rex Harrison is lean and lanky, with ever so often a wicked glint in his eyes. Other than Technicolor, what more could you possibly want in a movie?

An English manor overflowing with dogs, you say, leashed as part of a protest against a Scottish provost who talks about the welfare of the little man but who sadly forgets when it is time to put it into practice – and hilariously so? ’Tis done, and more.

Vivien Leigh is the good Provost’s daughter, and Rex Harrison is the roguish but idealistic young reporter from England who pokes a stick in the Provost’s spokes when the latter refuses to hear a plaintive plea from Mrs. Hegarty (Sara Allgood) for leniency.

It seems the good lady has failed to pay a licensing fee for her mongrel dog Patsy, and it is off to the pound for the latter.

Harrison’s subsequent newspaper story is the storm in a teacup that grows and grows from there. Complicating matters is that Harrison also has his eye on Vivien Leigh, and while she pretends otherwise, so does she, only vice versa.

This is a good old-fashioned comedy, done English style, with plenty of wit, subtle and not so subtle – and not only that, but dignity under adversity and pressure: witness the Provost stalwartly leading his entourage straight through the mob of local townsfolk that was jeering him so rudely only moments before. This happens not very often in the US, where the back door is the more common way out.

Sun 5 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

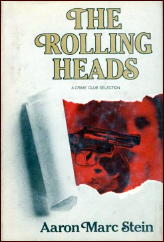

AARON MARC STEIN – The Rolling Heads. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1979. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, July 1979.

It shouldn’t be revealing too much to say that the heads mentioned in the title are really of cabbages, but what they’re doing blocking a French highway will be left to stay part of the mystery.

Matt Erridge, by occupation an engineer, finds a girl he’s delighted to take with him on a tour of French castles, but as it happens, she has a jealous boy friend, and the latter has kidnapping, if not murder, on his mind.

Erridge knows his way around all parts of the world, and his adventures continue to keep Stein, his chronicler, busy at the typewriter. Even though a great deal of puzzled detective work takes place, this is still essentially an action story. No actual detection required.

Rating: B minus.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov/Dec 1979 (very slightly revised). This review also appeared earlier in the Hartford Courant.

[UPDATE] 06-05-11. Besides being very prolific under his own name, Aaron Marc Stein also wrote many mysteries both as both George Bagby and Hampton Stone. Under any of the three names, he’s always been one of my favorite authors. If you use the search box somewhere here on the right, you’ll find many of his books already reviewed on this blog.

I wish this particular review weren’t so short, but I was relatively new at the Courant at the time, and shorter reviews were all they wanted from me. Too bad. This review, well under 200 words, doesn’t remind me a whole lot about the book, just enough to make me want to read it again, the next time it surfaces.

Sat 4 Jun 2011

THE MYSTERIES OF THE MAKING OF

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE

by Michael Shonk

This is Part Two of a series of posts about the vintage TV private eye series The Cases of Eddie Drake. If you haven’t already done so, click here to read Part One, in which the show itself is discussed: the actors, actresses, and the program’s antecedent on radio, The Cases of Mr. Ace. In the radio version George Raft played the role of PI Eddie Ace.

Part One ended with some questions that have yet to be answered. Virtually all sources agree on the history of TV version of The Cases of Eddie Drake, but are they right? Today it is accepted CBS filmed nine episodes in 1949 and then never aired it. In 1952, DuMont filmed the final four episodes and aired the series March 6, 1952 through May 29, 1952.

Internet Archives states that NBC aired the series June 4, 1951 through August 27, 1951, all 13 episodes. If true why would DuMont film four episodes and let NBC stations show it almost a year before it aired on the DuMont network?

None of it makes any sense.

Over at Google e-bookstore, I found an edited archive of Billboard magazine available. Billboard covered the television business during the years in question, 1948 through 1952.

The August 28, 1948 issue of Billboard had a news item about “one of the biggest tele-pix deals on record.” CBS had agreed to pay $300,000 “for a series of three 13-episode half-hour films”.

It added, “Series will be tagged The Cases of Eddie Drake scripted by Jason James, who penned the original Eddie Ace.” The news item further stated CBS owned half of the series with IMPPRO Productions. The budget for each episode was $7,500. Plans were to shoot four episodes simultaneously in a 10-day period. Filming would be in Los Angeles and use 35mm film.

The November 20, 1948 issue reported that IMPPRO VP Harlan Thompson would deliver the first five episodes of Eddie Drake to CBS executives in New York during the week of November 13th. Four other episodes were being finished in editing. Filming for the four remaining episodes of the 13 episode series would start Wednesday, November 17, 1948.

It is important to know that there was concern in 1948 that there were not enough writers to make enough TV dramas to fill the needs of all the TV stations. Any type of drama was in huge demand.

Nearly all network series, for budget reasons, were live or kinescoped. During this period TV Film was used mainly for local syndicated programs. TV Film allowed advertisers to shop TV series wherever they wanted, and the local stations to program the shows whenever they wanted.

Because Eddie Drake was a TV Film series, I don’t believe CBS ever intended it to be a network series, but instead always planned for it to be syndicated to local stations. Could Eddie Drake have aired in 1949?

Billboard suddenly has nothing to say about The Cases of Eddie Drake until 1951. However, this does not mean the series was shelved. Between 1948 and 1952 was a wild period for television.

In 1948, radio was still King, but TV was making it sweat. TV stations were popping up all over the country. Things were happening too fast, it was making people nervous. So nervous, the FCC put a temporary freeze on new TV stations. The freeze was supposed to last six months, but lasted instead until 1952.

The national media at that time paid little attention to local TV programming and syndication. It is possible Eddie Drake was on the air in 1949 and ignored except in small local markets.

By 1952, TV Film syndication had become a highly successful business. Everyone, including CBS and NBC, were selling non-network syndicated programming. CBS Television Film Sales had become a separate unit from CBS-TV network. According to Billboard, in 1952 The Cases of Eddie Drake was one of CBS Television Film Sales syndicated series.

While I have found no other reference suggesting that NBC stations ever showed Eddie Drake, I did find one item of interest. In the August 25, 1951 issue of Billboard, the local syndication coverage mentioned Virginia Dare Wines would sponsor The Cases of Eddie Drake on WENR-TV, Chicago starting September 7, 1951. This meant Eddie Drake was syndicated and on the air at least six months before DuMont aired the series.

Patricia Morison was in the first nine episodes, but then replaced by Lynne Roberts. Why?

Nine episodes had been filmed when CBS met with producer Harlan Thompson. Could CBS have asked for a casting change before IMPPRO filmed the final four episodes in November 1948? Why would CBS shelve any TV series during a time when there was a huge demand for any TV drama?

We need to see an episode with Lynne Roberts. As far as I know only one episode still exists, “Shoot The Works” which co-starred Patricia Morison. However, according to the Paley Media Center website, it has a copy of “Sleep Well Angel”, an episode with Lynne Roberts. Comparing the episodes should help give us some answers about the past of Eddie Drake. Are the writer, director and producers the same? It is unlikely all would return after a three-year layoff to film four episodes for DuMont. Has the set for Eddie’s office changed? Does Eddie still drive his three-wheel 1948 Davis Divan? What is the copyright date on the screen?

Finally, it is commonly thought The Files of Jeffrey Jones first aired in 1954 and was somehow connected to Eddie Drake. But Jeffery Jones first aired in 1952 and had no connection to Eddie Drake beyond star Don Haggerty and CBS Television Film Sales. Though in 1955, CBS Television Film Sales offered Eddie Drake as a “bonus arrangement” to any station buying Jeffrey Jones.

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE. Syndicated; 13 episodes at 30 minutes each. CBS Television Film Sales. IMPPRO Productions. Produced by Harlan Thompson and Herbert L. Strock. Directed: Paul Garrison. Written: Jason James. Star: Don Haggerty. (Billboard, February 27, 1954)

THE FILES OF JEFFREY JONES. Syndicated; 39 episodes at 30 minutes each. CBS Television Film Sales. Lindsley Parsons Production. Produced: Lindsley Parsons. Directed: George Blair and Lew Landers. Star: Don Haggerty (Billboard, May 28, 1955)

While some Pop Culture historians take it personally when their findings are questioned, I am the opposite. If you have any questions or information to correct any mistakes I might have made, please post them in the comments.

The years between 1946 and 1952 were when network television truly began. We need to know the facts and understand the context in which those facts existed, before we can understand the true history of television.

Fri 3 Jun 2011

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE – PART ONE

A Review by Michael Shonk

THE CASES OF EDDIE DRAKE. TV series. Thirteen 30 minute episodes. Created and written by Jason James (Jo Eisinger). Cast: Eddie Drake: Don Haggerty, Dr. Karen Gayle: Patricia Morison (nine episodes), Dr. Joan Wright: Lynne Roberts (four episodes), Lt. Walsh: Theodore Von Eltz. Produced by Harlan Thompson and Herbert L. Strock. Directed by Paul Garrison.

Eddie Drake was your typical hardboiled PI of the time, from his attitude to his roving eye for anything in a skirt. Eddie shared the details of his cases with beautiful Dr. Karen Gayle, perhaps television’s first psychologist. She was writing a book about criminal behavior and wanted the point of view of a hardboiled PI. After nine episodes, Dr. Joan Wright replaced Dr. Gayle.

The Cases of Eddie Drake began on radio as The Cases of Mr. Ace. George Raft was New York PI Eddie Ace who each week sat down and told Dr. Gayle about his latest case.

Note that the film Mr. Ace (1946) starring George Raft as political kingmaker Eddie Ace had no connection to the radio series.

The relationship between Ace/Drake and Doctor Gayle was different in the radio and television versions. On radio, Dr. Gayle makes it plain she is willing to get personal, while Ace has problems asking her out for dinner. On TV, Drake does everything but chase her around the desk.

The body count was high for both Ace and Drake. Dr. Gayle once noted Eddie’s cases were full of “heaters and cadavers.” Of the three surviving radio stories, Eddie’s cases all ended in gunfire and nearly everyone dead.

Behind both series was Jason James, Edgar award winner (with Bob Tallman for the radio series Adventures of Sam Spade in 1947). Heavily influenced by the writings of Dashiell Hammett, the scripts for Ace and Drake never came close to the quality of James’ work on Spade. But then, Raft and Haggerty were no Duff or Bogart.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

THE CASES OF MR. ACE. Radio. Syndicated. Aired June 4, 1947 through September 3, 1947 on WNEW-New York (*). Paragon Radio Production. 30 minutes. Cast: Eddie Ace: George Raft. Written, directed and produced by Jason James (Jo Eisinger).

“Key to a Booby Trap,” June 4, 1947 (aka “Key to Death”)

Tough guy Ace meets Dr. Gayle and tells her about his latest case. A Frenchman confesses to Ace he killed a man who was bothering his wife. He pays Ace to give a key to his lawyer. The lawyer says the Frenchman is innocent, but his wife is eager to watch her husband die. When the key leads to more death, Ace wants to know why.

“Man Named Judas,” June 25, 1947 (aka “Lost Package”)

Ace is hired to deliver a package but fails. When he returns, he finds the client dead. Then third-rate versions of Cairo and Gutman (Maltese Falcon) arrive wanting the last surviving Judas coin.

“Watch and the Music Box”

Only the last half survives. Script was reused as the Eddie Drake episode, “Shoot The Works”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

One episode of Eddie Drake remains available to be viewed on the internet or DVD.

“Shoot the Works.” (First aired date unknown.)

Drake tells Dr. Gayle about his recent case. A woman hires Drake to get her watch back. It had been stolen during a gambling club robbery where a man was killed. She had been with a man who was not her husband, and she is worried, if the police recover the watch, her husband will find out.

Drake visits the club owner, a wild Russian “Prince” who is desperate for Drake to find the woman he loves, a woman he has only seen on a nickel peep show. The bodies begin to pile up when the thief arranges to sell the watch to Drake.

After the story, Eddie takes the beautiful Doctor out for drinks. There the actors break character and tell the audience the episode’s credits.

Much like other syndicated TV Film programs of the time, Eddie Drake was nothing special beyond mildly entertaining. Eddie was a character who was interchangeable with the countless other hardboiled PIs of the time.

The creative idea of a psychologist using the point of view of a hardboiled PI for a book about criminal behavior was wasted as a weak framing device to tell typical hardboiled mysteries. The acting was professional but average, never adding anything new or of depth to the characters or stories. The only truly unforgettable part of Eddie Drake was “Dave,” Eddie’s new car, a three-wheel 1948 Davis Divan.

Which leads us to Part Two, coming soon: “The Mysteries of the Making of The Cases of Eddie Drake.”

Common knowledge about the TV series today is that CBS filmed nine episodes in 1949 and then never aired it. DuMont is supposed to have filmed the final four episodes and broadcast all thirteen in the period from March 6 to May 29, 1952. Before that, according to one source, NBC aired the series between June 4, 1951 through August 27, 1951 (13 weeks).

Did CBS shelve the series for three years? Why did Lynne Roberts replace Patricia Morison after nine episodes? Why would DuMont film the final four episodes then wait six months to show it? When did Eddie Drake first air, 1949 or 1951? How much of what is currently believed about this series wrong?

SOURCES:

Billboard archives available for free reading at Google e-bookstore.

Episodes of The Cases of Eddie Ace are available to listen to at various sites on the internet. I did my listening at Internet Archives (archive.org)

(*) New York Times radio logs can be found at www.jjonz.us/RadioLogs

The television episode “Shoot the Works“ is also available around the internet and on DVD, Best of TV Detectives – 150 episodes. I watched it at Internet Archives and Classic Television Archives (which also has an episode log).

http://www.archive.org/details/The CasesOf EddieDrake-ShootTheWorks1949

http://ctva.biz/US/Crime/EddieDrake.htm

Thu 2 Jun 2011

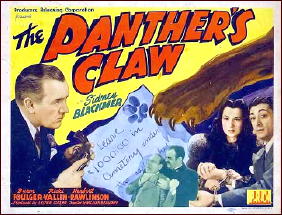

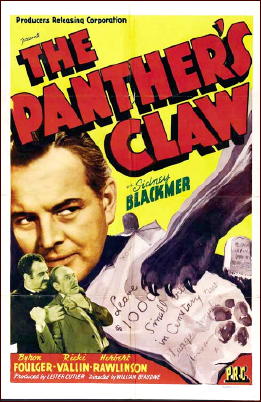

THE PANTHER’S CLAW. Producers Releasing Corp. (PRC), 1942. Sidney Blackmer (Police Commissioner Thatcher Colt), Ricki Vallin (Anthony “Tony” Abbot), Byron Foulger, Herbert Rawlinson, Barry Bernard, Gerta Rozan, Joaquin Edwards. Based on a story by Anthony Abbot (Fulton Oursler). Director: William Beaudine.

Thatcher Colt was a character who appeared in a number of detective novels by Anthony Abbot in the 1930s and early 40s, beginning with About the Murder of Geraldine Foster in 1930. According to IMDB, though, The Panther’s Claw was based on the short story “The Perfect Crime of Mr. Digberry.”

On the other hand, the American Film Institute says it was based on the story “Shake Hands with Murder.†But since Mr. Digberry is definitely a character in Panther’s Claw, and Shake Hands with Murder is a totally different (non-Thatcher Colt) film made by PRC in 1944, we’ll say IMDB has the advantage here.

There were two earlier film adaptations of Thatcher Colt novels, both of them with Adolphe Menjou in the starring role: The Night Club Lady (1932) and The Circus Queen Lady (1933).

I’ve seen neither of these, but I think the solid, mostly no-nonsense acting of Sidney Blackmer fits the role of the definitely hands-on police commissioner better. In fact AFI states that Panther’s Claw was intended to be the first in a series. If so, the plans did not work out, as there never was a follow-up.

Blackmer was the leading man, with top billing and all that goes with it, but believe it or not, it was Byron Foulger, the unlikeliest of movie stars, who gets the majority of the screen time. He plays Mr. Digberry, a mild, meek, milquetoast of a man (meaning that Foulger was perfect for the part) with a 180 pound wife and five daughters. (They’re out of town, though, throughout the movie. We only get to see Digberry’s reaction whenever he realizes that they’ll be back soon.)

We see first meet Digberry as he’s being caught by the cops sneaking out of a city cemetery at night. It seems he’s received a note that requested he leave $1000 on a gravestone, signed by “The Panther” along with a paw print in ink at the bottom.

The cops get a big chuckle out of this, as well as the audience, even though Digberry is not the only one to have received such a message. There is more to the case, though, as the “Panther†portion of which is quickly solved, and as it happens, there are more strings to the bow of the greatly bewildered and befuddled Mr. Digberry than first meets the eye.

There is a murder to be solved, in other words, that of a female opera singer … and I won’t tell you more, but there is a lot more plot in this 70 minute movie than there is in a many a present-day double-the-running-time extravaganza with lots of action and special effects, none of which are present here. The Panther’s Claw was produced on what is obviously a bare-bones budget.

While the movie’s still running, it is difficult to follow the business of the wigs and the rival wigmakers, or how important it is, but it all makes sense in the end. At least I think so. Overall this film makes for a very enjoyable viewing experience, in my moderately humble opinion. I also imagine there is more humor to be found in the movie than in the short story, based primarily on Foulger’s performance, but I suppose I could be wrong about that.

Thu 2 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

THEODORE STURGEON – Some of Your Blood. Ballantine 458K, paperback original, 1961. Reprinted several times.

Speaking of tough, fast and scary, following my review of Jim Thompson’s Savage Night, I revisited Theodore Sturgeon’s Some of Your Blood, which has all that and is also by way of being one of the most compassionate books I’ve ever read.

The tale of a bloodsucking freak is told as a psychological detective story, with an overworked Army shrink trying to delve into the psyche of a likable but mysterious GI, “George” whose personal correspondence is the catalyst of the case. Along the way we uncover serial killings and some other things not suitable for a family show, but Sturgeon never loses sympathy for “George” and the result is a uniquely chilling and memorable story.

Thu 2 Jun 2011

Convention Report: CINEVENT 43

by Walter Albert

Bombay Mail was screened at Cinevent in Columbus, this past weekend. I certainly agree with Steve’s assessment of the film, reviewed here, which is fun but cluttered with too much plot and too little development of the large cast of characters. This might, however, repay a visiting, and Steve, I’d be interested in your take on the film after a second viewing.

There were several crime films screened, and, of the ones I saw, I was most impressed by The Under-Cover Man, a 1932 Paramount Publix release, that gave George Raft his first starring role. He had no great range as an actor, but the role, that of a small-time crook who goes undercover for the police to help them catch the murderer of his father, nicely suited his talent. It also helped that he had a strong supporting cast that included Nancy Carroll, Lew Cody, David Landau, Gregory Ratoff and Roscoe Karns.

I was less impressed by a British film, Appointment with Crime (a British National release, 1946), a grim little drama that was marred by a badly written climax that may have been scripted to satisfy a morality code demanding a “suitable†punishment for the criminal lead (Kenneth Harlan). There were some striking performances, most notably that of Herbert Lom as an upperclass villain, standing out among the lowlifes he dealt with.

An oddity was Blondie Has Servant Trouble, an old house mystery in the long-running Columbia series based on the even longer-running newspaper strip. I’ve seen the movie more than once (and I did see it on its original release) and it’s probably the only one of the series that I would watch again.

An enthusiastic Variety review is quoted, and, with even a modicum of encouragement, I will pull the film from my box set of the complete series (now you know the probably awful truth about my taste in films) and see if it’s held up for me.

For the record, the films I most enjoyed at the convention were Dick Turpin (Fox 1925; John G. Blystone, director; starring Tom Mix); The Virginian (B. P. Schulberg Productions, 1923; Tom Forman, director; Kenneth Harlan (The Virginian), Florence Vidor (Molly Woods), Russell Simpson (Trampas), and Pat O’Malley (Steve); and Mare Nostrum (MGM, 1926; Rex Ingram, director; Alice Terry and Antonio Moreno).

I will add that Ellery Queen’s Penthouse Mystery (Darmour Inc./Columbia release, 1941; James Hogan, director, Ralph Bellamy, Margaret Lindsay, Charley Grapewin, and Anna May Wong, among a cast of familiar faces) seemed to me a silly travesty of the EQ character, with Bellamy dithering through much of the film over Nikki Porter’s “meddling†in a murder investigation instead of sticking to her typewriter and working on his latest novel.

After the screening, when a friend asked me what I thought of the film, and I told him, it was only then that he told me that, fired by his enjoyment of the film, he had bought a complete set of the Queen films from one of the convention dealers. Not one of my more comfortable moments during the convention.

Thu 2 Jun 2011

If you’re a fan of Old Time Radio (The Green Hornet, The Shadow, Sam Spade) and Early TV (The Twilight Zone), then you already know Martin Grams’ name. But you may not know that he’s started his own blog: http://www.martingrams.blogspot.com/

So far he’s been posting only once a week, but each post is long and jam-packed with vital information to collectors and connoisseurs of, well, Old Time Radio and Early TV shows, information you will find nowhere else, I guarantee it.

Topics covered so far, working backward:

Boris Karloff: The “Lost” Radio Broadcasts

Cincinnati Old Time Radio Convention

Batman: The TV Series

Cavalcade of America, A History in Pictures

Duffy’s Tavern: Year One

Wed 1 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

ROUND ROBIN MURDERS:

The Floating Admiral (1931) and Double Death (1939)

by Curt J. Evans

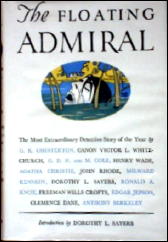

In its ongoing attempt seemingly to wring every last pound of profit out of the Agatha Christie literary estate, HarperCollins has recently reprinted The Floating Admiral, the collaborative detective novel (originally published in 1931) by fourteen members of the then recently formed Detection Club (each writing a successive chapter).

Although Agatha Christie’s contribution is a chapter of eight pages (in my 1979 Gregg Press edition) — 3% of the book — she gets top billing, with only Dorothy L. Sayers and G. K. Chesterton (the latter of whom contributed, by his own admission, a strictly ornamental prologue of five pages) also being mentioned by name, in much smaller letters. Such are the publishing perks of fame and continued books sales!

To my mind, the detective novel, requiring as it does the most scrupulous planning, is not really a form that is receptive to “round robin” treatment. Case in point: The Floating Admiral. Overloaded with complications from too many eager hands, the tale in my opinion begins to take on water and sink well before reaching its conclusion (tellingly entitled by Anthony Berkeley, “Cleaning Up the Mess”).

Nevertheless, if one is interested in authors of Golden Age detective fiction, The Floating Admiral is in many ways quite interesting, whatever its artistic failings.

Things go pretty well for the first five chapters (written by Canon Victor L. Whitechurch, G.D.H. and Margaret Cole, Henry Wade, Agatha Christie and John Rhode), with the authors refraining from over-elaboration. Unfortunately the calmly floating boat is upset by water violently churned by Milward Kennedy (his chapter, which follows Rhode’s “Inspector Rudge Begins to Form a Theory” is impertinently entitled “Inspector Rudge Thinks Better of It” — the good Inspector should not have).

Dorothy L. Sayers tries to straighten everything out that had tangled with a thirty-seven page chapter but she only makes things worse.

Ronald A. Knox’s chapter, “Thirty-Nine Articles of Doubt” (Chapter Eight) warningly raises thirty-nine problematical points that have accumulated for the authors following him to consider and Freeman Wills Crofts in Chapter Nine politely notes that, among other things, the body (allegedly of the admiral of course) was never adequately identified or an inquest arranged. But all to little avail.

Clemence Dane complains in her notes to her Chapter Eleven, the penultimate chapter, that the mystery has become “quite inexplicable to me” — and she likely has not been alone in that sentiment over the years.

Anthony Berkeley’s conclusion has been praised heartily by over-generous critics. I deem more like the curate’ egg — good in spots but essentially rotten. But to be fair to the poor fellow, he was handed the devil of a job.

The fun for me in reading The Floating Admiral is not in reading a cogently plotted detective novel (it simply isn’t one), but in seeing the narrative approach each author takes in his/her chapter:

â— G. K. Chesterton writes rich prose.

â— Canon Whitechurch introduces a charming vicar.

â— Henry Wade develops appealing and credible relationships among his policemen.

â— Out of the blue, Agatha Christie introduces a garrulous, gossipy lady innkeeper.

â— John Rhode discusses tidal movements (the admiral was floating after all) and sympathetically expands the role of the retired petty officer, Neddy Ware.

◠Milward Kennedy overcomplicates the story, as does Dorothy L. Sayers (the ingenious Sayers should have been given the opening chapter — she and Kennedy both clearly wanted it).

â— Ronald A. Knox makes a long list.

â— Freeman Wills Crofts checks alibis and has his inspector travel by train.

â— In his notes to his chapter, Knox amusingly declares, “I once laid it down that no Chinaman should appear in a detective story. I feel inclined to extend the rule so as to apply to residents in China. It appears that Admiral Penistone, Sir W. Denny, Walter Fitzgerald, Ware and Holland are all intimate with China, which seems overdoing it.”

In her recent Guardian review of the new edition of The Floating Admiral, Laura Wilson deems Agatha Christie proposed solution for the tale “as you would expect, the most ingenious” of all the solutions. Certainly it’s more tricksy than, say, the solution proffered by John Rhode (without a complicated murder means, Rhode is unable to play to his greatest strength here). It’s also absolutely absurd.

Here’s how Christie envisioned the state of affairs in the Admiral’s household (*** SPOILER *** to Christie’s proposed solution follows, obviously):

The Admiral’s niece is really his Uncle’s nephew masquerading as the niece. He has been doing this in his Uncle’s household for weeks, and is able to get away with it because he “has been an actor at one time” (that Golden Age crutch for the unlikely accomplishment of great disguises) and because the Admiral has not seen the niece since she was a child (he has seen the nephew more recently, however). The servants are fooled as well, as are the various beaux of the neighborhood, whom the nephew “takes an artistic pleasure” in vamping. (*** END SPOILER ***)

Ingenious or rather ridiculous? You decide for yourself, but I know what I think.

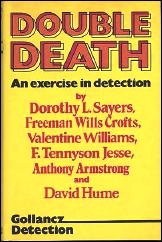

On the whole, I much preferred Double Death, a round robin novel with chapters by Dorothy L. Sayers, Freeman Wills Crofts, Valentine Williams, F. Tennyson Jesse, Anthony Armstrong and David Hume that originally appeared in the Sunday Chronicle in (I believe) 1936 and was published in book form by Victor Gollancz.

It is often stated to be a Detection Club production, but I do not see how this could be, since only two of the six writers, Sayers and Crofts, were members of the Detection Club.

In her introductory chapter to Double Death, Sayers sets up a compelling possible domestic poisoning situation, followed by a death at a railway station, at the evocatively named town of Creepe.

Freeman Wills Crofts embroiders on this opening situation ably (he even provides a stunning map of Creepe and Creepe station), as does Valentine Williams, though the latter is more known for his “Clubfoot” thrillers than his (underrated) detective novels. Unfortunately the later authors are less concerned with cluing, so that as a fair play mystery the tale ends up rather a bust (especially if you read the silly prologue, added later).

However, the writing and overall emotional situation remains compelling throughout Double Death, thus making the tale more of a success than the The Floating Admiral.

It’s interesting to note that in Double Death, written in the mid-thirties, all the authors are concerned with maintaining love interest; whereas in The Floating Admiral all the characters are sticks in whom one could not be expected take the slightest interest (well, there’s the vamping transvestite nephew, as envisioned by Christie).

As the 1930s progressed, the Golden Age detective novel began to put more emphasis on emotional situations and less on ratiocination. In the end, it is this shift in emphasis that makes Double Death more interesting than The Floating Admiral, in my view. Admiral depends for artistic success on detection and too many hands on deck sink the craft.

Yet with less than half the people involved, Double Death might have managed to work as a true fair play detective novel. Certainly Sayers, Crofts and to a lesser extent Valentine Williams made an admirable start of it.

I rather wish the novel could have been kept a collaboration simply of two: Sayers and Crofts. The two authors corresponded over the opening chapter of Double Death in the spring of 1936, with Sayers requesting and Crofts supplying pertinent points of railway station detail.

Sayers had already written her railway timetable novel The Five Red Herrings (1931) as a sort of homage to Crofts’ Sir John Magill’s Last Journey (1930) — these two brilliant books continue to stand today as the ne plus ultra of railway timetable mysteries. Double Death in their hands might well have been a classic product of the Golden Age. As it is, it is still a good read.

Wed 1 Jun 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

MODERN LOVE. Universal, 1929. Charley Chase, Kathryn Crawford, Jean Hersholt, Anita Garvin. Screenplay by Albert DeMond and Beatrice Van. Director: Arch Heath. Shown at Cinecon 44, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2008.

Long considered to be a lost film, but “recovered” by researchers at Universal, this Charley Chase feature was filmed during the transition from silent to sound and includes silent episodes with intertitles, interspersed with some talking sequences.

In this modern comedy of manners, Charley’s young wife (Kathryn Crawford) is forced to keep her marriage a secret to hold on to her job. When a client (Jean Hersholt) arrives from France, Crawford is obliged to give a dinner party, with Charley serving the meal.

This extended sequence is the comic highlight of the film, with Hersholt, unfamiliar with American table manners, willingly following Charley’s lead at using what he imagines to be proper etiquette. The other guests, not wanting to embarrass Hersholt, imitate his bizarre performance to Crawford’s consternation and Charley’s barely concealed delight.

Charley gives a charming performance, nicely supported by Crawford, and if the film lacks the inspired playfulness of his best shorts, it’s still a very entertaining demonstration of Charley’s comic skills.

Another rare Chase film was screened during the weekend, The Awful Goof (Columbia, 1939), the first of four shorts that completed Charley’s contract at Columbia.

This is one of those marital comedies at which Charley excelled, which often consisted of two married couples involved in misunderstandings that put Charley on the receiving end of some unwelcome attentions from a husband who suspects him of playing around with his wife.

This short was, in part, a remake of a classic short, Limousine Love (1928), and not a very successful one. The audience loved the short, while I found it a sad reflection of past glories.

« Previous Page — Next Page »