July 2011

Monthly Archive

Wed 6 Jul 2011

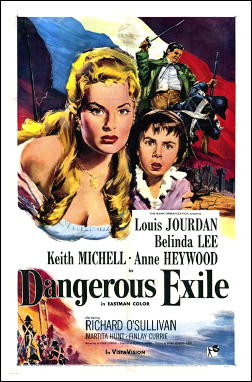

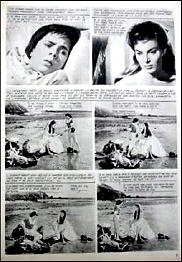

DANGEROUS EXILE. J. Arthur Rank, UK, 1957. Louis Jourdan, Belinda Lee, Keith Michell, Richard O’Sullivan, Martita Hunt, Finlay Currie, Anne Heywood, Brian Rawlinson. Based on the novel A King Reluctant by Vaughan Wilkins. Director: Brian Desmond Hurst.

History, once in a while, rises to the occasion and outpaces and outdates historical fiction, sometimes in flashy fashion and sometimes not. Either way, does the truth always out? We hope so.

Dangerous Exile is a film that takes place at the time of the French Revolution, centering as it does upon ten year old Louis XVII, son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette and the heir to the throne when his parents are beheaded.

In this film he makes his way to a mansion on the coast of Wales in a hot air balloon, a very neat conceit at the time the movie was made. As is known now, this could not have happened. The Dauphin died in a Parisian prison cell, still only a little boy, as verified by DNA tests made not so many years ago.

But let’s go with the fiction. Even if Mars is uninhabitable, the story’s the the thing, as fans of Edgar Rice Burroughs know full well. In Wales the young lad taken in by some British gentry, and to tell you the truth, I like this version of the story better, truth or not.

Louis Jourdan plays a French aristocrat who smuggles the lad out of his home land, leaving his own son behind to play the part in the would-be king’s place, while Belinda Lee, an American visiting her British aunt, is the woman in whose charge the boy is placed.

His life, of course, is much happier there, having witnessed at least the death of his mother, and he soon no longer wishes to be king. Richard O’Sullivan, who plays the young boy to perfection – even the smile-producing scene in which he proposes marriage to the beautifully buxom Miss Lee is done well – later became a fixture on British TV, but to all intents and purposes is totally unknown in this country.

Knowing more about the intrigue that was going on in France at the time will boost your enjoyment of the story as it goes along, and truth be known, this is a failure I find in myself. Even so, if good old-fashioned swordplay is what you are looking for in movies like this, the action toward the end of the film picks up noticeably, and it’s worth waiting for. (And unlike the photos to the left and above, the film is in color.)

Dangerous Exile is a minor film, I admit, but when I happened to watch it, it was exactly what I wanted to see at the time.

Tue 5 Jul 2011

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

T.H.E. CAT. NBC-TV. 26 episodes. 30 minutes. September 16,1966 through March 31, 1967. Created: Harry Julian Fink. Produced: Boris Sagal. Cast: Robert Loggia (Thomas Hewitt Edward Cat), Robert Carricart (Pepe Coroza), R. G. Armstrong (Police Captain McAllister).

In the fifties and sixties, many television series featured a darker hero, a cool intelligent fearless man of action, and a jazz soundtrack to highlight the noir-like visual look of such a man’s world. T.H.E. Cat was among the best of such series.

“Out of the night comes a man who saves lives at the risk of his own. Once, a circus performer, an aerialist who refused the net. Once, a cat burglar, a master among jewel thieves. And now, a professional bodyguard. Primitive. Savage. In love with danger. T.H.E. Cat.” (from NBC introduction that can be seen at YouTube).

Robert Loggia was perfect as T.H.E. Cat. His looks, even the way his body moved, made Loggia the ideal choice for the circus performer turned thief turned bodyguard.

Much of the series reminds one of Peter Gunn, such as the opening titles and “Casa del Gato,” the jazz nightclub Cat owned with his gypsy friend Pepe. Lalo Schifrin’s wonderful jazz music was as valuable to T.H.E. Cat as Henry Mancini’s music was for Gunn. But T.H.E. Cat went beyond Peter Gunn.

Created by Harry Julian Fink, who would later create “Dirty Harry,” T.H.E. Cat was set in a violent world full of odd exotic and often damaged people such as a dethroned King, a psychopath who refused to wear shoes, and Cat’s police contact, the one-handed Captain McAllister.

Talented Boris Sagal set the look for the series as the first episode’s director and series producer. Not surprisingly, among Sagal’s many director credits include episodes of Peter Gunn and Mike Hammer (1958-1959). Another director for this series worthy of note was Jacques Tourneur (Out of the Past) who directed the episode “Ring of Anasis” (December 30, 1966).

The series focused on crime over mystery, action over clues, and style over realism. T.H.E. Cat featured scenes worthy of the Bond-like hero of the time.

In “To Kill a Priest”, Cat faced the killer and his gang in the villain’s own lair, the old Hall of Justice building the villain had bought. Cat threatened the mobster, ignoring the gunmen and their guns pointed a few inches from his head. While of poor quality, this is the only full episode available to view on YouTube. (The link is for Part One of Three.)

Despite being filmed in color, the noirish feel to the series was not totally lost. The damaged characters, jazz music, violent action, creative camera angles and lighting, all made T.H.E. Cat a series worth watching then and now. Hopefully, someday the series will make it to the world of the legit DVD, and we will see it in the remastered quality T.H.E. Cat deserves.

Tue 5 Jul 2011

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

RICHARD SHELDON – Poor Prisoner’s Defense. Simon and Schuster, US, hardcover, 1949. Hardcover reprint: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, 4-in-1 edition, December 1950. First published in the UK: Hutchinson, hardcover, 1949.

Offered the junior brief in a [pro bono] “poor prisoner’s defense,” Dick Rayne can’t afford to turn it down, even though he has no experience in murder trials. Rayne has come late to the law and needs any brief he can get to keep going as a barrister. Even working with an incompetent solicitor is better than nothing.

About a quarter of the novel is taken up by the trial of Rayne’s client for slitting the throat of his alleged paramour. Rayne himself isn’t sure whether he is guilty or not guilty. There is, however, no doubt in the jurors’ minds. A guilty verdict is arrived at, followed by a sentence of death.

Still uncertain about his client’s guilt, Rayne, with the aid of his wife, begins his own investigation, with limited time and even more limited funds. Since apparently no one on trial in a mystery novel is ever guilty of the crime charged — although Jon Breen, the expert in this area, may be aware of exceptions — the reader knows the defendant didn’t do it.

Who, then, did do it? That, too, is no surprise, but getting to the solution with Rayne and his wife is an enjoyable process.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 3, Summer 1990.

Bibliographic Note: Richard Sheldon was the author of one other crime novel, that being Harsh Evidence (Hutchinson, 1950). This later book takes place in England in 1874, according to Hubin, which means that Dick Rayne and his wife never had a second chance to show off their investigative abilities.

[UPDATE] 07-07-11. After some discussion of the author in the comments, centering about the fact that nothing was known about him, Jamie Sturgeon purchased a copy of Sheldon’s second book and was rewarded with not only a photo and but a short biography as well. I’ve created a followup post here to include this and perhaps any additional information that may be found.

Mon 4 Jul 2011

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by MONTE HERRIDGE

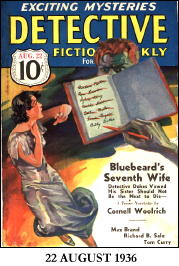

#5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

The Secret Agent George Devrite stories by Tom Curry were a short series of seven stories published in Detective Fiction Weekly from 1936 to 1940.

The series involves the exploits of an undercover policeman, or secret agent, of the New York Police. Inspector Hallihan was his superior in the department, but George Devrite was in essence the Secret Police Chief. He had an obscure office on the second floor of a dingy house “down the street from Headquarters, outwardly an importer of beaded goods but actually the main receiver of reports made by such agents as Devrite.†(The Green Fingers of Death)

These reports often consist of factual accounts of their actions and gives recommendations to Hallihan of what to do – people to investigate, arrest, or otherwise take action about. Devrite “received credit only in the secret records of the Police.†(The Donkey’s Head) He lived in a small apartment in the West Forties, and had no close friends, as his job did not allow such.

As to entertainment, Devrite derived “his main amusement … in solving the puzzles presented by Hallihan.†(The Donkey’s Head) So Devrite could be described as a workaholic who lived for his job.

Devrite usually visited the scene of the murders he investigated in order to gather information. As Devrite puts it when he closes in on some criminals, “with twenty thousand policemen on tap but Devrite dared not call one to assist him directly, since he was an undercoverman and could not expose himself to friend or foe.†(The Green Fingers of Death)

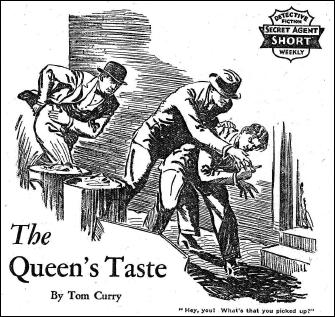

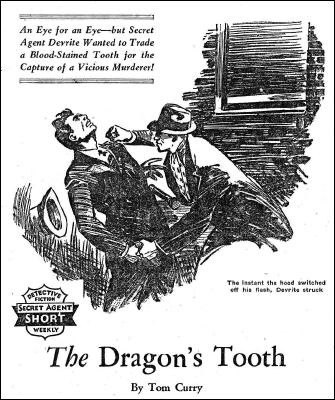

Devrite’s orders at all times was to never expose himself. He did not make arrests or appear in court to give trial testimony. It was explained in the second story in the series (The Queen’s Taste), that “George Devrite was a valuable man – irreplaceable save by years of training; his natural competence and experience made him Hallihan’s star.†Part of Devrite’s training is in ju-jutsu, which he uses in a number of the stories, especially “The Dragon’s Tooth.â€

In the first story in the series, “The Green Fingers of Death,†one of Devrite’s fellow agents has been found murdered, and Hallihan gives the case that he was working on to Devrite to investigate. It involves a young bank clerk named Robert Evans, who is in some sort of trouble.

Devrite does some investigating and finds that Evans owes a gambling debt to a German named Count von Hult. Hult wants something unknown in return for this debt, which turns out to be passing counterfeit money at his bank. Devrite tracks down the counterfeiters and his earlier report to Hallihan set the police on their track too.

The second story in the series, “The Queen’s Taste†involves Devrite in investigating a murder case. The police haven’t been able to solve the case satisfactorily, so Inspector Hallihan puts George Devrite on the case. The police think they know who committed the murder, and Devrite winds up agreeing with them.

The culprit is a Cuban named Luis Ortez, a former triggerman turned dancer at the Peacock Cabaret. His dancing partner is the murdered man’s daughter, Adele Morris. Ortez is interested in Adele Morris, and part of Hallihan’s instructions to Devrite stressed that he was to see what he could do to stop this interest. Devrite runs into the usual danger in this case, barely escaping with his life after gunmen target him.

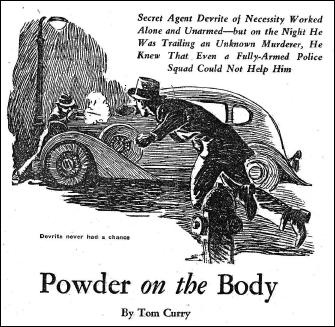

“Powder on the Body†is the third story, and Devrite is assigned to investigate a series of murders after the police come up with a dead end. Each of the victims is well-off, each has talcum powder on his suit, and each has been robbed and shot at close range.

One more victim is killed while Devrite is investigating, making him more determined than ever to solve the case. The victims all went to a night club called the Blue Belle before they were killed, so Devrite starts there. As usual in this series, Devrite comes near death in his attempt to get to the bottom of the murders.

In “The Dragon’s Tooth†Devrite investigates the murder of William Brennan of Brennan and Kanes, furriers. Also he was to track down the $250,000 worth of furs stolen at the same time. Devrite infiltrates the underworld to a slight degree in this one, and gains some information that sets him on the trail of the solution to the crimes.

Not only does Devrite’s work clear up the murder, but it also breaks up a criminal gang of fur thieves and put a number of its members in jail.

“The Visit of Death†involves Devrite in still another murder case, that of Daniel Moresby, rich recluse. The only clue to the murderer is a chunk of lead, which turned out to be a railroad freight car seal. So Devrite puts on some old clothes and goes to the hobo encampment near the railroad tracks, hoping to find further clues and some information. He finds more than he bargained for, as the murderer and a companion show up at the encampment.

“The Donkey’s Head†finds George Devrite investigating another murder, that of Keith Mortimer, a fairly young rich man who lived an idle life. Other than a possible burglar, there are only two suspects in the case so it is a matter of tracking down clues on each suspect.

Devrite has his life saved by one of the suspects, and becomes indebted to him for that to the point where he is temporarily unwilling to investigate further. However, his work ethic convinces him to continue the investigation. The title of the story refers to the murdered man’s broken Chinese vase, which is in a hundred pieces when Devrite and Hallihan see it. However, a small piece showing a donkey’s head is missing from the reconstructed vase and provides a clue to the murder.

“Racket Kill†is the last story in the series, and was published over 2 ½ years after the previous story. Kenneth Harris, a Bronx garage owner, has been murdered racketeer style. Hallihan instructs Devrite to investigate. The only suspects are Harris’ partner, Jerry Sessler, and the local racketeers who peddle stolen auto parts to the garages. Devrite almost immediately gets into trouble with the racketeers, and has to talk fast to get out of it.

This is an average series, with some very good stories, but mostly average or slightly above that. There is no element of humor in the stories, and the hardboiled nature of the stories denies any lightness to them. This series is better than other stand-alone stories about undercover police that was published in DFW.

The Secret Agent George Devrite series by Tom Curry:

The Green Fingers of Death August 22, 1936

The Queen’s Taste August 29, 1936

Lion Face September 5, 1936 [**]

Powder on the Body November 14, 1936

The Dragon’s Tooth November 21, 1936

The Visit of Death December 19, 1936

The Donkey’s Head January 2, 1937

Racket Kill August 31, 1940

[**] This story has been added later, thanks to Ron Smyth who discovered its existence and told us about it in the comments. Not only that, but it can be read online at http://www.unz.org. Follow the link to the website, next to the Detective Fiction Weekly page, then to the issue itself.

Mon 4 Jul 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

LAURIE KING – Grave Talent. Alonzo Hawkins & Casey Martinelli #1. St. Martin’s, hardcover, 1993. Bantam, paperback reprint, 1995.

There are so many first novels appearing now, in both hardcover and paper, that it’s a wonder to me that any of them get bought. How do you choose? I usually don’t, barring a free review copy, but for some reason this caught my attention, and I did.

The ingredients are familiar: crusty old San Francisco homicide detective (Alonzo Hawkins) is assigned a newly promoted female partner (Casey Martinelli) to work on a brutal and sensational child murder, as much for political reasons as anything else.

Then a second and third child are murdered, and all are found to center on a rural colony outside San Francisco. One of the residents of the colony is a famous artist living incognito there, who also happens to have been convicted of and served a sentence for child murder. Too obvious? Maybe, maybe not; certainly many things are not as they seem.

This was an interesting book, and overall a good one. It wasn’t a typical procedural, but neither was it a let’s-get-touchy-feely-with-the-characters-and-to-hell-with-police-reality type.

The story is told mostly from Martinelli’s viewpoint, and really has two main focal points other than the mystery proper: the tortured life of the artist, and the relationship between the detectives.

Martinelli and Hawkin are both complex and interesting characters that I think will bear the weight of a series, though it isn’t clear if there will be one. The writing is quite good. This isn’t one of those books that shouts that a new star is born, but it’s considerably better than the first-novel norm, and I think the lady has a future.

Recommended.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #7, May 1993.

Editorial Comments: Barry was right on the money on two counts. First of all, Grave Talent won the Edgar Award for Best First Mystery in 1994. Barry must have been among the first to read, review and recognize that the book was “considerably better” than most first mysteries.

And yes, Laurie King has had a future, and yes, Grave Talent was the first of a series. (Does that make three counts?) There are five in the series now, the most recent being The Art of Detection (2006).

If anything, though, Laurie King is more well-known for her second series of mystery novels, the one in which Mary Russell meets and befriends Sherlock Holmes at a young age (hers). He becomes her mentor in solving several crimes, then later her partner and companion; in fact, they later marry. There are eleven in this series, the most recent one being Pirate King (2011).

Sun 3 Jul 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 4.1: Themes and Strands (Durbridge Cliffhangers)

While most UK TV viewers surrendered to the spell of the Scotland Yard detective series during the 1950s, another sub-division of the TV genre was attracting something of a mini-following in Britain. The thriller serial.

Once settled into the post-war comfort of its role in British life, BBC Television began to develop the format of drama series and serials in earnest. A television serial template was struck, conforming at first to the nervous frenzy of “live” TV production and then to a uniform house style (the half-hour, six-part format).

When Francis Durbridge emerged in television in 1952 with the six-part thriller serial The Broken Horseshoe, the first of this type of programming, he combined the psychological thriller with the multi-part mystery.

The two notable genre-related forms had first appeared in the autumn of 1951: the single play Night of the Fourth (a detective story with a psychological theme; adapted from the German play Sprechstunde) and C.A. Lejeune’s six-part series of adaptations of Sherlock Holmes stories (presented as a series of self-contained, 35-minute plays). It is interesting that these two elements should form the basic structure of what became in the 1950s (and continued through into the 1960s): the BBC Durbridge mystery-thriller serial.

Durbridge was a radio writer (he had introduced BBC listeners to his amateur sleuth Paul Temple in 1938 [Send for Paul Temple]) whose name on the television credits could be relied upon to raise high hopes.

He treated his themes — murder, smuggling, treachery — with an unsentimental, civilised levity. There was in the writing a blend of the ironic and the ruthless, a switch in mood from amusing bafflement to disturbing seriousness, that was tartly refreshing in itself while requiring the utmost concentration and evenness of style in the direction.

While some type of criminal activity was usually embedded into the narrative (be it race fixing, dope smuggling, kidnap), it was the psychological bewilderment of the hero that was often the focus. The Teckman Biography (1953-54) and Portrait of Alison (1955) both move around characters who are supposedly dead but who mysteriously reappear, alive and informed and involved in a criminal enterprise.

In Melissa (BBC, 1964; remade 1974) it is the “wrong” person who is reported dead. A sense of timeliness was displayed in his Operation Diplomat in late 1952, concerning the mysterious disappearance of a top secret diplomat, and seemed to be perfectly keyed to the 1951 defection to Russia by British intelligence officers Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean (although Durbridge claimed coincidence).

The BBC’s treatment, with its rococo embellishments and general atmosphere of menace thickened by producer-director Martyn C. Webster’s staging in the early days (by producer-director Alan Bromly in later years), was as assured as any TV viewer at that time had a right to expect.

On the other hand some of the subsidiary scenes and characters were, if anything, under-developed. But the serials’ main weakness was the absence of expressive cutting and visual flow. As a result, certain half-way stretches of dialogue became tedious to watch; and the essential awareness of the writer’s shifting tensions yielded disappointingly to the easier mannerisms of any conventional thriller.

The typical Durbridge world of the thriller is comfortably middle class (of the post-war era), breezing with terribly English country-inn-and-gin types, often with the hero a self-sufficient artist or a writer, and always with the inevitable, and dependable, Scotland Yard man on hand when necessary.

Heavily dependant on dialogue and an end-of-episode hook, the serials were often little more than televised radio scripts, but this was to the serials’ advantage in the early days. In the Durbridge universe, everyone is tainted with a suggestion of menace or deceit. Absolutely no one is to be taken on face value. Information is deliberately withheld from the viewer, as well as the hero, almost to a point of irritation.

These complicated, intellectual crime riddles tended to overshadow his clearly stock characters (always in search of that elusive depth), somehow making him the ingenious master of the television mystery serial for almost two decades, until the times changed and the old-fashioned formula evaporated.

It wasn’t long before the UK TV schedules were thick with mystery-thriller serials, all designed and delivered in the Durbridge mould. Author Michael Gilbert studied the Durbridge form and wrote the underworld thriller The Crime of the Century (BBC, 1956-57); screenwriter Jimmy Sangster turned in the murder mystery Motive for Murder (ITV, 1957), and The Assassin (ITV, 1958), involving the hunt for a killer-for-hire; and Anthony Berkeley’s 1937 novel Trial and Error, about a murderer setting out to prove the innocence of a wrongly accused man, was adapted as the six-part Leave It To Todhunter (BBC, 1958).

Rival channel ITV’s serial master was Lewis Greifer, a prolific radio and TV writer whose work in the serial format (in collaboration with producer-director Quentin Lawrence) was not too far removed from the Durbridge world of psychological terrors. The hero faces an identity crisis in the murder mysteries Five Names for Johnny and Web, both 1957; and in The Man Who Finally Died (1959) is confronted with the return of a “dead” man, leading to a convoluted Durbridge-style unravelling of the past.

Astute enough to notice the secret agent genre forming on television by the beginning of the 1960s (with the growing popularity of ITV’s Danger Man; the 1960-62 half-hour series), Durbridge created the lengthy serial The World of Tim Frazer (BBC, 1960-61) featuring a working-class engineer who is recruited by a shadowy government department into acting as an undercover agent.

The unprecedented 18-part serial was surprisingly well-received and even heralded as the successor to the still-popular (via radio) Paul Temple. The detached and skeptical Frazer (performed by a brooding Jack Hedley with insolent confidence) was essentially an outside observer of events who had licence to move through the well-heeled Durbridge milieu with barely-concealed contempt of what was by now stock 1950s British types.

The peculiar success of Tim Frazer continued Durbridge’s celebrity as the master craftsman of the British thriller serial (other contemporary thriller serials were gauged on their ability to render the “Durbridge touch”; Lynda La Plante would receive similar genre worship during the 1980s).

Whether he was blinded by the celebrity or simply coerced by BBC producers hungry for more of the same, Durbridge pressed ahead into the following decades (up until his last serial, Breakaway, in 1980) by giving the viewer (and the producer) more of what he thought they wanted: long, drawn-out, unnecessarily complicated plots populated by thinly developed 1950s-type characters, leading up as always to a sudden surprise revelation in the final episode.

In a television-viewing age that had already experienced by this time a post-Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78) world of stark social realism (explicit violence, police corruption, race conflict, etc.), Durbridge proceeded, seemingly quite oblivious of events around him, to turn out facsimiles of his 1950s plots.

What was at one time the electrifying anticipation of the coming of “another Durbridge thriller” in the 1950s and 1960s had developed by the 1970s into a non-event of bafflement and disappointment.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas).

Sun 3 Jul 2011

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

MARK DE CASTRIQUE – Fatal Undertaking. Poisoned Pen Press, hardcover/trade paperback, October 2010.

Genre: Police Procedural. Leading character: Barry Clayton (5th in series). Setting: North Carolina.

First Sentence: “You want to borrow a casket?”

Deputy Sheriff Barry Clayton, had been a city police officer but moved back to Gainesboro, a small town in North Carolina in which his family runs a funeral parlor.

Working for the sheriff’s department and helping with the family business can lead to interesting situations such as loaning a casket to the Jaycees for a Halloween haunted house and having it end up with a murdered body inside. Complicating Barry’s case is the question whether the victim was the one actually intended and having his reporter ex-wife return to town.

It is always a pleasure to read a new book by Mark de Castrique. He brings us into this small North Carolina town, not so much by detailed descriptions of the environs, but by conveying the closeness of the town’s citizens and with the reality of the town’s politics and insularity.

His dialogue is excellent, including humor — “As he left the diner, I saw the press corps following after him like a gaggle of geese, honking “Sheriff” with every step.” and the use of colloquialisms — “In here we’re two size-ten shoes in a size-four shoebox.” — add contrast to the serious elements of the plot.

The characters are representative of all those you find in any town, but are far from being stereotypical. Sheriff Tommy Lee Wadkins is a man who has seen too much violence and knows you have to have humor, particularly when situations may be serious, to survive.

Barry is dedicated to his family, loyal to his friends, but he’s not perfect. He makes costly mistakes during the investigation and realizes the impact of them. That makes him more realistic than the usual ‘perfect’ detective.

The story draws you in from its seemingly light beginning but turns quickly to dark with the first murder. Yes, first; there is more than one murder, but the story is neither noir nor serial killer in approach. Instead, it is a very well done police procedural.

The plot is full of twists, interspersed with humor, suspense, and tragedy; with a shocking climax and affirming ending; as is life. That is one of the appeals of de Castrique’s writing to me; they are a reminder that life is filled with twists and tragedy, yet also with hope and that it is important to always remember that which is most important

I was happy to read that de Castrique has many more investigations in mind for Barry. I look forward to reading each one of them.

Rating: Good Plus.

The Buryin’ Barry mystery series —

1. Dangerous Undertaking (2003)

2. Grave Undertaking (2004)

3. Foolish Undertaking (2006)

4. Final Undertaking (2007)

5. Fatal Undertaking (2010)

Sat 2 Jul 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

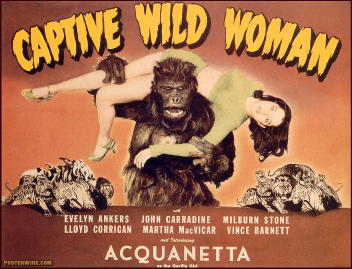

â— CAPTIVE WILD WOMAN. Universal, 1943. Acquanetta, John Carradine, Evelyn Ankers, Milburn Stone, Lloyd Corrigan. Director: Edward Dmytryk.

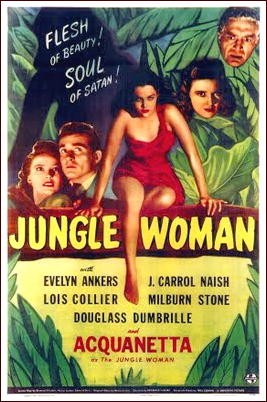

â— JUNGLE WOMAN. Universal, 1944. Acquanetta, Evelyn Ankers, J. Carrol Naish, Samuel S. Hinds, Lois Collier, Milburn Stone, Douglass Dumbrille. Director: Reginald Le Borg.

â— JUNGLE CAPTIVE. Universal, 1945. Otto Kruger, Vicky Lane, Amelita Ward, Phil Brown, Jerome Cowan, Rondo Hatton. Story & screenplay: Dwight V. Babcock. Director: Harold Young.

Among movie studios, Universal is fondly remembered for classic horror films like Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolfman and the sequels they spawned, but the studio put out a good number of lesser efforts, and even a few second-string series, haunted by bush-league monsters who somehow never hit the big time.

One recalls (not fondly) the Spider Woman and the Creeper, both spawned by the superior Sherlock Holmes series, and both duller than dishwater. But perhaps the most persistent of the minor monsters was Paula the Ape Woman.

Captive Wild Woman (1943) initiated the series and it opens with a credit thanking Clyde Beatty for his “inimitable talent and contribution to this film.” Said contribution consists of stock footage from an old circus serial, and why they refer to Beatty as “inimitable” I don’t know, because Milburn Stone imits him all through the movie, as a lion tamer whose every foray into the cage becomes a long-shot of the back of Beatty in the earlier film.

In defense of Milburn Stone, who became a respected character actor on Gunsmoke, I have to say that he puts in a very convincing performance when called on to play Beatty’s back, and it’s only when he goes through the tame leading-man motions that interest flags.

Unfortunately, there’s rather much of this, as the plot of Captive Wild Woman meanders its way from a circus milieu to the den of a mad scientist (John Carradine) experimenting on the sister (Martha Vickers) of leading lady Evelyn Ankers, who put up with quite a lot of that in those days.

Carradine extends his research so far as to steal a gorilla from the circus and turn it into a near-human woman (Acquanetta, “the Venezuelan Volcano”) using glandular injections from Vickers, whereupon the writers decide to get silly and have Carradine take Paula the Ape Woman back to the circus, where she promptly falls in love with Stone and becomes part of his act.

But Stone is already engaged to Ankers, and when Paula gets jealous she morphs into a half-ape and must return to Carradine who is eager to extend his research even further, resulting in a four-sided triangle reminiscent of the lovers in Midsummer’s Night Dream, but without the class.

All this is handled with some amount of style by Edward Dmytryk, a director going places (like Murder, My Sweet and The Caine Mutiny) who throws in the occasional camera angle or bit of moody lighting, but to little effect; Captive struts and frets its brief 60 minutes on the screen, signifying very little indeed.

But any movie with a title like that was bound to draw customers, and returns on Captive were strong enough for Universal execs to order a sequel. Thus Jungle Woman appeared the next year.

This is a strange one, even by B-movie standards, as if, pressed for time, producer Ben Pivar decided to simply re-run the fist movie. About a third of Jungle Woman is lifted bodily from Captive Wild Woman, as stars Milburn Stone and Evelyn Ankers reprise their roles from the first film in a framing device centered around testimony at an inquest involving another mad scientist (J. Carroll Naish this time) and a dead ape-woman (Acquanetta again) found on the grounds of his sanitarium.

Said framing takes up the whole first part of the Jungle Woman, with Ankers and Stone recalling events in flashback from the earlier film, which appear in no particular order, making this thing look like a Resnais film, as the past rises to feebly haunt the present with little coherence or cohesion.

Finally, re-runs exhausted, a new cast appears, and they proceed to tell a story in flashback (did some of this anticipate film noir?) filling out the running time with an account of how Naish, visiting the circus sometime during the first film, was impressed enough to acquire the body of the ape woman, revive her, and start a movie of his own, leading to the unpleasantness that awaits those who dabble in things man wasn’t meant to etc, etc..

Well, sixty minutes pass in this manner, leading to a wrap-up that would have been fairly shocking, had anyone been paying attention. As it is, the final scene gets tossed off like the rest of the movie, and I, for one, was left wondering what they must have been thinking of when they committed this crime against Cinema.

Somehow, though, Universal thought the concept was worth another try, and the next year saw the release of Jungle Captive. This is marginally better than Jungle Woman, and if you look up the term “faint praise” in the Dictionary, you may find the words “marginally better than Jungle Woman.”

Actually, Captive benefits from the appearance of Otto Kruger as this year’s Mad Scientist, who begins by electronically reviving dead rabbits and, with the reasoning of his ilk, decides the next logical step is to steal the body of the Ape Woman from the morgue and revive that.

Kruger handles all this with commendable restraint, and somehow puts Real Feeling into lines like “I need your blood,” though things get a bit much when he decides his ape woman (played by Vicky Lane this time) needs a new brain and proceeds to check out his predecessor’s brain-transplant instructions (written on a 5×8 note card) and borrow a book titled Brain Surgery!

Maybe because it eschews the flashbacks, Captive seems to move at a faster pace, with some creepy support from Rondo Hatton as “Moloch the Brute” and effective makeup for the ape woman.

There’s also an appearance by Jerome Cowan (of whom more later) playing his usual clueless role as a detective, and Vicky Lane, though she gets no lines and has little to do, is a distinct improvement as the new Ape Woman: her strong features and large, expressive eyes remind one of the girls in drawings by Gene Bilbrew, and make me wonder what sort of career she might have made for herself with better luck than this.

Sat 2 Jul 2011

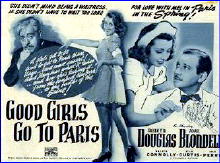

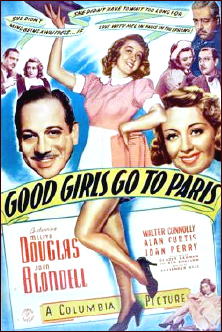

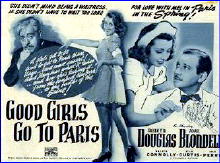

GOOD GIRLS GO TO PARIS. Columbia Pictures, 1939. Melvyn Douglas, Joan Blondell, Walter Connolly, Alan Curtis, Joan Perry, Isabel Jeans. Director: Alexander Hall.

A decent screwball type of comedy, one with a complicated plot, relatively speaking, and one that’s actually quite funny. Not of the side-splitting slapstick variety, but one that’s amusing all the way through.

Melvyn Douglas plays a tweedy sort of visiting professor from England who befriends a waitress (Joan Blondell) who works at a hamburger joint close to campus.

Her goal in life: to coerce a male student with a rich father who objects to their friendship to pay up with a trip to Paris. Blackmail? Yes, and Professor Brooke (that’s Douglas) tries his best to make her see the error of her ways.

But here’s where a “flutter†somewhere inside her helps. That’s her conscience talking.

And here’s where it gets complicated. Brooke’s future brother-in-law is Jenny Swanson’s next target, and somehow she works her way into his home (and Brooke’s fiancée) before Brooke himself gets there before the wedding – mostly by ingratiating herself with the patriarch of the upscale Brand family, played with the utmost gusto by Walter Connolly, who’d rather be back home in Minnesota than in New York City and having to deal with the pair of spoiled socialites he has as children.

It is difficult to say exactly how this not very unique storyline leads itself to humor, but it does. Both Melvyn Douglas and especially Joan Blondell lend their physical talents to the proceedings as well as using their lines to good advantage, acting and reacting.

That Melvyn Douglas and Joan Blondell end up with other may come as a surprise to perhaps one or two viewers of this film, but it will be obvious to everyone else within the first five minutes. Nonetheless it is touch and go for them for a good long time.

[UPDATE] Later the same day. As perhaps even intermittent readers of this blog will recall, Douglas and Blondell also appeared together in There’s Always a Woman. It came out the year before (1938), and I reviewed it here.

But I watched this one first, wrote this review, and forgot to post it until now. (This was back in April when I was having problems with my hip.) I thought the earlier film was a little too mean-spirited, but it was obviously the story and not the two co-stars, since (as you’ve just read) I found this one to be exactly what screwball comedies are supposed to be: a little wacky and fun to watch.

Having also now read the comments on both movies posted on IMDB, there is also the possibility that I am out of step with (almost) everyone else. As the old saying goes, “Humor is a funny thing.”

And, for whatever it’s worth, a note on IMDB says “Originally titled Good Girls Go To Paris, Too, but the censors objected.” Hmm. You’ll have to think about that one — but not too long.

Fri 1 Jul 2011

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

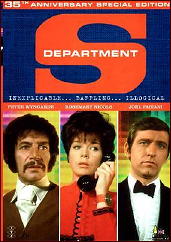

DEPARTMENT S. Syndicated in United States. ITC Production. 28 episodes. 60 minutes. 1969 through 1970. Created by Monty Berman and Dennis Spooner. Executive Story Consultant: Dennis Spooner. Produced by Monty Berman. Creative Consultant: Cyril Frankel. Musical Director: Edwin Astley. Cast: Peter Wyngarde (Jason King), Joel Fabiani (Stewart Sullivan), Rosemary Nicols (Annabelle Hurst), Dennis Alaba Peters (Curtis Seretse). Available on DVD but not in Region One format for the US.

In the 1960s the Beatles were not the only British to invade American pop culture. “Mod” fashions from London and the British TV and Film spies quickly followed. James Bond led the way, followed by The Avengers and a group of ITC-produced TV spies/detectives such as those in Department S. * (See FOOTNOTE.)

Department S was a small branch of Interpol made up of four people dedicated to solving the unsolvable crime. Or to quote a BBC2 introduction to the series (available on YouTube as “Department S: The Gen”), “If its too hot for the cops, a might complicated for the military, call Department S.”

Jason King was a flamboyant, best selling mystery writer who had a love for women and liquor. His fictional detective Mark Caine was in a series of books with such titles as Don’t Look Now But Your Clutch Is Slipping. King would often use Caine’s intuitive methods to help solve the mysteries facing Department S.

Jason King was played by Shakespearian actor, Peter Wyngarde, who Sir John Gielgud said was England’s most underrated actor. Wyngarde was a fan favorite, especially with women. The popularity of Wyngarde’s Jason King would lead to the character getting his own series in 1971.

Stewart Sullivan was the team’s field leader. A man of action, his methods were more procedural such as questioning the suspects.

Annabel Hurst was the beautiful computer scientist whose beliefs in the scientific method of crime solving often put her in conflict with Jason’s more human deductions. Her clothes, what little she wore, were the latest in 1960s fashion.

Curtis Seretse was the bureaucrat in charge of Department S. According to the BFI website Screenonline, the use of a black actor for the part was “a bold piece of casting for its time.”

The four characters set up the ultimate conflict of mystery’s solving methods, with one method always successful in explaining the strangest twist.

Department S shared some characteristics with the more popular and famous The Avengers. Both featured the wild fashion of 60s London and highly stylized writing and direction. Most obviously, both series had a fondness for over the top bizarre plots.

In the first episode, “Six Days” (written by Gerald Kelsey and directed by Cyril Frankel), a commercial plane arrives at a London airport with all on board believing they are thirty minutes early, when they are really six days late. This episode can (for now) be seen on YouTube and is highly recommended. (The link will take you to Part 1 of 4.)

While still fun to watch, the cult favorite has its flaws. There were the typical television mystery annoyances such as a chase because no one thought to guard the exits. But the biggest problem for the modern viewer is what the viewers at the time enjoyed most, the now camp character of Jason King.

FOOTNOTE: The ITC series was made for the American television market, even using the American commercial format and length. It might have appeared in the U.S. first. This would explain why IMDb and BFI have different air dates for the series.

IMDb has the series lasting two seasons. Season One lasted eight episodes from March 9, 1969 through April 27, 1969. Season Two lasted twenty episodes from October 1, 1969 through March 24, 1970. BFI has the series lasting two seasons but starting September 3, 1969 and ending April 3, 1970.

« Previous Page — Next Page »